A Tower to Reach Heaven

Thoughts on the myth of the ziggurat of Babel, from the Bible to Ted Chiang 🛕

Hi!

Welcome to issue number 12 of Light Gray Matters. Let me start by pointing out how happy I am that you are reading this! The newsletter experiment is going well, and that’s thanks to this nucleus of a few dozen readers of which you are a part. Please don’t hesitate to let me know if you enjoy my writing!

And also let others know:

And subscribe if you’re new here!

All right. Enough of this self-promotion, we have serious matters to discuss:

The Tower of Babel.

Behold:

The Tower of Babel by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1563), and counterfeited by me (2021)

You probably know the myth of the tower of Babel from the Bible. It’s actually one of the many tiny subplots in the Book of Genesis. It’s quite short, as Bible stories go (but feel free to skip it):

And the whole earth was of one language, and of one speech.

And it came to pass, as they journeyed from the east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar; and they dwelt there.

And they said one to another, Go to, let us make brick, and burn them throughly.

And they had brick for stone, and slime had they for morter.

And they said, Go to, let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.

And the LORD came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of men builded.

And the LORD said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do.

Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech.

So the LORD scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth: and they left off to build the city.

Therefore is the name of it called Babel; because the LORD did there confound the language of all the earth: and from thence did the LORD scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth.

(Bullet points added to the King James Version by me for readability)

The myth, of course, is known primarily as the reason for the multiplicity of languages.

Humanity, united in a common language and speech, was able to communicate too effectively for the LORD to handle, so the LORD made them unable to talk to each other. Presumably, then, the humans split into many cultures and spent a lot of time fighting one another instead of trying to reach the vault of heaven. The LORD probably saw that it was good.

(I hope I’m not offending anyone whose spirituality is based on the Old Testament. I’m just having a lot of fun writing out the LORD in capital letters every time.)

The tower of Babel story has always felt like a lousy myth to me. Like, surely there were easier ways for the LORD to prevent the construction of the tower. He could have just stuck it down with lightning or something. Language multiplication was probably a fun experiment for the LORD, but fast forward a few millennia and the children of men have figured out how to learn each other’s languages, cooperate, and send rockets into space.

Not a foolproof plan, clearly.

Which is why I like Ted Chiang’s totally different interpretation in his short story Tower of Babylon, published in 1990.

For beholding purposes, here’s the cover of the French edition of Chiang’s first collection:

Tower of Babylon is science fiction, but set in the far past, and in a world unlike our own. In the universe of the story — which is based on ancient Hebrew cosmology — the Earth is flat and covered by the vault of heaven, basically a big slab of white granite. Over the course of centuries, the men of Shinar build a tower to reach the vault.

And reach it they do. It takes months for the miners to climb the tower, and then years to mine the vault of heaven until they find some very strange truth about how the world works.

There is no divine intervention in Chiang’s story. The characters talk about Yahweh all the time, but Yahweh must be less worried than the LORD in Genesis. He just lets them build their tower. No messing around with languages occurs.

This is, after all, a science fiction story. The world has consistent rules, and the characters explore it using physics and engineering, not magic and religion.

Last Sunday, I hosted an Interintellect Book Club Salon to discuss two Ted Chiang stories, including Tower of Babylon. It was fun, and allowed me to appreciate interpretations of the story that I hadn’t thought clearly about until then.

The tower in the story is an awe-inspiring feat of engineering. It is, in many ways, the ancient Mesopotamian equivalent of space travel. Climbing it takes months; so would a trip to Mars. People live in the tower, adapting to life in unusual conditions, never going back to the surface, just like people an a starship leaving the solar system. The tower goes higher than the moon and sun (this is, after all, ancient Hebrew cosmology). And the miners eventually reach the vault, which is a very alien place — much like a foreign planet.

But more interesting is what this tells us about our quest for truth.

At the Salon, we discussed how the process is often more important than the result. If you’re a scientist, it may look like the most important thing is whatever new truth about the Universe you expect to find. But to some extent, isn’t doing the science the important thing? You have to have fun doing it. Or to find purpose in it. If you figured out everything in your field, would you be happy?

And what do you do once you discover a new, strange truth? At the end of the story, the protagonist (who goes by the lovely name of Hillalum) has learned the true shape of the world, and wants to tell people. Chiang does not say how people react. I expect it would be met with disbelief, if not outright hostility, Galileo-style.

The question also arises at the personal level. Imagine you’ve spent a good deal of your life looking for answers, and were lucky enough to find some. Your worldview is changed. Then what? Do you just… go back to live your normal life?

In the end, I wonder if Tower of Babylon is, like the Bible story, a cautionary tale.

Not on displeasing the LORD and suddenly speaking a Finno-Ugric dialect while your best friend now only knows Tagalog.

But on how even if we do reach the heavens and find answers to our questions, we may not know what to do with them. On how we have to love the quest for truth as much, if not more, as truth itself.

With that, I remain

Beholdingly yours,

Étienne

Salon: A Multitude of Tongues

Writing about the tower of Babel today was very relevant, because I’m planning an Interintellect Salon on language diversity. It should be on February 19th. Details soon!

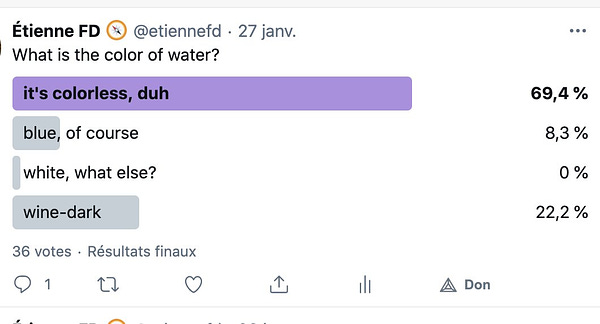

On Twitter: The Color of Water

Do you know the true color of water? I wrote a thread about that the other day. (Hint: most people were wrong)

And here is the less serious companion thread about water molecules doing what they do best, i.e. cheerleading. Enjoy!