All Slopes Are Slippery, Also None of Them Are Actually Slopes

Society as a vast expanse of ice 🏂

Suppose your government is considering legalizing recreational usage of some mild drug like cannabis. You’re against it for whatever reason, and you feel a compulsion to argue online, so you browse to your social media platform of choice and write, “What’s next? Are they going to legalize cocaine? Heroin? Selling fentanyl in government-run stores? Will the government start sponsoring opium dens where a lot of the population will just go waste away their lives while the elite accumulates wealth and power? Is this the first step towards a disgusting future where everyone is wireheaded to a system that delivers feel good chemicals to their brains 24/7????”

This is what’s called a slippery slope argument. It’s generally considered to be a fallacy. Your opponents will probably rush to tell you that much. They’ll point out that legalizing cannabis is qualitatively very different from legalizing hard drugs or opium dens. Such things don’t necessarily logically follow one another.

But also, they kinda do, right? A world where cannabis is illegal while heroin is accepted seems more improbable than one where both are legal. So if you do legalize one, you’re one step closer to legalizing the other. That doesn’t mean it’s definitely going to happen, but it’s somewhat more likely, since a prerequisite has been met. Besides, some of the people who enjoyed being activists for cannabis might be in need of fighting for another cause, and since they’re skilled at arguing for drug legalization, they might pick opium dens as their next thing, bringing momentum to the next stage of the slope.

From there comes a sentiment I’ve been seeing more and more online, which goes, “Slippery slopes may be a fallacy, and yet so far all warnings based on slippery slopes have come true.”

For instance, social conservatives point out that legalizing same-sex marriage seems to have brought us to questioning all sorts of other issues about transgenderism, polyamory, and any number of other sex-related things that they feel are obviously degenerate. (We aren’t at the stage where people marry animals and inanimate objects, and that still feels incredibly unlikely to happen, but is it more likely than it used to be? I guess so!) Meanwhile, progressives who feared that free broad speech norms would lead to the proliferation of harmful extreme ideas seem to be vindicated.

“All slippery slopes arguments are true” is definitely a hyperbole. But I think “all slopes are slippery” is broadly correct. When you apply a force on society in some direction, you always at least risk pushing it farther than you wanted.

Yet I still believe that slippery slope arguments are virtually always fallacies. Not because they aren’t slippery, which they are. But because they aren’t actually slopes.

I live in a country that has already legalized cannabis. Imagine that a political party said they planned to ban it again. Pro-cannabis people could go on their social media platform of choice and write, “What’s next? Are they going to ban cigarettes and alcohol, too? What about sugary foods? Is having fun going to become illegal? Are we going to be monitored by the government 24/7 to make sure we never consume any harmful substance that would impose undue costs on the healthcare system????”

As you surely immediately notice, this is the same slope as the opium den & wireheading one above, except in the reverse direction. (Hopefully I managed to make them both sound equally plausible, but that doesn’t matter too much, since slippery slope arguments are always a bit exaggerated.)

The reason that slippery slope arguments are a fallacy is that we’re always on multiple slopes at once, including exactly opposite ones. If you legalize same-sex marriage, or absolute free speech, or interracial marriage, or drugs, or euthanasia, you might eventually get social change you didn’t want, sure; but if you ban or keep banning any of these things, you might also get social change you didn’t want. Gravity is pulling down and up at the same time.

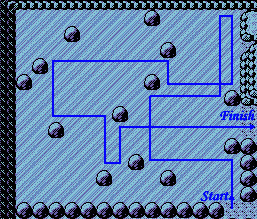

So in reality, the slippery slope metaphor isn’t particularly accurate. It’s more of a flat expanse of ice, like those of the 17th-century Dutch painter Hendrick Avercamp. Everything is slippery, everywhere. Any movement risks bringing you somewhere you didn’t expect to or want to.

The only way not to slip on a flat expanse of ice is to stay put. But in a changing world, where the exact landscape on the ice isn’t static, that’s also a choice that can have slippery consequences, and therefore isn’t necessarily a good strategy either.

It’s fine, I think, to use slippery slope arguments in mature, rational debates. It’s good to warn of the far-reaching consequences some social change may cause. But you have to be prepared for opponents to also bring up the far-reaching consequences of not performing that change, or of performing the opposite change. Most of the time, it will all cancel out, and then we can move on to other, more interesting arguments.

Good one!

saving this article to use as argument