Don't Spend Your Life Building Rube Goldberg Machines

AWM #61: On careers, solving the metaproblem, and fallow periods 🌷

“What do you want to be when you grow up?”

You’re 10 years old, and your teacher or aunt or kind elderly neighbor looks at you expectantly. You struggle to find an answer. You know you could answer “doctor” or “astronaut,” but you’re a smart enough 10-year-old to know that these are stereotypes, that there are countless other jobs out there that you have no idea exist, or even jobs that don’t exist yet. How can you decide now what you’ll be when you grow up?

“A botanist,” you randomly say. You like plants. That’ll do.

“What do you want to study?”

You’re 17 years old and you must pick. Right now it’s mostly a choice between hard science and the humanities, or perhaps some of the more niche options (music, visual arts), but soon you know you’ll have to choose something more specific. Something that you find interesting but also leads to good jobs.

You have good grades in math and science, so your school’s career counsellor tells you that you should pick the hard sciences. Many more opportunities that way. So that’s what you do.

“What kind of jobs are you going to apply for?”

You’re 22 years old and you’re graduating soon. You’re lucky: your major is one of the good ones, one that actually leads to employment and a real career. Some of your friends, who studied underwater basket-weaving, are in a tougher spot.

Still, that doesn’t solve everything. You need to pick companies to work for, do some networking, write cover letters. It’s not going to be fun, but you’ll do it. In a few months, you’ll end up with a nice office somewhere, hopefully working for a good boss, contributing to society. You’ll get a bimonthly salary, which you can use to buy a house, have kids, save up for retirement.

You’ll be set.

Here’s one question that nobody in my story ever asked: “What problems do you think you should try to solve?”

Abstractly, any work can be defined as a problem-solving effort. You might solve the problem of bringing food to people’s plates. The problem of healing somebody’s illness. The problem of entertaining people, of advancing scientific knowledge, of building a new software tool to solve somebody else’s problems.

This is obvious, especially at the micro level. Your daily tasks are going to be dealing with various problems that your boss or clients throw at you.

At the macro level, it is somewhat less obvious. When we consider an entire career, we don’t see it as a large-scale, coherent problem-solving effort. We see it as a “job,” or as a succession of jobs. Or, if you’re more entrepreneurial, as a “business.” We see a university education not as a way to get better at solving certain problems, but as a “degree,” as some obligatory step on the way to your job or business.

As a result, we spend very little time thinking about which problems we want to solve. Actually, let’s unpack that. We spend little time thinking about which problems:

we are able to solve (or able to become able to solve);

we would be good at solving;

we would enjoy solving;

are worth solving at all.

These are not easy questions. For instance, it’s common to be mistaken about our own abilities or what we actually like doing.

It’s also not straightforward to decide which problems are worthwhile. In his advice to would-be startup founders, Paul Graham warns: “By far the most common mistake startups make is to solve problems no one has.” This generalizes. The problems you solve in your current job, are they real problems? Are they more important than some other problems you could be solving instead?

Determining what problem you should be solving with your career is, in itself, a big problem. My friend Daniel Golliher calls this the metaproblem.

Arguably, solving the metaproblem is the most important thing you could be doing in your life. Too bad almost nobody makes a real effort at it.

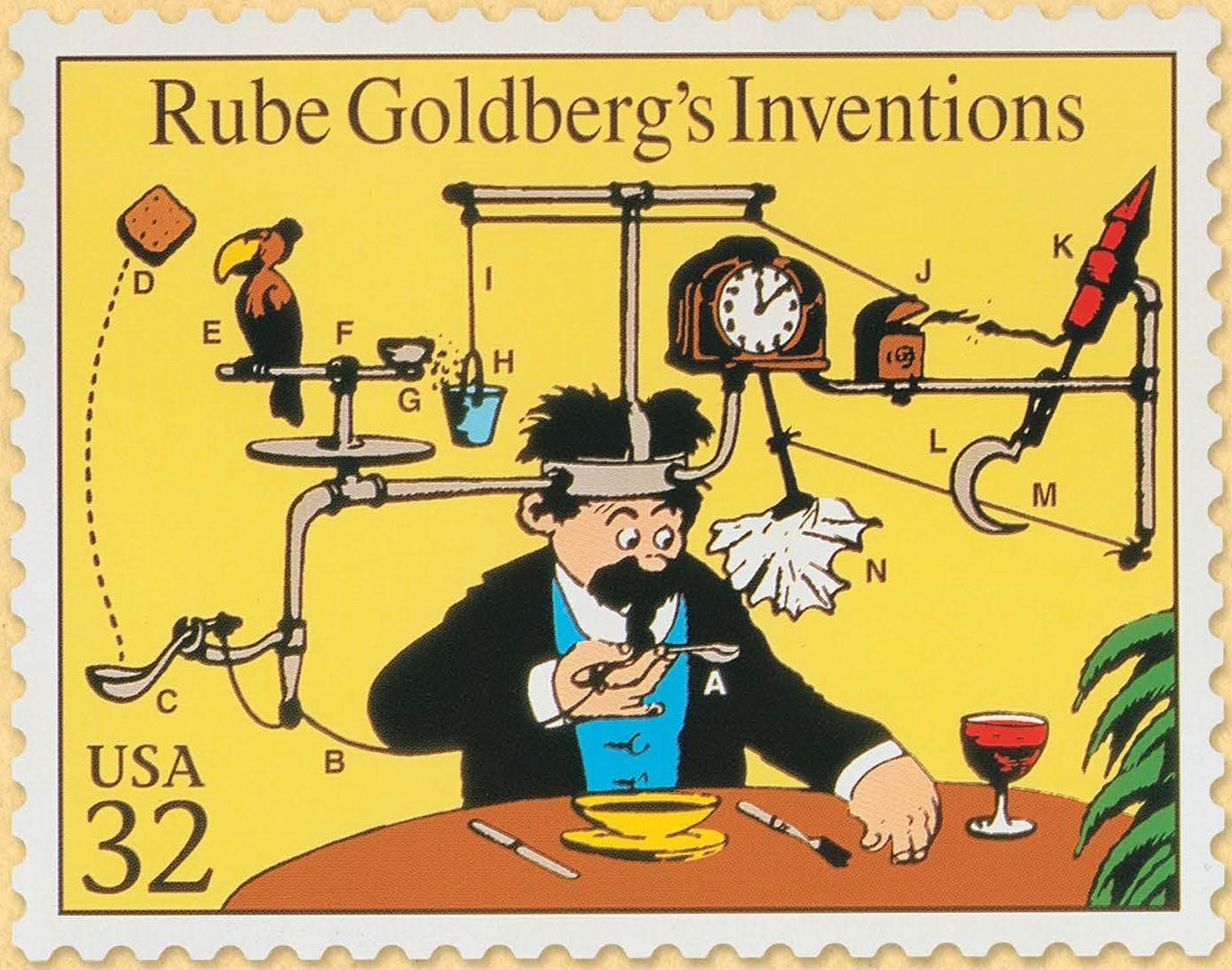

A Rube Goldberg machine, named after cartoonist Rube Goldberg, is a complicated contraption meant to solve a problem in an exaggeratedly inefficient manner.

Exhibit A, the self-operating napkin:

Exhibit B, the soap fetcher:

(For more exhibits by Mr. Goldberg, this page.)

There’s something fun about Rube Goldberg machines. They’re silly, but they’re also amazing displays of creativity. There even exist Rube Goldberg machine contests!

Despite the fun, though, no one is fooled: Rube Goldberg machines are utterly pointless. They solve a problem, but at the cost of incredible complexity that in all likelihood produces even more problems. (How are you going to feed that parrot? Repair whichever flimsy lever breaks? Reset the machine so it can fetch the soap more than once?)

Imagine that some rich person came to you and offered you a very good salary so that you can devote your life to building Rube Goldberg machines. Would you do it? You would essentially be paid to achieve nothing of importance and create new problems along the way. It could be fun for a bit, I guess, but if it were me, I would eventually start questioning my job. Why am I doing this? What purpose does it serve? The people who participate in Rube Goldberg machine contests, presumably (hopefully), become e.g. engineers who then go on to solve real problems; they don’t keep building pointless machines forever.

What machines will you build with your life? This is the essence of the metaproblem. But it goes beyond this, because the metaproblem cannot be left unsolved. You can’t not live your life. Therefore, if you don’t make a conscious effort to solve it, then somebody else will solve it for you. Most likely that means a solution that is tailored to them, not to you.

For most people, this is what happens when they accept a job. A job means being paid to work on somebody else’s problems.

If you’re lucky, those problems are real, and you believe that solving them is important, and it’s all fine. If you’re less lucky, you don’t care about the problems you solve; they’re truly somebody else’s, and over time this will grind you down. It will feel like building a Rube Goldberg machine, because it’s not something that you care about.

If you’re even more unlucky, then you’ll actually be making a Rune Goldberg machine, even if your boss doesn’t call it that. Your job will be a bullshit job: something pointless, that doesn’t really help anyone in the world, or does so in such an inefficient way that it creates as many problems as it solves.

If you get the worst possible kind of luck, then your job might even actively make the world a poorer place, as for instance do weapon researchers, patent trolls, and certain tax optimization lawyers.

You can avoid the worst outcomes — the bullshit jobs and the harmful jobs. But that requires doing some solid work on your metaproblem. Otherwise you’re leaving it up to other people, and who knows what will happen then.

A recent essay by Wolf Tivy, the editor-in-chief of Palladium Magazine, takes a blunt stance on the metaproblem, starting with its title: Quit Your Job.

Working even a good job cramps your sense of possibility, imposes narrow objectives, and eats away at the little things that could grow into big things if they weren’t so oppressed by the rigors of existing structure.

I’ve seen this with my friends, in how they are full of ideas and adventurous spirit a few months after I convince them to quit their jobs. The world is full of ideas and opportunities to explore, but it takes time outside of structure to even adjust your eyes to the landscape of possibility.

I quit my job in February 2021, close to a year ago. Since then, I’ve done a bit of freelance programming work, a bit of part-time work for a startup, a bit of work on a moonshot project of my own, thanks to a grant. Right now, I’m totally unemployed and I don’t know what my 2022 will be made of. So you could say that my full-time activity is solving my metaproblem.

My friend Daniel quit his job earlier than I did, in 2020. Only a few months ago did he feel that he solved his own metaproblem. In his case, the problem he wants to work on is improving the governance and prosperity of New York City. But he tried many things, over a year and a half, before he got to something he could confidently call a solution.

It takes time to solve the metaproblem. And it’s hard to do when you work a job, or when you study with the goal of landing a job. (Ideally, universities should be all about solving the metaproblem, but in practice they don’t help as much as they could.) It’s probably even harder when you run a business — so you better hope that your business truly is solving the problems you should be solving.

Thus it can absolutely be worth quitting a job to “explore,” “try out some things,” “work on personal projects.” In an ideal world, most people who have the means (and it doesn’t even take that much) should not hesitate to spend periods of unemployment in their adult, post-student life. Fallow periods, if you will, “like a crop rotation giving the land time to bring forth new fertility,” as Wolf Tivy poetically writes.

But as things stand, quitting is scary. Having a job (or a business) is a mark of social status, and nothing, beyond the bare necessities, is more important to a human being than status. Myself, it took me several months to stop caring.

Yet it would be quite sad to see somebody build Rube Goldberg machine after Rube Goldberg machine, unable to stop, because they are afraid of losing status, or because they studied Rube Goldberg machine-building in college, or because 10-year-old-them said they would build Rube Goldberg machines when they grow up. You would want to shake that person, tell them that they’ve outsourced their metaproblem to someone else, and it doesn’t have to be that way. You’d want to tell them this is no way to live a life.

So, if your current job is a satisfying solution to your metaproblem, then good for you. But if you recognize yourself as a builder of pointless (or harmful) things, then please, quit!

Do something better with your life. Find the true answer to the question of which problem you should be solving.

You can absolutely do it, and the world will thank you for it.

Semi-relevant post-scriptum

One of the ways I’m trying to solve my metaproblem is deciding what I should do with my JAWWS science writing/publishing project. A few days ago, I wrote my first post in the newsletter, and it would mean a lot for my motivation if you subscribed.

Also, as I wrote in that post, if you are involved in any way in science publishing, if you’re a scientist who’s annoyed by science writing norms, or if you care about readability in science, I want to talk to you! Contact me by email at hello@jawws.org, or send me a DM on Twitter.

Thought provoking. A very good question indeed. One I shall start to clarify in my own mind

As someone on a gap year trying to solve the metaproblem before going to uni, this was nice to read. Thank you