Of all the idea machines currently being built, effective altruism is perhaps the most fascinating. It’s the one I think about the most (on par with progress studies). That might be because, for whatever reason, there are a lot of effective altruists in the parts of the web that I hang out in. Or it could be because effective altruism has reached a critical threshold and just gets talked about a lot nowadays.

What is effective altruism, exactly? According to the Effective Altruism website, it is “a philosophy and community focused on maximising the good you can do through your career, projects, and donations.”

Now that the community has grown pretty big, that involves a bunch of organizations such as 80,000 Hours, who try to help people make their careers more impactful; the Future Fund, which directs a large amount of funding to various causes; GiveWell, which assesses the quality of charity you can give money to; the Effective Ideas Blog Prize, which encourages bloggers to discuss related ideas; the core EA forums; and many others. As a mostly external observer, I don’t feel I have more than a vague idea of the cartography of effective altruism, but I guess I know my way around.

(There’s this map from Scott Alexander, but it’s from 2020 and is definitely outdated:

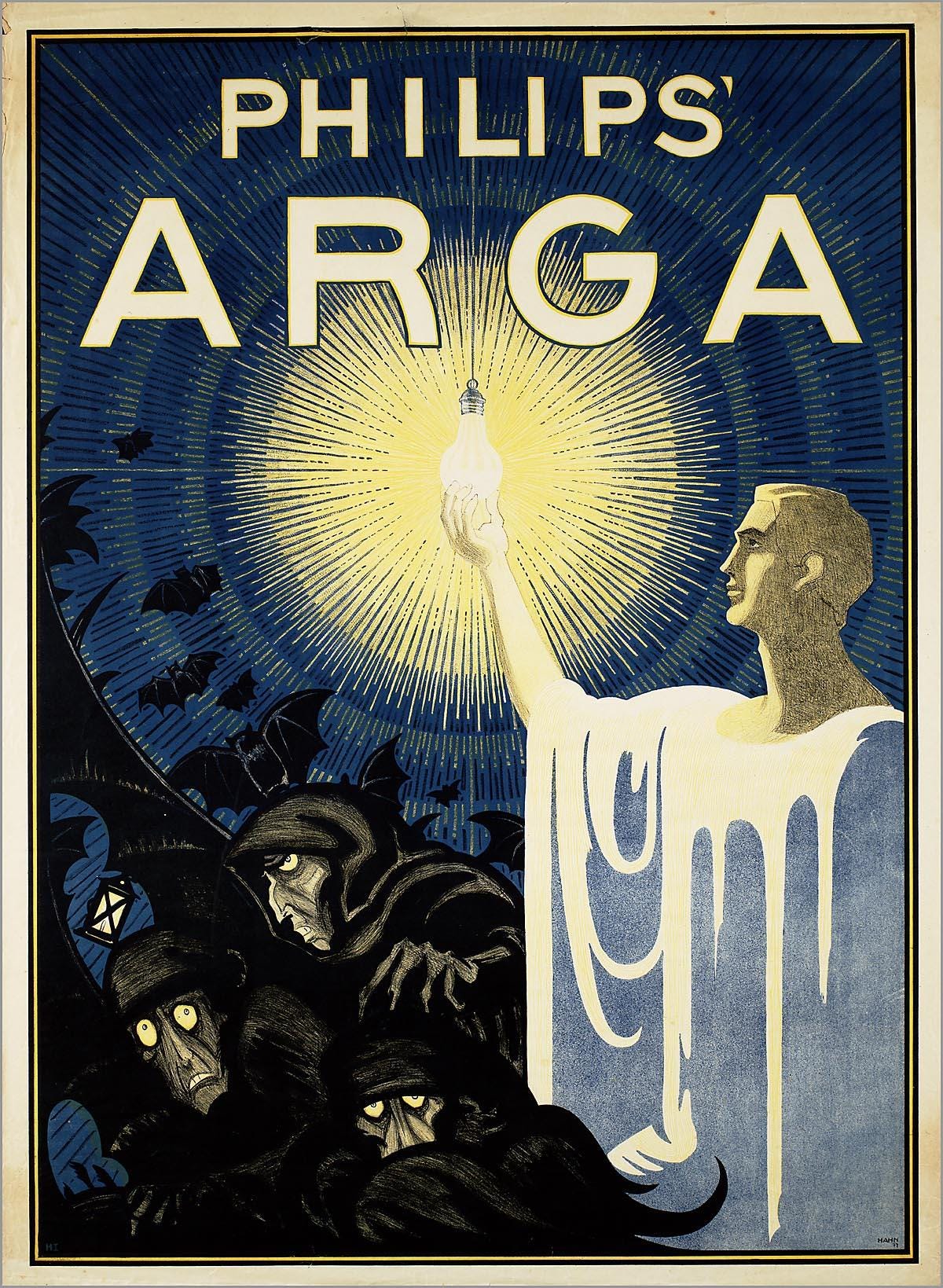

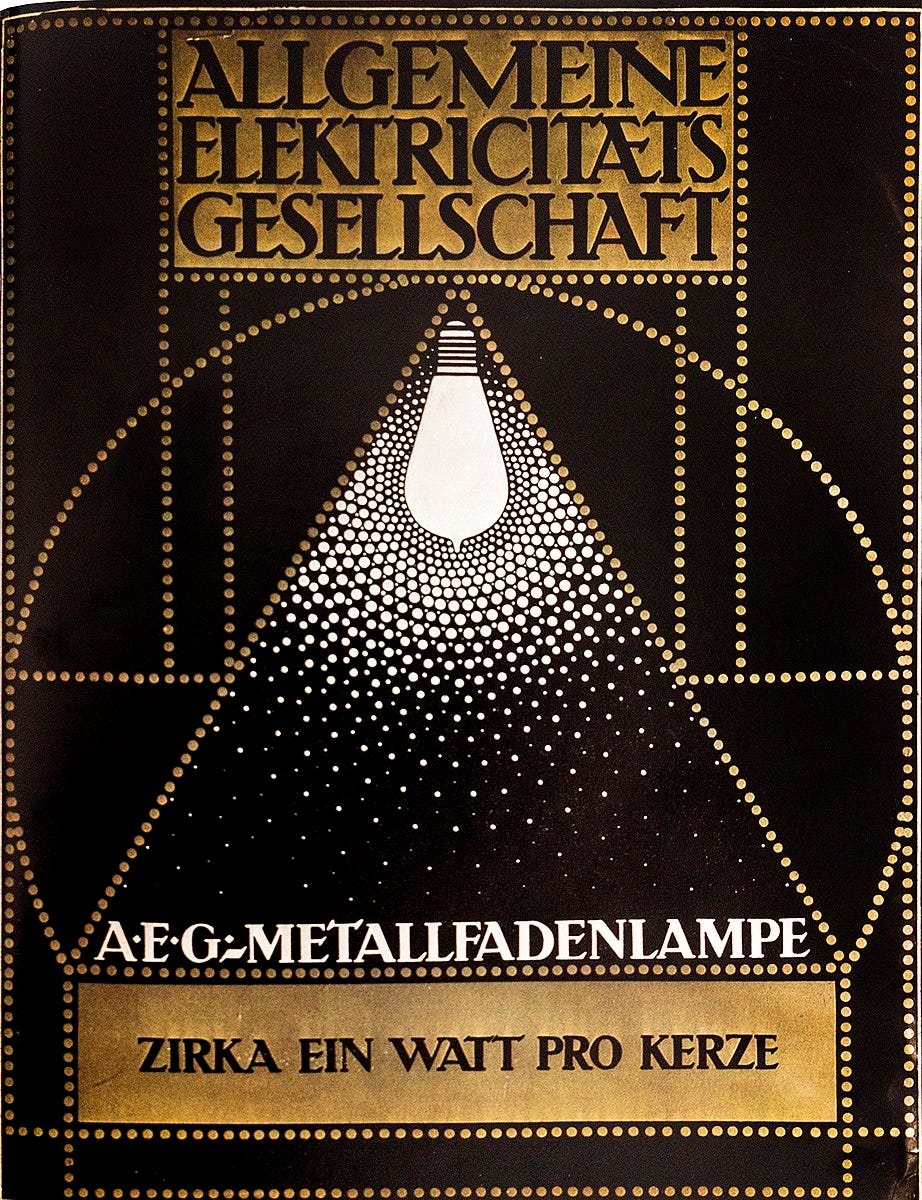

Not having a super clear idea of the ever-growing space doesn’t mean you can’t criticize it. In fact, there’s even a criticism contest! So a few months ago, I shamelessly used effective altruism as a case study to examine the question of aesthetics for social movements. My intention was less to attack effective altruism than publicly puzzle on why I wasn’t attracted to it. I hypothesized that effective altruism is especially bad at using art and storytelling to make itself appealing, and that this is problematic for three reasons:

Without good aesthetics, it’s more difficult to attract members, funders, and the other pieces needed to have a well-functioning idea machine.

Art tends to be neglected by effective altruists, who can then lose a crucial source of meaning, feel bad, and become less effective.

Without strong aesthetics, it’s tricky to define your values and express them to the world.

The essay was read and discussed by many people in the movement. It sparked some interesting discussions. But as an outsider, I partook only superficially. I had expressed my critique, and I was done.

Yet I have continued to think about effective altruism. Moreover, since I now made my case, and realized that some people were willing to listen, there was no strong reason to be repelled by the movement anymore.

And so at a time where effective altruism gets increasingly criticized on various grounds, I surprisingly found myself to be attracted to it more than ever.

When I wrote the essay on beauty and movements, I thought that the first and third arguments were the most compelling. The second, on how, without art, a movement like effective altruism can fail its own adherents, felt somewhat weaker. Yet now I think it may be the top one.

Many people have been pointing out that effective altruism can be totalizing of dehumanizing. Here’s a recent one:

The argument goes: effective altruism means maximizing the good you can do. That means you should relentlessly optimize. Every single thing you do either is or isn’t the most good you can do. If it isn’t, then you should change. Keep going, and soon enough you have become a dour person whose sole source of meaning is optimizing everything, and who is agonizing over even the tiniest decisions.

I wouldn’t say this is necessarily what happens to most or even many people who identify as part of the movement. Frankly, I don’t know. There’s also a lot of nuanced discussion about critiques like this whenever they’re published. But that’s a common enough occurrence that it’s worth paying attention.

And if I’m going to be an effective altruist from now on, I sure will do everything I can not to become that kind of person. In fact, the fear of being that person (or having to cope with the idea of being less moral than I could be) may have been precisely what drew me away at first, more so than the aesthetics.

At its core, this debate is about the idea of optimization.

Optimization is superlative. It seeks the “best,” the “most,” the “highest.” There’s no nuance in optimization: either you are at the maximum, or you’re not and should keep climbing.

The truth is, pure, mathematical optimization is almost never a good idea.

It’s not a good idea when trying to do scientific research. It’s not a good idea when trying to do art. It’s not a good idea in how you approach interpersonal relationships.

Optimization is not a good idea in general, because everything that matters in life is a tradeoff. When you maximize something (say, money given to charity), you will most likely sacrifice something else (say, money spent on your own well-being). Moreover, it’s almost always the case that some parts of the tradeoff are hidden. You may think you’re finding the right balance between the different variables in a problem, therefore having “optimized” it, but you are almost certainly mistaken.

(It’s ironic, by the way, that some effective altruists struggle with that, considering that most of them are simultaneously acquainted with AI risk, a field that essentially involves repeating “PURE OPTIMIZATION CAN BE VERY BAD” until you convince people of donating money to AI alignment research.)

Despite this, rejecting optimization also feels wrong. You’re literally saying you don’t want to most good! Doesn’t that mean that you want some amount of evil? Isn’t that bad?

Perhaps this is just a reformulation of the old theodicy question. “If God is good, omniscient, and omnipotent, why does He allow evil at all?” Maybe because relentless optimization is somehow even worse.

It’s possible that this will forever be a philosophical conundrum.

In any case, the problem with effective altruism is that it is founded on the very idea of optimization. There are tons of other people and organizations that try to do “some” good without pretending to do “the most.” If effective altruism ditches optimization, isn’t it just turning into any of those? Would that mean removing the “E” in “EA” and becoming a generically altruist organization?

I think there are reasons to think not. Effective altruism has a lot of other great things going for it. For example, it’s uncommonly receptive to criticism (have I mentioned the criticism contest?). It has a great community, smart people, good institutions, and now a pretty impressive amount of money. All of these are reasons why I’m increasingly attracted to it.

It might just be worth taking out the “do most good” part of the philosophy. Replace it with “doing good better.” It’s fine if we’re not as effective as humanly possible. Effectiveness is good, but it doesn’t have to be a goal in itself. We are allowed, and indeed should, only aim to be effective-ish.

Perhaps that’s what I’ll call myself from now on. An effective-ish altruist.

Instead of optimizing for a single variable, maybe aesthetics is a euphemism for Multi-Objective Optimization? Colin has a whole Substack about it. Also he noted on incomplete data as an issue along side bad modeling. https://desystemize.substack.com/p/desystemize-5