Five Propositions on the Future of Art

AWM #73: AI art and its consequences on meaning and beauty 🎨

We all know that AI-generated art is coming, but every new development is nevertheless rather spooky. Wait, we want to say. Is it really happening this fast?

Since yesterday, the online world is ablaze with discourse on DALL·E 2. With a name that is a portmanteau of WALL·E and Salvador Dalí, DALL·E 2 is an AI built by the company OpenAI. Its purpose is to take some text as input and generate an image an output.

It’s good at it. It’s really good at it.

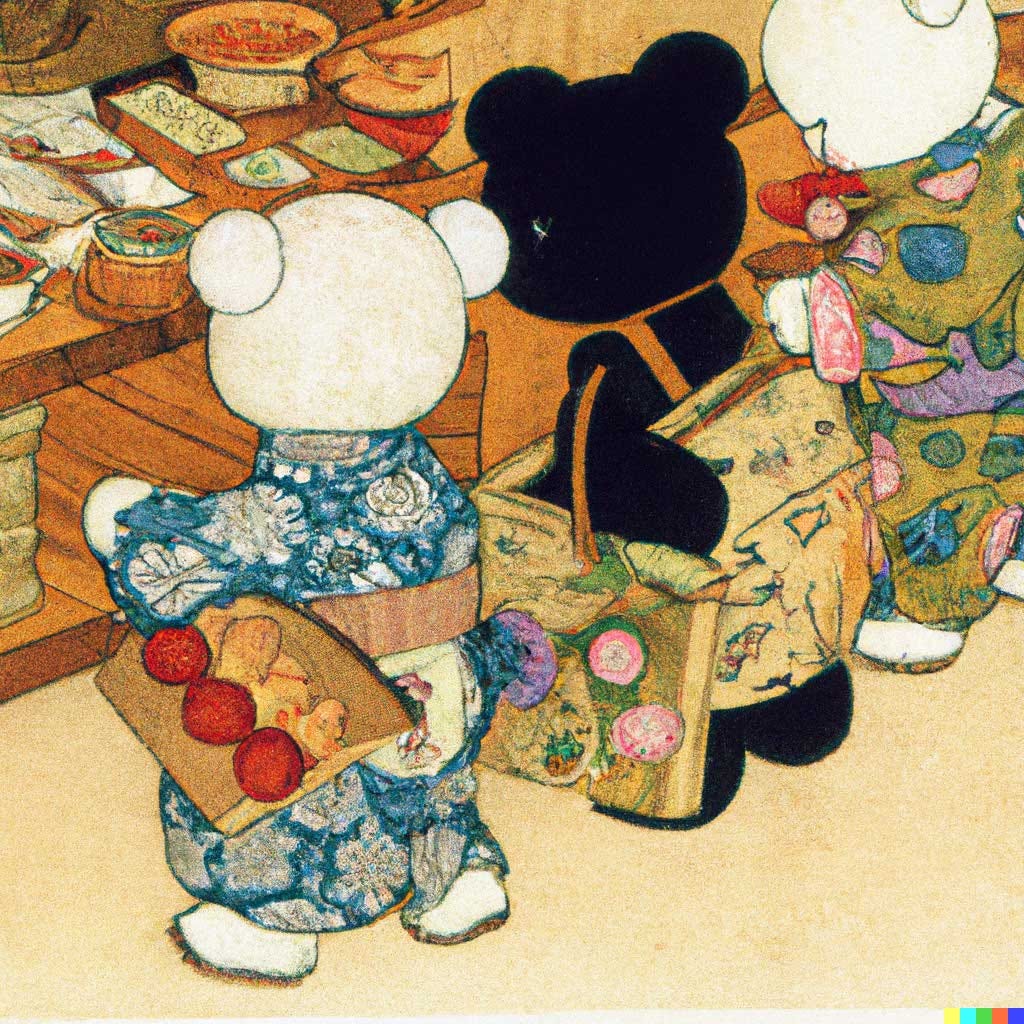

The software is not freely accessible, but you can see examples on the Instagram page or on the main website. Here’s what it can generate for “Teddy bears shopping for groceries in the style of ukiyo-e” (ukiyo-e is a traditional Japanese art style):

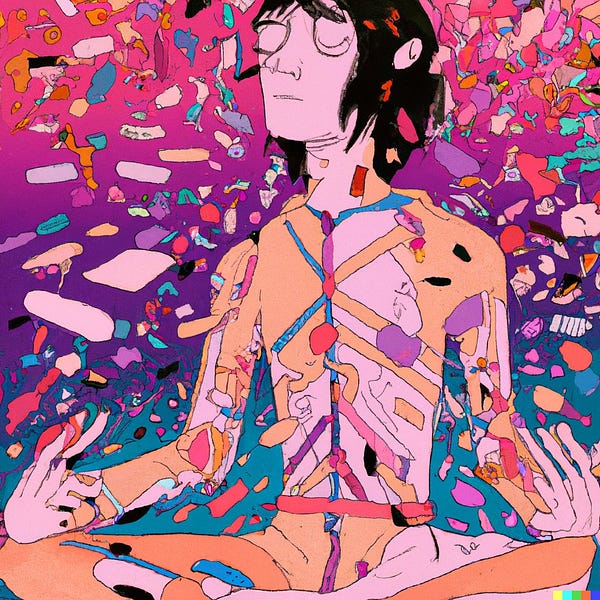

And so on. It can easily generate hundreds of these if you ask it to. It can generate art in any style (“steampunk,” “as kid’s crayon art,” “vaporwave,” you name it). It can generate art of anything that you can describe in a sentence, even weird semi-abstract stuff like “a bowl of soup that is a portal to another dimension.” Nick Cammarata generated art from the Twitter bios of a bunch of his friends, many of which are vague and conceptual, and they’re all really good:

I cannot for the life of me figure out what I’m supposed to think about this.

In the online discourse, there seem to be a big divide. There are those who think this is evil and destroying humanity’s (or artists’) purpose and meaning. And there are those who think it’s a good technological development, one that will allow us to express ourselves more freely while removing the annoying toil part of the artistic process. (And then there’s Sasha Chapin, who is appropriately nuanced and suggests that DALL·E 2 is “about 40% Satanic.”)

Who’s right? I don’t know! But let’s at least try to figure it out. Here are five propositions on the future and morality of AI art.

I. Flaws in current AI art are irrelevant.

I see some people pointing out that parts of the generated art aren’t perfectly well done, so artists shouldn’t worry: with their human qualities like attention to detail, they are still better than AI. At the very least, they will be needed to fix the flaws.

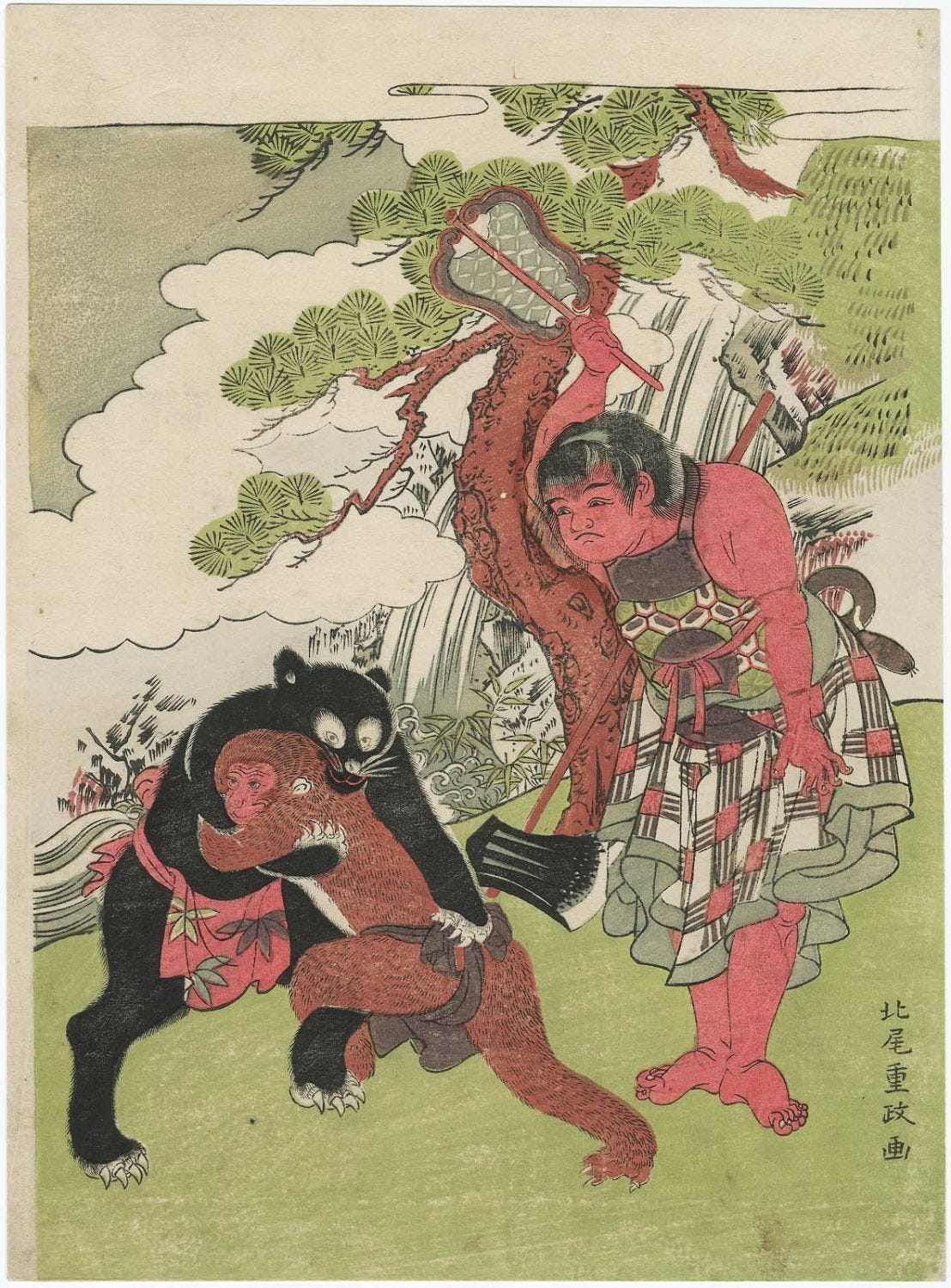

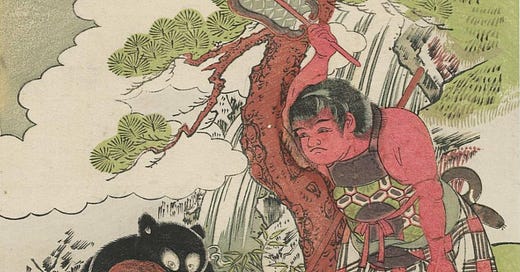

This is irrelevant. DALL·E 2 is not the final version of AI art models. They’ll be better in just a few months. Consider the same teddy bear/grocery/ukiyo-e prompt, but asked of an older AI art app, Wombo Dream, which was released in the olden days of *check notes* November 2021:

This was impressive when it was released. Now, half a year later, it looks incredibly outdated. So it’s clear that discussions of AI art need to take into account that AI will improve and probably match the level of human illustrators very soon, maybe later this year. Otherwise you’re just avoiding the question.

II. Art differs from most other work, so it can’t be analyzed through the same frame.

The history of technology offers a common pattern. A new invention (e.g. textile mills or automobiles) appears, making some previously tedious task more efficient (weaving clothing or transporting people around). The tedious task, however, is performed by certain specialized people (weavers, horse-cart drivers) who now feel threatened that their way of living may disappear. Everybody recognizes that this sucks for those people and their obsolete skills, but after a period of adaptation, we’re all better off: the task is done more economically (cheap clothes, fast transportation) and new jobs are created (operating the mills, driving cars), while the invention opens avenues for further progress, even more new jobs, and so on. Thus, even though there are immediate negative effects, we should welcome the new technology. In the long run, nobody will miss working as a horse-cart driver.

This scenario has proven true countless times! Technology so far has almost always improved the standards of life in general by creating more wealth for less work. But is it safe to assume that the same story will play out for all new inventions?

Art is different from most work. It’s usually, in some sense, fun. It creates a kind of deep satisfaction that isn’t present in non-creative work. (This is also true of other creative work like scientific research and coding.) Art is also usually seen as one of the most meaningful human strivings: the thing we do when we have taken care of all our worldly needs.

So it seems naïve to me to apply the common tech history pattern to AI art. It’s easy to say “this sucks for illustrators but they’ll adapt; surely it’ll create new jobs that we can’t foresee.” Maybe it will. Maybe using AI to create will indeed be more fun and more widely available to people than art ever was. Or maybe it’ll also destroy one of the few sources of meaning that we could until now rely on.

And this matters, because:

III. A collapse of meaning can be harmful.

AI-generated art will not prevent humans from making art. If you enjoy painting, that’ll still be available — just like you can still sew clothes at home if you like, despite the availability of industrial clothing.

But making art will no longer be economical. If you’re the editor of a publication, why pay an illustrator $500 and wait a week when you can generate 100 options in a few seconds for a tiny fraction of the cost? Of course, not all art works like this, and indeed the best art is rarely spawned from corporate commission. But that’s one big reason to make art that will simply be gone. And when (not if) the quality of AI art gets good enough, it won’t even just be a question of cost. Humans will be able to make art, but it’ll be second-rate. We’ll be like kids, drawing cute but primitive crayon pictures next to adults who can yield the tools so much more adroitly.

Some artists, perhaps the top ones, will be able to survive this by imbuing their art with qualities beyond technical skill: personality, cleverness, or chains of meaning. You can’t create a “better” version of the original Mona Lisa; it has meaning for reasons other than just the skill of Leonardo da Vinci.

And so AI art will spark a golden age of conceptual art. Imagination will be the prime value: the bottleneck will be interesting ideas that you can write into a prompt for DALL·E 2.

But meanwhile, it’ll be less meaningful to pick up the technical skills of painting and drawing. Hobbies are cool, but they feel much less important than work that fulfills a real need. In a changing world where many experience difficulty with finding meaning, one of of the most meaningful things we can do will have collapsed.

It won’t just be the trained artists who suffer. It’ll be everyone who otherwise could have found meaning in art, and will now tell themselves, “what’s the point?”

IV. Our relationship with beauty and art will change.

Beauty is a complex thing. It seems to be a form of curiosity towards whatever we perceive as good, which may be a human universal like nutritious food, or some cultural cue like current fashion, or simply a psychological need like a quiet and orderly room when we’re stressed. Any property of a thing — its color and shapes, the sounds it makes, the stories it tells, the intentions behind it, how new or familiar it is, and so on — can cause us (or prevent us) to see beauty in it. When humans consciously manipulate these properties to make an audience feel beauty, we call this “art.”

AI poses a threat to the livelihood of artists and may cause a collapse in meaning. This will make a lot of people angry. There will be backlash. And for all these angry or depressed people, AI art will not be “good.” As a result, it won’t be beautiful.

It’s unclear how many people will think like this. Right now, DALL·E 2 is new and shiny; it is impressive; what it makes seems good and therefore beautiful. But over time, it seems possible that the novelty wears off because there’ll be so much AI art. It may become boring, provided that we’re able to tell the difference.

Then perhaps human art, if we can prove that it’s human (perhaps with some sort of blockchain certification), will become higher-status — and more beautiful. After all, we tend to like the things that are costly; rich people still pay painters to make portraits despite the existence of photography. Perhaps we will learn to enjoy the imperfections in human-made pictures. Perhaps the act of communication from human to human will become even more important than it already is.

It is possible that this changing relationship with beauty will allow some of the meaning of art to remain intact. It gives us a reason for hope.

V. We should remain optimistic.

My impression of DALL·E 2 is extremely mixed, but leaning on the side of negativity. Since yesterday I’ve actually been shaken much more than anticipated. I would like for all the enthusiastic technophiles to be right, but I can’t help but think they’re missing something crucial.

But in any case, there’s no stopping the progress in AI now, at least not in the field of image generation. The ship has sailed. We’ll adapt, somehow. Might as well make the most of it.

The physicist David Deutsch says that optimism is the idea that “all evils are caused by a lack of knowledge.” We can solve all our problems by knowing more. I generally agree, and so it would be counterproductive to call for a stop to all progress in AI. Overall I do think that unless we do something catastrophically bad, we’ll end up with more human flourishing with DALL·E 2 and its friends than without. We’ll redefine our ideas of what is good and beautiful and meaningful.

But it’ll be a rocky sail, and there is risk that the ship crashes at any point. It’s fine, and actually productive, to be worried.

Some publicity for my other stuff: The Classical Futurist has published its eighth and last regular issue, in which I wrote a post about neopaganism and LARPing.

"It’s fine, and actually productive, to be worried." love this ending. good reminder that the worrying is not just for the sake of expressing emotion, but also to actually help spot & address problems.