Around 1795, France in general and Paris in particular were emerging from an especially turbulent half decade. In 1789 the Bastille had been stormed, triggering what became known as the French Revolution. A couple of years later, the king, Louis XVI, had been guillotined. This had been followed by a whole lot of other people being guillotined as the radical government of the Committee for Public Safety, dominated by Maximilien Robespierre, relied on a Reign of Terror to get rid of political enemies. By the mid-1790s, Robespierre had been guillotined himself, and the government was reorganized into a more stable, more boring, and more bourgeois form of government, called the Directoire. It would last for four years, until 1799, at which point the main character of the story becomes a young man named Napoleon.

Now imagine you are a young person of privileged, aristocratic extraction, during the Directoire period. You just survived a period of utmost turmoil. Maybe you lost a family member to the guillotine. The economy is a mess, your country is at war with all of Europe, and your new political system is an oligarchical republic that is maybe better than Robespierre’s regime but also clearly not great, and indeed it will soon morph into an imperial dictatorship. How do you cope?

By living a life of extravagance and debauchery, of course.

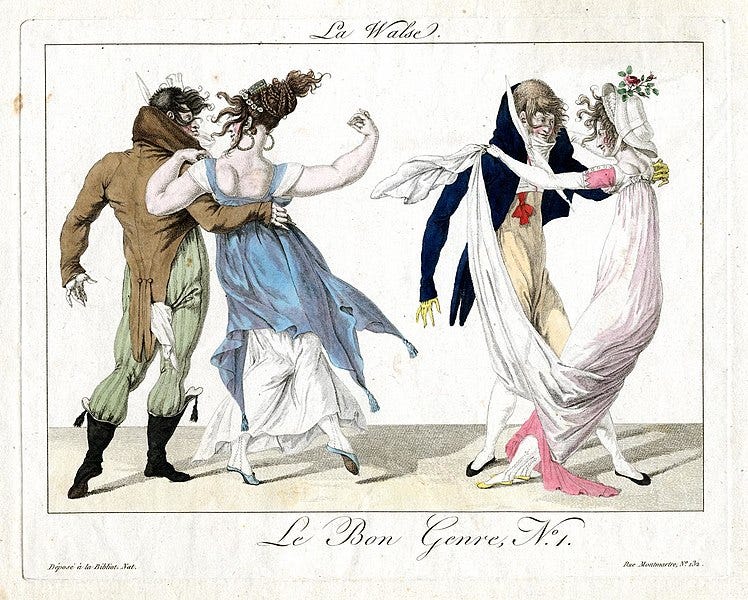

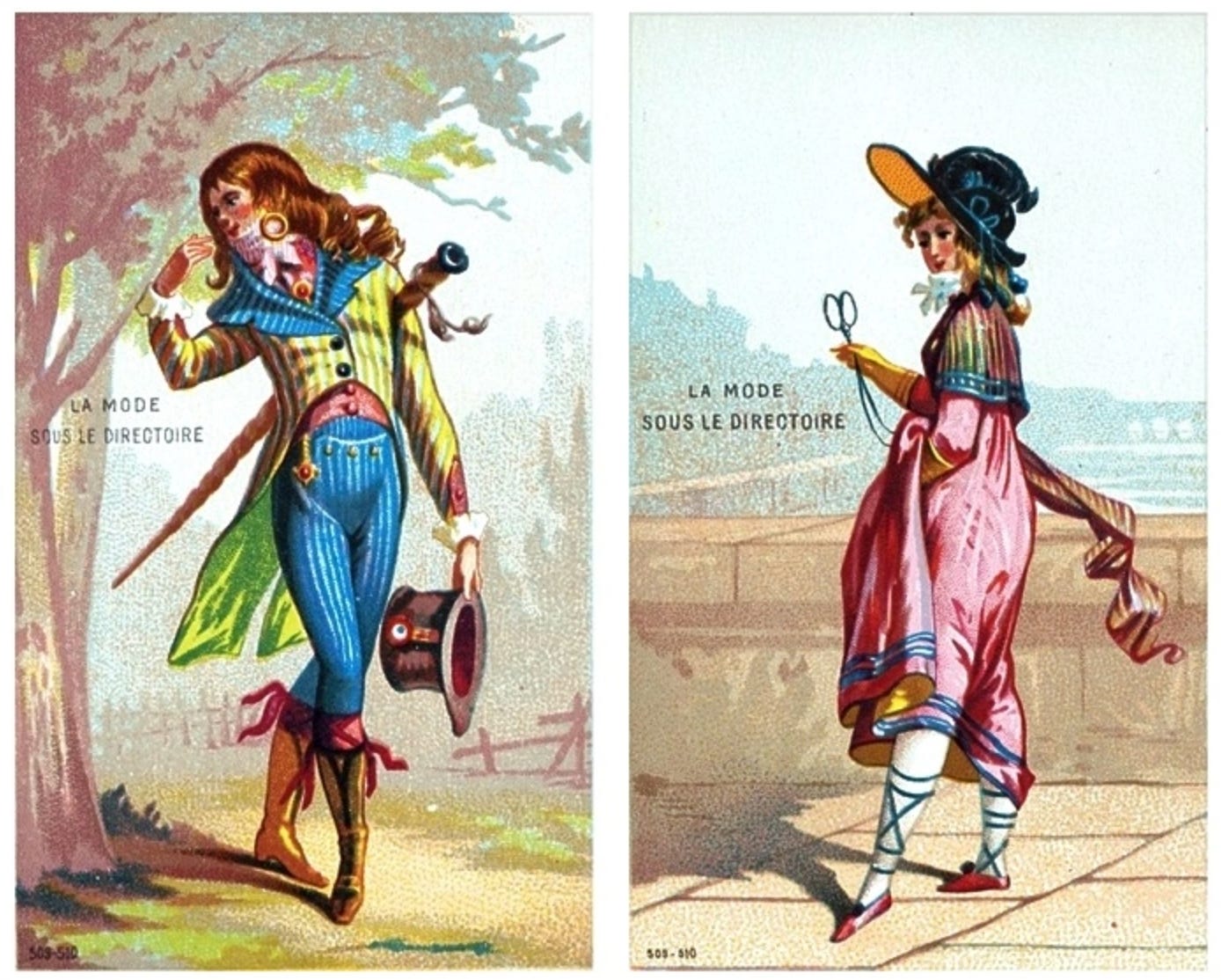

People called these young men the incroyables, and the young women the merveilleuses. The incredible and the marvellous ones. During the time of the Terror, it was better not to attract attention; but now the most ridiculous outfits were warranted instead.

The incroyables wore deliberately ill-fitting clothes, and hid the lower part of their faces with gigantic collars. They pretended to be disabled or myopic, and carried thick glasses or monocles. Their perfumes were strongly musky — they and a similar group were also nicknamed muscadins — and they wore their hair long, in a way that fell over the ears or imitated the hairstyles of the prisoners who were destined to the guillotine.

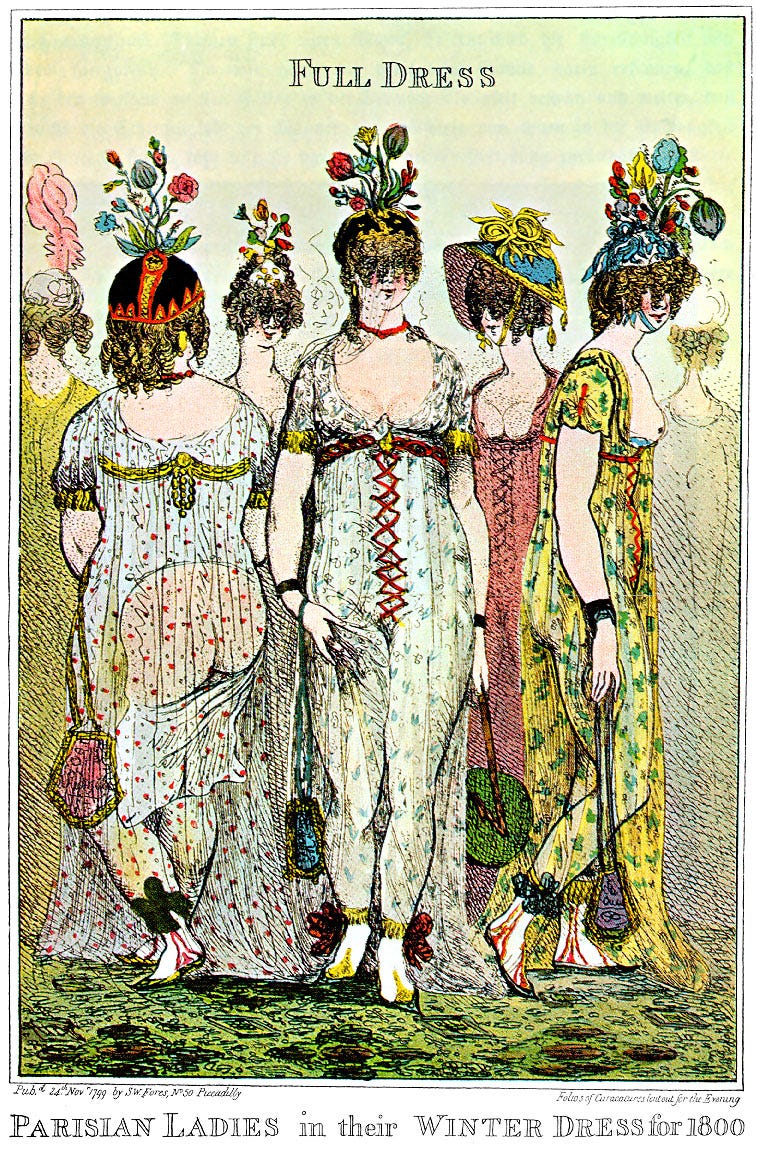

Meanwhile the merveilleuses modelled their dresses on Greek antiquity. They wore extravagant hats, and fabrics of such lightness that they were sometimes mistaken for prostitutes. The English made fun of them:

The incroyables and merveilleuses held hundreds of balls, some of which, legend says, were reserved for people who had lost a relative during the Revolution. Instead of bowing their head to greet others, they shook it in all directions to imitate the convulsive movements of a guillotined person. The incroyables and the merveilleuses also took to speaking in an odd way, not pronouncing the letter R anymore — and again legend has it that R had to be sacrificed because it was the first letter of “revolution.”

The Directoire ended in 1799 after the coup of Napoleon Bonaparte to establish the Consulat government, and fashion soon became more modest. Some of the legacy of the incroyables would live on as dandyism in 19th century England.

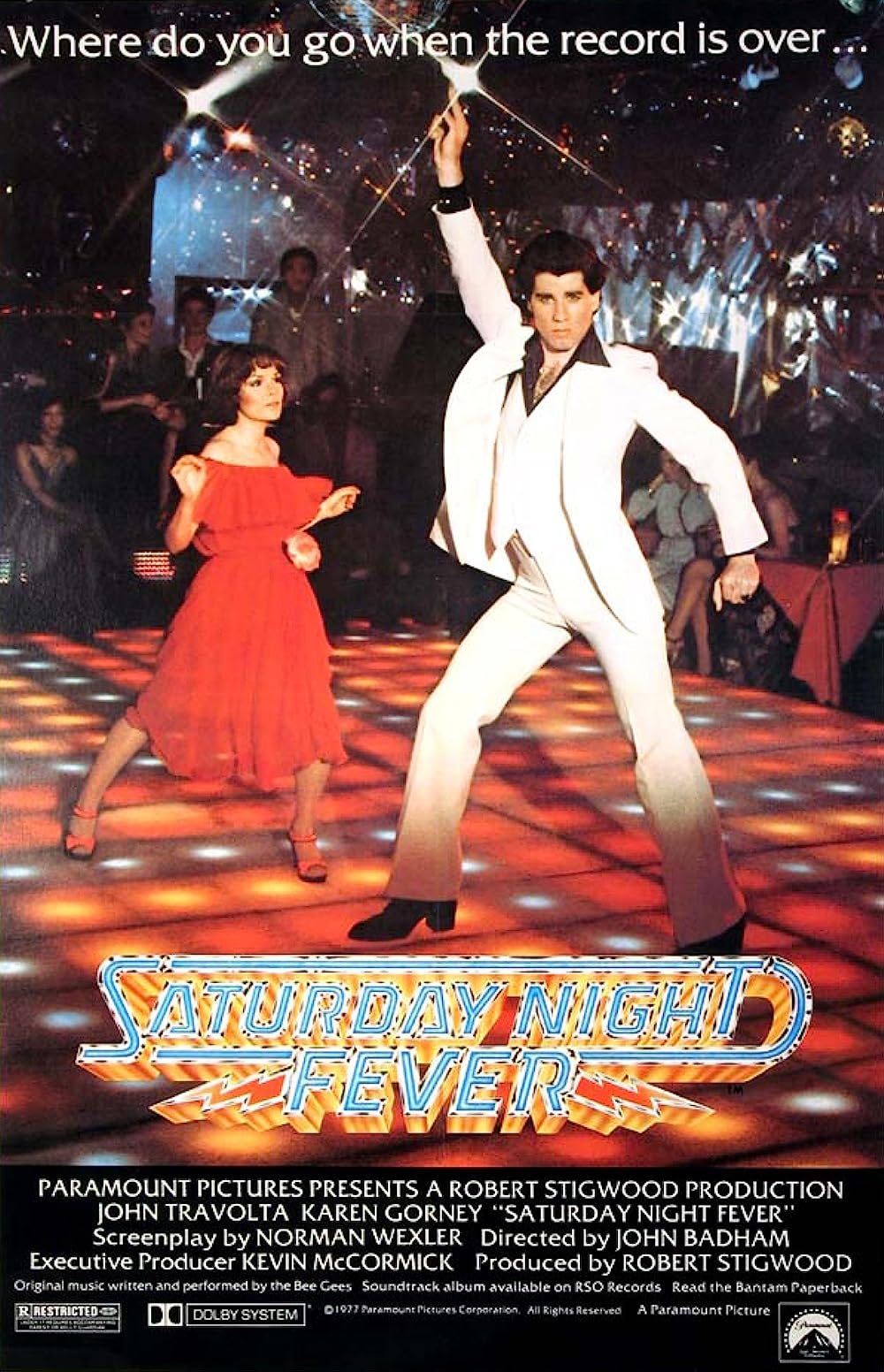

For some reason I am reminded of disco.

If you, like me, were born many years after the death of disco, you might only have a hazy understanding of disco. You know about disco balls, and you know some disco music, but you don’t really know what disco is.

(At least, I didn’t until surprisingly recently. Maybe I’m just displaying my lack of culture here.)

Disco was a subculture that began in the late 1960s, but achieved mainstream popularity in the US and the West around 1975. It decisively ended in 1979, when tens of thousands of people crowded into a Chicago stadium to destroy thousands of disco records, a night that ended in riot and led to a sharp decline in disco popularity. In the four intervening years, disco was everywhere.

Disco was a period of excess. Its aesthetics were deliberately over the top. The outfits were overly loose, overly shiny, overly colorful. The dance floors lit up, the disco balls glittered; the people danced and took drugs and had sex and partied so hard that within a few years everyone was exhausted. The peculiarities of disco music had been exploited until it was all annoyingly derivative, and after the Disco Demolition Night, everyone mostly moved on (except the Italians for some reason).

A parallel with the incroyables and merveilleuses might not exactly be warranted, and based on the overly cute fact that 1975 to 1979 is the same as 1795 to 1799, except with two digits swapped. For one thing, disco was a lower class phenomenon, especially involving marginalized people like gays and people of color, while the Directoire subculture was an affectation of surviving French aristocrats. But I do feel like there’s an interesting comparison to be made anyway.

Both subcultures represent a short outburst of cultural excess. In neither case it could last long. In both cases other people made fun of it. In both cases, the impression on the broader culture was disproportionately large.

The history of fashion and art is often described as a sequence of reactions: romanticism adds emotion to neoclassical rationalism, which itself is a reaction to the excesses of baroque aesthetics, which themselves developed in opposition to sober Protestant Renaissance art, and so on. In that ongoing process there are occasionally periods of feverish cultural innovation, like disco and the incroyables/merveilleuses. These subcultures go way too far in some highly specific dimension, consume themselves over the course of precious few years, and are fated to look ridiculous to everyone forever after.

And yet those periods of excess are, I think, healthy. They represent the times that a civilization is most alive.

One reason to believe this is that we remember these subcultures acutely. Young people (even uncouth philistines like myself) still know what a disco ball is, and disco music constantly makes minor comebacks. Though it’s harder to say due to historical distance, I think the incroyables and merveilleuses also had a long-lasting impact on European fashion in the 1800s.

The other way to tell is that it mirrors human life, too. A good life is probably mostly one of moderation and self-restraint, if you want to remain healthy and accumulate wealth — but it also shouldn’t be only that. We all need our nights of excesses, every once in a while. Our hard parties, our crazy backpacking trips with no money, our unreasonable sex, our passion projects that leave us almost burnt out. Not always, but sometimes. Otherwise do we truly live?

The question of excess has been on my mind lately, because I recently read an article about the Icon of the Seas. The Icon of the Seas is a cruise ship that is scheduled to enter service next year. It looks like this:

The Icon of the Seas is the largest cruise ship in the world. It has twenty decks, seven swimming pools, and the largest waterpark of any ship, with six water slides. Among other amenities.

Is this excessive? Without doubt.

Is it also glorious? Absolutely. And I say this as someone who has basically zero interest in cruise ships or cruises in general.

The article I read agreed with that first statement, but not with the second one. Its journalistic angle was clearly one of shame — especially environmental shame. It interviewed professors specialized in the business of tourism, all of whom said that the Icon of the Seas was bad. It’s bad to spend so many resources on this. It’s bad to pollute the seas with the ships’s exhaust. It’s bad to go on such vacations instead of local, small-scale trips. It’s bad to spend a week on a luxurious floating palace, away from the worries of the world.

All of these are fine opinions on their own. You can hate cruise ships or the Icon of the Seas and its six water slides as much as you want. I just wish that the article had balanced them with the basic fact that the Icon of the Seas is going to be an amazing experience for everyone lucky enough to take a vacation on it. All of its costs, environmental or otherwise, are actually buying us something: the possibility to spend a week on a luxurious floating palace, away from the worries of the world. And this, for a civilization, is healthy.

That article is the sign of a culture that frowns upon its excesses. I sometimes worry that we frown a bit too much, and soon the crease between our eyebrows is going to be a permanent fixture of our culture’s face. People fret a lot over their carbon footprint: excesses are bad because they’re destroying the Earth. A subset of them even talk of degrowth, as if more modest lives were a necessity. Some say that the younger generations are becoming more puritanical around things like sex and alcohol. Aesthetically, we seem to be stuck in an endless dominance of minimalist styles and, for collective projects, lack of ornamentation. It would seem wasteful to carve small creatures and gods into the façade of a public building. Whenever we actually build something unusually impressive, like the Icon of the Seas or the Las Vegas Sphere, people ridicule it instead of letting themselves be inspired.

Moderation, like I said, is healthy, and certainly some level of worrying about excesses is warranted. But moderation itself must be dosed with moderation. So perhaps we’re due for 4 or 5 years of a weird, eccentric, ridiculous, but dazzlingly alive subculture, and then a lifetime of fondly remembering it.

I’m all for a period of harmless excess as long as it does not involve queues. Standing around waiting my turn takes all of the fun out of degeneracy.

Great piece.

Amsterdam, that former European symbol of excess has just banned cruise ships!