Hieroglyphic Notes on the Most Important Century, Etched Into the Stone of a Long-Sealed Tomb

AWM #89: Is the 21st century the most important time ever? Let's ask Ancient Egypt! 𓂀

All trivia enthusiasts know that Cleopatra lived closer to the creation of the iPhone than the building of the Pyramids. But this is less about Cleopatra, the iPhone, or the Pyramids than the fact that Ancient Egyptian civilization lasted for a really long time. From the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt around 3100 BC until the deposition of the last native pharaoh in 343 BC, more than 2,700 years elapsed. Twenty-seven centuries.

Which of those twenty-seven centuries was the “most important”?

There are many ways to answer this question. We’ll examine four — and then, of course, we’ll generalize far beyond Ancient Egypt, and ask whether we are living in our most important century.

The first possible answer focuses on the origins. Everything that has ever happened was a consequence of things that happened beforehand, which were consequences of yet earlier things, and so on until you get to the beginning. The most important century of any civilization, then, would be its foundational period: the root cause of everything that would later be important to that society.

In the case of Egypt, the foundational century would be the 32nd or 31st century BC. (This is approximate, as records from that period are scarce.) That’s when the first pharaoh of the First Dynasty, Narmer, unified the northern and southern parts of the Nile valley into a single state. It was also, roughly, when the hieroglyphic writing system was developed, marking the end of Prehistoric Egypt and the beginning of Ancient Egypt.

Of course, the events of the First Dynasty themselves have their causes in earlier events, but unless you’re going to say that the most important century of Ancient Egypt (and everything else) was the 100 years following the Big Bang, you probably want a cutoff somewhere.

The second answer is the end. The most important period for a civilization could be defined as the time when it stood at a critical juncture, and failed. Clearly, nothing can be more important afterwards, since the civilization doesn’t exist anymore. And any previous critical juncture surely wasn’t that critical, if the civilization survived it.

There’s no single clear point for the end of Ancient Egypt as a distinct civilization. The country was conquered by foreign empires many times over its long history, but native dynasties always eventually seized back power, until they didn’t. In 343 BC, the last indigenous pharaoh Nectanebo II was defeated by the Persian Empire. Eleven years later, the Persians surrendered Egypt to Alexander the Great, and for three hundred years Egypt was a kingdom governed by the Ptolemaic Greek pharaohs — the last of which was effectively Cleopatra in 30 BC. After that, the title of pharaoh was carried by Roman emperors until 314 AD.

When did Egypt cease to be Ancient Egypt? The Ptolemaic kingdom and Roman Egypt were Hellenicized, but they were still culturally Egyptian. Religiously, the pagan gods gave way to Christianity in the 4th century AD, and then Christianity gave way to Islam in the 7th. All of these transitions were obviously important. Alternatively, one could argue that Ancient Egypt never truly ended, and that the ethnically Egyptian people living in the Nile valley today are simply the latest incarnation of an ever-changing culture.

In the interest of picking a cutoff, we’ll say that Ancient Egyptian civilization ended in the 4th century BC, when foreign conquest began the irreversible process of transforming the culture into something different — and that’s our second candidate for that civilization’s most important century.

The remaining two answers have to concern events that neither started nor ended Egypt. These events could be (and that’s our third answer) periods of prosperity, innovation, and social progress, the kind of centuries that leave a lasting legacy: golden ages. The most important century of Egypt, then, would be whichever century produced the best cultural output.

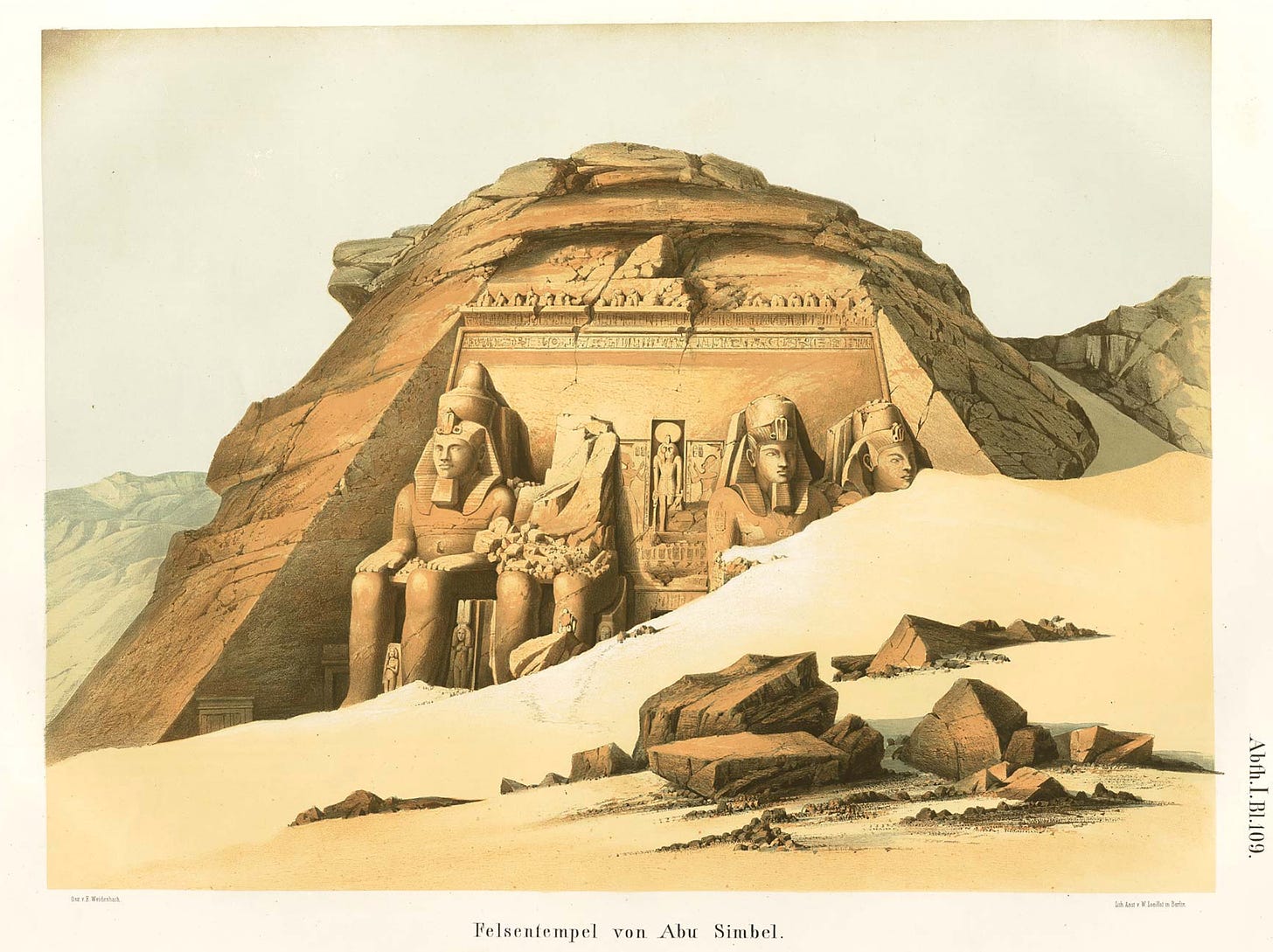

One candidate for this is the 26th century BC, when the Fourth Dynasty reigned and built the Great Pyramids of Giza. Another key century would be the 15th BC, when Egypt reached its largest imperial extent under Thutmose III and his mother Hatshepsut. Yet another century of note was the 13th BC, which corresponds roughly with the Nineteenth Dynasty. It was the time of Ramesses II, one of the greatest pharaohs, who reigned for 66 years; it was the time of successful conquests in the Near East; it was the time of great monuments at Luxor, at Karnak, at Abu Simbel.

Most of what you know of Ancient Egypt — in other words, its cultural impact — comes from its golden ages. That seems to match what we commonly mean by “most important,” for instance when talking about an artist’s work: it is whatever echoes the most across eternity.

The fourth and last answer is the converse of the golden age: the dark age. A dark age is a period of disturbances, lack of cultural output, and decreased living standards.

For our purposes, a dark age implies that the civilization survives and eventually emerges — otherwise we’d be talking about the end, which we already covered. Can a survivable dark age be more important than whatever eventually manages to destroy the civilization? Yes, possibly, if that end is conventionally defined and doesn’t really suggest any major changes; or if a time of disturbances, once traversed, leads to a renaissance. Dark ages are often important transitions: they are both a beginning and an end.

Ancient Egypt had its fair share of dark ages. They are generally referred to as the three “Intermediate Periods” between the more prosperous periods of the Old, Middle, and New Kingdom. For example, the Second Intermediate Period (1650-1550 BC) was one of foreign domination by the Asian Hyksos people. And the beginning of the Third Intermediate Period, which spanned the 11th-7th centuries, coincides with the Bronze Age Collapse of the ancient Near East, a general upheaval that Egypt survived, but in a weakened state.

Dark ages are called “dark” because they produced fewer monuments and records that can cast light on what happened. It is therefore difficult to ascertain that a given century was an especially critical transition. But it’s totally possible that one of them was the most important century, or at least felt like it at the time.

So, which century is the most important of Ancient Egypt? The foundational 32nd, the turbulent 17th-16th, the glorious 13th, or the apocalyptic 4th? Or something else?

The answer, of course, is “it depends.” It depends on what we were asking in the first place. Why exactly are we worrying about important centuries?

Simply put, because some claim that the 21st century — the century you are in, dear reader, unless this essay happens to survive for much longer than I predict — is going to be the most important in the history of humanity, including any previous and future centuries.

Specifically, the person claiming this is Holden Karnofsky. He wrote a long series of posts on the topic. Briefly, his argument is that:

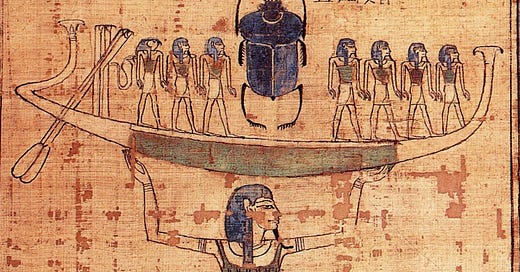

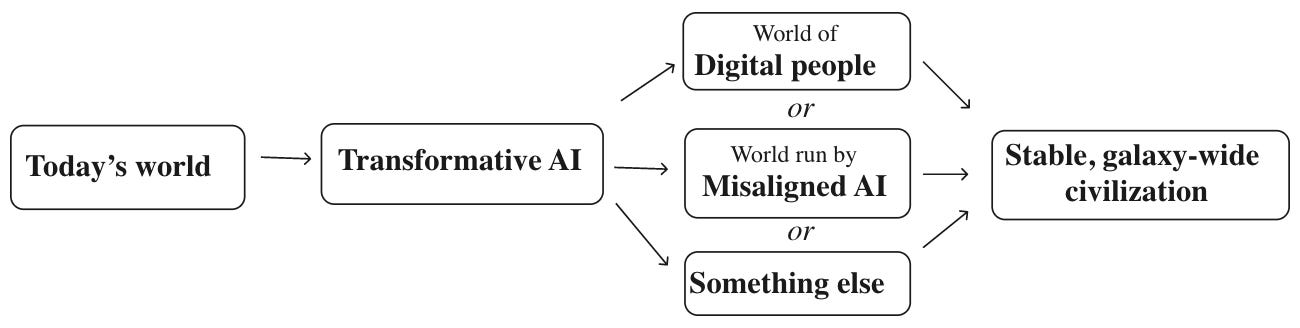

There’s a good chance that the 21st century sees the development of transformative technology, such as artificial general intelligence, or digital people or mind uploading;

Such transformative technology could end humanity as we know it: something more powerful (AI that doesn’t care about humans, or digital people who are not recognizably human) would be running the show from then on;

A transition like this could lead to a civilization that lasts indefinitely into the future with stable values;

The 21st century is therefore a critical moment to define these values and make sure that we don’t screw up.

Now, to be clear, Karnofsky doesn’t necessarily care that the 21st century is actually the single most important century. His argument can still be correct if for example “something even more remarkable happens 5 billion years from now” (as he wrote here). Instead, the point of using such a phrase is to draw attention to the high stakes of the coming decades.

Yet I think it’s worth paying attention to the phrase itself. Examining what is “most important” is a great way to clarify what matters to us, which definitely bears upon what we should do in this century.

I suspect I’m not the only one whose intuitive reaction to such a claim is skepticism. Any individual human, including myself and Holden Karnofsky, most likely feels that the most important century is whichever century they live in. It’s natural to extrapolate and say that that century is also the most important overall. That would be an instance of the chronocentrism bias, and therefore a tempting reason to dismiss Karnofsky’s argument altogether.

That’s why I opened this essay with Ancient Egypt. There’s an even larger temporal and cognitive distance between Narmer and artificial intelligence than between Cleopatra and the iPhone — and that distance is exactly the right antidote for chronocentrism. Any individual Egyptian probably felt that their own century was the most important one (or perhaps second-most important, after some mythologized origin century). There were always critical problems to be solved, after all, like a war with some Asiatic invaders, or some religious controversy, or a harvest failure. But we, thousands of years later, have a somewhat more objective view. It is equivalent to, and easier than, imagining what a person from the year 5000 would think of us.

So having done this, let’s use our four answers from above and apply them to ourselves. Are we, as Holden Karnofsky suggests, in the most important century?

I. The Origins

The 21st century is certainly not the beginning of the universe, or life on Earth, or humanity, or civilization, or industrialization. In an absolute sense, the most important century can be defined as the origins of whatever property of today’s world you care most about.

For example, if you care that:

the world exists at all — then the most important century is the 100 years after the Big Bang.

the world is inhabited by living things — it’s some century 3.5 billion of years ago when life first evolved.

the dominant life form is self-aware humans — it’s the point in the last few million years when the most crucial human characteristics appeared.

those humans are organized in complex societies — you’ll want to look at the beginning of civilization, roughly the 31st century BC.

those societies are rich and innovative — you may enjoy learning about the 18th century, with its Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution.

In the same vein, the 21st century could be the beginning of some new property. If Karnofsky is right and a technology as transformative as AGI or digital people is invented, then we may enter an era that is qualitatively different from everything in the past. Future people may look back and consider that we’re the equivalent to the Egyptians living during the time of Narmer and the First Dynasty.

Put differently, we could be like Prehistoric Egyptians living on the cusp of the transition to Ancient Egypt. The Prehistoric Egyptians presumably had stories about their origins which were important to them. But those stories would soon be superseded by newer origin stories that would feel more important to almost everyone who lived later.

Moreover, Karnofsky has an interesting argument against picking some long-past century as the most important one:

You could say that actions of past centuries also have had ripple effects that will influence this future. But I'd reply that the effects of these actions were highly chaotic and unpredictable, compared to the effects of actions closer-in-time to the point where the transition occurs.

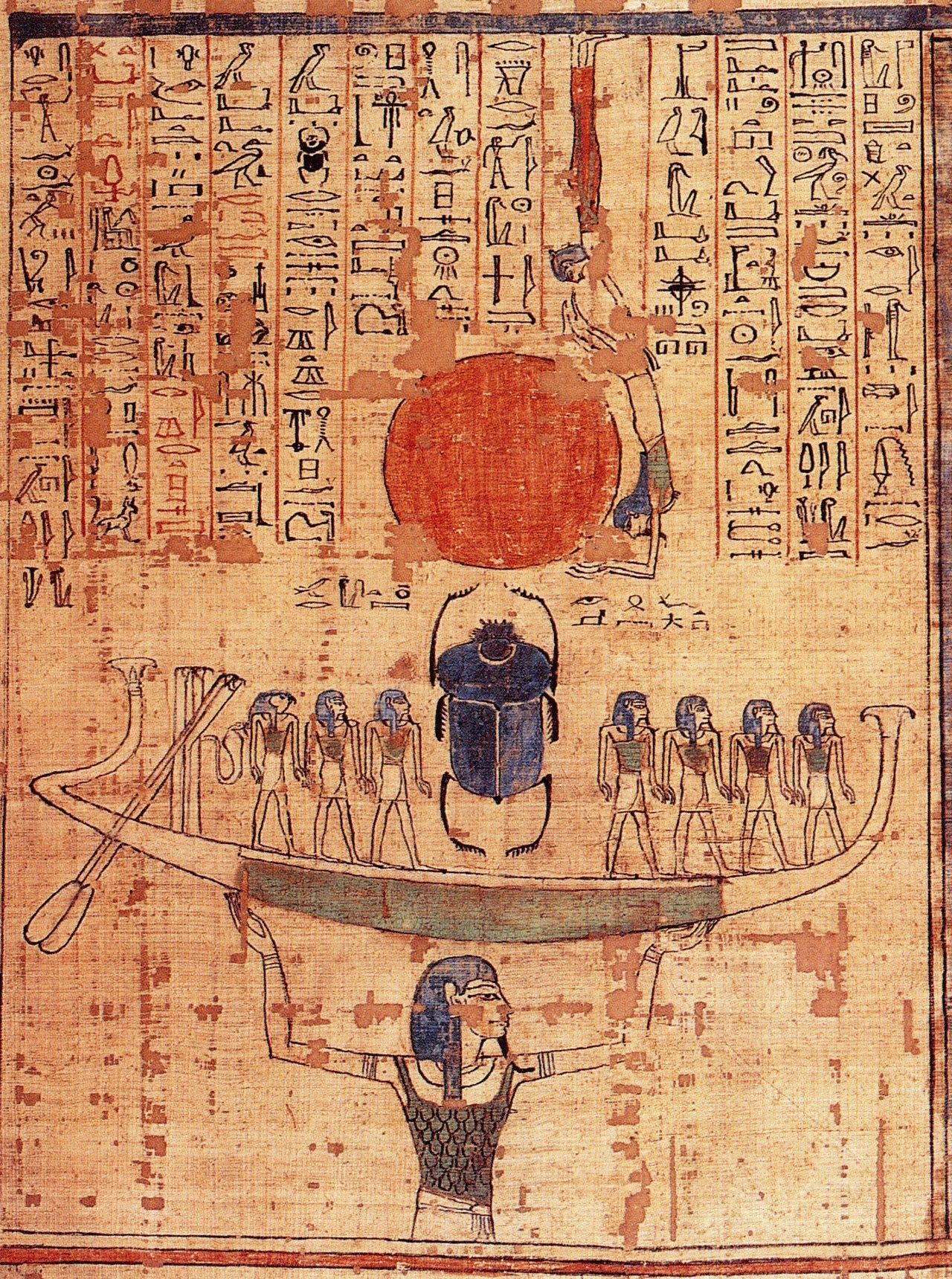

In other words, it makes sense to pick a cutoff that is as close to your most important transition as possible. It’s not super interesting to say that nothing after the Big Bang (or the Lifting of the Sun into the Sky by the Primeval Abyss Deity, whatever you prefer) mattered as much as that one primordial event.

II. The End

If we screw up royally — wait, no, that’s not strong enough. If we screw up cosmically — then the 21st century could be the most important in the sense that it’s when we failed.

Such a failure could take several forms. We could nuke ourselves into extinction. We could undergo a disastrous ecological collapse. We could develop misaligned AI, that is, AI whose goals are different from ours, and which destroys us in the process of achieving them. We could create posthuman beings that are so distinct and repulsive that their takeover of the future is, to us, a catastrophic moral outcome.

Warning against this is, I believe, the main point of Karnofsky’s posts. We might interpret them as saying, “This could be the most important century. So can we all make a real effort to ensure it isn’t?” If the extinction (or obsolescence) of humanity has to happen, let it happen as far into the future as possible.

Similarly, we can assume the Ancient Egyptians cared about their own culture, religion, and values. If their civilization was to end — because of a transformation into something that isn’t Ancient Egypt, like Greek or Roman or Arab Egypt — then it was in their interest that that end happened as late as possible.

III. The Golden Age

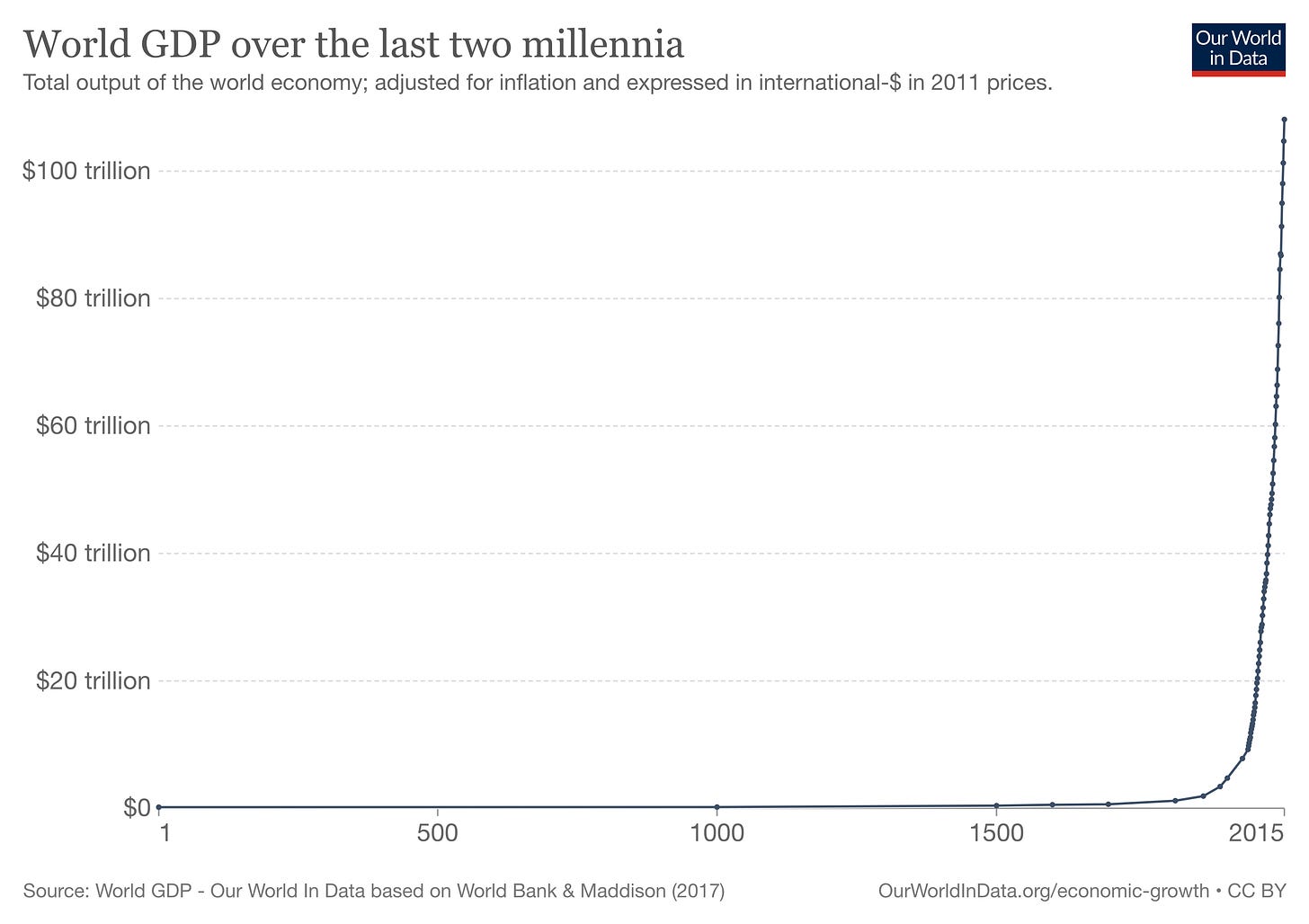

The question of whether we live in a golden age is one that I’ve pondered several times, notably in an essay on the Athenian Golden Age. I think there’s a strong case to be made that our era is indeed one of incredible prosperity, abundant cultural production, and high living standards. Nothing in the past comes close. So the 21st century, whatever problems it may have, is as golden as an age ever was.

But the 21st century can be the “most important” only if it’s more golden than all future centuries, too. This would imply that everything will be downhill from here, or at best, stagnating.

To be clear, we don’t want that.

Assuming that we don’t go through an extinction event or a transformation that qualifies as a new beginning, then we want the 22nd century to be more prosperous — and therefore more important in the golden age sense — than the 21st. Then we want the 23rd to be better than the 22nd, and so on.

Even though I don’t think Karnofsky had the golden age meaning in mind when he wrote his posts, it seems reasonable to also interpret them as a warning against this kind of failure. Stagnation and decline are less dramatic than extinction or obsolescence, but they’re also pretty bad. It wasn’t great for the Egyptians that the triumphant era of Ramesses II was never surpassed until long after their civilization had disappeared.

The argument gets weirder, however, when we consider long timescales. As Karnofsky writes in This Can’t Go On, the current trend cannot, well, go on forever. Environmentalists like to say that our economy cannot sustain infinite growth. This is probably correct, at least at the scale of the galaxy. If the economy keeps growing at the low-ish rate of 2% per year, then, thanks to the magic of exponential math, the economy will be 3 × 10⁷⁰ times bigger than today in just about 8200 years. 8200 years isn’t that long: it’s less than three times longer than Ancient Egypt! But 3 × 10⁷⁰ is ginormous: there are fewer than 10⁷⁰ atoms in the entire galaxy.

So it’s safe to assume that things will eventually slow down — unless something really transformative happens, in which case we’re back to the other kinds of most important centuries. Still, until we get to a point where the limiting factor is number of atoms in the galaxy, we should strive to make each century more golden than the last.

IV. The Dark Age

It feels unlikely that we’re currently in an age dark enough to qualify as the most important transition ever, although that could be the chronocentrism speaking. I suppose it would be possible that we solve most of our problems, such as climate change and various kinds of suffering, without completely transforming society — and so the 21st century could be remembered as the end of a dark age in which people hadn’t yet figured out how to live.

Another, more intriguing possibility is that the 21st century could mark the start of an eternal dark age. Such a scenario would, in a sense, combine the previous three: it would be a new beginning, the end of something we care about, and a fall from the golden age. Karnofsky calls it the “lock-in.”

A lock-in means that some authority (e.g. a dictator or a democratic government) gains so much control over reality (e.g. thanks to advanced technology) that it becomes able to prevent change to a much greater degree than we or the Ancient Egyptian have ever known. Society could then be locked into a stable state for millions or billions of years. This is difficult to imagine, since our own society tends to change a lot, but it could happen with exotic technology.

For example, imagine a future in which most people exist as uploaded minds in computer servers. The servers could run code that automatically restores a saved state whenever some property of the system drifts away too much. Perhaps everyone in the Akhetaten server is compelled to worship Aten, the Sun Disk, by performing the sacrifice of a cat every evening at sunset. If for whatever reason the proportion of people who don’t sacrifice a cat falls below 90%, then the server just reloads a saved copy from the previous week. And so the people living in the Akhetaten world will forever worship the Sun Disk, sacrifice innocent cats, and never adopt a new religion, because that’s literally a law of their universe.

My instinctive reaction to lock-in scenarios is — here also — to be skeptical. It’s really hard to predict the future! Thousands of conservative civilizations in the past have tried to keep things from changing and failed. A lock-in that would last billions of years — which it would have to, if the 21st century truly is the most important one — seems borderline ludicrous.

Karnofsky recognizes the relative weakness of the argument, and responds here. The takeaway is that if a lock-in “may or may not” happen, the “may or may not” could be decided this century. And even if it turns out to be impossible, the most important century idea is still valid for other reasons.

Overall that seems like the right way to think about it. If a comprehensive lock-in of human civilization ever happens, that moment would well qualify as the most important century. In this way, Karnofsky’s series of post is, once again, a warning. We should strive to avoid locking ourselves in. Or at least, if we can’t help it, we should lock in some good, open-ended, dynamic values.

All of that said, are we in the most important century? My answer would be something like: probably yes, so far; and hopefully no, in general.

Under most definitions, the 21st century is probably more important than all past centuries, both because it’s more prosperous and because it’s closer to the future. But most ways of being more important than future centuries seem bad: either we exterminate ourselves, or we change beyond recognition, or we begin declining, or we lock ourselves into a stable stagnating civilization. Only the first answer, in which the 21st century is the beginning of something new, seems mostly good. But even then, that implies that no future development would ever be better.

Consider Karnofsky’s reaction to idea that this could be the most important century:

"... Oh ... wow ... I don't know what to say and I somewhat want to vomit ... I have to sit down and think about this one."

I… pretty much agree. I’d be very reassured if I could be certain that the 21st century will be just a boring, regular century. Let’s solve our problems, invent new things, grow wealthier, and produce cool culture, but maybe not transform everything in ways that may or may not signify the end of everything that matters to us.

Do we get a choice?

Many mythologies and religions have quite detailed scenarios for the End of Times. The Abrahamic faiths have variations on the theme of the Last Judgment. The Buddhists believe the Earth will be engulfed into the inferno of seven suns. The Norse pagans used to tell stories of Ragnarök, the twilight of the gods, when the world would drown in water and then reemerge, cleansed and fertile.

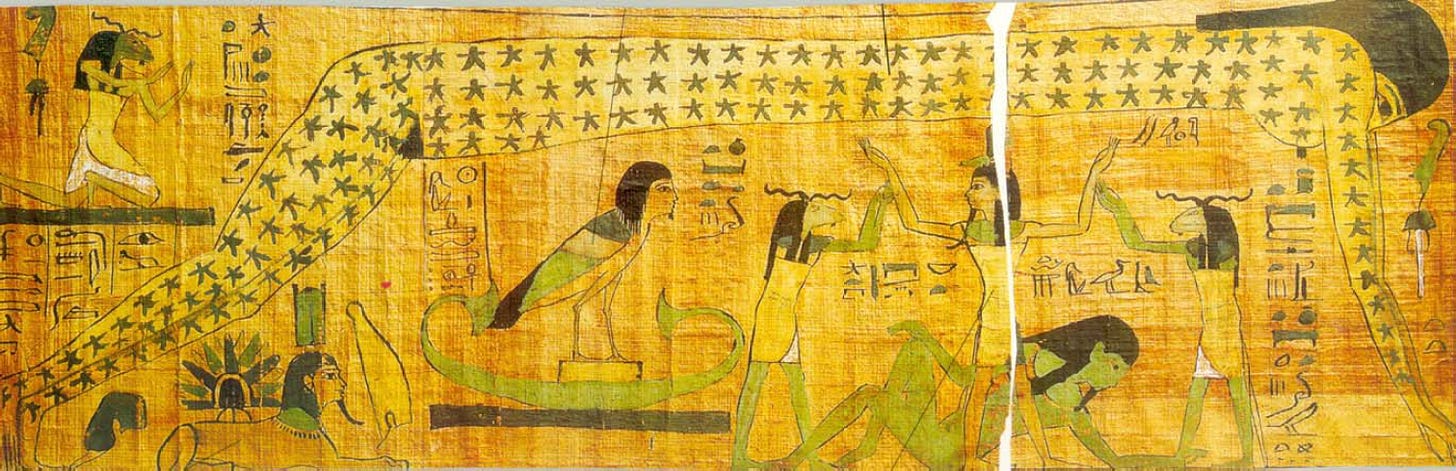

Egyptian mythology says that after countless cycles of renewal, the creator god Atum will dissolve the world into the primordial abyss from where it came. But we don’t have much more information. That’s apparently because the Ancient Egyptians viewed the End of Times not as an inevitable outcome, but as something that could be avoided.

It is fitting, I think, that one of the longest-lived civilizations had no concept of an unavoidable apocalypse. Perhaps it is also a lesson that we should learn from the Ancient Egyptians. We can choose our fate. Let’s choose well.