On (Not) Writing About Politics Online

AWM #98: Why I avoid talking about politics even though I'm an election nerd 🗳

People outside Twitter are always surprised when I tell them that Twitter is my social media platform of choice. To them, Twitter is a cesspool of stupid political arguments, a hellfire of bad takes, a vile pit of annoying people competing for attention. I generally tell them that this is all true, but also that you can easily avoid all of it. The secret is just to avoid talking about politics, and avoid following anyone who talks a lot about politics.

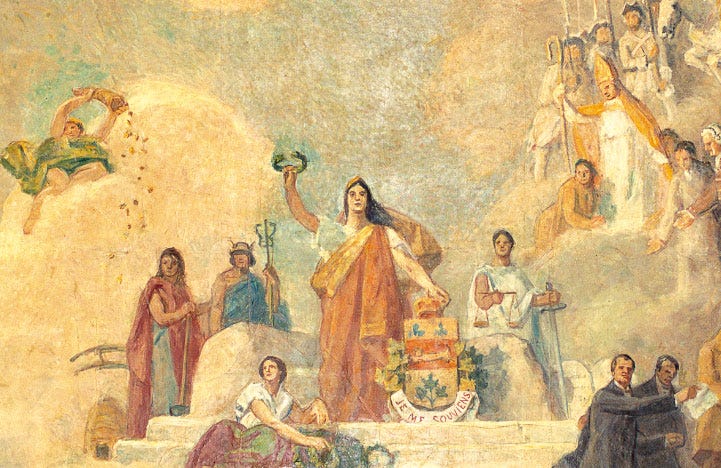

This really works, and it really can turn Twitter into a wonderful place. But also: I want to talk about politics! I’m actually a huge politics nerd! I’m the kind of person who will obsessively follow the merest detail during an election, somewhat pay attention to elections in other countries, occasionally be a member of a political party and attend their events, and even code a basic election model because I wasn’t totally satisfied with the existing ones and wanted to know how they worked. As I write this post, it is prime election season here — the Quebec general election, which to me is even more important than Canadian federal elections, is scheduled for this coming Monday, October 3rd — and this has, predictably, sucked a lot of my time and attention, to the point that I’ve been thinking less about other topics and finding it difficult to write essays.

So who do I talk politics with? Mostly with IRL friends and family, and a to some extent on a particular subreddit. This is enough, but it does lead to the weird situation that a major interest of mine is almost completely not represented in my online persona, whether on Twitter or here on Substack.

Of course, part of the reason is that politics is by definition a pretty local thing. I doubt that many of my readers would be interested in hearing more about Quebec politics. The fact that I write in English, while most of the politics that I care about happen in French, also creates a (welcome) distance.

(If you do want to learn more about Quebec politics, though, let me know. I can talk for hours about it!)

Still, kind of weird. Today I’m making an exception to the no-politics rule — although the post still is mostly about metapolitics, i.e. discussion of politics itself, to avoid boring people with the specifics. I’m writing this because I feel that the topic has to make at least one appearance on the blog, and because frankly I haven’t been thinking deeply about much else. I’ll resume non-politics posts next week.

The broader, interesting question is: why does it suck so much to talk about politics online? Why is there a cesspool, a hellfire, a pit?

The first answer is that “politics” is shorthand for “disagreement over things that affect society.” Opinions that everyone agrees about (for instance, that murder is bad) are rarely described as political. So discussing politics literally involves picking the topics for which there is the most disagreement. Unless you’re in a combative mood, this is hardly a good way to feel great and in love with the world.

The second answer is that politics involves everybody in a community. Not all of those people care, but inevitably, a significant proportion will. Also inevitably, many of those who care will be unskilled at debating with respect, being kind with people they don’t agree with, entertaining ideas they don’t like, or accepting that people have different values from their own. These are all fairly unnatural things to have skills for! They take practice! And so we end up with a lot of people discussing the areas of most intense disagreement in society with meanness and obstination.

The third answer is that there is only so much one can say about a particular political question. Since so many people care, most of whom are not particularly skilled at debate, that means, inevitably, that the same arguments will be repeated over and over and over again. If you’ve spent any significant time online, surely you have noticed this phenomenon. Write a tweet about beautiful walkable European urbanism (not the most political question, but still somewhat political), and inevitably you will get replies from people being concerned about accessibility. Maybe you’ve already thought about those concerns, and addressed them some other time; but that doesn’t matter. The same dance of arguments will be performed every time, not matter what you do. In a sense that’s good, it’s a way for people to reinvent the wheel and perhaps, occasionally, come up with a genuinely new argument — but it can get tiring.

The fourth answer is tribalism. People don’t really care that much about specific policies. They care far more about being seen as part of a group. It’s usually unpleasant to argue with someone who doesn’t really care about the object-level topic, since there’s literally no way for that debate to be productive: they won’t change their mind, since that would be betraying their tribe.

The fifth answer is that social media amplifies all of this. It’s not that social media is an inherently evil force. It just amplifies everything. The same holds true of past communication technologies, too: the printing press led to more political disagreement, and so we got the protestant reformation. It’s probably true that social media has crossed some line, though: we now have access to a more powerful flow of political information than our brains can handle, which was probably not the case before.

Many people, upon reflecting on ideas like the above, will come down with depressing conclusions: We can’t do politics well. We’re bad at taking collective decisions. The best people tend to avoid politics, leaving the field open to incompetent careerists.

(There’s a lot of such complaints about Quebec politics at the moment, unsurprisingly.)

I don’t fully agree with this view. It’s true that we could do politics better, of course. There’s always room for improvement. But I suspect that “annoying discussions about social disagreements by mostly unkind people on social media” may be as good as it’s ever been.

It’s better than politics being an exclusively elite activity, as it was the case for most of history (and still is in many places). It’s better than having people not care and let politics happen to them. It’s better than gatekeeping political discussion by any means whatsoever. In other words, the tribalism, the meanness, the repetitiveness, are all features, not bugs. They’re signs of a healthy democracy.

To be sure, they’re annoying signs! There’s a whole class of things out there that are really annoying but are still better than not having them. Some examples are gentrification and moderate inflation — annoying to deal with, but far better than economic stagnation or deflation. Stupid debates are stupid, and yet they’re preferable to absence of debate. Or worse: the resolution of conflicts through violence.

And meanwhile, there’s a lot of reason to like politics nevertheless, if you can get past the annoyance. Competitions can be fun to watch (or participate in!). And there’s something interestingly authentic about politics: it really matters! In a way, it’s a game, but it’s unlike most games and sports where deep down you know that it won’t change much either way if Team A wins over Team B or vice-versa. During election season, a lot of energy is unleashed, across an entire society, and while there’s a lot of negativity, the energy itself can be inspiring and a pleasure to watch.

Most of the time, I’m happy to let my interest in politics mostly dormant, and just go seek political writings when I need it. But right now, I’ll just enjoy the last few days of this special time before shutting up about politics for another long while.

I'd also add two ideas :

* The emotional part of politics drains many people. I've often read that people should care more about it with their head and less with their heart. But that's hard to do in any context.

* People are quite reactive to policies announcement. They often don't understand all the steps that are needed to put into practice a law (for better or worse). They can end up disappointed or frustrated if something takes too long, or on the other way, they can start worrying a lot while an announced law might not actually happen.

Very nice read! I'd definitely like to read more of your texts on politics if you feel like doing some more!