The Figurative-to-Abstract Art Pipeline

Pioneers of abstract art all have a background painting representational pictures 🐄

A funny thing about abstract art is that it has non-believers. Skeptics. People who will see a masterpiece by Mondrian or Rothko and think, “this is dumb, my 3-year-old nephew could make this.” It’s funny because their 3-year-old nephew could not, in fact, make this. But also, those people, having established that masterpieces of abstract art is at the level of toddlers, are then forced to conclude that abstract art is either some kind of provocative prank by untalented artists, a scheme by upper-middle-class people to feel sophisticated and high status, or outright financial fraud.

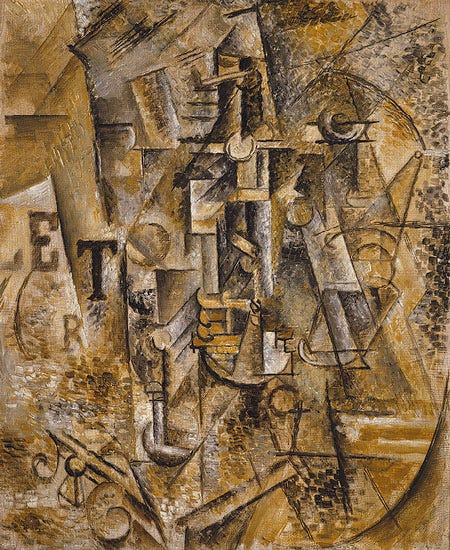

The people claiming these things usually don’t have a lot of knowledge about art history, which is why you can occasionally surprise them by the fact that Picasso, before painting extremely stylized cubist paintings like this …

… first painted fully realistic, competent pictures like this one, when he was 15 years old:

The non-believers’ reaction is often one of dumbfounded amazement: why would someone as talented as Picasso choose to paint Still Life with a Bottle of Rum when he was able to paint the obviously superior Science and Charity? The fact that he did has the potential to sow doubt in the minds of the skeptics. Picasso moving towards abstractness doesn’t square well with the view that abstract modern art is the fraudulent work of pseudo-artists with no talent.

Still, he could be an exception. So let’s look at the top 5 abstract artists according to a list of top abstract artists I generated with an LLM. The list is:

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) - Russian painter considered the pioneer of abstract art. Known for his lyrical style and synesthetic art.

Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) - Dutch painter who developed the style of neoplasticism and geometric abstract art. Famous for his grid-based paintings using only the primary colors.

Kazimir Malevich (1878-1935) - Russian artist who created suprematism, an abstract art based on basic geometric forms. Well known for his Black Square painting.

Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) - American painter famous for his drip technique of pouring and splattering paint onto large canvases. A leading artist of abstract expressionism.

Mark Rothko (1903-1970) - Latvian-American painter known for his color field paintings featuring soft rectangles of color. A major figure in abstract expressionism.

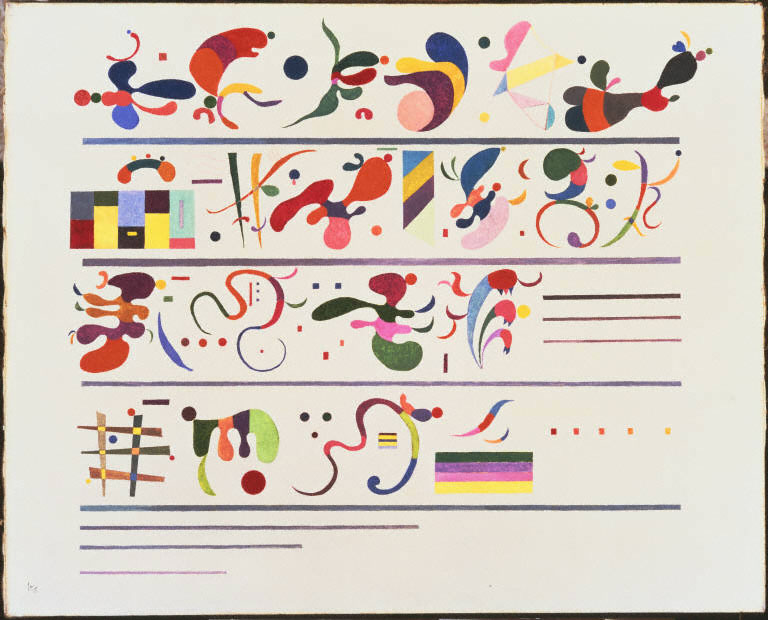

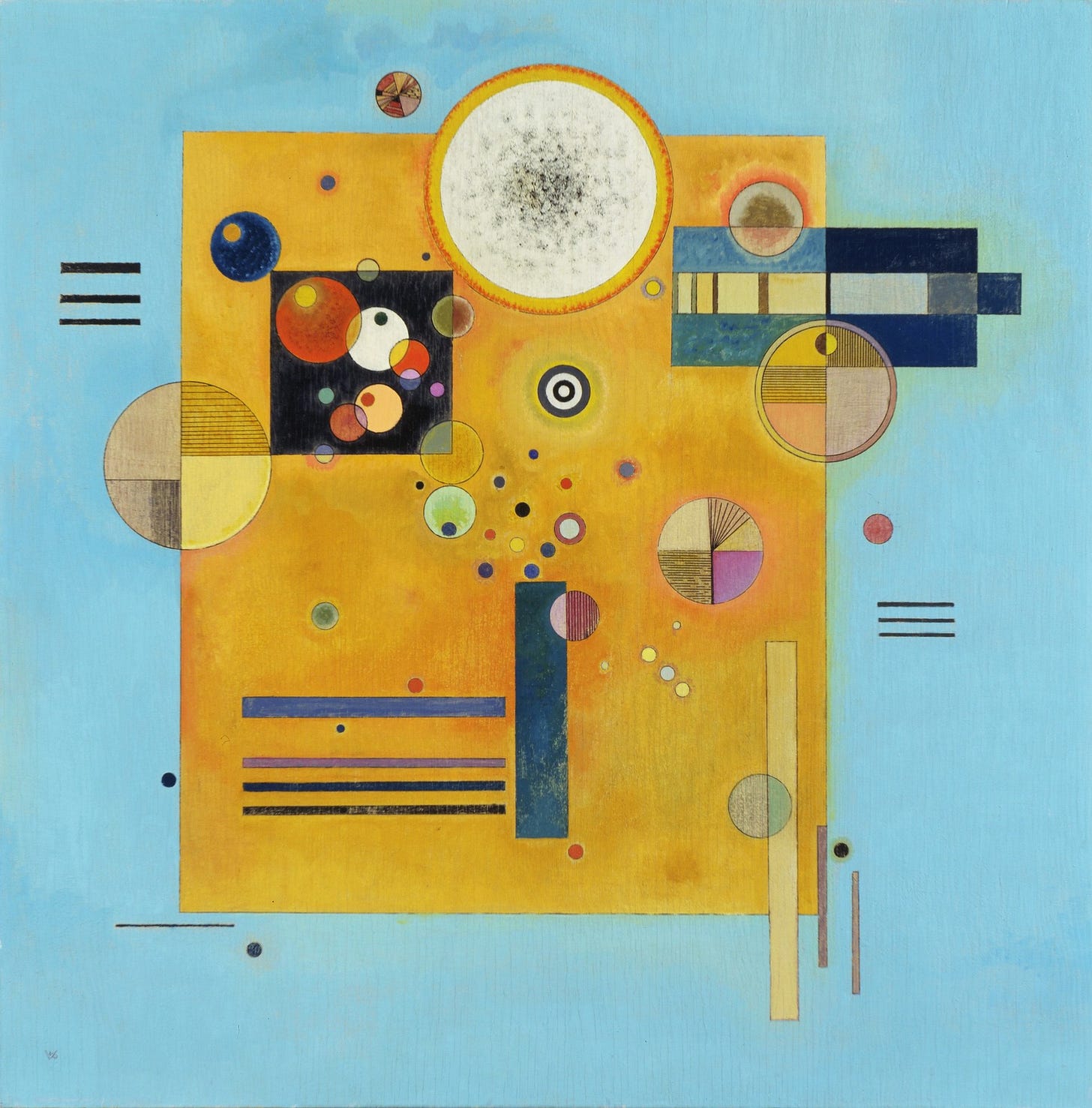

I. Kandinsky

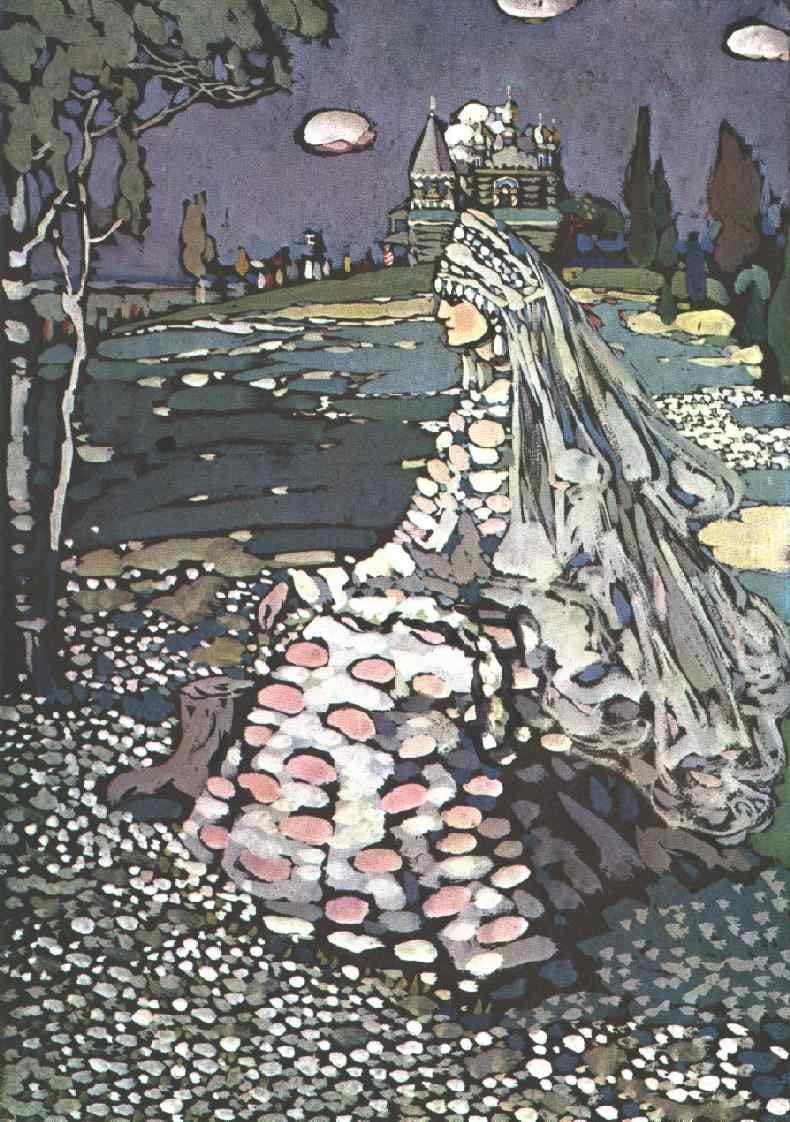

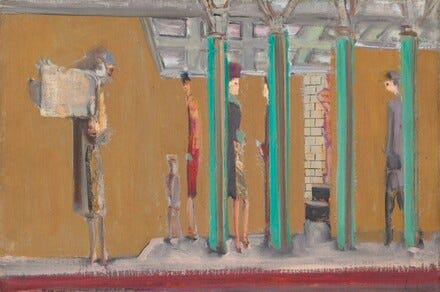

Kandinsky is known for colorful compositions of abstract elements — but it took him a while to get there. His earliest painting (that I’m aware of) looks like this:

Decidedly not abstract. Neither are his paintings for the next several years, as you’ll see from the quasi-random chronological sample below.

Things are starting to lose connection with concrete reality, but there are still recognizable figures.

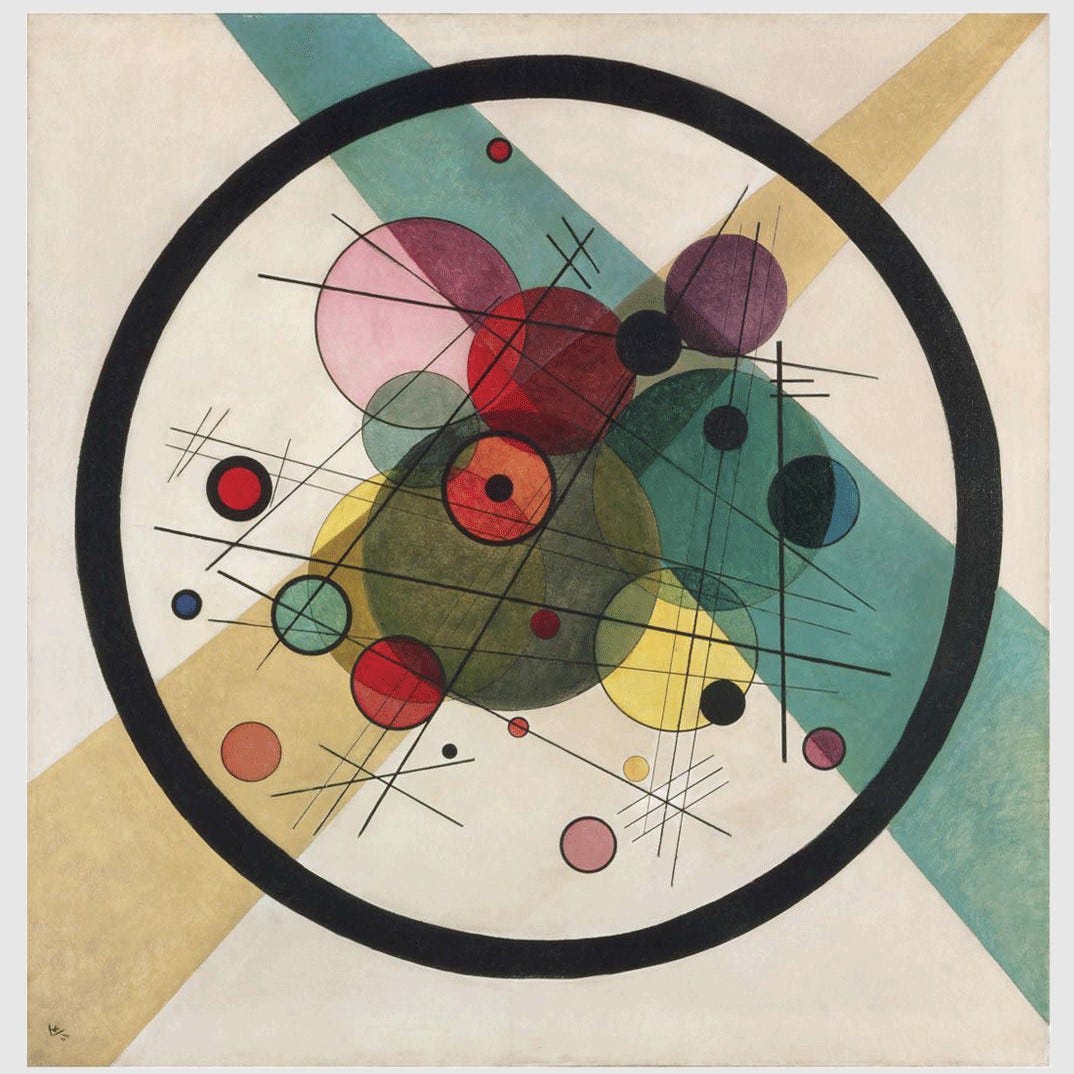

It is in the 1920s ans 1930s that Kandinsky fully developed his signature style. By this point virtually all of his paintings are complex, abstract compositions. A far cry from his earliest work.

If you want a fuller progression, see this list of all his paintings on Wikipedia.

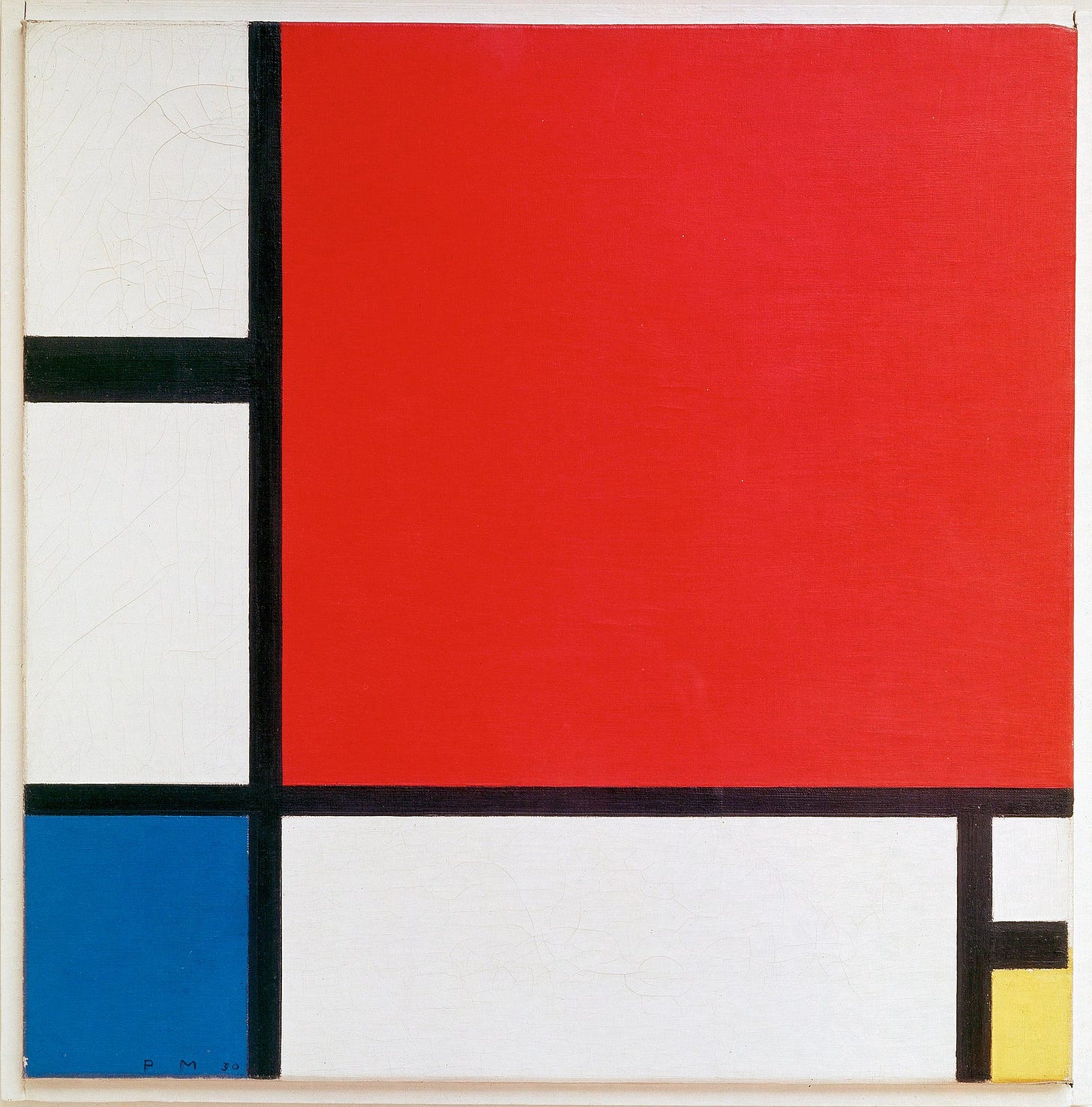

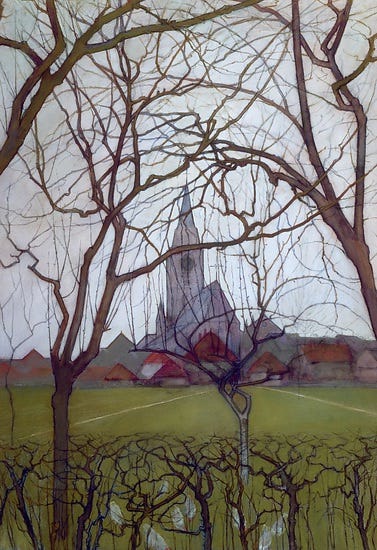

II. Mondrian

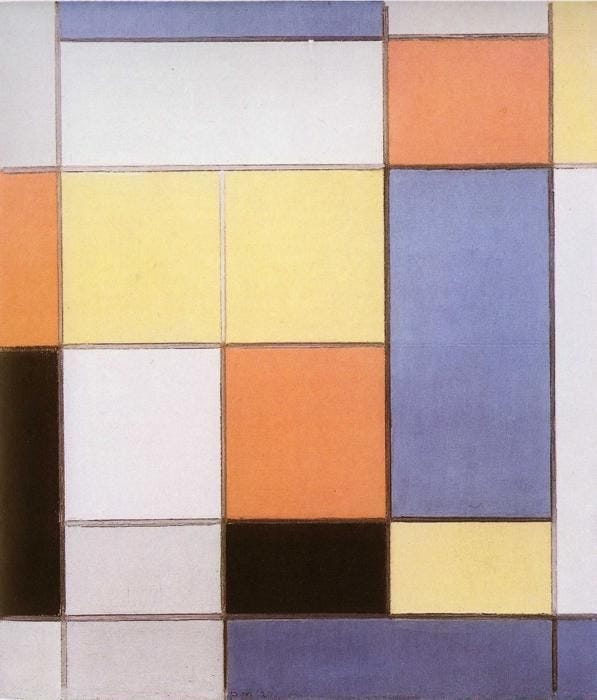

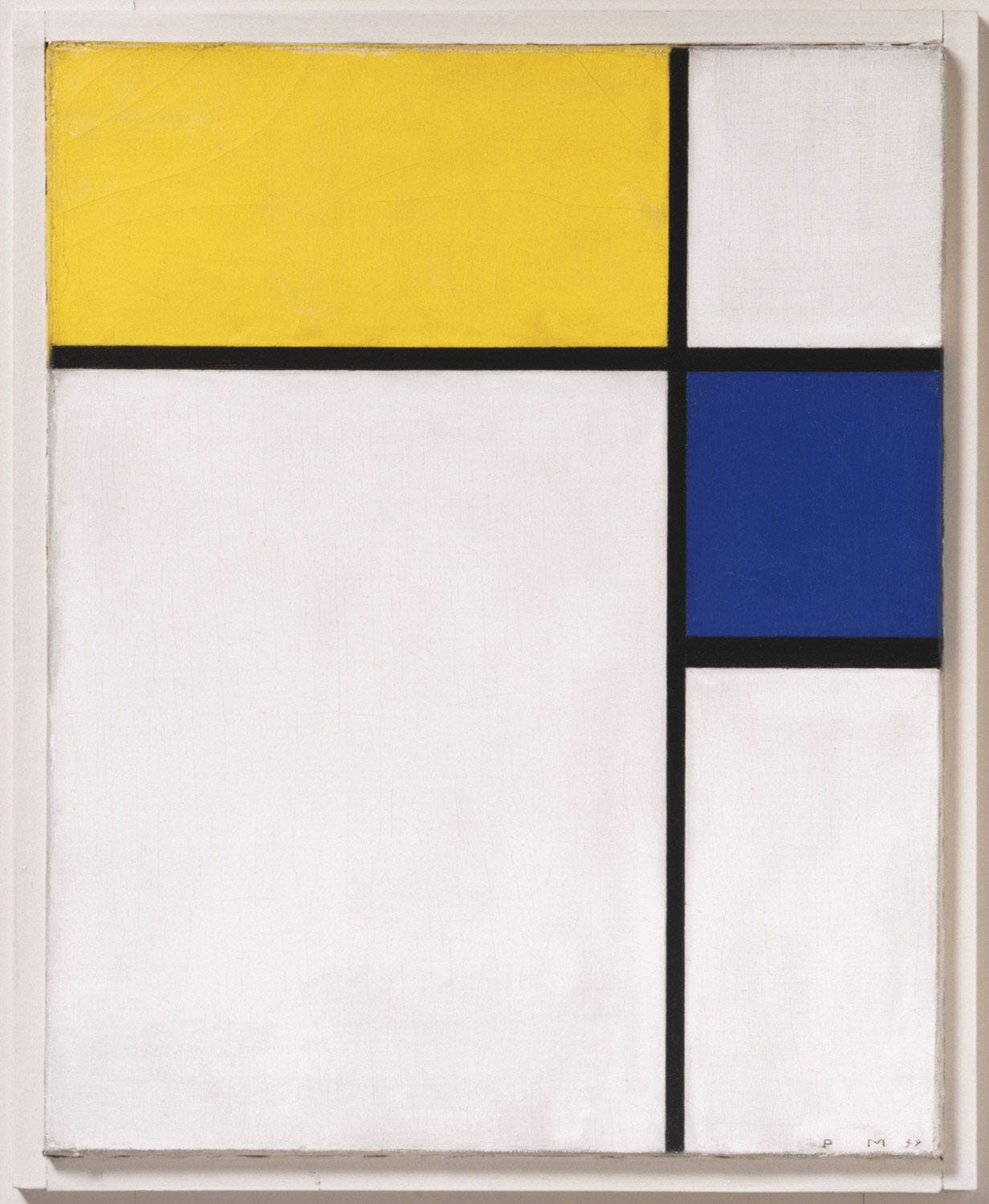

Mondrian is perhaps the most famous among abstract art skeptics, since his compositions of straight lines and primary colors seem eminently achievable by a kid. Consider:

Did Piet Mondrian draw simplistic squares because he couldn’t do anything else? Not quite. His earliest work looked like this:

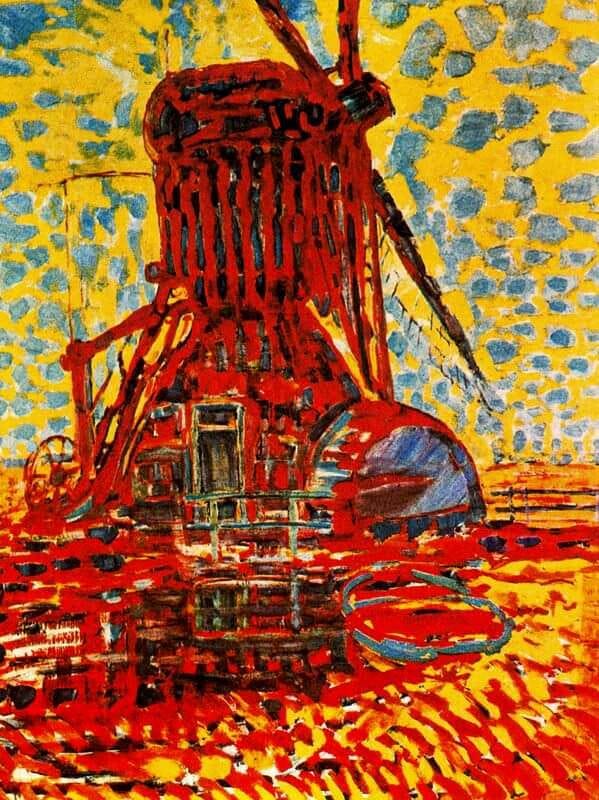

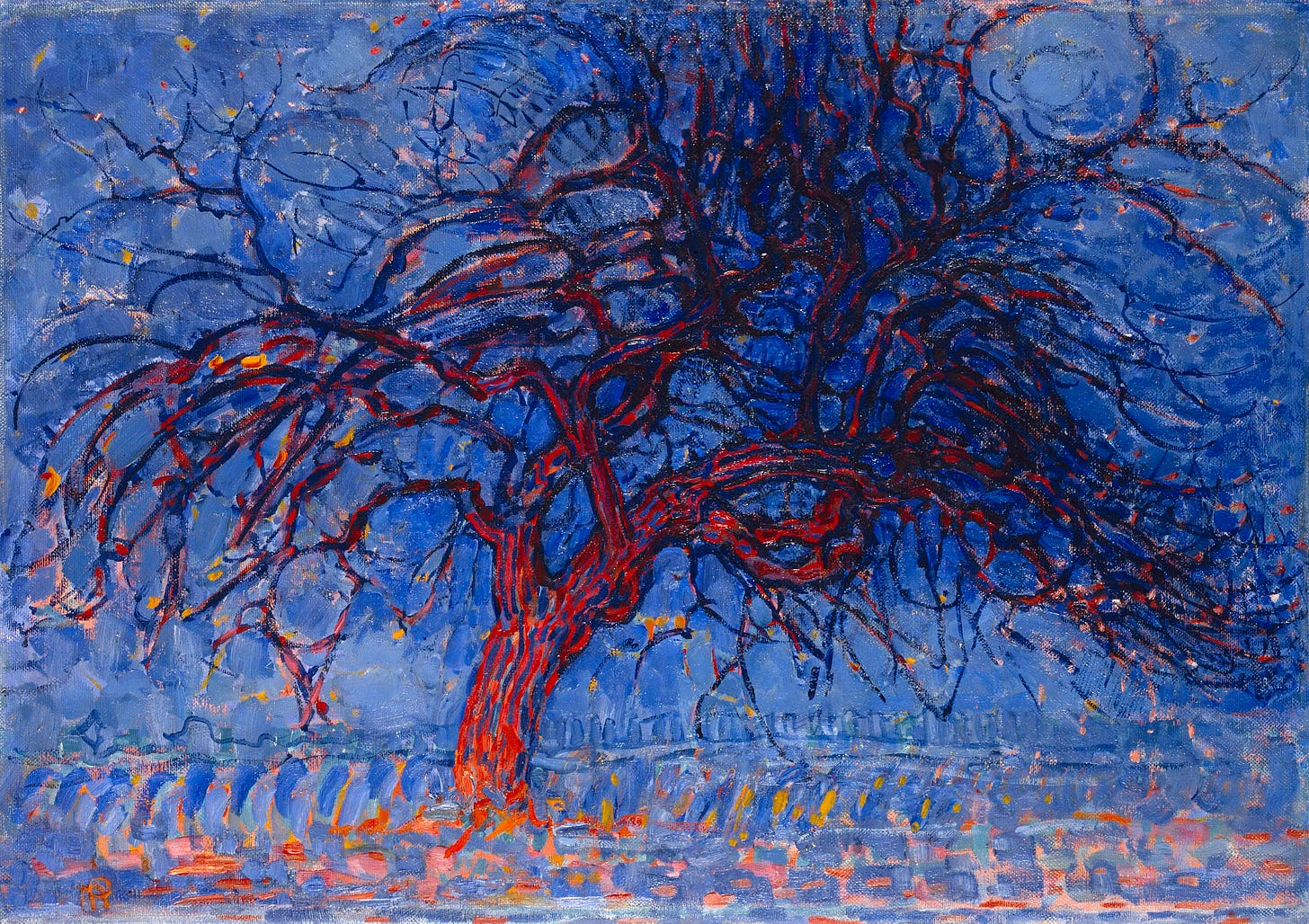

Very Dutch. Eventually, around 1908, the first hints of what will become his signature style start to appear, especially the use of strong primary colors.

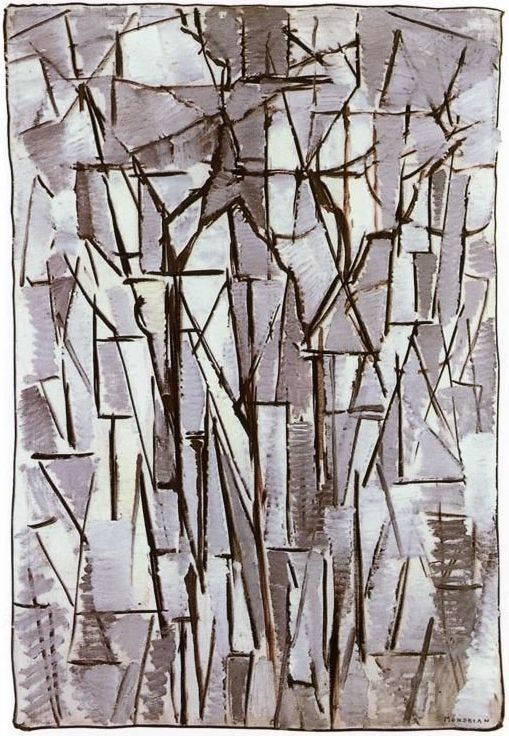

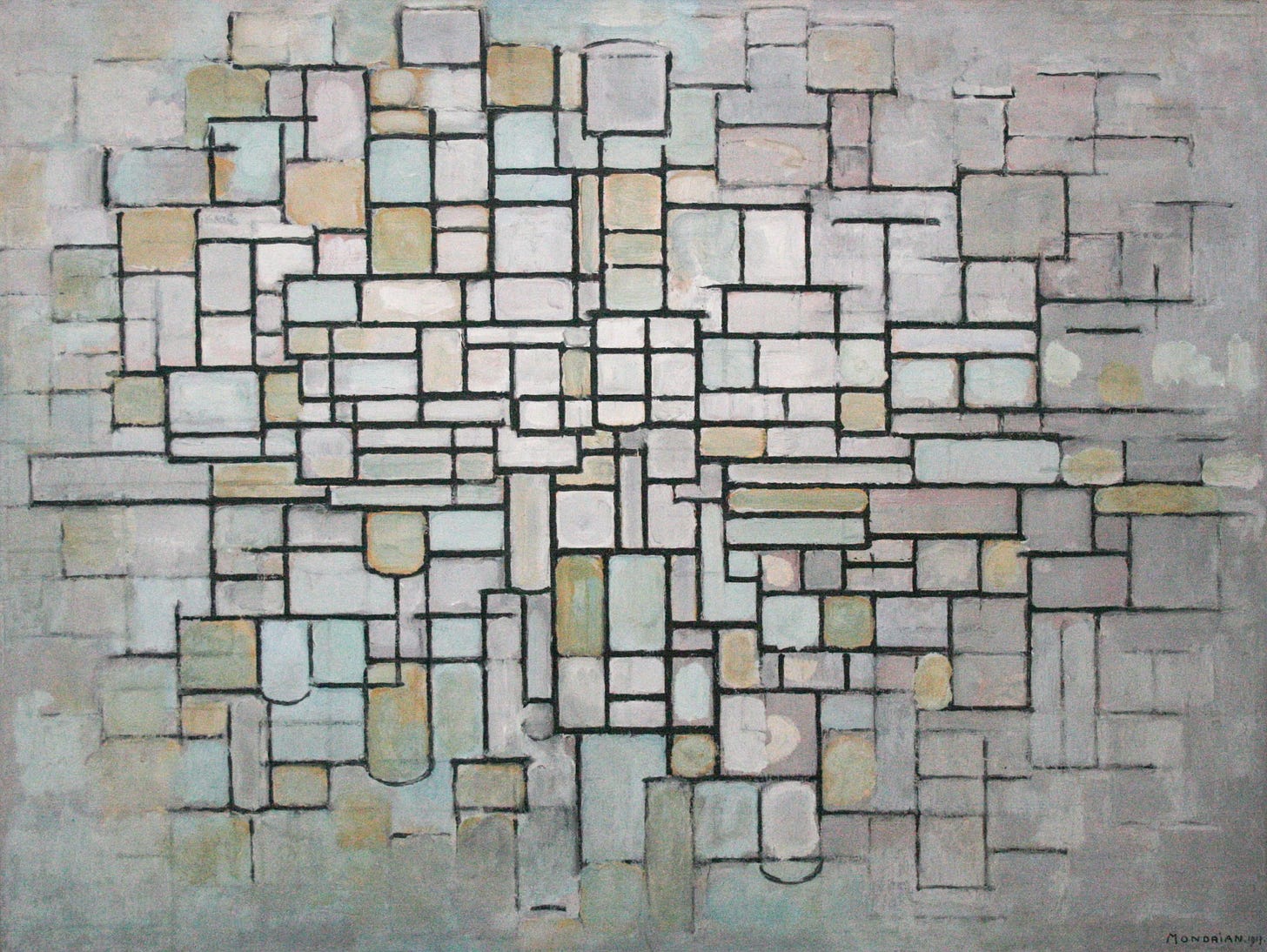

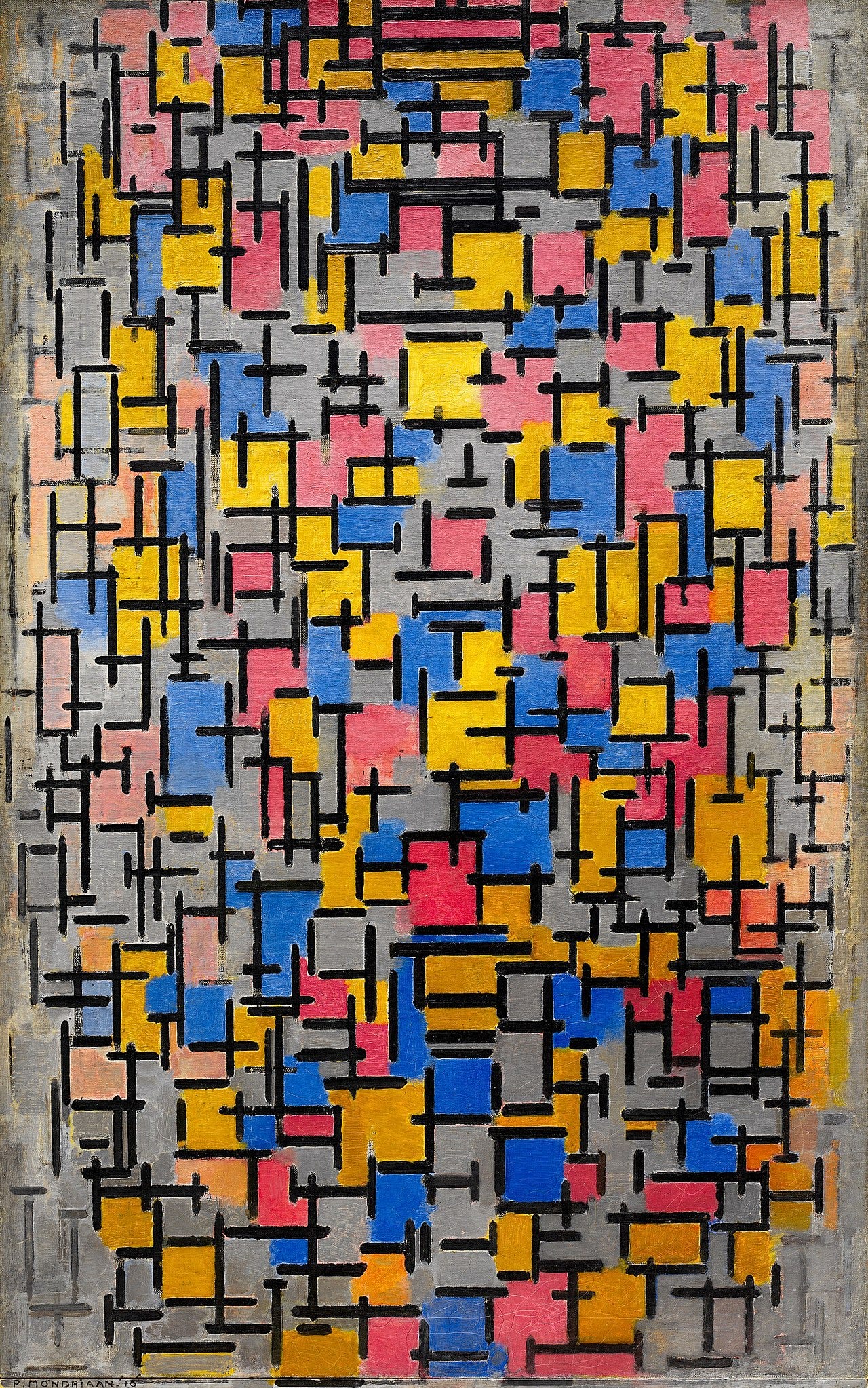

His trees provide a great study of Mondrian’s very gradual movement towards geometric grids.

Then he apparently gave up on giving the paintings the name of concrete things, and just went with “Composition”.

Except for the occasional landscape painting of a farm or windmill, and a couple of portraits, he would just keep making those for the rest of his life.

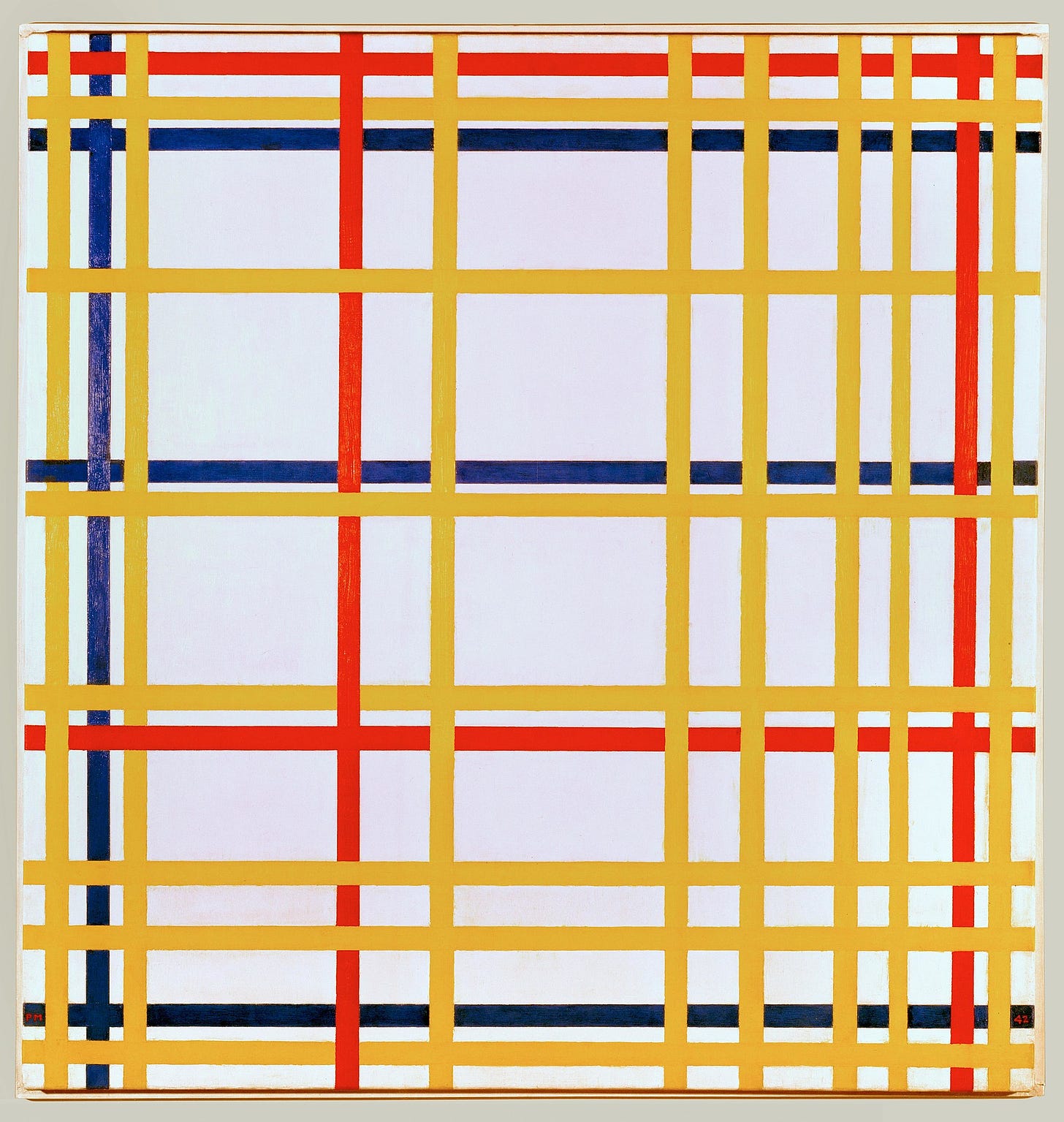

Culminating with his last few pieces, considered to be some of his best: Victory Boogie-Woogie and New York City.

A much longer list can be found here. (There’s also this thread, which provided the initial inspiration from this post.)

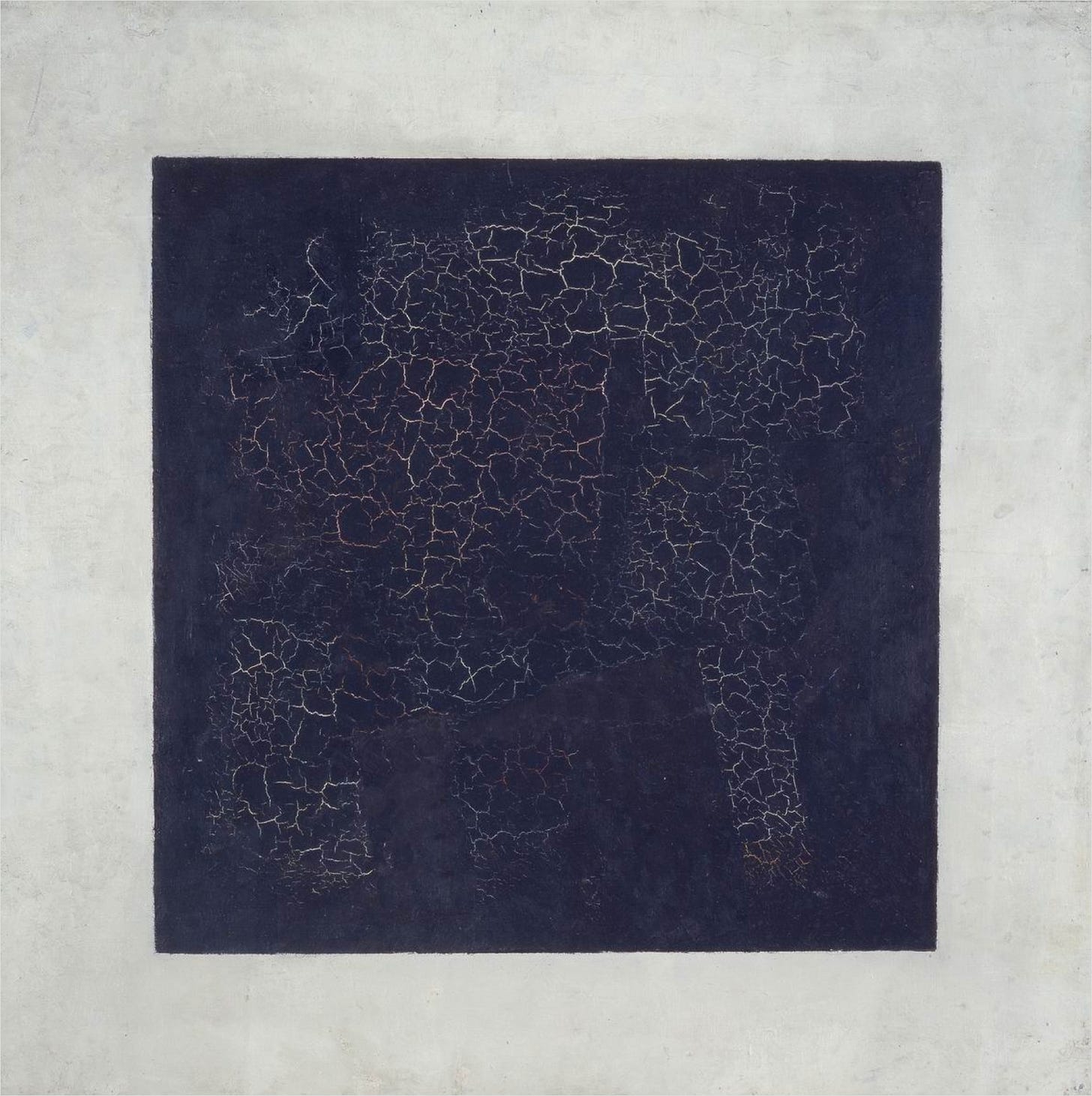

III. Malevich

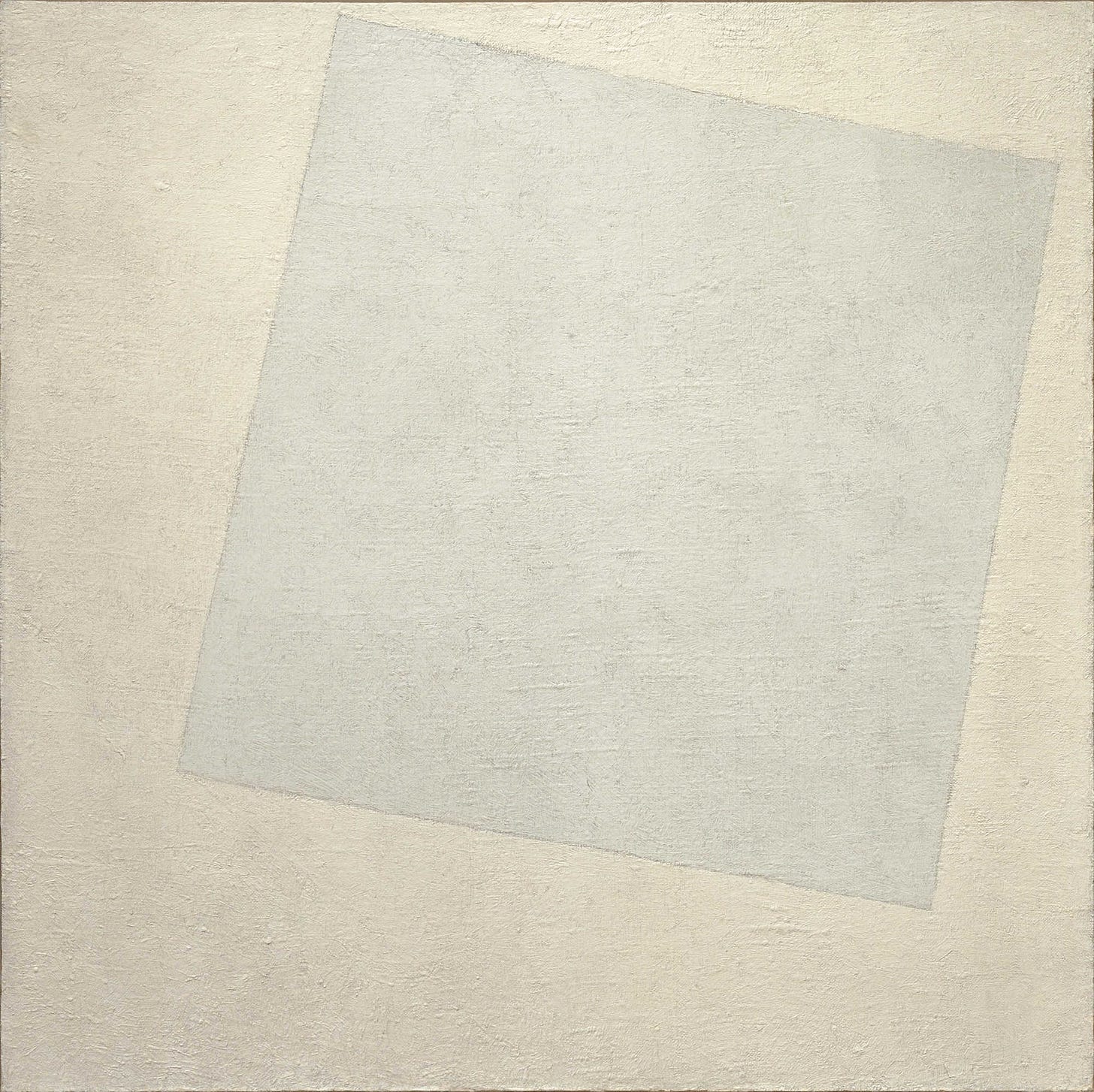

Kazimir Malevich, a Polish/Ukrainian/Russian avant-garde artist, is perhaps the worst offender to the abstract art non-believer. His most famous painting is titled Black Square and, well, looks like this:

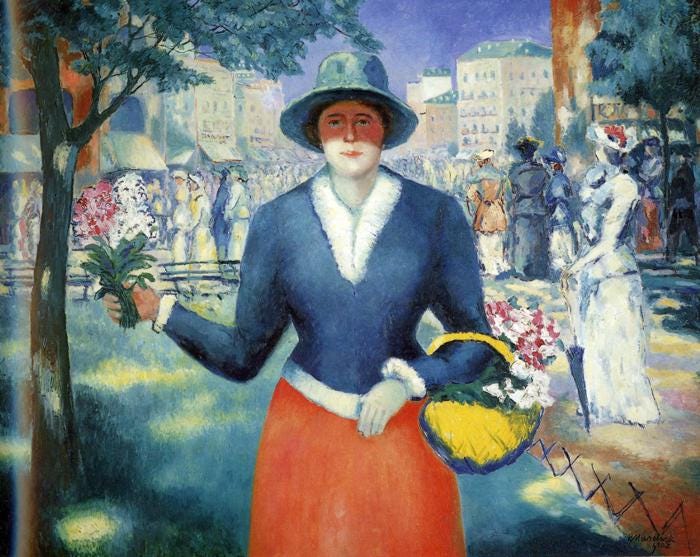

Surely Malevich was a fraud who was just well-acquainted with art appraisers from the Russian Empire and/or the Soviet Union? Surely he couldn’t paint a picture of a stunningly beautiful girl selling flowers?

Okay I may have exaggerated a bit with “stunningly beautiful.” But still, the man could draw.

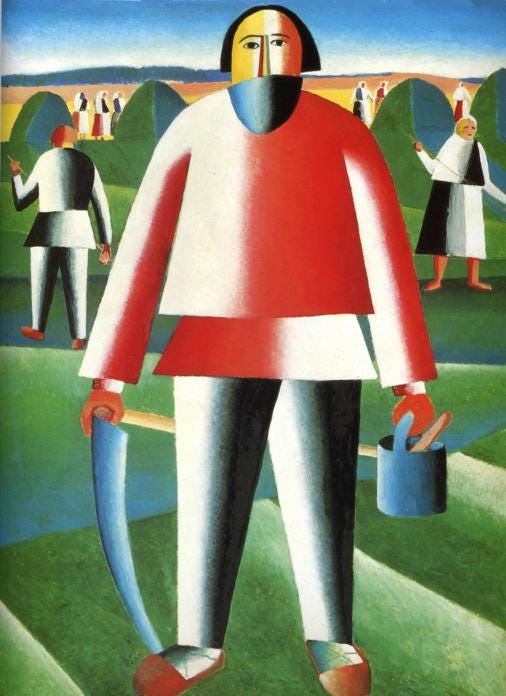

Unlike the above two artists, Malevich didn’t linearly move from figurative to abstract art: he still produced plenty of representational works in his later career, like this one:

We can still spot a trend. Around 1906, he made a bunch of landscapes that seem abstract from up close but make sense when you look from a distance:

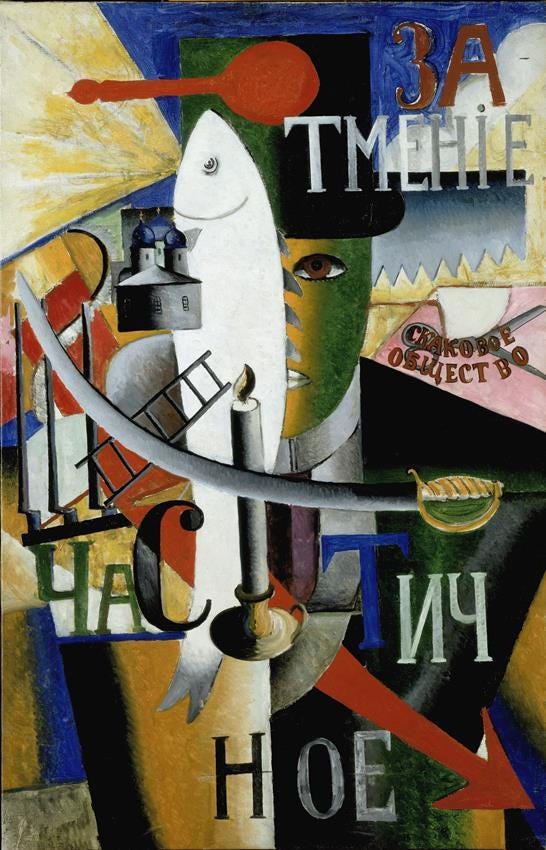

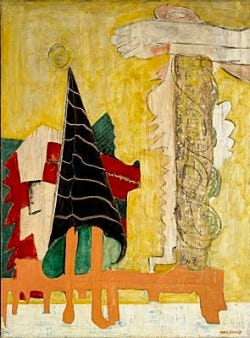

Then, in the 1911-1914 period, his art tended to look like this:

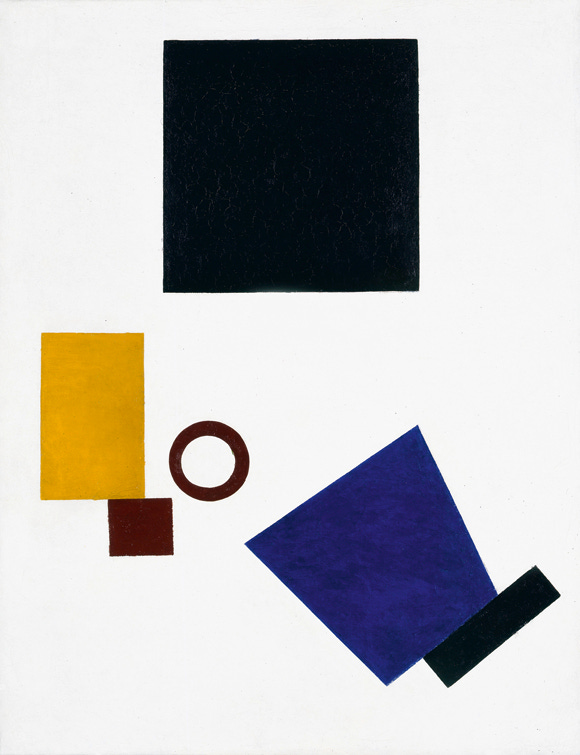

From where it’s not totally surprising he moved on to the fully abstract genre he called “suprematism,” which includes Black Square and many other pieces such as the sample below.

Abstract art skeptics love to ridicule pieces like White on White which may seem pretty dumb at first glance, but I don’t know, looking at the full Malevich catalog, I think they make sense. Sure, if he had only made those, nobody would know Malevich’s name. But an artwork’s value comes from more than just the technical skill necessary to make it, and that includes the story behind it, as well as the intangible compositional and color choices that come from a lifetime of painting, and both of these do confer value to Black Square or White on White.

IV. Pollock

Okay, I lied, neither Mondrian nor Malevich is the archenemy of the abstract art non-believer; that title belongs to Jackson Pollock.

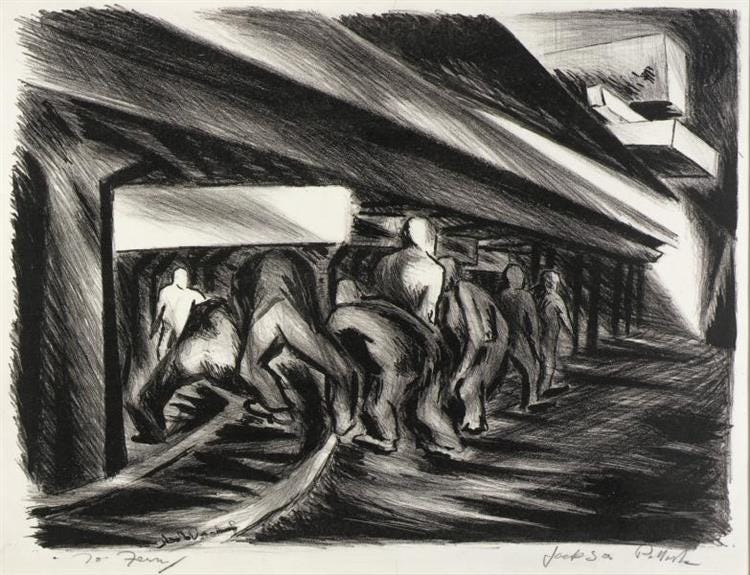

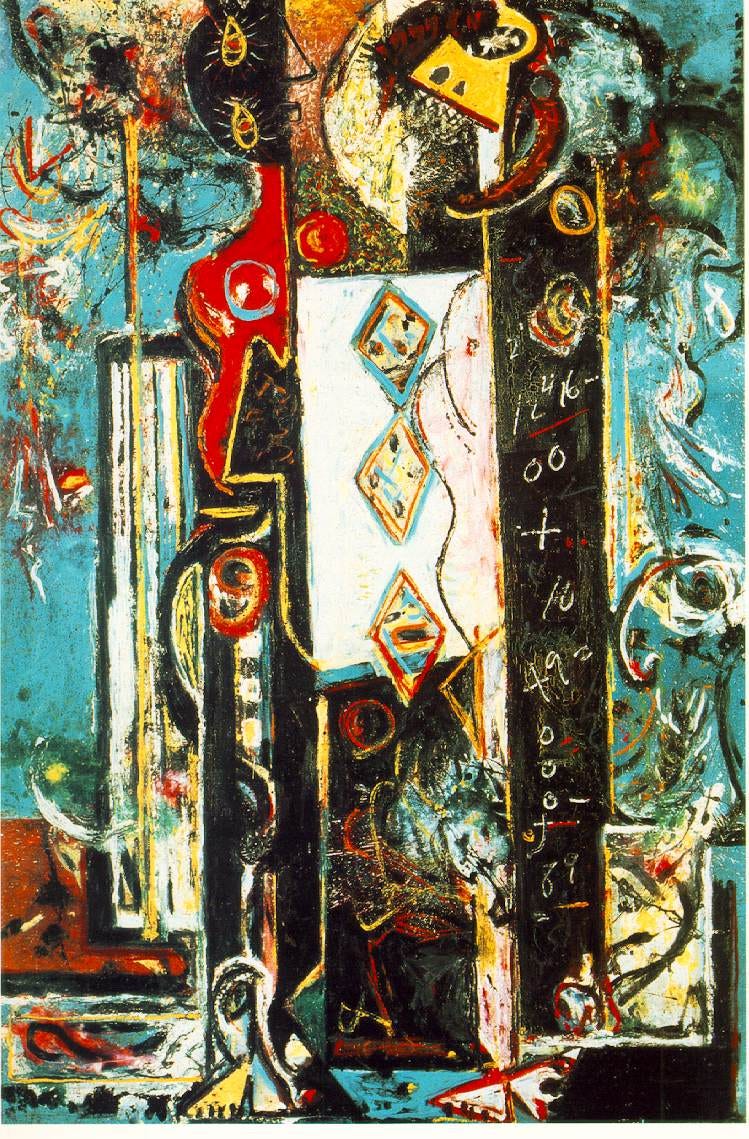

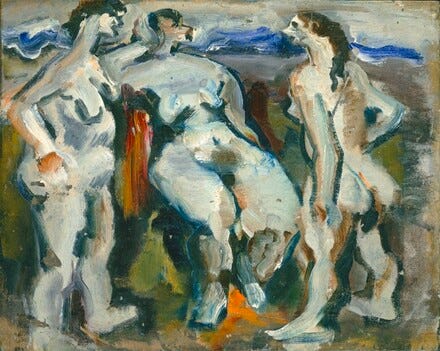

The observant minds among you might have noticed the Pollock was quite younger than the other artists we’ve seen so far: he was born in 1912, a full 40 years after Mondrian, for instance. His career began in 1936, well after abstract art was established as a credible genre. Perhaps that’s why we don’t see that much early Pollock in classical figurative styles: his inspiration could already come from existing modern art.

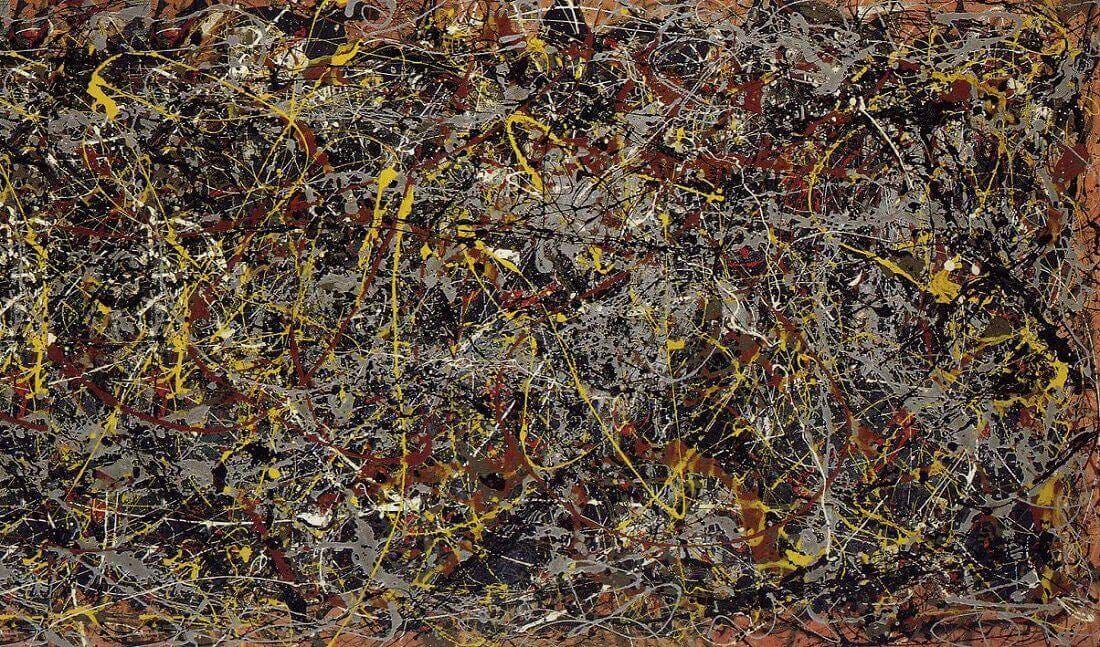

That doesn’t mean that he only produced “drip” paintings like Number 5.

His paintings certainly are surrealist. But I contend that they do show a level of artistry that we wouldn’t see if Pollock were a fraud who’d somehow figured out a way to get both fame and fortune by randomly dripping paint on a canvas.

V. Rothko

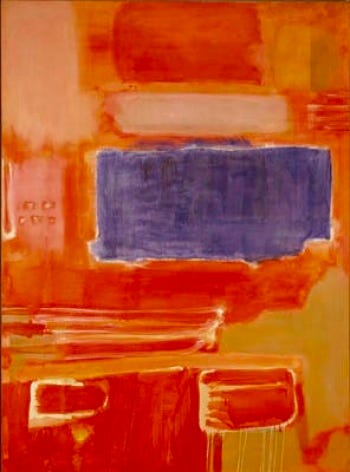

When I visited San Francisco last spring, I went to the SF Museum of Modern Art and saw a Rothko. It’s this one:

It has been said that the true power of a Rothko can only be witnessed in person. On a computer screen, or in a book, a Rothko will look like a simplistic juxtaposition of two colors. In person, it fills your field of vision and your soul, and you can stare at it for a long time, totally absorbed.

I didn’t undergo any kind of spiritual transformation in the SF MoMA. But I did enjoy gazing at for some while.

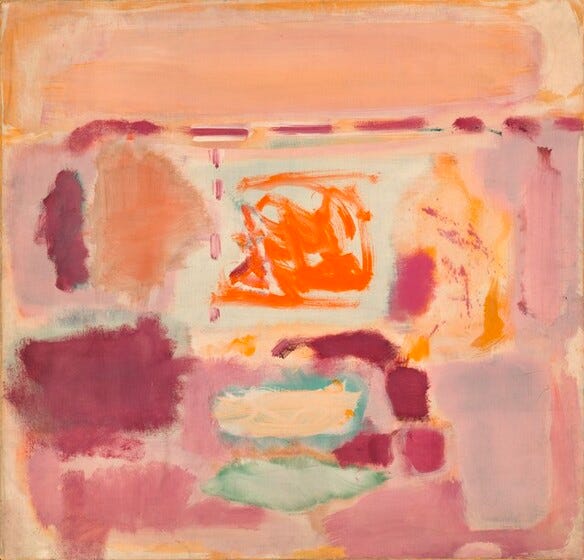

Mark Rothko’s signature color compositions were a product of the two last decades of his life — the 1950s and 1960s. But he started painting in the 1930s, and the progression is nicely visible:

Hopefully making that last one the largest size Substack allows gave you a glimpse of the overwhelming sense Rothko paintings can create. For more, this page (early works) and the this one (classic works) provide a good overview of Mark Rothko’s oeuvre.

The pattern I’ve exemplified five times (six if you count Picasso) is quite common. I looked up several other abstract artists from the early 20th century, and it’s basically always the same story. Willem de Kooning, Robert Delaunay, Hilma af Klint… Basically every abstract art pioneer was first trained as a classical artist making landscapes and portraits and still lifes, and only later decided to explore the art of composing pure shapes and colors.

This may not hold for recent, contemporary artists, however. Abstract modern art is now well over 100 years old, so it’s presumably quite common for aspiring painters to draw most of their inspiration from it and start with shapes and colors rather than human bodies and windmills. I would hesitate to make a strong claim, but I’m sympathetic to the idea that this might be a mistake. The best abstract art may come from distilling a few subtle aesthetic properties that become apparent only after a lifetime of drawing representational pictures.

If that’s true, then abstract art non-believers may (partially) have a point: it’s entirely possible that a lot of abstract contemporary art is frankly not great, because it tries to imitate Picasso’s pure linear bull without going through the intermediary bovines. And sometimes the imitation might fool people who want to be seen as sophisticated, and be valued much higher than it should be based on its actual aesthetics.

But I doubt that’s happening much, to be honest. To be sure, there’s a lot of crappy contemporary abstract art (just like there’s a lot of crappy anything), but the best abstract art actually teases out interesting aesthetic properties and is therefore actually good.

(For people who have a taste for it, at least. It’s fine if abstract art isn’t your thing, as long as you don’t turn that into some kind of pronouncement that abstract art shouldn’t be anyone’s thing.)

On the other hand, all my examples are from the 1900 to 1950 period, a time of great change in art due in part to great technological and social progress. So maybe it’s expected that the pioneers of abstract art had to start from classic painting. Maybe the figurative-to-abstract pipeline is specific to that time, and doesn’t really apply now — and artists can do whatever they want, including being untalented yet well-connected, drawing a black line on a black canvas, and selling that for 5 million dollars if they can get away with it.

I guess I just don’t think they can get away with it. Not without actually showing us something really interesting, which is their job as artists. One that Picasso, Kandinsky, Mondrian, Malevich, Pollock, and Rothko actually managed to do admirably, thanks to their long experience, great talent, and desire to push the boundaries of Western painting further than it had ever been.

>it’s entirely possible that a lot of abstract contemporary art is frankly not great, because it tries to imitate Picasso’s pure linear bull without going through the intermediary bovines.

>but the best abstract art actually teases out interesting aesthetic properties and is therefore actually good.

I'm going to assume, from these two sentences, that you consider the bull to be great abstract art. But I disagree with that assessment: the bull is not just reduced to a pure linear form, it's reduced to a vague linear form. It could be a number of horned quadrupedes, with no distinctive feature. Information is lost, rather than drawn down to it's essence.

I also contest that "The people claiming these things usually don’t have a lot of knowledge about art history". As you show in the devolution of various artists, one can see abstract art as a kind of navel gazing, where the artists starts mistaking the mean of it's art with it's purpose. It's not a behaviour limited to painting either. Some theater playwright, feeling there's no more point of doing yet one more play with dialogues, characters, story or costumes, will have actors silently perform meaningless movements naked on scene for 2 hours and a half. Some programmers, bored with usefuls programming languages, will start conceiving & toying with things that read like "++++++++[>++++[>++>+++>+++>+<<<<-]>+>+>->>+[<]<-]>>.>---.+++++++..+++.>>.<-.<.+++.------.--------.>>+.>++."

I can understand why/how some people, after reaching a degree of mastery of a given field, start substituting the means to the end, and researching ever-increasing mastery of said means. But I refuse to pretend it's anything but meaningless navel gazing, or that it should be encouraged.

And finally there's also a personal, and a bit childish, dislike for the unfalsifiability of abstract art. As I was looking at an exposition with a friend who enjoy these much more than I do, all he could give, on pieces he liked, was "I like the vibe it gives". Which is probably the best way to enjoy it, relying on pure gut feeling. It also means there's no bad abstract art. For any drivel produced, hey, maybe there's someone out there that will see it and go "oh yeah that's a good feel". And if there's no bad abstract art, is there good abstract art?

I loved this post! The irrational anger that some people feel about abstract art has always struck me as a sign of a lack of empathy and imagination. Abstract art isn't everyone's thing, no big deal. But the absolute venom some people have towards it is a red flag to me.