Why Do I Feel Inadequate at Coming Up With Research Ideas?

And an attempt to anoint myself as an Asker of Questions 🙋

The other day a friend asked me the most anxiety-inducing question. It wasn’t their fault — there was no particular reason for them to guess I was sensitive to the question, on the contrary. We were talking about large language models (AI programs that can generate credible text, like ChatGPT), which is a topic we’re both interested in, and they asked me: “What interesting research questions do you have about language models?”

My face fell. I drew a blank. Instead of coming up with cool research ideas, a part of my brain generated nice thoughts such as “OMG I’m such a failure this is the topic I chose to focus on and I work with these things on a daily basis and yet I don’t have anything interesting to say or even ask how am I ever going to have an interesting career in this field oh god oh god oh god” while another part of my brain reminisced about countless similar occurrences during my time as a science student, when I just latched onto research proposals made by professors because I couldn’t come up with my own.

I told my friend I felt unusually bad at research questions, and they were surprised: “But you write such cool blog posts!” they said. Thanks, friend, but even assuming that’s true, it actually highlights the inadequacy even more! Clearly I’m a decently intelligent human being who’s able to say interesting things sometimes, so why do I still feel utterly inadequate at coming up with interesting research ideas?

This is a post to explore the question and perhaps, in the process, cure myself of that inadequacy. This matters to me because I'd like this blog to contain more research posts, and because I believe my career will be more interesting if I do more research. It probably matters more broadly too because I suspect that we'd be better if we were all collectively better at research, whether professionally or not.

First, let's examine some hypotheses, and then we’ll try a solution.

Hypothesis 0: I'm not actually interested in the topic

This is the null hypothesis. As is probably quite obvious, coming up with research questions is difficult when you don't give a fuck about a topic. This explains most instances of me not coming up with research questions (for instance, I don't care about soccer/football, so I have no cool questions to ask about it), but it doesn't explain the general case, where I am interested in some topics and feel inadequate nonetheless.

Hypothesis 1: Research is inherently hard

This hypothesis feels like a cop-out, but I think it’s true: research is an inherently difficult activity. It’s at least on par with other creative work, like art and business and blog writing. None of these are, like, playing on hell mode or whatever, and millions of people are able to succeed at them — but by definition, they involve doing things that no one has done before in quite the same way, which is kinda hard. Certainly harder than being told what to do.

But research might also be slightly more difficult than art/business/writing, at least in some sense. You can be a decent artist just by coming up with a moderately creative idea and then impressing everyone with your art skills. You can be a decent business owner by flatly copying someone else’s business but targeting a different market. You can be a decent blogger just by writing about old ideas in some refreshing way (just look at my work!).

In research, no one is impressed when you answer a question that’s already been answered. Research often feels… more universal, even at the amateur level. Even if you do come up with a cool research idea, if someone’s already done it, then there’s no reason to pursue it, whereas in art/business/writing it might still be worth doing that.

Still — I know for a fact that finding ideas for writing gets easier with practice. Surely research questions are a similar skill that can be developed. So why am I still bad at it, after years of studying science and writing blog posts?

Hypothesis 2: There’s no reward, or maybe there’s a negative reward, for uninteresting research

When a kid draws an absolutely ugly picture in which the sky is an unrealistic blue line at the top, everyone is delighted. When a kid constantly asks “why? why? why?” about stuff, everyone is annoyed.

In theory, everyone recognizes that curiosity is good, but in practice, curiosity is often discouraged, and I’m not just talking about kids. Of course, when curiosity does lead to some new insight, people will congratulate you, as they should. But when your curiosity leads nowhere, people will say you’ve been wasting your time. When your curiosity is unoriginal, people will tell you that your question has already been answered (just google it! just read this or that book!), and therefore you’re wasting your time. When you’re a grad student in a field that your parents don’t understand and doesn’t obviously lead to good jobs, your parents won’t tell you directly, but they’ll secretly think that you’re wasting your time.

And the problem is, they’re often right! It is a waste of time to ask bad — i.e., uninteresting — research questions, which is definitely most questions you’ll ask, at least initially.

The one way it is not a waste of time is in providing practice, which is why we congratulate bad art by aspiring artists, and bad blog posts by aspiring writers: we know they’ll get better eventually, and often their beginner-level work is still interesting in some way, at least to them. For research, we don’t seem to realize the value of encouragement to the same degree, and bad questions aren't rewarding to anyone involved, least of all the rookie researcher himself. And so the skill never develops, unless you’re trapped in a PhD program and have no choice.

(Maybe that's the entire value proposition of a PhD program, come to think of it. Sequester you for 5 years and until you can come up with good research questions!)

Hypothesis 3: All fields are complicated and induce the impostor syndrome

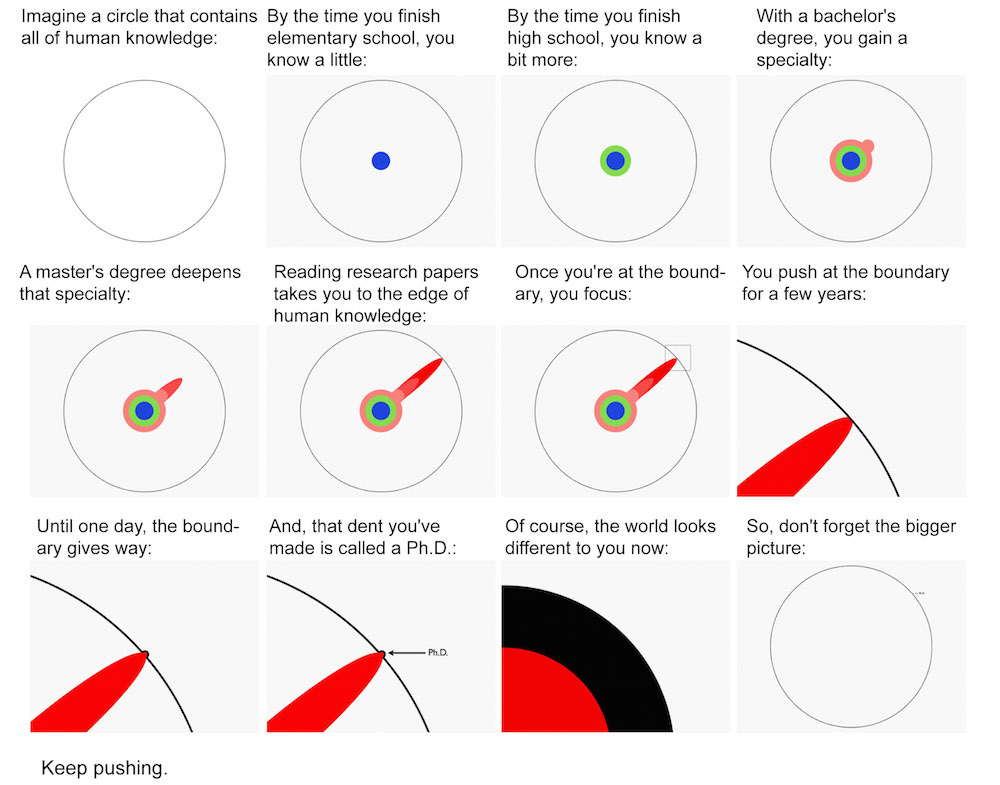

Compounding the inherent difficulty of research, and its lack of reward for beginner work, is the fact that research in general doesn’t exist: it's always research in a highly specialized field that takes years to learn.

To be clear, that's not strictly true. Sometimes a new field opens up, with a lot of low hanging fruit that even amateurs can pick. Besides, we can ask general questions if we want, nothing’s stopping us. But most of the time, high-quality questions are necessarily very niche and impossible to come up with without a deep understanding of a field.

Which means that unless you can credibly believe that you're a top expert in your field, you’re bound to think that there are more competent researchers out there, who are far more likely than you are to ask good research questions. Until you've read dozens of books and papers on the topic, and talked to the current top experts, there’s no point in coming up with questions of your own. Anything you could ask is almost certainly not cutting edge, and therefore already answered. Right?

Yes and no. Or rather, yes, but you should believe no. The problem is that often, even when you do have the requisite knowledge to ask good questions, you might not realize it, because you’re not literally the top person in the field. Or because you imagine a theoretically better person than yourself, even if you actually are the top person in some specialized field!

This is an instance of the impostor syndrome, a dumb psychological phenomenon that as far as I can tell affects nearly everybody to some extent. The way to defeat the impostor syndrome is to lean in and just accept to play the impostor part, which everyone else is doing anyway. But that feels wrong, so in practice I don't ask good research questions in any of the many fields I'm interested in at an amateur level.

Hypothesis 4: I hate feeling stupid

I used to be a perfectionist. School was easy for me, so success seemed like the default. But as anyone with a decent understanding of science and research knows, failure is much more common. It’s in fact absolutely normal even for genius scientists, like Niels Bohr or Richard Feynman, to feel stupid:

To a large extent, your skill as a researcher comes down to how well you understand how dumb you are, which is always “very”. Once you realize how stupid you are, you can start to make progress.

Yet good research questions depends directly on being smart! There’s a tension here, and it’s particularly difficult to navigate for those who see their own intelligence an an important part of their identity. Regrettably, that’s a good description of myself. It used to, at least. I’m getting used to feeling stupid, because I know it’s good to be comfortable with that, but I’m not fully there yet.

This hypothesis feels wrong in at least one way: I definitely felt stupid when I wasn’t able to come up with good questions about large language models in that discussion with my friend. It would be pretty ridiculous if the fear of feeling stupid in one context led to feeling stupid anyway in some other context, but I guess that’s actually rather plausible.

These hypotheses help understand the problem, but they don’t provide solutions. How can I dispel the feeling of inadequacy? How can I generate quality research questions?

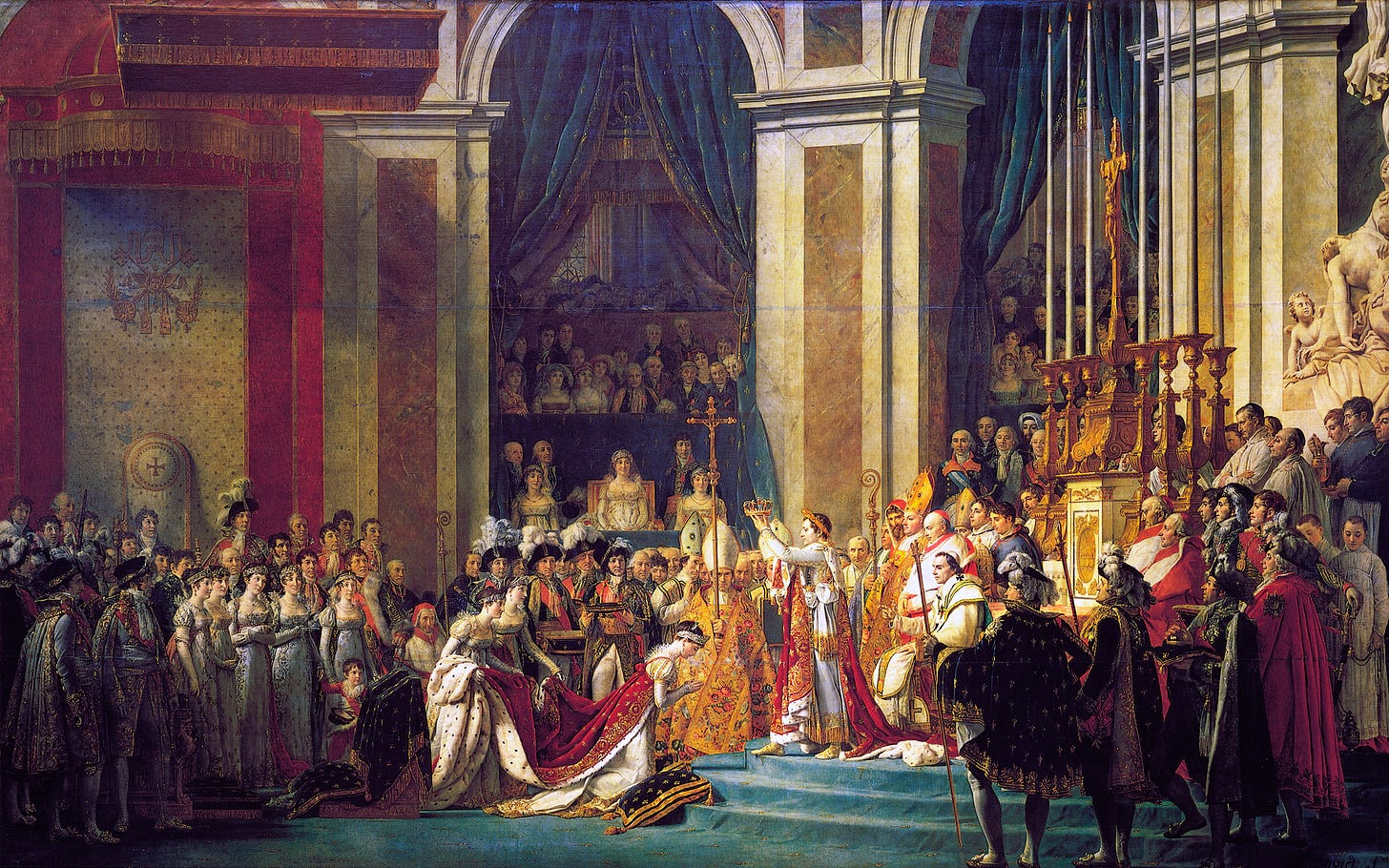

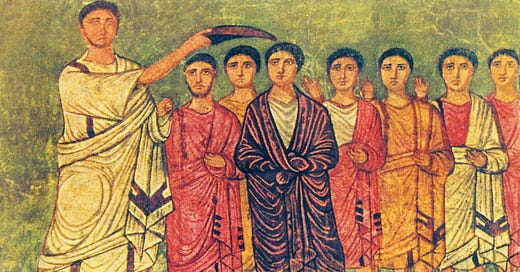

My friend said something interesting: they said that we often feel like we must be “anointed” as someone who can work in a field. Anointment — pouring ritual oil on someone to mark them as a king or something — is a symbolic gesture, but symbols often matter enormously. A graduate degree from a university can serve this purpose: regardless of how good of a researcher you are, you’re a PhD now, which means you are Allowed To Ask Questions.

But it’s entirely possible to imitate Napoleon Bonaparte and anoint ourselves. The thing is, it has to be hard in some way. I felt like an impostor “writer” for a long time, and then I wrote 100 blog posts over two years, and now I feel like a legit writer. I am Allowed To Write Blog Posts.

(Interestingly, my friend, though they don’t have a problem with asking research questions, feels inadequate at writing blog posts. This is a class of problem in which, annoyingly, solving one instance of the problem doesn’t automatically solve the others.)

So in the spirit of pouring oil on my own head, let’s do some practice. Let’s ask a bunch of stupid, low quality research questions about large language models. I’ll make it unserious by avoiding capital letters, good syntax, etc. Don’t feel like you need to read it; you can consider the post to end here. (although hi i’m here from the future to say that the question practice ended up being fun and i think its worth reading after all!!)

To be honest, I’m legitimately scared of doing this, especially publicly. But I’ll do it anyway, though I might scream with anxiety and terror along the way.

question practice aaaah

can we use gpt-3 to

okay i actually had to stop here yesterday because i just couldn’t do it. it is now the next morning, and i don’t know if i’ll be able to do this aaaaaaaah

can we use gpt-3/chatgpt to generate good research questions

lol i guess it makes sense that this is the first question is about this. after all, the best research questions are those that look for solutions to problem you currently have!

this suggests a way to cheat. what if i ask chatgpt about LLM research questions?

Sure! Here are a few research questions that could be explored when working with large language models:

How can we improve the efficiency of large language models, both in terms of training time and inference time?

How can we make large language models more robust and less prone to adversarial attacks?

How can we incorporate domain knowledge or external sources of information into large language models to improve their performance on specific tasks?

How do large language models generalize to unseen data and how can we measure their generalization ability?

How can we better understand the internal representations and decision-making processes of large language models?

How can we use large language models to improve natural language understanding and generation tasks such as translation, summarization, and dialogue?

How can we use large language models to improve other tasks such as vision and speech recognition?

How can we ensure that large language models are ethical and fair in their predictions and decisions?

that definitely feels like cheating, but actually there are no rules to this game, so whatevs. these questions feel pretty general, which is good: they’re not immediately actionable, but they provide useful directions.

lets try to go further in some of these!

can LLMs ever be trustable regarding how much bullshit they generate?

would it be possible to use LLMs to do their own error correction, like finetune a model to detect errors in the output of another model?

but then how can we trust the error-correction model???

can we make text-to-image models able to generate good text in their image? like combine LLMs with image generation in some new way, so theyre automatically able to deal with text even when not in text format

do generalize LLM / text recognition! an ai that can just read whatever text in whatever visual format and respond to it

i know (because it’s relevant to my job) that we can compose calls to LLMs to do useful things. composing means generating an output and using it as input to generate a second output, and so on, to achieve a complex task

could we generalize this

can we make an equivalent to a programming language that’s built entirely out of english?

speaking of english, are there cool things to try in other languages that people may have been neglecting?

machine translation is an obvious application… hey, what about using chatgpt to translate “untranslatable” words from other languages such as dépaysement or schadenfreude?

okay i tried this now and got a few cool ones:

dépaysement: fremdness (from German “fremd” meaning foreign/strange), unfamiliaritude

schadenfreude: maliciousglee, maliciousmirth, spitefulglee, or my favorite, misfortunemerriment

hygge: comfortitude, warmthiness

komorebi (木漏れ日): leafshine, treelight, branchdapple, leafshimmer

can we easily construct artificial languages for movies, games etc that sound credible, are grammatically consistent, and don’t resemble existing languages too closely?

okay i also tried this and the results aren’t great lol. this is supposed to be a constructed language that sounds like french and japanese but isn’t related to either (and certainly not related to english):

"Thae solae glaemz through the lufz of the arbez, crating a sift komorubi."

seems like, for now, linguists who create conlangs are safe from automation!

looks like ive got a good rhythm going! as expected this is getting easier with practice, like most things

let’s think about science a bit more, which is a field im quite interested in

LLMs can definitely help with science e.g with brainstorming questions, and writing up the results, but can they automate other steps?

could they, with access to internet, generate hypotheses and actually test them

i guess a challenge would be to make it, uh, ask good research questions … you don’t want to test thousands of stupid hypotheses

or maybe you do??

also i guess there are chances of doing unethical science, someone should look into it

can LLMs help with fixing the horrible state of science publishing

could we generate super-standardized IMRaD papers super easily but also not expect anyone to read them, they’d just be an archive

also LLMs could be trained to extract the results of those super-standardized papers easily

and then scientists can actually focus on writing good, interesting articles to actually make their science fun and attractive

what are the limits, if any, to finetuning?

will some tasks always be outside the reach of LLMs no matter how much theyre trained?

can we test that? prove it mathematically?

are there things for which there just isn’t enough data in the world?

can we artificially generate that data? just like dreams are extra fake data for humans

can LLMs dream? should we implement dreaming to reduce overfit?

how cool would it be to say that we’ve made machines dream?

… And I’ll stop there, because this is getting long, and also — I think it helped? It almost feels silly now to think about the rest of this article, since… this wasn’t actually hard, once I started in earnest. I don’t know if any of my questions are cutting edge, but some are cool research directions, I think. I tweeted the untranslatable word neologisms 15 minutes ago and it already has a bunch of retweets, which is a sign that others find it interesting.

It seems like all I need to do, now, is to practice some more — and then I’ll feel I’ve anointed myself as an Asker of Research Questions, with capital letters. And then I can kiss goodbye to the anxiety of feeling like a stupid impostor whenever people ask me if I have research ideas.

Alternative Hypothesis: loneliness destroys innovation. If you don't have a bestie to talk about your research, having an "AI companion" does help with reducing friction. Ultimately collaboration has other parts of research that no AI interaction can bare, including emotional support and one and a while "lover's quarrel".

P.S. the news of Replika's AI progressing towards erotic behavior implies academically oriented AI will regress towards uninspiring "paper mill" behavior when left unattended.

"This wasn't actually hard, once I started in earnest" - as a terminal procrastinator, I find the same thing. Inevitably, once I finally just sit down and START, it's much easier than I expected. You'd think that after enough instances I'd internalize this enough that it would lower the getting-started barrier, but alas, no such luck.

"will some tasks always be outside the reach of LLMs no matter how much they're trained" - this is the question I'm most interested in. I think it may be linked to the bullshit-detecting question. I'm certainly no expert, but my intuition is that current LLMs (and other ML models) are exceedingly effective pattern-generalizers. We've figured out a way to, after exposing the machine to enough examples of patterns, somehow encode the common basis of those patterns into the network such that we can then turn it around and get it to produce more patterns. The problem is, at this point that's all they are - patterns. There's no distinction between "real" and "not-real" the way that humans (usually) have. Hence why ChatGPT will happily produce a blogpost about how scented candles can stop WiFi sniffing attacks: https://twitter.com/benedictevans/status/1601035547900018688

It's possible that this limitation could be overcome, but I think it will take more than just "bigger models." Maybe someone can combine a LLM with some sort of "memory", just a big database facts, and it can use that as a starting point instead of trying to generate its patterns from whole cloth, or something like that.