One Thousand and One Notes on ‘One Thousand and One Nights’

Genies, plot holes, dumb people, and perseverance 🧞♂️

I.

Scott Alexander, master of the book review genre, once wrote about the Arabian Nights. He published his review during the 2021 edition of his book review contest. It was a masterclass. Many people hadn’t realized it wasn’t an entry by a contestant, and were certain he would win. (He eventually did enter his own contest, this year — and yes, he did win, though he then disqualified himself, allowing me to win third place with a review of Jane Jacobs’s works.)

I liked the Arabian Nights review so much that I decided to read the tales myself. It helped that random chance, as for the Jane Jacobs books, had made some of the books land in the public box next to my house. It is amusing just how much of my intellectual life depends on that one book box.

II.

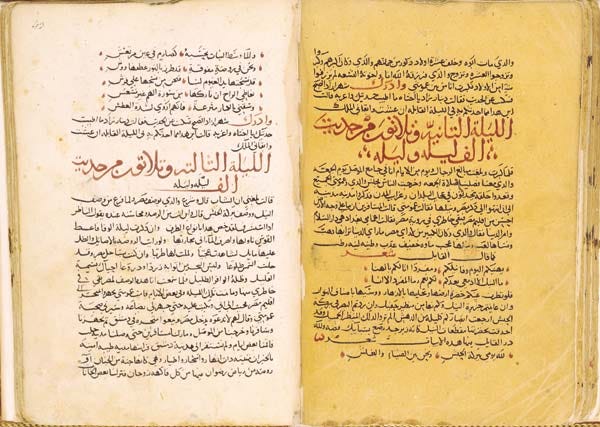

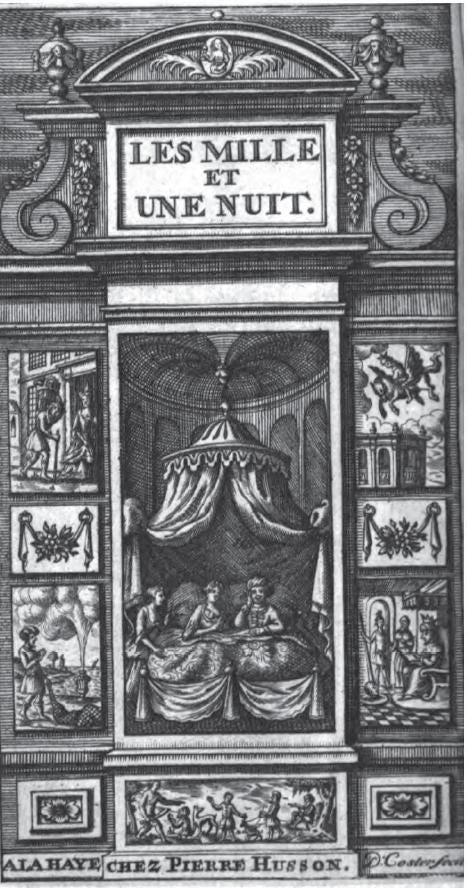

There are many versions of One Thousand and One Nights. The one reviewed by Scott was an abridged edition of Richard Burton’s translation, made during the Victorian era with all the biases that the Victorian era implies. The one I read was in French, and was in fact the first published edition ever — the collection made by the orientalist and translator Antoine Galland between 1704 and 1717, around the end of the reign of Louis XIV. With all the biases that the Louis XIV era implies.

III.

I haven’t read the Burton version, but it is known that there are significant differences. For one thing, Galland’s translation was based mostly on a manuscript from Syria, with additional tales from other manuscripts (such as “Sindbad the Sailor”) as well as some that were told to Galland by a Syrian traveller (more on that later). Burton instead based his translation on Egyptian manuscripts, which were compiled later and contain more tales, and longer ones too. There is only a small core of tales that are common to both. It’s unclear which of them is more ‘authentic,’ whatever that might mean.

IV.

Scott Alexander writes that Arabian Nights is, “most of all, … a book about how your wife is cheating on you with a black man.” I am sorry to report that Galland’s version does not feature that much interracial cuckoldry. For example, in the story of Beder, which occurs both in the Syrian manuscript and Galland’s translation, there’s a witch-queen who turns black men into birds, and then turns herself into a bird to have sex with them. However, that specific episode — the contents of Night 265 — was skipped by Galland, most likely to avoid hurting the sensibilities of his readership.

In any case, it seems that the original folk tales contained quite a few erotic or naughty passages; Galland deemphasized or censored most of them, while Burton, 175 years later, added some extra spice for the benefits of his sex-obsessed Victorian kinsmen.

There is still some interracial adultery, in case you were wondering, including in the main story. Clearly that was a real concern in whichever part of the Middle East or South Asia the tales came from.

V.

Galland also removed all of the poetry. I won’t complain; I tend to just skip poems and songs that are inserted into fiction.

For that reason, and also because he thought his readers would get bored, he skipped Nights 101 and 102, which “are employed in the original to the description of seven robes and seven sets of jewelry.” Maybe more translators should elect to just leave out the boring bits.

VI.

The frame story — the story that contains all the other stories — is famous enough, but it’s worth retelling it briefly.

King Schahriar was reigning over the Persian Empire, which had been extended by his father “into India, in the large and small islands that are attached to it, and quite far beyond the Ganges, all the way to China.”1 His younger brother, King Schahzenan, hadn’t inherited anything, but he and Schahriar were so close that Schahriar gave him a part of his empire, the Kingdom of Great Tartary — i.e. Central Asia, with Samarkand as the capital. After ten years, Schahzenan decides to visit Schahriar in India. He bids farewell to his wife the queen, and then leaves Samarkand, but camps just outside the city before the real departure. He decides to go see his wife one last time because he loves her very much. But lo! She is in bed with another man (race unspecified). Angry, Schahzenan kills them both and then leaves for India.

In the Indian capital, Schahriar notices that his brother is unhappy, and asks why; but Schahzenan prefers not to talk about it. Schahriar invites him on a hunting trip, but Schahzenan is too forlorn to go, so he stays behind in the palace. During that time he witnesses an extraordinary thing: Schahriar’s wife, thinking that the two kings are away, organizes an orgy in the palace courtyard. Eleven black men and eleven palace women, including the queen, spend the entire evening doing something that “decency does not allow us to tell” right under Schahzenan’s eyes.

Schahzenan’s sadness is dispelled: clearly all women are equally terrible if his brother, the king of the greatest empire in the world, gets the same treatment as he did. Upon his return, Schahriar is pleasantly surprised that his brother looks happier, but he wants to know why. Schahzenan prefers not to say; but Schahriar insists and Schahzenan eventually tells him everything. At first, Schahriar doesn’t want to believe his wife is cheating on him with several black men, but he agrees to schedule another hunt, while secretly staying behind as a stratagem to discover the truth.

Sure enough, the queen organizes another orgy with eleven black men an equal number of palace women. Schahriar is dismayed, and he and his brother conclude that they should abandon their respective kingdoms and travel the world.

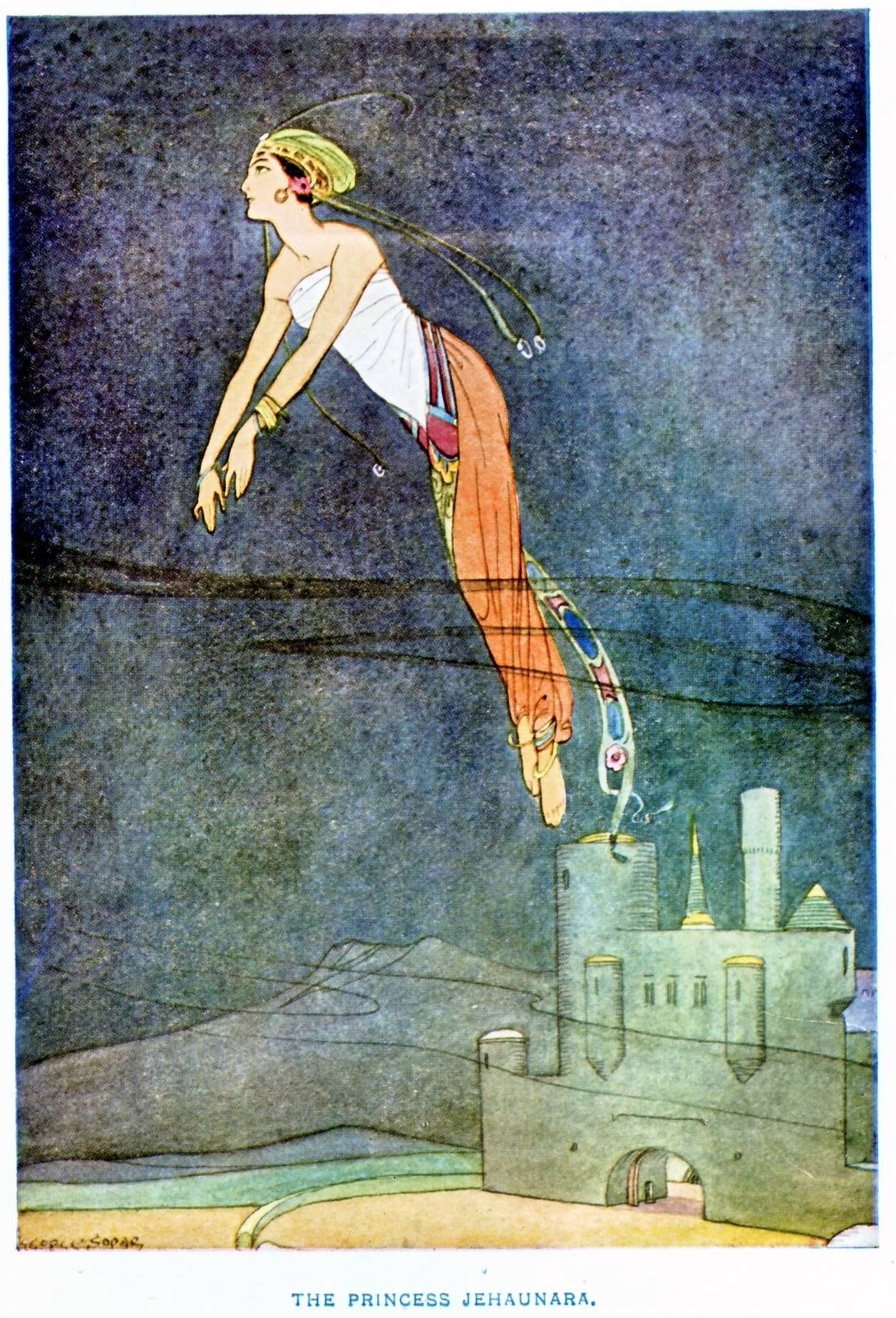

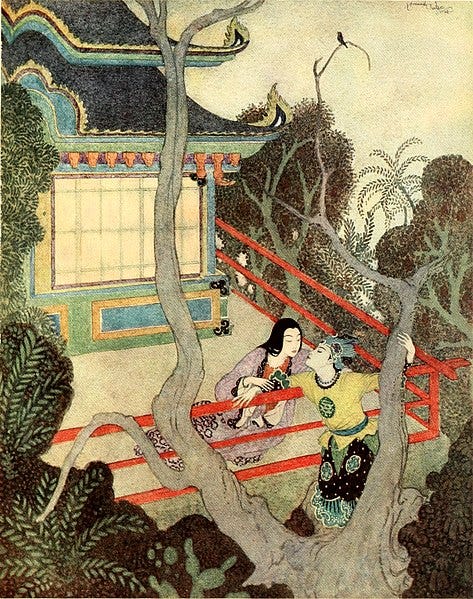

During these peregrinations, they witness a mighty genie who lets a beautiful woman out of a box (see the image at the top of this post). After the genie falls asleep, the woman notices the two kings and asks them to make love to her, otherwise she’ll ask the genie to kill them. It turns out they’re lovers #99 and #100 — she had been on a project to sleep with 100 men right under the genie’s nose. After this episode of not-quite-consensual sex, Schahriar and Schahzenan realize that the genie, despite being more powerful than men, is even more of a cuckold than they are. Having found that they are not, in fact, the unhappiest representatives of the male sex, they go back to their respective kingdoms.

Schahriar has his wife killed, and then he decides to marry a new girl every night and have her strangled the next morning. Everybody in the Persian Empire recognizes this policy as totally insane, especially the great vizier who is tasked with finding a new woman every day. It ends up being the great vizier’s daughter, Scheherazade, who hatches a plan to stop this. She asks her father to be the next bride. The vizier says absolutely not, are you crazy? But Scheherazade convinces him, becomes the sultana for one night, and then, a few minutes before dawn, starts telling a story to King Schahriar, confident that he will want to learn how it ends and therefore postpone her death. And so on for as many nights as it takes for the sultan to abandon his crazy plan.

VII.

She always wakes up shortly before dawn, and always tells part of a story until daybreak. Each “night”, in terms of storytelling, is therefore pretty short: two or three pages of a standard book. Maybe 5 or 10 minutes of actual talking.

The tales are of variable length but take several nights each. Occasionally, Scheherazade finishes a story just as the sun rises, but she always convinces the king that she has even more marvellous tales to tell.

VIII.

Scheherazade’s sister, Dinarzade, is heavily involved. Per Scheherazade’s request, she sleeps in the same room (not sure why Schahriar agrees with this) and is the one who always asks Scheherazade to resume her storytelling. King Schahriar usually doesn’t say much but seems happy to let his wife tell stories. He never orders her death.

IX.

The nights are labeled. So are the stories, of course. This is, I think, great for us modern readers! It’s sometimes difficult to read old books, either because old authors weren’t that great at dividing things in paragraphs and chapters of reasonable length, or because we modern readers have zero attention span. But the division into both nights and stories makes it easy to read 1,001 Nights as digestible chunks. At least, at first; later there are changes in how the book is structured.

X.

For the first 68 nights, there’s always a paragraph along the lines of: “Dinarzade woke up and said, ‘Dearest sister, I can’t wait to hear the rest of the tale of the palace in which everyone was turned into stone! Surely the Sultan would be pleased to hear what happened?’”

After 68 nights, however, Galland — who at this point was publishing the third volume of the Nights — inserts a “warning.” He says that his French readership was getting annoyed by the repetitiveness, so he shortened all of the transitions between the nights, asking the scholars to forgive him for not fully respecting the original Arabic text of his manuscript.

XI.

At the end of the 236th night, we get another “warning.” Galland is giving up entirely on the division by nights! From now on, the tales won’t be interrupted at all, and we’ll hear of Scheherazade only between them.

Galland claims that he made this choice because his readers are tired of the interruptions, and also because some of the tales come from sources that don’t mention Scheherazade, Schahriar, and Dinarzade at all. The truth is, his original manuscript wasn’t complete: it breaks off right in the middle of the tale of Prince Camaralzaman. This is our first indication that Galland’s book is in fact a patchwork of several different sources.

XII.

There’s one last warning before “The Story of the Sleeper Awakened,” in which Galland complains about his publisher. Unbeknownst to him, she2 inserted two Turkish stories that were not from the 1,001 Nights and were translated by some other scholar. Galland got angry and switched publishers, and he asked that the two stories be removed from all future editions. Accordingly, they weren’t in the version that I read.

XIII.

So we get 236 nights before the labeling ends, but the book keeps going for a while after that. In Galland’s original division, the warning occurs at the beginning of Volume 7 out of 12. That’s roughly 50% of the full book, from which we can extrapolate the total number of nights to be somewhere between 450 and 500. Not even close to the 1,001 from the title.

XIV.

So what happened?

One common answer is that 1,001 is just a poetic way of saying “many,” and there was never any specific intention of including exactly 1,001 nights. (Some later versions did decide to do that, including Burton’s, but that has nothing to do with Galland.)

I’m not totally convinced; clearly the fact that Galland went out of his way to number of nights suggests that those numbers were important, at least at first. By the last few volumes, Galland has given up on being faithful to the source material. He has inserted quite a few tales that don’t belong to the Nights at all, despite his previous complaint that his publisher did exactly that. He could totally keep going until he reached a length that plausibly spanned 1,001 nights.

Possibly he didn’t care at that point. Or, equally possibly, he just couldn’t get there before he died. Antoine Galland passed away on February 17th, 1715, in Paris. Volumes 11 and 12 of his Nights would be published posthumously, in 1717.

XV.

Also, the frame story never ends. The last part of Volume 12, the “The Sisters Envious of Their Cadette,” concludes without ever going back to Scheherazade. We don’t get to know if her plan worked. Did Schahriar finally decide to let her live? Did Dinarzade ever sleep somewhere else and leave the royal couple alone for once??

This seems like a good piece of evidence that Galland left his work unfinished.

XVI.

In 1806, a new French edition of the Nights added 24 tales to Galland’s translation. These 24 additions came from other sources and were translated by Caussin de Perceval, who did append a short conclusion to the main story. It says that one thousand and one nights did elapse, that Schahriar tells Scheherazade he isn’t angry at the female sex anymore, and that upon hearing this, the people of the empire praise and bless the sultan and his queen.

XVII.

By the way, just like Galland never wrote 1,001 nights, neither am I going to write 1,001 notes.

Consider the title of this post to be a poetic way to say “many.”

XVIII.

When are the 1,001 Nights set? As you might except, the answer is “unclear,” but it’s worse than that. The book opens with this sentence:

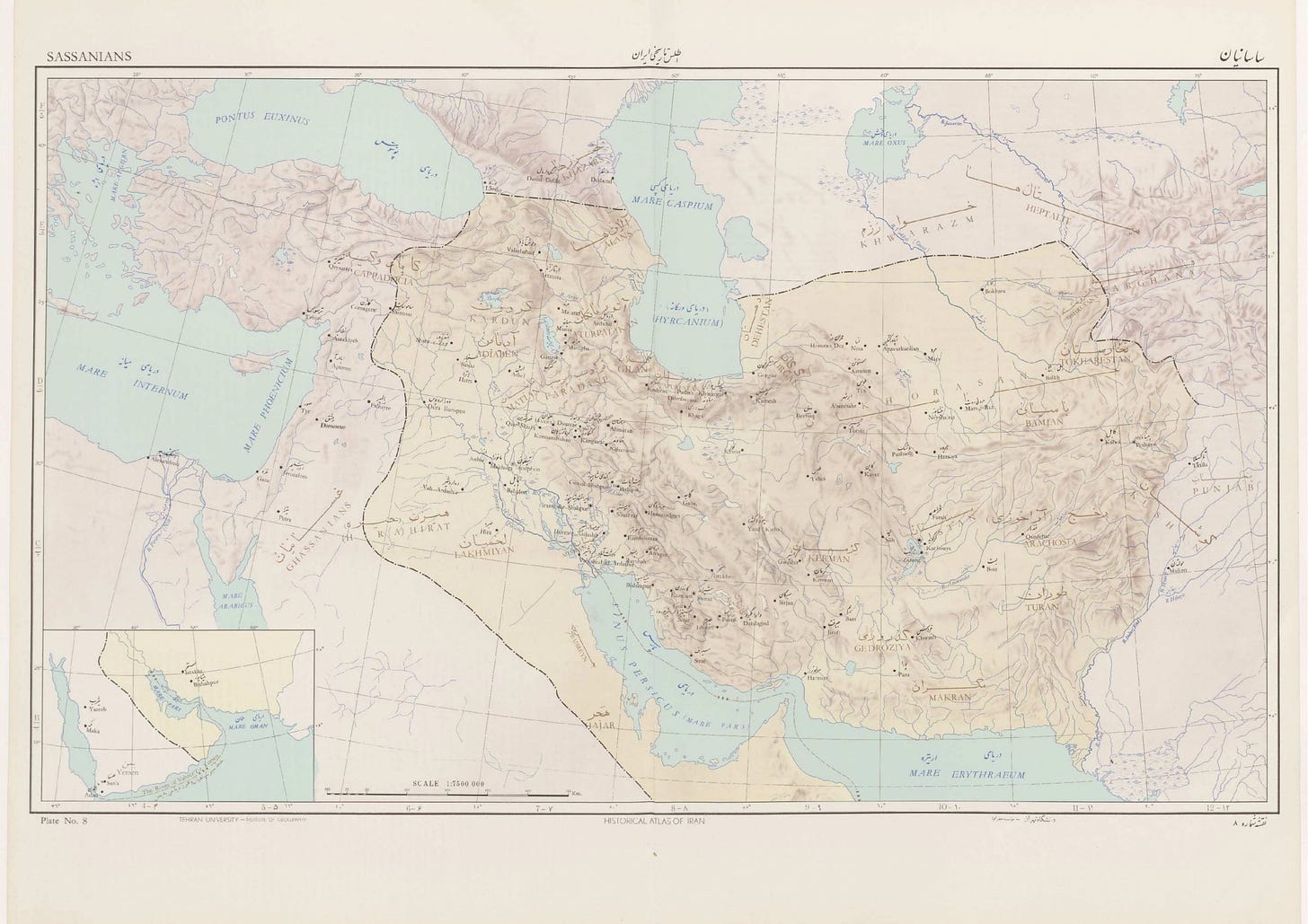

The chronicles of the Sasanians, ancient kings of Persia, who had extended their empire into India, in the large and small islands that are attached to it, and quite far beyond the Ganges, all the way to China, tell that there was, long ago, a king of that powerful house who was the most excellent prince of his time.

That king is the father of Schahriar and Schahzenan, which means that the entire tale of Scheherazade happened, at the latest, during the Sasanian period of Iranian history, and possibly “long ago” even for the Sasanians. The stories she tells are also necessarily set earlier than that.

The problem, of course, is that the Sasanian period of Iranian history lasted from 224 to 651 AD, i.e. what corresponds in Europe to late antiquity and the early Middle Ages. This is inconsistent with:

Almost everyone in the stories being a Muslim. Islam was founded around 610. It coexisted with Sasanian Persia only for a few decades, and those decades were violent, ending into the utter destruction of the House of Sasan and the incorporation of Persia into the Islamic caliphate.

Various Arab-themed concepts, like kings being called sultans and caliphs, the city of Baghdad (established 30 July 762 AD), etc.

Many stories being set during the reign of caliph Harun Al-Rashid, even often involving him as a character. He reigned from 786 to 809 in Baghdad.

In another story, a character measuring time and explicitly saying that the year is 653 according to the Islamic calendar, which, as a helpful footnote informs us, is 1255 AD.

It’s pretty obvious that the setting is intended to be in some idealized ancient era and you’re not supposed to analyze it historically. But it’s amusing that instead of just using a vague trope like “once upon a time,” the original authors of the manuscript went out of their way to give temporal indications that… just don’t make any sense at all.

XIX.

Or maybe there’s more to it. The ultimate origins of the Arabic 1,001 Nights are unknown, but there exists a reference to a lost Persian-language book called the Hezār Afsān, “The Thousand Stories,” which may ultimately trace back to a storytelling tradition among the Sasanian elites. Similarities have also been found between the Nights and ancient folk tales and fables in Sanskrit from India.

So even if many stories within the Nights are evidently a later invention, the origin of the collection may, in fact, be some mix of pre-Islamic Persia and India, and the opening sentence could be interpreted as a nod to that.

XX.

Where is the book set? Occasionally in fictional countries such as the Kingdom of the Black Isles, the Island of the Children of Khaledan, wherever Sindbad the Sailor travels to, and a bunch of fantastical undersea realms in the very very bad “Story of Beder” — but most of the stories take place in real locations.

Baghdad, which for a long time was the round capital city of the caliphate, is by far the most common city to serve as a setting. Other cities in what is now Iraq also make frequent appearances: Mosul, Bassora (spelled Balsora). Elsewhere in the Arab countries, there is Damascus, and… as far as I remember, that’s about it? There’s one short story about a merchant who travels all over, leaving Baghdad for Mecca, and then Cairo, and then Jerusalem, Damascus, Aleppo, Mosul, and various cities in Persia before coming back to Baghdad. Unless I’m mistaken, these are the only references to anywhere in the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant (outside Syria), or Egypt. There’s also the villain in Aladdin’s story, who comes from “Africa,” which is probably the Maghreb.

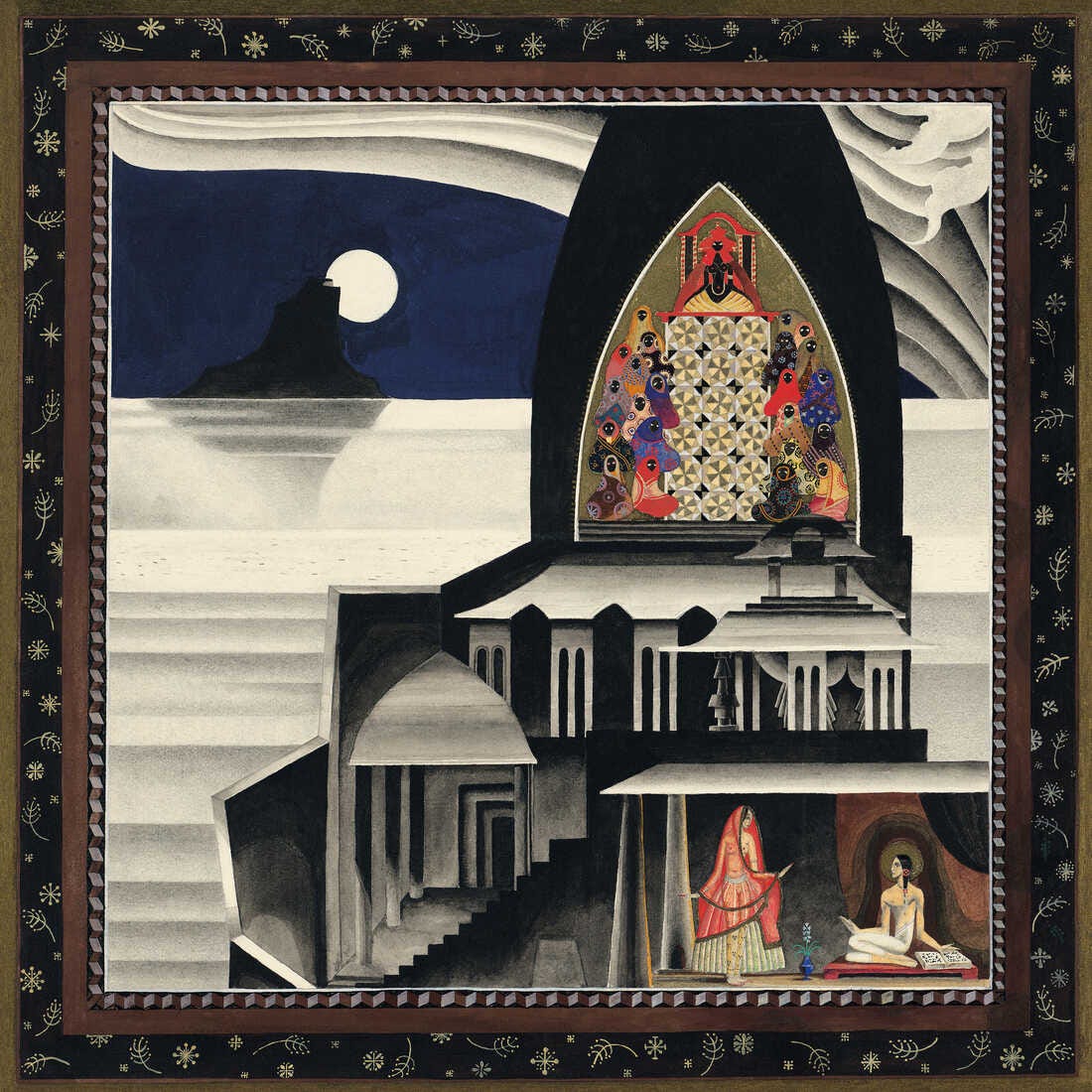

Other than that, we have to look east. Many of the stories are centered on Persian or Indian royalty, but the stories are rarely precise on where exactly their capitals are located. There are several “sultans of India” — probable references to the Delhi Sultanate, although Delhi is never mentioned by name. There are, however, specific references to Kashmir and Bengal, Vijayanagara in southern India, Shiraz in Persia, Samarkand and Kashgar in Central Asia, and China.

XXI.

China is itself an interesting case. It is, famously, the setting for the story of Aladdin, as well as approximately half of the highly symmetrical Story of Camaralzaman and Badoure, the latter of which is “Princess of China.” Nothing about either Aladdin’s or Badoure’s China is Chinese. In both cases it seems to be a generic Middle Eastern country, i.e. ruled by a sultan and full of Muslims. This made for a confusing read: I wasn’t sure what aesthetic I was supposed to picture in my mind when I read about King Gaïour, the father of Badoure, inviting physicians to cure his daughter from a disease she didn’t have (she was just in love with Prince Camaralzaman).

The most likely explanation in both stories is that “China” is about as meaningful as the number 1,001: it’s just a poetic way to say “far away.”

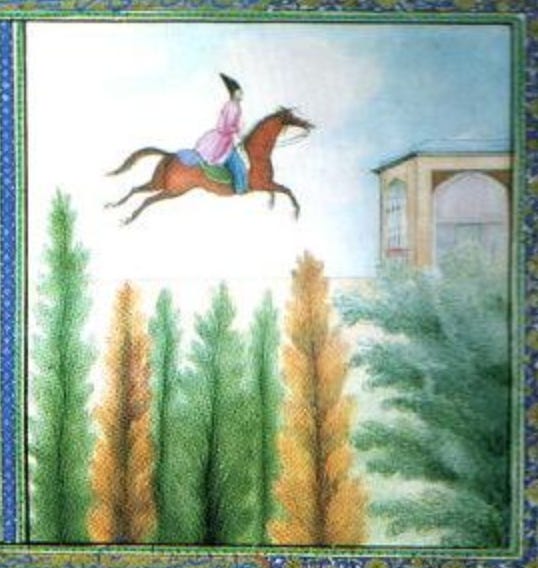

It does mean that when you look up vintage illustrations of Aladdin, you sometimes find things like this:

XXII.

While we’re here, let’s talk about Aladdin. Certainly the most famous tale from the 1,001 Nights, it has the particularity of… not being part of the original 1,001 Nights.

We already saw that Galland eventually ran out of material to translate. But he was nowhere near 1,001 nights, and also his books were super popular, so he wanted to keep going. What to do?

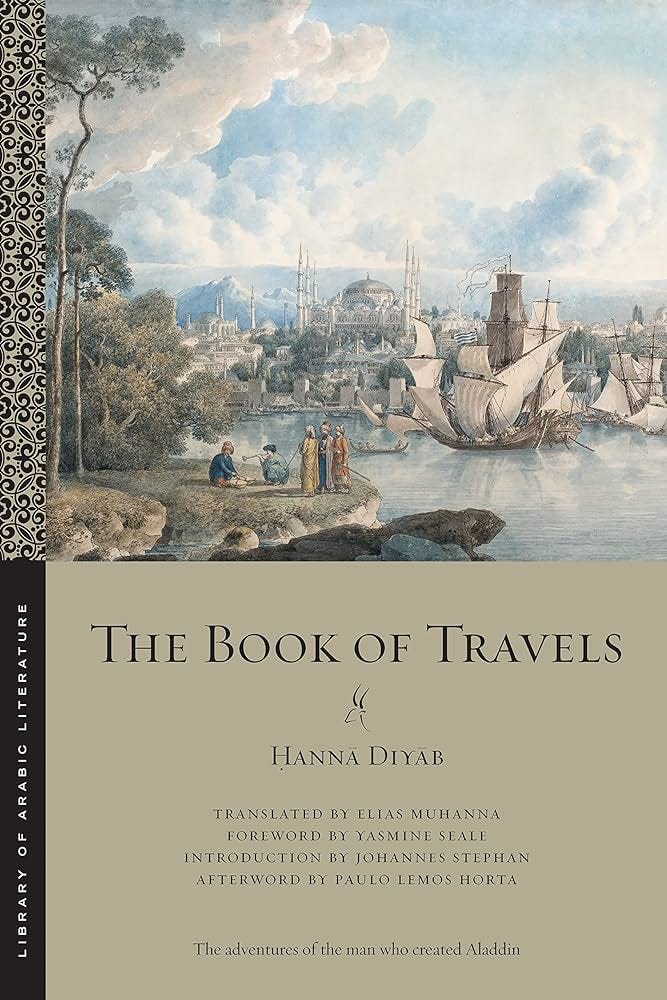

Fortunately, he met, in 1709, a young man named Hanna Diyab, who came from Ottoman Syria. Diyab was a Maronite Christian who, as a teenager, worked with French merchants in Aleppo, learning several European languages. Eventually, an agent of Louis XIV named Paul Lucas, who was hunting for antiquities in the Middle East, invited him to visit Paris. Diyab was received at Versailles by the king and then spent two years in the French capital before going back to Aleppo in 1710 and becoming, like all the characters in 1,001 Nights, a merchant.

Diyab told several stories to Galland, probably directly in French. It’s not clear to what extent they were circulating as folktales in Syria, as opposed to invented by Diyab, but Diyab certainly told versions that were highly personal to him. In fact the character of Aladdin shares several traits with him, like being fatherless and under the authority of a dishonest tutor.

Whatever their origin, Galland liked the stories enough that last 3.5 volumes of his Nights (about 30% of the total) contain nothing but ten tales by Hanna Diyab, including classics like “Aladdin,” “The Ebony Horse,” and “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.”

XXIII.

We’ll go back to Aladdin in a second, but I want to point out that the full title of that last tale is actually “Story of Ali Baba and Forty Thieves Who Were Exterminated by a Slave-Girl,” which communicates rather different vibes than I expected.

XXIV.

As research for this post, I re-watched Disney’s Aladdin (1992), and I’m pleased to report that the plot is reasonably faithful to the original! Evil wizard tricks local bum Aladdin to retrieve a magical lamp with a genie in it; Aladdin manages to keep it instead, becomes rich thanks to the genie, falls in love with the local princess; conflict with the wizard erupts; Aladdin prevails, and he and the princess are happily married.

So far as I can see, the main differences are:

Disney renamed Princess Badroulboudour to Jasmine (yeah I can understand why they did that)

They removed the character of Aladdin’s mother, who plays an important role originally (on behalf of her son, she asks the sultan for his daughter’s hand, despite knowing it’s a ridiculous request)

The genie has an actual personality. In the Galland/Diyab story, when the lamp is rubbed, the genie appears and always says “What do you want? Here I am, ready to obey you like your slave” and then disappears instantly once the wish is asked for.

The “three wishes” motif. In the original story, the genie grants unlimited wishes. It looks like the motif comes from another story in the Nights, but only sorta. See the footnote for more!3

There’s a second genie in the story, bound not to a lamp but to a ring.

The villain in Disney merges two characters, the “African wizard” and the sultan’s vizier. The wizard is canonically very evil, but the vizier seems normal and antagonizes Aladdin only because he wants to marry his son to Princess Badroulboudour.

XXV.

It struck me upon watching the Disney movie that Aladdin is kinda dumb. Well, I’m pleased to report that this is canonically true in the original story too! After he gets the magic lamp, he uses the genie just to… order food, and then sell the silverware. That’s how he and his mother support themselves for literal years. Only later does he realize he can ask the genie for riches, a fancy palace, etc.

It is also canonical that he falls madly in love with the princess after a single glance at her face, but then that’s basically how all male characters work in the Nights.

XXVI.

Galland/Diyab’s “Aladdin” is fun, but it’s also full of plot holes.

I already mentioned the second genie in the ring — it is given by the evil wizard to help Aladdin retrieve the more powerful genie in the lamp. It saves Aladdin when the wizard tries to kill him, and then Aladdin seems to totally forget about it until the lamp is stolen by the wizard, who uses it to teleport himself and Aladdin’s palace (and Princess Badroulboudour with it) back to Africa. Aladdin realizes he still has the ring, and asks its genie to get the palace back. The ring genie, in a rare admission of weakness, says he can’t, since the teleportation was the work of the lamp genie. However, he can teleport Aladdin to Africa so that Aladdin can figure out a way to win back both palace and princess. Then the ring and its genie never come up again.

Another major plot hole is so egregious that the narrator (i.e., Scheherazade) feels obligated to point it out! The wizard steals the lamp while Aladdin is off on a hunting trip. Stupidly, Aladdin, who had recently become a wealthy prince, left the magic lamp lying around in his new palace, allowing the wizard to take it by pretending to be a merchant who replaces old lamps with new ones. The narrator says, “yeah, Aladdin should probably have hidden the lamp, it’s true. But, you know, people have always made mistakes, we still make mistakes, and we’ll always keep making mistakes.”

I want to shake Scheherazade and tell her, You’re the one telling the story! Why are you calling out a flaw in your own tale? Schahriar might be disappointed. He might choose to finally kill you!

XXVII.

Eventually the evil wizard is killed and everything is… fine forever, right? Not so! It turns out the wizard had a younger brother who was also an evil wizard! And so we get 10 totally unnecessary pages in which Aladdin must thwart this other guy. Actually, he doesn’t: he totally walks into the trap set by evil wizard #2 of asking the genie for something that cannot be granted (a roc’s egg). The genie is angry at this extravagant demand and wants to kill Aladdin, but he knows the real culprit is evil wizard #2, so he tells Aladdin that, and Aladdin kills the bad guy. The trap could never work; genies are too powerful. This is bad storytelling!

Honestly the lesson here seems to be that Scheherazade was running out of steam by this point.

XXVIII.

Disney’s Aladdin features a magic carpet. Aladdin and Jasmine use it to travel the Earth during the famous “A Whole New World” song. They visit Egypt, Greece, and China, among other places. All in a single night. Which is impossible: no flying contraption could transport them on such large distances this quickly!

Fortunately, there is an explanation. The magic carpet, in 1,001 Nights, occurs not in “Aladdin” but in “The Story of Prince Ahmed,” and it’s actually a teleportation device. You sit on it, think of a place, and voilà, you’re there. I’m perfectly willing to accept this to be the actual magic in Aladdin’s carpet friend, poetically shown as flying because that’s more cinematic.

XXIX.

By the way, “people being dumb” doesn’t apply only to Aladdin; it’s clearly a common theme to the entire Nights. Time and time again we see things like:

Noureddin, a young man who lost his father, absolutely squandering his inheritance; and, despite people around him telling him “don’t squander your wealth that’s dumb,” being extremely surprised when suddenly he has nothing left.

Prince Camaralzaman spending 10 days trying to recover Princess Badoure’s talisman, which a bird stole, to the point of becoming lost and ending up separated from his wife for years. Like couldn’t you have turned around after a few hours day and just apologized for not having found it?

The fathers of both Camaralzaman and Badoure publicly stating that any doctor who tries to heal their son/daughter and fails will be killed, thus establishing the worst possible incentives.

A sultan being told that someone acted wrongly, deciding on the spot to sentence the presumed wrongdoer to death, sometimes even beheading them himself with his sword; and then being sad when he discovers a short while later that the accusation was a lie.

Scott Alexander speculates that Scheherazade is feeding “training data” to King Schahriar: stories that teach him how to be a good sultan. That seems right, and moreover it seems clear that one of the main lessons is “DO NOT ENACT EXTREMELY DUMB POLICIES LIKE KILLING WOMEN EVERY DAY FOR NO REASON”

XXX.

Related to that point about false accusations, it’s wild how people on 1,001 Nights almost always trust whatever they’re being told, even though, empirically, people lie a lot!

Similarly, there’s magic everywhere; genies and fairies (female genies), magicians of either sex, and magical artifacts are all common occurrences. People seem to be aware of this, because they’re only mildly surprised when they learn some marvellous event was the doing of a genie or witch. Yet they never expect anything magical to happen.

XXXI.

This is less stupidity and more of a tragically funny mistake, but you know how in Ali Baba there’s the secret phrase “open sesame” to enter the cache where the forty thieves have hidden their treasure? Well, you also need it to exit the cache. At some point, Ali Baba’s brother Cassim, who is a bad and greedy man, learns the phrase and goes into the cache. But when he wants to leave with as much treasure as he can carry, he realizes he has forgotten what kind of grain it mentions. He shouts “open barley! open barley!”; but the door doesn’t budge, and he is killed when the thieves come back and find him.

XXXII.

The worst story in the Nights is the story of Beder. Absolutely nothing in it makes sense. It begins with a long introduction of ~30 pages about the King of Persia, featuring several paragraphs that emphasize just how much of a bigger deal the King of Persia is compared to all the other kings, being the King of Kings and all. Eventually Beder is born to the king and his wife, a princess from an undersea kingdom, and his father gives him the throne when he’s fifteen. Then we get some confusing shenanigans involving the politics of a bunch of undersea kingdoms that are an honorable attempt at cool fantasy worldbuilding that unfortunately never quite works.

Later Beder ends up wandering around various cities on land, but outside of Persia, mostly cluelessly. Remember that this is the King of Kings, explicitly the most powerful man alive. He’s turned into an animal multiple times. At some point he walks into a city where all men have been turned into animals, clearly a very dangerous situation, and he just… stays there? He eventually escapes after outsmarting the evil witch queen, but also… he could have escaped at any point? Sent for his army maybe? I don’t understand anything about this.

It’s also one of many tales where almost every single character seems to be a prince or princess. What exactly is the class structure of this society supposed to look like?

XXXIII.

The “Story of the Enchanted Horse,” better known as “The Ebony Horse” in English, is not as stupid as Scott Alexander found it. The horse, which can fly into the sky and travel anywhere super fast, wasn’t used for an assassination attempt; rather, a prince of Persia is just too rash and flies before the owner of the horse has time to give him instructions. So he’s stuck in the sky for a while, until he figures out the mechanism and lands in a random location. That random location is, of course, the palace of a Bengali princess.

(What percentage of the Earth’s land area consists of palaces? In the Nights, probably something like 25%)

The Story of the Enchanted Horse is also unique in that it ends with an straightforward moral, given in italics and everything:

Sultan of Kashmir, when you want to marry princesses who ask for your protection, learn to first ask for their consent.

Surprisingly modern!

XXXIV.

I went into the Nights expecting a lot of recursion — stories within stories within stories. There’s some of that, especially in the first few volumes. But either Scheherazade or Antoine Galland eventually got tired of the gimmick. The second half of the book is only regular stories, with the occasional mention of Scheherazade between them. It doesn’t feel that special.

So although Scott Alexander’s theory, that 1,001 Nights is a book about how you might be in a book yourself, is fun, that’s not really my main takeaway.

XXXV.

Instead I think of One Thousand and One Nights as being about perseverance.

Sometimes we decide to embark on big iterative projects. Write dozens of weekly blog posts. Translate a long manuscript from Arabic. Exercise your abs every morning. Read an entire 12-volume book from the 18th century so you can write a long blog post about it. Tell sufficiently many stories that your king will decide to spare your life and stop killing off all of the kingdom’s young women.

In all cases the project is daunting at first. You don’t know if you’re going to manage to do it 10 or 100 times, let alone 1,001. But you try anyway. You start, and then you just keep going.

And you fail, in all sorts of ways. Maybe you’re Antoine Galland and you’re forever waiting for new manuscripts, finally deciding to transcribe random tales told to you by a Syrian friend so you can extend your book. Maybe you run into annoying publishers who distort your work. And maybe you die before you manage to finish.

Or maybe you’re Scheherazade and at some point you really can’t think of good stories anymore, so you come up with the nonsensical Story of Beder, or the pretty pointless 10-page epilogue to Aladdin. Or you’re me, and you realize that writing a long blog post about 1,001 Nights was both more ambitious and less of a good idea than you initially thought. It’s fine! The process needn’t be perfect. It just needs to keep going.

Because when you do do 1,001 of something, or at least get a good part of the way there, good things happen. You save the Persian Empire from a feminicidal maniac. You write a collection of stories that will become forever enshrined as a masterpiece of world literature and be adapted into a popular movie by an American multinational 280 years later. And maybe, if you’re even luckier than that, you find a magical artifact with a genie inside it, and you end up marrying the beautiful daughter or son of a sultan, and live contentedly for the rest of your nights.

The quotations from the main text are my translation from the French.

I believe it’s a “she” though it’s kind of unclear. The first 7 volumes were published by “the widow of Claude Barbin,” née Marie Cochard. Claude Barbin was a Parisian bookseller whose business was taken over by his widow when he died in 1698, but then she died in 1707. The Claude Barbin shop kept going anyway, apparently under the direction of another widow, “la veuve Ricoeur,” who seems to have published Volume 8 with the unwanted Turkish tales.

The idea of a genie granting three wishes appears in “The Story of the Fisherman” (otherwise known as “The Fisherman and the Jinni”), but only obliquely. The genie has been trapped into a jar by King Solomon for centuries. During his captivity, he tells himself, “if someone frees me in the next hundred years, I’ll make him wealthy,” but then a hundred years pass, so he changes the vow to various successive things until it’s “make my liberator a powerful monarch and grant him three requests per day, no matter what they are.” But nobody opens the jar at that point either, so the genie becomes angry and vows to kill whoever frees him instead.

Thus the three wishes idea appears in the 1,001 Nights, but 1) only as a hypothetical reward, and 2) it’s three wishes PER DAY! It looks like it became three wishes total only in the Burton translation, and the motif was merged with the Aladdin story only by Disney.

Fantastic review! It's a perfect companion to the review on ACX. Notes 18-21 were especially edifying to me and totally overlooked by Scott.

Thank you, this was wonderful to read and I love how you tied it all together in the end.