1980s Jane Jacobs on Cities, States, and City-States

A review of ‘Cities and the Wealth of Nations’ and ‘The Question of Separatism’ 🏙️

The essay below won 3rd place in Astral Codex Ten’s 2023 Book Review Contest. It was originally published on ACX, but I’m reprinting it here as my ‘canonical’ version with minor edits.

I wrote the review in March 2023, and since then, in part thanks to the abundant and high-quality discussion in the ACX comments, I’ve updated my views somewhat. I think Jane Jacobs probably made several mistakes of economic theory that weaken some of her core points, and I agree with the common critique that her arguments are too lacking in quantitative data. However, I stand by the review and still think her books point compellingly in the right philosophical direction.

All footnotes are new commentary from September 2023.

If you know Jane Jacobs at all, you know her for her work on cities. Her most famous book, published in 1961, is called The Death and Life of Great American Cities. It criticizes large-scale, top-down “urban renewal” policies, which destroy organic communities. Today almost everyone agrees with her on that, and she is considered one of the most influential thinkers on urban theory.

This is not a review of The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Perhaps it would be, if I had become interested in Jane Jacobs’s ideas on cities like a normal person. But I didn’t: I started with two books that came to me by random chance, or fate, if you want to call it that.

The first book is Cities and the Wealth of Nations: Principles of Economic Life, first published in 1984. I found it, as it happens, in a city, more specifically in one of those public bookshelves where people give books away. A lucky find: my copy is somehow signed by Jane Jacobs herself. A friend said that although this book is read less often than The Death and Life etc., it actually contains the real gems from Jane Jacobs’s thought. So I was quite excited to read it, by which I mean that I kept the book on my bookshelf for more than a year before finally digging into it.

Mere days after I finished reading it, thinking it was indeed one of the best essays I’d ever read, I checked the same public bookshelf again. And lo! There was a second Jane Jacobs book: The Question of Separatism: Quebec and the Struggle Over Sovereignty.

This book is Jacobs’s least read. It was published in 1980, right after the first referendum where Quebecers voted to remain a part of Canada. It is based on lectures that Jacobs (who was an American but had moved to Canada in 1968) gave in Toronto right before the referendum. It’s not hard to guess why the book didn’t have a huge (read: any) impact. First, most people outside Quebec or Canada don’t have any reason to care. Second, the essay — which was written in English — argues in favor of the secession of Quebec, which virtually no one among the English-speaking population of Canada agreed with. The natural reaction from Canada’s intelligentsia was to ignore the book altogether. Meanwhile, few people in Quebec itself read it, since the referendum was over; it wasn’t even translated into French until decades later.

As a result, The Question of Separatism sits awkwardly in Jane Jacobs’s bibliography, as if it were “a mistake in an otherwise brilliant career,” like I read somewhere. In a 2005 interview, one year before her death, Jacobs said that no journalist ever asked her about it.

But the book was not a mistake. I don’t claim any special insight here: Jane Jacobs herself said so in that same interview. She said that she would have written the same book in 2005, “because that’s the way it is in the world, and it still holds.” Besides, The Question of Separatism is in fact not that much about the specifics of Quebec’s political situation, but rather about interesting generalities: what size means for countries and organizations, and why the fate of nations depends primarily on what happens in their cities.

Taken together with Cities and the Wealth of Nations, which Jacobs wrote a few years later to expand on those ideas, we get a coherent and deeply interesting philosophy of economics: one that favors the local scale, cities and small countries, antifragility long before Nassim Taleb coined the term, and avoiding grandstanding theories that always fail to take into account the real complexity of the world.

I. A Fake Mystery

Cities and the Wealth of Nations opens on an economic mystery.

“For a little while in the middle of this century,” writes Jacobs, “it seemed that the wild, intractable, dismal science of economics had yielded up something we all want: instructions for getting or keeping prosperity.” This was the 1940s to 1960s, and economists thought they had it all figured out. It was the golden age of high modernism and scientific technocracy. Everywhere from China to the Soviet Union to the United States and Britain and the nascent European Economic Community, leaders were coming up with elaborate plans, rooted in macroeconomic theories, that were supposed to guarantee future wealth and avoid economic crises.

The theories had been developed by many thinkers over the previous two hundred years: Richard Cantillon, Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, Karl Marx, John Maynard Keynes. Jacobs explains how they each had their own ideas of how the economy worked, disagreeing over things like whether supply or demand was the main driving mechanism, but they all agreed on a fundamental fact: inflation and unemployment have an inverse relationship to each other, like a seesaw. High inflation comes with low unemployment; high unemployment comes with low inflation, or even deflation when prices drop.

The Great Depression, a time of deflation, had provided proof of the seesaw. Big government projects, as prescribed by Keynesians, were a way for states to reduce unemployment and bring the seesaw back in a balanced state. Economists developed fancy models, based on historical data, to predict the behavior of the economy. The Phillips curve in particular became popular.

It was the golden age of technocracy; it was the triumph of high modernism. From now on wealth was assured, because we weren’t blind anymore: we had the curves.

And yet — by the 1970s and 1980s, when Jane Jacobs was writing, the theories all stopped working. There was high inflation and high unemployment. People called it stagflation. Keynesian advisers in various governments were devastated: either their ideas were wrong, or they were applying them wrong. Economists such as Milton Friedman, from a rival school of economists called the monetarists or the Chicago school, came to the rescue — but their remedy, Jacobs believes, only made things worse. Whatever governments did to increase employment made inflation worse; whatever they did to attenuate inflation killed employment. The seesaw from the theories was working in application, even though it didn’t explain reality anymore. Stagflation was not supposed to exist, so stagflation could not be fought.

At this point we’re near the end of Chapter 1, the densest part of the book. Jacobs has artfully guided us along economic history and laid out the mystery for us. What’s going on? we wonder. How are we supposed to deal with the two-headed monster of stagflation, if all economists are stumped?

Then Jacobs, in a masterstroke, flips the whole thing over. I was impressed enough that I would have inserted a spoiler alert here, if it didn’t feel so silly putting a spoiler alert in an essay on economics.

Stagflation is not a strange monster from legend. It is, Jacobs says, just the normal state of everything. Backward economies are in fact constantly in a state of stagflation. The prices in a poor country like Portugal or India (her two examples) feel low for an American or Canadian, but they’re high for most Portuguese or Indian people. At the same time, Portugal and India provide too few jobs to their residents. Inflation and unemployment are both perennially high, and none of that feels surprising whatsoever.

Stagflation, in short, is just good ol’ poverty. All these fancy economists, from Cantillon in 1700s France to Keynes and Friedman in the 20th century Anglosphere, were thinking and writing about unusual places: rich countries that were undergoing fast economic development. They were making the classic mistake of treating poverty as a mystery and wealth as a given, when in fact poverty is the normal order of things and wealth, when it does occur, is what warrants an explanation. The result is that we don’t really know how to fix the economy of poor countries, nor do we know how to deal with decline in rich countries, whether we call it stagflation or something else.

Jacobs derives from this a pretty damning view of macroeconomics. It is to her a science that has failed again and again, each time engulfing the equivalent of billions of dollars in wasted wealth. “We must,” she writes at the close of Chapter 1, “find more realistic and fruitful lines of observation and thought than we have tried to use so far. It is bootless to choose among existing schools of thought. We are on our own.”

Fortunately, she has some ideas.

II. Nations and the Wealth of Cities

The original sin of macroeconomics, Jacobs believe, is to treat sovereign countries, or nations, as the main unit of economic analysis.

This error, she claims, goes back to mercantilism, one of the first formal economic policies. Oversimplified, mercantilism states that wealth is synonymous with the amount of gold and silver in a nation’s treasury. This makes nations the main unit of economic analysis by definition. It’s a tautology — and one that was somehow embedded so deep in economic thinking that even the non-mercantilist Adam Smith would eventually choose, for his masterpiece of economic theory, the title An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Today, even though mercantilism has long been obsolete, we perpetuate the same tautology whenever we talk of the Gross Domestic Product or look at the very nice charts from Our World in Data, which for the most part allow only one level of resolution: sovereign countries.

Of course, nations are an economically important concept because of that one property: they are sovereign, and therefore they write laws and implement policies that affect the economy. These policies can be productively compared. But that’s about it — for everything else, nations aren’t the right way to think about wealth.

One reason is simply that they’re very different from one another: “it affronts common sense,” Jabobs writes, “to think of units as disparate as, say, Singapore and the United States, or Ecuador and the Soviet Union, or the Netherlands and Canada, as economic common denominators.” I would add that countries are arbitrary and changing: when the Soviet Union was replaced by 15 sovereign countries, the economic reality didn’t suddenly reshape itself to match the new borders. Lastly, nations contain, under the hood, many sub-economies that are also highly different from one another.

None of that is secret or forbidden knowledge. Everyone has always been aware that New York City, or Milan, are economically very different from rural Mississippi or Sicily. But I find that it’s far easier to think in terms of “the United States” or “Italy,” especially when you’re not from there. Nations are an abstraction of real-life complexity, and are accordingly very tempting to use.

Also, they’re often the entities that collect statistics, which is another difficult-to-resist temptation for anyone who likes quantitative data.

Cities as Radiators of Economic Forces

If nations aren’t the best unit to analyze the economy, what is? This is a Jane Jacobs book, so the answer is obviously going to be cities.

Jacobs doesn’t actually give a clear argument why. Maybe that was in her previous book, The Economy of Cities. So far as I can see, her reasoning is, ironically, a bit tautological: “all developing economic life depends on city economies; it depends on them by definition because, wherever economic life is developing, the very process itself creates cities and has probably always done so.”

But so far as I can see, this reasoning is correct. Cities concentrate people, and therefore economic life, and therefore economic power. The driving force for all this is a phenomenon that, from what I gather, was discovered by Jacobs when she wrote The Economy of Cities: import replacement.

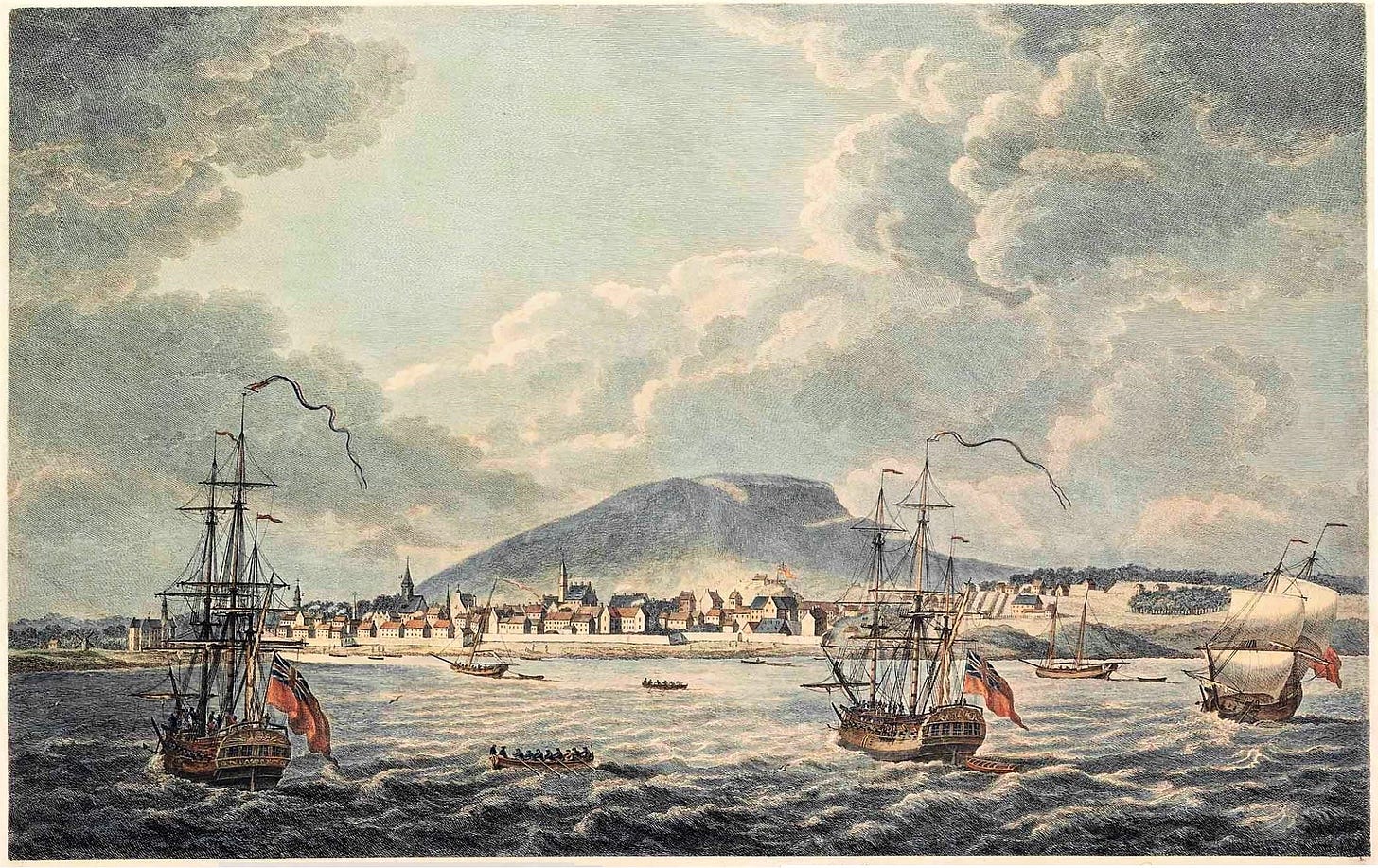

Consider, say, Boston back when it was a tiny settlement, not yet a city, in colonial times. At first, Boston didn’t produce much, especially not much that would be of interest to its main trading partner, London. It exported some natural resources: timber, fish.1 Whatever else the Bostonians needed, they needed to import it from other cities, again mostly London. (Remember to think of imports and exports in terms of cities, not nations.) For instance, at first, all metal tools in Boston came from European cities, and were paid for by the revenue from selling the timber and fish.

Then, one day, some Bostonians decided to build an ironworks and make metal tools themselves.

This wasn’t of any interest to London or other European cities. The Bostonians weren’t nearly as good or efficient at making metal tools as Londonians were. So Boston couldn’t export the metal tools back to Europe — but it could use them internally, and also export them to other American cities that were about as poor as Boston was, or poorer. Internally, this meant the spark of a manufacturing economy in Boston, as easily obtained metal parts made it easier for other Bostonians to replace other imports from European cities, and eventually develop a symbiotic network of industries. It also meant that the revenue from fish and timber could be used to import new things, including new innovations from European cities (which would later become opportunities for more import replacement). And because there were customers for Boston-made metal goods in New York and Philadelphia, and eventually Cincinnati and Chicago and Pittsburgh as these cities came into existence, it meant additional revenue for Boston that it could reinvest into developing its production further.

For Jacobs, virtually all city development can be seen through the lens of import replacement (which, to be clear, has approximately nothing to do with policies of import substitution industrialization; import replacement is not a policy, but a naturally arising free market phenomenon).2 Her book contains many other examples than Boston, such as Venice, which started off in the early Middle Ages as a small town that sold salt to Constantinople, but then diversified its production to become one of the wealthiest cities of its time; or Taipei and Kaohsiung, two cities in Taiwan that kickstarted their development not long before the 1980s, by forcing expropriated landlords to invest into local import-replacing businesses. One is reminded of Scott’s review of How Asia Works.

Import replacement, then, is what makes cities economically powerful. And this power is so great that it causes ripples in distant places. In fact it is the main reason that anything happens at all in non-city areas.

Jacobs gives the example of Bardou, a small village in southern France. Bardou looks like this:

To the extent that Bardou ever had an economic life, that life was almost entirely driven by distant cities. In ancient times, the area was populated because of iron mines nearby. The mines were exploited to serve the needs of people in the distant cities of Lugdunum (Lyon), Nemausus (Nîmes), or even Rome. As Jacobs notes, we could say that the mines served “the Roman Empire,” but that would be another example of using the abstraction of sovereign countries when we should instead be specific. It was Lugdunum, Nemausus and Rome that wanted the iron — not some random rural area of the empire, and certainly not the part of the empire in which Bardou was located.

Eventually the mines and the region were abandoned. More than 1,000 years later, peasants moved into the area and built the modern village. For centuries they lived a wretchedly poor life of subsistence farming. No cities exerted any influence on it, and indeed nothing happened. Then, in the 19th century, the people of Bardou learned that they could improve their situation by moving to distant cities such as Paris, and most of them did. Again, the force wasn’t being exerted by “France”; Bardou was already part of France. The force was specifically being exerted by Paris and other cities with jobs for poor peasants.

By the 1960s, only one old man was left. That’s when two foreign visitors, a German and an American, happened upon the village, decided to buy most of it, revitalized it, and turned it into a tourist spot (and even, for a brief time, into a set for a movie company). Today Bardou is a popular place for travelers — who are mostly city people, and spend money that was mostly earned in cities.

The Bardou story contains examples of several of the forces that import-replacing cities radiate, according to Jacobs. These forces are central to her thinking. There are five of them:

Markets. Cities house a lot of people who need a lot of goods and services, and are therefore strong markets to sell goods and services to. This was the force that acted on the Bardou area when it was a Roman mining region, and again today when it functions as a tourist spot for city vacationers.

Jobs. Prosperous cities tend to attract people from elsewhere who come for work, which is what depopulated Bardou in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Technology. New things are disproportionately invented in cities, and only later do they affect other regions. Bardou received a windfall when the movie company rented it for location shots; that would obviously not have been possible before movie technology was invented.

Transplants. Sometimes cities send transplanted factories to other regions. (I don’t think that happened to Bardou.)

Capital. Cities can provide money directly to other regions, for instance as subsidies, loans, or development grants. I’m guessing that Bardou received some assistance from the French national or regional governments at some point.

These five forces determine pretty much everything that happens in rural regions. We can distinguish at least seven types of these regions, depending on which forces act upon them.

Seven Types of Rural Regions

When the five forces act together in a reasonably balanced manner, this creates a type of rural area that Jacobs calls a city region. This is a confusing name, because it absolutely does not mean “any region around a city,” nor does it mean “suburbs.” We know this because Jacobs spends several pages telling us which cities have a city region and which don’t. For instance, Tokyo has a city region, the largest in the world as of 1984, but Sapporo, in northern Japan, doesn’t. Boston, Paris, Milan, and Taipei do; Atlanta, Marseille, Naples, or Manila don’t.

A city region, in Jacobs’s terms, is the rural hinterland around a city that gets “radically reshaped” by that city’s economy. It contains a mix of productive farms, prosperous satellite towns, and factories that have moved out of the city, forming a symbiotic network of commercial and industrial enterprises. City regions “are the richest, densest, and most intricate of all types of economies except for cities themselves,” she writes. They arise thanks to the interplay between the five forces.

In another of her wonderfully told examples, Jacobs summarizes a book about Shinohata, a real Japanese village (but with a fake name, for anonymity) on the outskirts of the Tokyo area. In the post-war era, Tokyo was expanding rapidly, and so was its city region, eventually reaching Shinohata in the 1950s. Before, most families in the village lived from subsistence farming and exported a little bit of silk to distant places. Almost no one moved out to Tokyo or other cities. But after 1955, the markets, jobs, technology, transplants, and capital from the city all came bearing upon Shinohata at the same time, totally transforming it.

The growing city markets meant that most families could switch to new cash crops and make more money. New jobs were opening up in Tokyo for the sons and daughters of Shinohata, many of whom left — prompting the remaining farmers to buy labor-saving equipment, which made productivity soar. Soon, a large food processing factory was transplanted into the village, providing additional jobs and money and causing a variety of smaller businesses to pop up in the area. After a typhoon disaster in 1959, a recovery grant from the government — an example of city capital — was put to good use by providing much needed excavation work and infrastructure development.

Shinohata is in Tochigi Prefecture, but I couldn’t figure out what its real name is. In any case, it is part of the vast Greater Tokyo Area, a region that combines the largest city in the world with large tracts of rural land, and occupies a disproportionate space in Japan’s demographics and national economy.

Rural regions far from import-replacing cities are generally less lucky. Their plights take different forms, depending on which of the five forces dominates the others.

An oversized market force creates a supply region: a place that exploits agricultural or natural resources and exports them to distant cities. These regions (the most common in the world) can be rich or poor, but they’re never economically dynamic — and they’re very sensitive to disturbances in the markets that they serve. Jacobs’s example is Uruguay, a country that grew rich selling animal products to European cities in the early 20th century, but then suffered immensely when the market changed in the 1950s, propelling the nation into a succession of economic crises.

An oversized jobs force creates a region workers abandon. When workers leave to work in distant cities, they improve their own situation, but their region of origin stagnates. This is true even if the workers send remittances, as in her main example, the town of Napizaro in rural Mexico. Most men from Napizaro work hundreds of kilometers north, in the factories of the dynamic city of Los Angeles. Even though they send back a lot of money to their families in Napizaro, Napizaro is never able to develop, because it imports everything it consumes and doesn’t replace those imports.

An oversized technology force creates a clearance region. The example here is the Scottish Highlands, where a technological innovation was introduced in the late 18th century: a new breed of sheep. (Technically this was a rural invention, but the introduction to Scotland was devised by businessmen in London.) The new sheep greatly improved the yields from the land, but at the cost of violently displacing a large number of poor tenant farmers to make room for pastures. So it goes for other technologies, like farm machinery: when they are introduced to a poor rural region that isn’t integrated into an import-replacing economy, they just replace workers and leave them idle, poorer than before, or forced to emigrate.

An oversized transplant force creates a transplant economy: a place that depends on industries that it did not generate itself. Getting a transplanted factory is always tempting for the governments of poor regions. But while the new jobs do alleviate poverty, transplants almost never lead to durable economic development (with rare exceptions, such as Taiwan). Jacobs has multiple examples, but the one I like most is Iran just before the revolution, when the Shah used oil money to buy a helicopter factory from the United States — thereby spurring a lot of development in the United States, where many companies got involved in building the factory, and almost none in Iran.

Finally, an oversized capital force creates an artificial city region. In the US, the Tennessee Valley Authority was a Depression Era program to develop a poor region using federal government money. The hydroelectric dams and other infrastructure that the money bought seemed to be great successes at first, and to be sure they did reduce poverty. But problems later appeared, and today the region isn’t particularly dynamic, in addition to being riddled with environmental issues. Jacobs explains that the federal aid could never truly help, because the Tennessee Valley has always lacked an import-replacing city. Subsidies, grants, and loans give at best the illusion of development.

None of these five types of rural regions tend to do great in the long run, unless they manage to generate an import-replacing city. But at least they receive something from distant cities. It’s far worse when a region is untouched by city forces at all, as Bardou was for a long time. Or as was a hamlet in North Carolina that Jacobs calls “Henry” for anonymity reasons, but which we can safely reveal to be Higgins, in the Appalachian region. Here is what Higgins looked like in 2013 on Google Street View:

There is a nice modern road in that screenshot, but between its 18th-century founding and the 1920s, there wasn’t even a path that a horse-drawn wagon could use, and so Higgins was extremely isolated. It barely sold anything to anyone outside, and accordingly imported very little. The people lived from subsistence farming. Their lives were so difficult, so focused on sheer survival, that they gradually forgot many of the skills and techniques that their British ancestors had, like candle making, weaving from a loom, and even masonry. When Jacobs’ aunt arrived as a Presbyterian missionary in 1922, and suggested that they build a church out of stone, the people of Higgins confidently stated that this was impossible: mortar just wasn’t strong enough. “These people came of a parent culture that had not only reared stone parish churches from time immemorial, but great cathedrals,” Jacobs writes, and yet eventually they forgot that stone buildings were a possibility at all.

Such is the fate of regions that get cut off from cities. Jacobs calls them bypassed places. Sometimes these places are entire countries, such as Ethiopia, once the seat of an empire, but which as of the 1980s had barely any links to cities except its own backward ones. Unsurprisingly, Ethiopia has high prices (for Ethiopians) and too few jobs. That will always be so, unless one of its cities can start the process of import replacement.

III. Should Everything Be a City-State?

That was roughly the first half of the book. After that, Jane Jacobs discusses various consequences of her theory, including why decline happens and how we can, in theory, prevent it. We’ll get there — but first, it’s time for a detour through the other book, The Question of Separatism, which provides a great case study of Jacobs’s ideas.

After an introductory chapter in which Jacobs acknowledges that separatism always makes everyone emotional, and warns that she’s going to study it in a dispassionate manner anyway, she starts by describing the issues in Quebec and Canada through a specific lens. You can probably guess which lens. That’s right — cities. To her, the question of Quebec separatism is primarily the question of how the two main cities in Canada, Toronto and Montreal, have coexisted and will coexist in the future.

At this point you need at least a basic understanding of Canadian history. Here’s a quick primer, focusing on those two cities.

Canadian History Speedrun (Jane’s Version)

Canada, a word that used to refer to the large valley around the St. Lawrence river and the Great Lakes, was originally a colony of the Kingdom of France. Then the Kingdom of Great Britain conquered it in 1760. For various reasons, most of the French settlers stayed in Canada rather than emigrating to France or being deported, so at first, a small British elite ruled over a mostly French-speaking and Catholic colony. However, immigration from the British Isles, as well as from the newly seceded United States (loyalists who wanted to live in a monarchy rather than a republic for some reason) eventually tipped the linguistic and cultural balance. The population sorted itself such that the lower part of the valley (what is now Quebec) remained French, while the upper part (what is now Ontario) became English.

The exception to this trend was the city of Montreal. Although located in Quebec, it became an English-speaking city and the hub for the British merchant elite. For at least a hundred years, it was the main city in Canada across almost all metrics: population, wealth, manufacturing, political influence.

In the middle of the 20th century, Montreal grew enormously and became French-speaking again, owing to immigration from rural Quebec. It became the center of Quebecois culture and, with its increasingly educated population, the breeding ground for new ideas, including separatism. At the same time, the main city in Ontario, Toronto, was growing even faster. Immigrants from all over Canada and other countries poured into it (including Jane Jacobs herself). Sometime around 1970, it became bigger and wealthier than Montreal, and replaced it as the main economic hub. Many people attribute this to the rise of Quebec separatists, which supposedly scared the Anglo elite of Montreal into moving all the banks and companies to Toronto, and, to be sure, some of that happened — but of course, Jacobs prefers explanations that rely on city economics.

One of the reasons for Toronto's economic and demographic growth is that it became the nexus of what Jacobs calls a conurbation, and would have called a city region if we were in the other book. In case you craved another concrete example of a city region, here’s a map of Ontario with two ways to define Toronto’s so-called “Golden Horseshoe”:

Meanwhile, Montreal never generated a conurbation or significant city region. This is Jacobs’s main hypothesis for why it was overtaken by Toronto, though she doesn’t give a lot of detail on why it happened. In any case, the result was that Montreal lost its status as the economic capital of the country. It became a regional city.

The problem is that regional cities tend to do poorly. The nature of nations is to centralize everything in one place (we’ll come back to this). That’s why Paris has a large and rich city region, but Lyon and Marseille don’t. That’s why London looms so large in the UK’s economy while Glasgow or Manchester now contribute very little.3

There’s nothing wrong per se with being an economically stagnant regional city. Such cities can be fine places. When they’re the center of a supply region, like Calgary and Edmonton in oil-rich Alberta, they can even be wealthy. The complication for Montreal, though, is that its previous status as the main Canadian metropolis made it grow too large for this purpose. Yet, at the same time, Montreal plays an outsized cultural role for French-speaking Canadians — one that Toronto doesn’t even come close to fulfilling.

So, Jacobs sees only decline for Montreal. And she thinks this means decline for Quebecois culture generally. Without a strong import-replacing city, Quebec will become a patchwork of supply regions, regions that workers abandon, or transplant economies, like the poverty-stricken Atlantic provinces in eastern Canada already are. Either the Quebecois resign themselves to this fate, she says, or they fight it — and the only true way to fight it is to declare independence.4

As of the 1980 referendum, she thinks they should go for independence.

Generalized Separatism

Quebecers did not go for independence, neither then in 1980 nor in 1995 when they voted on the question again.

If they had, it would probably have been an example of a peaceful secession. Jacobs points out that there haven’t been many of those, if you exclude the decolonization of overseas imperial possessions (like Canada from Britain). Non-peaceful secessions have been common, but in those cases the destructiveness of war tends to overshadow everything else, economically speaking. In fact that might be the main reason most of us intuitively dislike separatism: we associate it with conflict.

But peaceful non-colonial secessions do happen. Since 1980 there have been several more cases, like Czechia and Slovakia. When Jacobs wrote her book, though, the only good example she could think of was the independence of Norway from Sweden in 1905. She tells a great account of the process, noting that the outcome wasn’t predetermined: Sweden didn’t want to lose its western province, and did what it could to contain Norwegian nationalist sentiment. But Norwegian nationalist sentiment won — and importantly, both Norway and Sweden seemingly benefitted. Neither of them was particularly rich in the 19th century, and Norway was in fact dirt poor, which is why so many Norwegians escaped by emigrating to North America. Yet after the dissolution of their union, the two countries developed quickly, and both are now among the wealthiest countries in the world. They certainly didn’t disintegrate.

(Of course, in Norway the wealth is due in large part to the oil that they discovered in the late 1960s. But they were pretty advanced by that point already — advanced enough that they could use the oil to develop their own industry, rather than get rich quick by exporting it raw, which is what keeps many countries trapped as supply regions.)

When people argue against separatism, they often tout the benefits of being large. A Canada that would be split in two would mean smaller markets, and a weaker political counterweight to the United States. (Not to be mean to Canadian readers, but this argument seems delusional to me — I don’t think Americans currently see Canada as a political counterweight of any significance.) It would certainly be less prestigious. Large size, Jacobs says, is associated with power, and we admire power. We love slogans like “unity makes strength.”

But after the medium-sized country of Sweden-Norway became the two smaller countries of Sweden and Norway, they both did well. Small size is less powerful, but it has its own advantages, such as nimbleness and ability to fail non-catastrophically. Small size also allows more diversity in cultural and economic matters, and here Jacobs waxes philosophical, pointing out that favoring diversity over uniformity is a recent, post-Enlightenment idea that has not yet been fully embraced in politics.

We can see analogs everywhere. Europe, split into numerous small countries from the Middle Ages onward, became far more advanced than China, which has been unified more often than not. The city-states of ancient Greece and Renaissance Italy are seen as golden ages of Western civilization, even if they weren’t part of larger political units and therefore constantly went to war with one another. In business, large companies are impressive and powerful, but people always complain that Google or Microsoft have become stagnant and that the best place to work is tiny startups of about 2 cofounders and 4 employees. In biology, humans are more successful than numerous larger animals, and in terms of raw numbers, small animals like rats or insects are the most successful of all.

Jacobs’s point isn’t that smaller is always better. Her point is that the converse statement, “bigger is always better,” is false — despite how intuitive it feels for political entities. Just like we don’t view a small nation like Switzerland or Singapore as a failure of unity, we (and in particular, Canadians) shouldn’t see the secession of a place like Quebec, if it’s done peacefully and democratically, as a failure either.

Still, some people in online reviews of the book complain that this argument is a bit thin, especially considering that it serves as the foundation for the later chapters (which are more directly about late 1970s Quebec politics). Sure, small is beautiful, but large states are great for stability, peace, markets, whatever. If the potential benefits of small national size are Jacobs’s strongest argument, then we can breathe a sigh of relief and go back to agreeing that separatism is bad.

Pointing out the widespread bias in favor of unified political entities does seem valuable to me, but okay, fair enough. Does Jacobs have deeper reasons why separatism might be a good idea in general? Yes, and for this we go back to the second half of Cities and the Wealth of Nations.

Why Nations and Empires Fail

Our breathing rate is regulated through a feedback mechanism. Too much carbon dioxide in the blood, or too little oxygen, and the brain stem commands the diaphragm to accelerate breathing. Once the levels are back to normal, the brain stem receives this feedback and slows breathing down again.

Now, Jacobs asks, imagine an impossible creature: ten people, all doing their own thing, but whose breathing is somehow regulated by a single brain stem. The feedback the brain stem receives is a consolidated average of everyone’s carbon dioxide and oxygen levels, and the breathing rate the stem decides on is applied to all ten people, regardless of whether they’re sleeping or playing tennis.

This, to put it mildly, wouldn’t work.

This creature is an analogy, representing a nation. The ten people are its individual cities, and the breathing rate is the cities’ economies. If it sounds like a stupid analogy, that’s because it is: “I have had to propose a preposterous situation,” writes Jacobs, “because systems as structurally flawed as this don’t exist in nature; they wouldn’t last.” Nor do they exist in machines we design; they wouldn’t work. But “nations, from this point of view, don’t work either, yet do exist.”

The feedback mechanism that fails to work properly in a nation is currency. A currency always fluctuates according to the exports and imports of the area where it circulates. Let me use the Republic of Venice and its ducat as a toy example, because the coins look nice:5

Whenever Venice produces something (like salt) and sells it abroad, foreigners need ducats to buy the exports, so the demand for ducats increases. When Venice buys something from abroad, it needs to use foreign currencies, so the demand for ducats decreases. Add up everything that Venice exports and imports, and you get either a trade surplus (more exports than imports) or a trade deficit (more imports than exports), which determines the value of the ducat relative to other currencies.

In both cases, a negative feedback loop restores balance over time, just like our brain stem does with carbon dioxide levels. A trade surplus, and therefore a strong ducat, means that when foreigners want Venetian salt, it’s expensive. So Venice’s exports decrease, while imports increase, since Venetians can use their valuable ducats to buy stuff cheaply from abroad. Conversely, a trade deficit makes exports a bargain for foreigners and imports expensive for Venetians.

This feedback loop is great. It’s exactly what a city needs to trigger the crucial import replacement process. When exports decrease and a trade deficit begins (maybe because Constantinople found a cheaper source of salt somewhere else), the weak ducat means that Venice is less able to afford the resources and manufactured goods it used to import. The people of Venice don’t want to have less of those goods, though, so they figure out ways to produce some themselves — that is, they do import replacement. Later they will be able to export the output of the newly expanding industries too, strengthening the ducat and continuing the cycle.

Currencies, Jacobs explains, function as automatic tariffs (to protect local industry from foreign imports) and automatic export subsidies (to encourage local industry to export). They are “automatic” because of the feedback mechanism. Just like an accelerated breathing rate, they take effect exactly when they are needed — and no longer.

… Or so they should, except that import replacement, as we discussed, is a city process. Whereas most currencies are national or supranational. National currencies work well for city-states, like the Republic of Venice or today’s Singapore. But in large nations, which, remember, are not the fundamental unit of economic life, they mess everything up.

Take a city like Detroit. When Detroit’s exports (primarily cars) decrease, Detroit gets no feedback about this, because its currency is the United States dollar, and the United States dollar’s value depends on much more than Detroit. It depends on other cities whose foreign exports might be increasing at the moment. And on rural regions that are selling resources like oil abroad. Also, trade between Detroit and other cities that use the United States dollar — i.e., American cities — is structurally unable to provide any feedback whatsoever. So Detroit doesn’t get the signal that it should buy less stuff from other cities and replace the missing imports with local production. Instead, it just declines.

Jacobs hypothesizes that this issue of national currencies is at the root of every large country’s economic troubles. It is why nations and empires always centralize everything into one large city, whether that’s Paris, London, Tokyo, or Toronto, or ancient Rome: that city, being the largest, is simply the only one for which national-level currency feedback works fine.6

The rest of the nation or empire, then, declines. But of course, nations and empires don’t accept this. They care about the economic well-being of their peripheral regions, sometimes out of genuine concern for the people there, sometimes out of fear that they rebel or hold independence referendums. So nations and empires will embark on every possible solution to reverse the decline. All of their solutions will look like good ideas at first, and yet fail at helping the peripheral regions. Worse, these solutions will weaken the cities, thereby destroying the only real wealth of the country and bringing untold hardship for everyone. Eventually the nation or empire will disintegrate, as nations and empires always do, and always will.

Jacobs calls these false solutions transactions of decline. She identifies three types, and, content warning, you might not like some of them depending on your political sensibilities.

Sustained military production is a transaction of decline. Permanent military bases and garrison towns are a special kind of settlement: they import a lot and export nothing. Superficially, producing weapons and supplies for the military seems like a good deal for some cities — Jacobs gives the example of Seattle, which, before Microsoft and Amazon were a thing, depended mostly on making military aircraft. But because nobody in a military base ever tries to replace those weapons and supplies with their own production, the trade is sterile in terms of economic development. In a sense, the wealth is slowly “drained” from cities. Large empires are especially prone to this: eventually all of their wealth is destined to the military just to keep the empire together.

Maybe you’re a pacifist and are thinking, “well yeah, pouring money into the military is dumb, we should use the money to help people instead.” Well, Jane Jacobs has bad news for you. Welfare programs are also transactions of decline. They, too, drain the wealth away from cities. When the Canadian government takes production from the Toronto city region and redirects it to your choice of: 1) the poor province of New Brunswick; 2) unproductive retired people; 3) farmers who depend on agricultural subsidies, that’s production that Toronto could have exported to an economically dynamic city instead, fostering development in both. Poor regions on the receiving end might seem better off, but remember that they don’t develop from welfare: depending on the exact shape the aid takes, they become clearance regions, transplant economies, or artificial city regions.

The third transaction of decline is heavy trade between advanced and backward cities, especially on credit. Selling a helicopter factory to the Shah of Iran is fine if the Shah pays for it with oil, but if Iran buys the factory on a loan and fails to pay it back (as poor regions often do, and as Iran did due to the revolution), then that’s also wealth that is drained away from cities. Nor does this kind of trade help backward economies develop. You can’t replace imports from an economy that’s much more advanced than you are: the gulf is too great.

Let’s take a moment here to appreciate how Jacobs casually destroys ideas so many of us hold dear. Trade between rich and poor countries seems obviously good. Military production isn’t exactly popular, but most people agree we need it for peace. The world would be far less safe without the military-backed Pax Americana. And welfare programs! Who wouldn’t want to send help to the poor, the unproductive, the retired? It seems inhumane to say that rich countries shouldn’t redistribute their wealth to alleviate poverty.

Unfortunately, that’s exactly why these things are transactions of decline. They seem like obviously good ideas at first. But then they spiral out of control. The more military production you invest in, the poorer you become, and the more you need military production to hold the empire together. The more welfare you provide, the poorer you become, and the more you need welfare to alleviate that poverty.

Jacobs’s book, published in 1984, includes this sentence: “As this is written, French students are rioting because of curtailments of subsidies.” Well. As this review is written, in March 2023, French people are rioting because the government is pushing the age of retirement from 62 to 64. Once you start relying on transactions of decline, you can’t ever stop.

The Forbidden Solution

All empires eventually collapse. This is not what we would expect if empires were a good economic arrangement. If they only ever got wealthier and wealthier, they wouldn’t disintegrate into various separatist factions or end in foreign conquest. The first empire to form would have slowly absorbed everything else, and we would all be living good lives under the enlightened rule of the Sumerians or whatever.

But that doesn’t happen, because empires always milk their own cities until they become poor. Modern nation-states do the same. They accumulate stress by trying to hold themselves together, and then, one day, the stress is released all at once. Wars and revolutions galore. Most countries are born that way, like new stars formed in the aftermath of a supernova.

Peaceful separatism offers an alternative, Jacobs says — but only a theoretical one.

Jacobs shows us a glimpse of a world in which secessions would be “a normal, untraumatic accompaniment of economic development itself.” Regions would separate when they feel the need to, before decline has set in. “In this utopian fantasy,” she writes, “young sovereignties splitting off from the parent nation would be told, in effect, ‘Good luck on your independence! Now do try your very best to generate [or maintain, as the case may be] a creative city and its region and we’ll all be better off.’”

Can you imagine Canada saying this to Quebec? Or England to Scotland? Or China to Tibet and Taiwan? Yeah, me neither. That’s why it’s only theoretical and utopian. Jacobs knows very well that nations will never accept separatism as an option. And though the term “nationalist” has fallen out of fashion, almost all of us still think very much in terms of nations.

Even when separatism does seem grudgingly acceptable, I’d say that’s usually either because it’s an instance of decolonization (colonial empires are decidedly out of fashion) or for cultural, nationalistic reasons. Quebecois, Scottish, or Catalan separatists say that they belong to nations that are culturally distinct from Canada, the United Kingdom, or Spain. And they love their smaller nation just as much as others love the larger one. If any of these separatists got their way, we can be sure that the new nation of Quebec, Scotland, or Catalonia would then oppose further separatism in the strongest terms. When the American South seceded from the Union in 1861, the reaction wasn’t “good luck!” even though the Union was itself the result of a secession from Great Britain.

To separate for economic reasons seems forbidden. Unthinkable. For one thing, it would be selfish. If Catalonia left, the poor regions of Spain, which benefit from welfare financed in part by Barcelona, would suffer, which is obviously unacceptable to Spain. For another, it’s not guaranteed to work. Small countries and city-states can still adopt dumb economic policies. It can seem intolerably risky to go your own way, unless your region is already rich, in which case see the selfishness point above.

Widespread separatism also seems worse for solving large-scale coordination problems, like environmental issues, nuclear proliferation (and, perhaps, AI), or war. I suspect that Jacobs would agree with Nassim Taleb’s antifragility framing: it’s better to be in a constant state of mild disorder than to have apparent stability that hides stressors and ends in violent conflict. But that idea is not intuitive. Most of us would pick apparent stability over mild disorder.

I also suspect — and this is my personal take — that we dread the additional complexity of having numerous small countries. We look at a map of medieval Germany, like this one…

… and we think, thank goodness that Germany is unified now. So much easier to think about! Can you imagine if the Our World in Data charts had to show separate lines for the Electorate of Saxony, the Prince-Bishopric of Augsburg, the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg, and about 1,800 other semi-sovereign states? Can you imagine traveling around if each of them had its own currency?7

Jacobs stops shy of asking, in either book, the question that seems to be the logical continuation of her reasoning: should everything be a city-state? Should we encourage separatism until each inhabited place in the world is either a city or a city region with its own currency?

We can hazard a guess as to what her answer would be. She would probably say that there’s no need to upend everything right this moment. Just adopt an attitude of political openness and experimentation. Don’t try to hold together entities that don’t work that well. When separatist sentiment arises somewhere, you can argue it’s a bad idea, but don’t fight it out of emotion such as fear for your nation’s integrity. Eventually, things will settle — the regions that want to be city-states will be, and those that prefer to be united with others, for cultural or economic reasons, will stay that way. Unity has good PR and some genuine advantages, so there will still be plenty of it.

But maybe Jane Jacobs never asks this question because she knows it’s irrelevant. We just can’t help fighting for our big countries and supranational unions (like the EU), and too bad if they enter long periods of stagflation until they violently collapse. This might be the right time to mention that her last book, published in 2004, is called Dark Age Ahead.

IV. Something to Dislike For Everyone

Jane Jacobs’s most famous book is The Death and Life of Great American Cities. She is recognized as perhaps the most influential thinker in urbanism. She is credited with saving Greenwich Village and SoHo in New York City, and helping cancel the Spadina Expressway in Toronto. To this day people organize “Jane’s Walks” as a living memorial to her impact on cities.

But Jane Jacobs herself thought that her greatest intellectual contribution was not in city planning, but in economics. She thought that import replacement was her most important discovery, since it explained how wealth expands better than existing macroeconomic theories. She wrote multiple books that were explicitly about economics and was about to write another when she died, Uncovering the Economy.

I am not an economist, so I might not be qualified to make a judgment on this matter, but: it seems to me that there’s a discrepancy here. Jacobs is widely seen as a great intellectual, but her economic ideas don’t quite seem mainstream. I’d never heard of import replacement before reading her book. Why not?

The null hypothesis is that economists have examined her ideas and simply rejected them. There were some critical academic reviews of Cities and the Wealth of Nations when it came out, and more recently Tyler Cowen expressed his own mild skepticism. Some of the criticism involves the lack of quantitative data in her work, and her failure to think about issues of scale. The most obvious target, of course, is her city obsession: yes, cities are important, but they’re not the only economic phenomenon that matters, some would say. Perhaps Jacobs has overplayed her hand.

But there are other possible explanations for the discrepancy. One is that she was a woman and had no credentials, which made it difficult for (mostly male) professionals to take her seriously. We know this was true at the beginning of her career at least. It seems possible that even after she managed to establish herself as an original urban thinker, economists had trouble accepting that she could, with her lack of any college degree, come up with new insights in their field.

I doubt that’s really true today, though. We do take Jacobs seriously, and still read all of her books, which is more than we could say about most economists. Instead, I propose that the discrepancy comes from a darker place: in laboring to be comprehensive about cities and economics, she reached conclusions that most people don’t want to be true.

No matter your politics, there’ll be something for you to dislike in Jacobs’s work. For example, it’s pretty clear that she didn’t think the European Union was a good idea, so she probably would have supported Brexit. Brexiters might rejoice, except that a lot of them are British nationalists who certainly don’t want Scotland to leave the UK, whereas Jacobs would agree with that. Which would be great news to Scottish independentists — except that if a new separatist movement arose within Scotland, she’d also support that.

Jacobs’s ideas and grassroots activism in favor of small-scale, organic urban planning have come to be seen as left-wing — yet her criticism of national welfare programs wouldn’t make her out of place among hardcore right-wingers. Unless those right-wingers were military hawks, in which case they’d find no solace in reading Jacobs on military transactions of decline.

Writing during the Cold War, Jacobs criticized the Soviet Union for its incredible centralization of decision-making in Moscow. She rightfully predicted its collapse, making her an ideological ally of the capitalist West, right? Not so, since the United States is also, according to her, too centralized and in the early stages of decay. “Today the Soviet Union and the United States each predicts and anticipates the economic decline of the other,” she writes. “Neither will be disappointed.” Whether she was correct about the US is left as an exercise to the reader.

In any case, she did foresee, using her theory on cities, the decline of Japan. This must have been bold in the 1980s at the peak of the Japanese economic miracle, when there was a widespread trope that Japan would soon take over the world. Yet she was right: in 1991, Japan entered its “lost decade,” which soon became two lost decades, and then three. To be fair, she predicted the decline of all large-ish countries, so I wouldn’t mark her as a superforecaster or anything. Still, this puts in perspective the more recent trope that China is going to take over the world. No country, no ideology is safe from Jacobs’s prophecies.

Smaller ideologies aren’t spared, either. Effective altruism would probably seem totally mistaken to her, since at its core it promotes an inorganic, top-down transfer of wealth from prosperous cities to poor areas. Progress studies people think that technological innovation will solve economic stagnation, but she would point out how labor-saving equipment so often causes damage when it is introduced to regions that don’t benefit from the other city forces, like the Scottish Highlands or many of her other examples in Colombia, India, or the American South.

(This point would deserve an essay of its own, but reading Jacobs has made me a bit more worried about the “AI will take our jobs” thing. It’s clear that new jobs will appear, but when the technology city force from the San Francisco Bay Area reaches distant places with poor economies, which it will very soon thanks to the internet, the effects might not be very pleasant to see.)

Overall, the political ideology that might fit Jacobs the best might be… libertarianism? She’s not a big fan of large governments who make big top-down decisions, clearly. Yet I don’t get the feeling that this association fits all that well either. Jacobs doesn’t seem to be anti-government if the government is at the city level. I doubt she would have liked the kind of hyperfragmented world depicted in Snow Crash by Neal Stephenson. I also doubt she’d be impressed by cryptocurrency-backed “cloud cities” or fantasies of charter cities, none of which she would see as real cities in the sense of concentrated pockets of people who start replacing what they import with local production.

Jane Jacobs, in sum, was an archetypal accidental moderate.8 She took one idea very seriously — the idea that cities are fundamental — and explored its ramifications without caring in the slightest if it led to the “wrong” opinions, as her friends in 1980 Toronto must have thought when she wrote about Quebec. I don’t know if she went too far; I’m sure someone more qualified than I am can find flaws in that core idea or any of her other observations. But to me she sounds convincing, and her consistency is frankly admirable.

So, to end this review on a more review-y note, go read Jane Jacobs. Her books are a delight, with their elegant arguments and masterfully told anecdotes. Her predictions often take an air of doom, but she is also an optimist who offers constructive ways forward. She sets an example for all of us who care about getting the details right, no matter the credentialed experts, the current political climate, or the great theories of the past.

The exact resources don’t matter much for the argument, but a commenter pointed out that another major export of colonial Boston was furs.

Some readers have commented that ‘import replacement’ and ‘import substitution industrialization’ do, in fact, have to do with each other. True, but I did mean to put the distinction in strong terms because it seems to be a very common misinterpretation of Jacobs's ideas. ‘Import replacement’ according to Jacobs is something that happens, not something that you do, but people interpret her as suggesting that governments should take actions to do it, which as far as I understand is the opposite of what she says — as her discussion of disastrous import substitution in Uruguay makes clear.

What about the US? It is famously not centralized around a single mega city. There are many possible answers. My guess is that the centralization process takes time, even more so when a country is demographically and geographically large. The US is both young and big, so centralization is still far from complete, unlike in older European countries or a country with a smaller population like Canada. Another factor that may have slowed down centralization is having a well-functioning federal system. In Europe, Germany is one of the less centralized countries, and it is young (1871), big, and federal.

But we could equally say that the US is far more centralized today than it used to be. Most economic activity of significance happens in a handful of cities that each act as the center of their respective industries, such as New York for finance, San Francisco for tech, and Los Angeles for entertainment. Many other American cities that used to be of national or global importance are now merely regional. The centralization process is not complete, but it is well underway.

The obvious question here is: Since Quebec is still part of Canada 43 years later, did Jacobs’s predictions materialize? I didn’t want to discuss this in the essay, partly to remain anonymous during the contest, but there would be a lot to say.

Culturally, Quebecers still feel somewhat threatened and still worry about the decline of the French language. Quebec is still on the receiving end of equalization payments from the richer parts of the country, and is considered the poorest of the big provinces. On the other hand, the economy seems healthy by several measures, and Montreal as a city is doing pretty well, having recovered from the lull it was stuck into during the 1980s and 90s, though it’s growing more slowly than Toronto.

In retrospect this may be a dumb example, because the ducat is not a fiat currency. Its value is determined by the gold it is made of, so it wouldn’t fluctuate all that much since other cities also use gold. This is my fault, not Jacobs’s: I’m the one who was trying to come up with a toy example to help myself understand better.

There is a field of research in economics called optimum currency areas, which tries to determine what areas (supranational, national, subnational) should have their own currencies. It dates from the 1960s, but as far as I know Jacobs didn’t engage with it. It seems reasonable to count this as a flaw on her part.

Actually, it wouldn’t be that bad! Jacobs pointed out — in 1984 — that computers were making it very easy to deal with multiple currencies. It has only gotten easier since then, so the convenience argument against multiple currencies is now rather weak.

I really do mean “accidental moderate” in the sense presented by Paul Graham in the linked essay, i.e. someone whose independent thinking puts her roughly in the center of her society’s politics “by accident.” That doesn’t mean Jacobs is necessarily a moderate in the narrower sense of any specific country’s politics.

Wonderful review. The economist Ed Glaeser wrote 2 interesting papers that bear on some of the points you discuss:

Re: Boston (footnote 1), its ability to maintain its prominence over the centuries has been due to exactly the kind of trade dynamics you mention: https://www.nber.org/papers/w10166

Re: American centralization (footnote 3), one major reason why the economic fortunes of Chicago and Buenos Aires diverged so dramatically during the 20th century after being very similar in the 19th was that BA was also the political capital whereas Chicago was insulated from political shocks: https://www.nber.org/papers/w15104

Incredible review. I wonder, does this concept of import replacement apply to online communities and international corporations as well? Could this concept be the foundation of a generalized theory of the rise, decline, and fall of units of economic activity beyond cities?