A little more than a year ago, I wrote about the proto-industrialization of Mughal Bengal. I had been intrigued by that word, proto-industrialization, and the suggestion that if things had happened a bit differently, the Industrial Revolution could have happened not in Europe, but in Asia. I dove deep into the topic, and learned a lot about the history of technology, economics, and the Indian subcontinent.

But Bengal is not the only non-European region to have been called proto-industrialized, i.e. having a highly developed handicrafts economy. There is at least another, a major civilization that developed advanced technology and an early version of capitalism long before these things appeared in India or Europe: China, specifically under the Song dynasty, between 960 and 1279.

Like I did in the Bengal post, I want to explore Song China and its technological and economic achievements. My goal is to gain an understanding of how a proto-industrialized society could arise, and what it looked like, and then ask the difficult but tantalizing counterfactual question: could the Industrial Revolution have happened in medieval China? That’s the kind of question that historians hate, because they study what actually happened, not what could have happened. Fortunately, I’m not a historian, so we’re at full liberty to ask the question anyway.

First (I) we’ll contextualize Song China, then (II) we’ll ask how it managed to develop a flourishing economy, (III) look at a bunch of their cool futuristic tech, and finally (IV) examine some hypotheses for why industrialization didn’t take off like it did in 18th-century Great Britain.

I. The Song in Context

If you’re like me (i.e., fully Western and decidedly not Chinese), the most you ever learned about Chinese history in school is a footnote about Mao Zedong and the establishment of communist China. So it seems useful to take a moment and cover the rest.

Chinese history is typically divided into dynasties, as well as a few intermediate periods of disunity. The full list of Chinese dynasties since the founding of the first Chinese states 4,000 years ago is long and complex and can be viewed here, but let’s just focus on the few most important ones in order to understand where the Song dynasty fits in.

Skipping the ancient period and starting from the unification of China:

Qin dynasty (221–207 BC) and Han dynasty (202 BC–220 AD): Qin is the smaller Chinese state that first unified all the smaller Chinese states into an empire, but it didn’t last long and control soon fell to the rulers of the Han state. The Han dynasty is the first golden age of unified China; it lasted four centuries and gave its name to the Han ethnic group. This period corresponds fairly well to the hegemony of Rome in the West.

Six Dynasties (220-589): a collective term for a turbulent period encompassing the Three Kingdoms, the Jin dynasties (Eastern and Western), the Sixteen Kingdoms, and the Northern and Southern dynasties, altogether comprising about 30 distinct dynasties — I guess the “six” refer to the major ones, like the Jin? — none of which matter much for our purposes. Corresponds to Late Antiquity and the beginning of the European Middle Ages.

Sui dynasty (581–618) and Tang dynasty (618–907): a Qin-Han kind of situation where the Sui reunify China and then lose it — in this case due to the incompetence of Emperor Yang, “one of the worst tyrants in Chinese history.” The Tang emperors take over and go on to preside over one of the greatest golden ages of China, at a time when the West was struggling to reestablish advanced civilization during what people still call “the Dark Ages.”

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907-979): yet another period of disunity with too many dynasties to keep track of, but this one is important because it allowed the rise of the Song, who gradually took over most of the others and unified China once again.

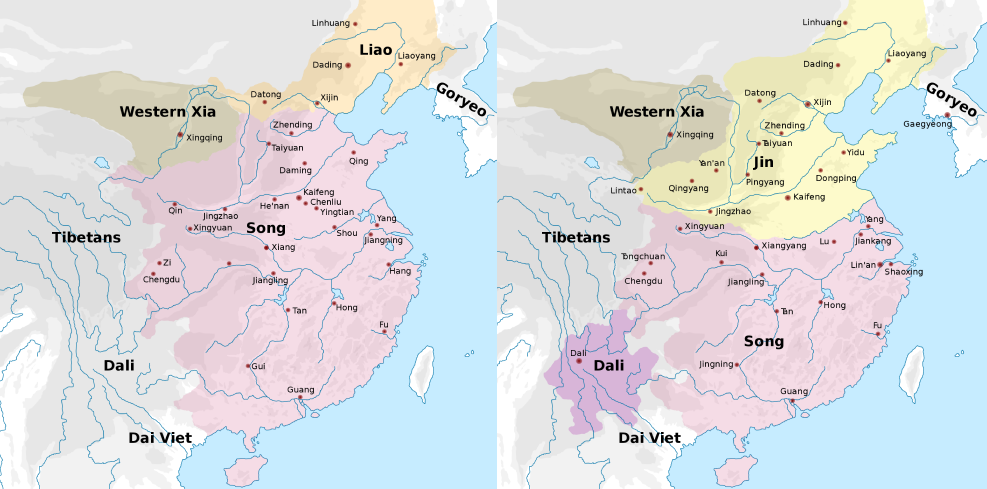

The Song dynasty (960-1279) is conventionally divided into Northern Song (960-1127), when it ruled all of China except the far north; and Southern Song (1127-1279), when its northern half was conquered by a dynasty called Jin (not the same Jin as above) and then the Mongols. Corresponds to the High Middle Ages in Europe.

The Mongols! The Mongols are pretty famous for conquering a lot of land. Like, a lot. Some of that land was taken from the Jin in Northern China, after which the Mongols coexisted with the Southern Song for a few decades, after which they said “what the hell” and conquered them too. China was therefore unified under what was called the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), ruled by a Mongol elite that was rapidly becoming sinicized. This is still the High Middle Ages in Europe, and happens to be when Marco Polo visited the Mongol/Chinese imperial court from Venice.

Ming dynasty (1368–1644): as the Mongol Empire in general and the Yuan dynasty in particular crumbled, the Ming took over and established the last dynasty ruled by the ethnic Han people. In Europe, the Renaissance and Age of Exploration were underway, which led to regular contact between China and the West.

Qing dynasty (1636–1912): this dynasty was founded following conquest of the Ming by a northeastern Manchu clan called (yet again) the Jin dynasty. It comprises a great golden age called the High Qing era, spanning the full 18th century. But it is also when the country failed to industrialize like Europe, leading to the century of humiliation: the 100-year period starting around 1839 when China was dominated by European powers and Japan.

Post-imperial China starts in 1912 at the fall of the Qing monarchy and the establishment of the Republic of China, which is then overthrown (outside Taiwan) by communist leader Mao Zedong to found the People’s Republic of China in 1949. It is only in the 1950s, almost exactly a thousand years after the start of the Song dynasty, that China begins industrializing in earnest to become the manufacturing powerhouse that it is today.

Alright, that should be enough context. Before we move on, I’ll note that this timeline raises a couple of interesting questions. What was special about the timing of the Song that allowed them to develop advanced technology? Were the Mongols responsible for the destruction of the Song industry and economy? Why did the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties fail to (proto-)industrialize to the same extent as their Song predecessors did, especially considering that they had contact with Europeans? And why were so many minor dynasties called Jin??

Let’s start with the first of these. What happened when the Song dynasty took over, allowing them to become the wealthiest economy the world had ever seen so far?

II. What Made the Song Top the Charts?

It seems pretty tricky to answer this question — the sources that came up in my (amateur) research mention a few things, but don’t really converge on a single cause. But we can come up with a reasonable answer by examining a few interdependent trends that unfolded during the Song dynasty.

First off, massive population growth. Until and including the Tang dynasty, the Chinese population fluctuated between 37 and 60 million, but it managed to escape the Malthusian trap and grow sustainably during the Song/Jin era, reaching 100-140 million. This was apparently due in large part to a geographic shift. Before, most of the Chinese population had been concentrated in the north, around the Yellow River; during the Song period, the northern population did grow (creating multiple million-people cities), but the south grew even faster, eventually making up the majority of China for the first time.1

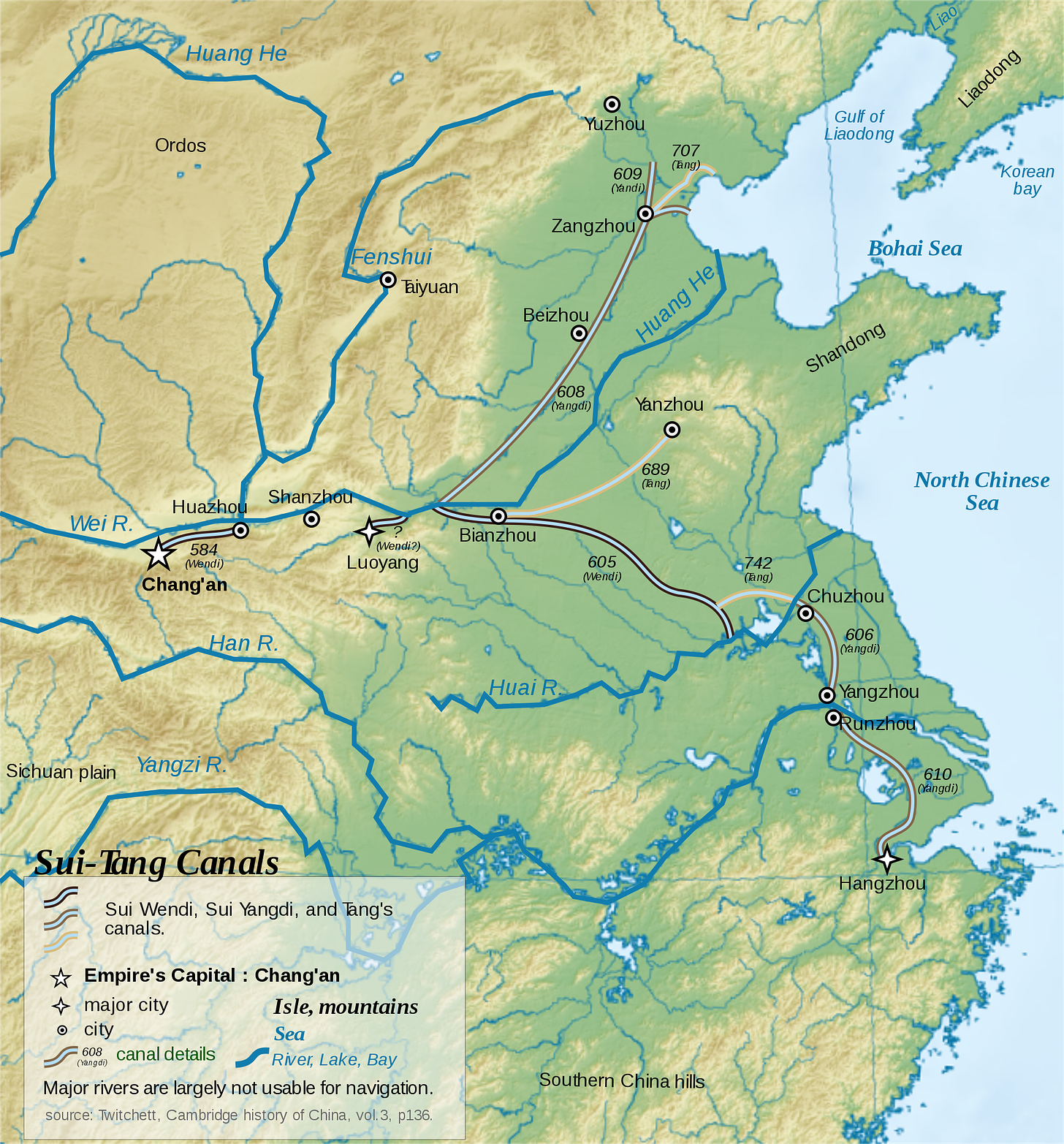

A contributor to this growth seems to have been new, early-ripening varieties of rice, introduced from Southeast Asia, called Champa rice. Another is improved means of communication and travel between the north and south, such as the Grand Canal:

The Canal is an achievement of the Sui and Tang dynasties, but my understanding is that it increased movement between northern and southern China well into the Song era, at least until part of it got destroyed during the Song-Jin wars. (The Yuan emperors would eventually restore it.) It allowed the rice to move north, and people to move south.

Was population growth a cause or a consequence of economic development? Both! The increased rice yields allowed more people to specialize into cash crops (like tea and silkworms) or handicrafts (like porcelain), as opposed to subsistence farming, leading to a larger market economy and urban population, leading to more innovation… which allowed for further increased agricultural yields and demographic growth. Everything in these kinds of questions depends on everything else, which is why it’s hard to reach definitive answers.

Another clear factor is policy reform. Although I haven’t been able to find an authoritative source, I’ve seen some hints (especially in this article) that the first two emperors of the Song dynasty, brothers Taizu and Taizong, implemented a number of beneficial policies, including limiting taxes on land in favor of taxes on trade — which meant that the state had an incentive in encouraging more trade. This is a little bit counterintuitive and I don’t have a great source to back it up,2 but at least it seems clear that the Song had advanced tax policy and derived more revenue from non-agricultural taxes. In general, the government deregulated commerce overall, except for a few state monopolies on key resources such as salt.

I’ve also seen some mentions of Wang Anshi, a chancellor of the empire who looked like this:

Wang Anshi was embroiled in a rather interesting political feud, described in delightful detail here. Rising to the post of what is essentially prime minister, he rejected the establishment of his time (stodgy, conservative Confucian scholars) and came up with wide-ranging New Policies that sought to grow the economy. Actually, it might have been him who switched the focus to taxing commerce rather than land, I’m not sure.

Wang Anshi’s policies would constitute an elegant answer to the question of Song economic development. Unfortunately:

He held power in 1069-1076, more than a hundred years after the beginning of the dynasty, but the trends started earlier.

All the stodgy, conservative Confucian scholars at the imperial court hated him and reversed his policies as soon as they could.

Regardless of the actual government policies, they existed in a context of decentralization. It seems that the Song empire relied on a reasonably autonomous gentry class more than imperial officials for local regulation, unlike the earlier Tang dynasty, when the emperors tried to control business in heavy-handed, top-down fashion. (This is … quite reminiscent of China’s current tug-of-war between central planning and free markets!)

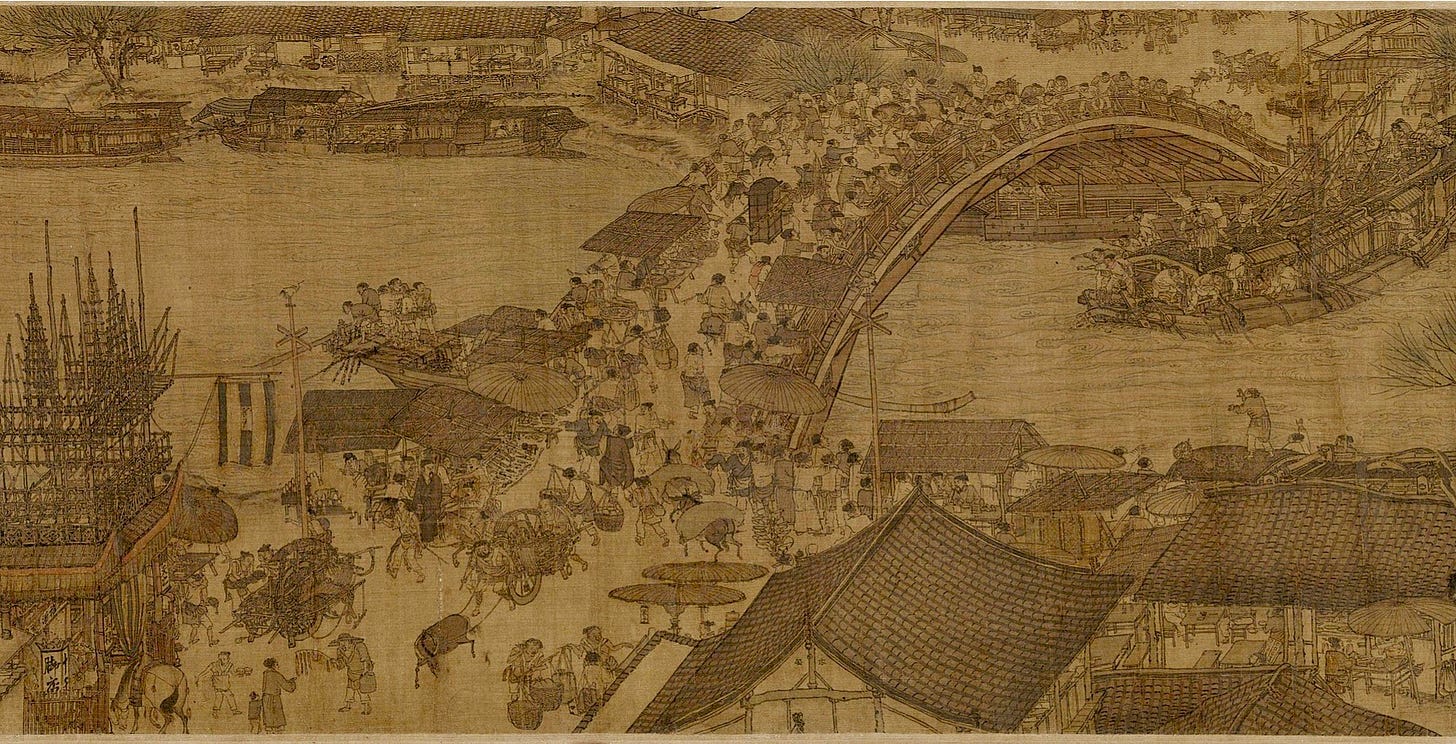

Also — remember the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period of disunity from the timeline? Despite a connotation of chaos and war, it was actually a very innovative era, partly because, like in Europe, many states were in competition with one another. When the Song won and (partially) centralized authority again, they at least inherited some of that decentralized prosperity.3 Combine that with the growing population, developing urban centers, and the emergence of cash crops and handicrafts, and we get a market economy unlike anything China had seen before. Quite literally, too: physical markets played a large role in cities.

The economic factor that we haven’t examined in detail yet is innovation, which is, of course, also both a cause and consequence of the rest. The Champa rice, and a number of associated developments in agriculture, are a clear example. That’s what we cover in the next section.

III. Song Tech

The Four Great Inventions

China likes to say it has “Four Great [Things]”, like the Four Great Classic Novels (all post-Song dynasty). The Four Great Inventions, however, are a Western concept: they’re an idea from Francis Bacon, who thought that printing, gunpowder, and the compass were the three Chinese innovations that “have changed the appearance and state of the whole world“.4 Later, Karl Marx would wholeheartedly agree, saying that they’re “the three great inventions which ushered in bourgeois society.“5 Later still a sinologist would add paper to the list.

All of these inventions predate the Song. But all of them were improved by the Song.

In printing, the Song era saw the invention of movable type, in which small components made of porcelain (at first), wood, or metal, can be assembled to make a page and print it many times.

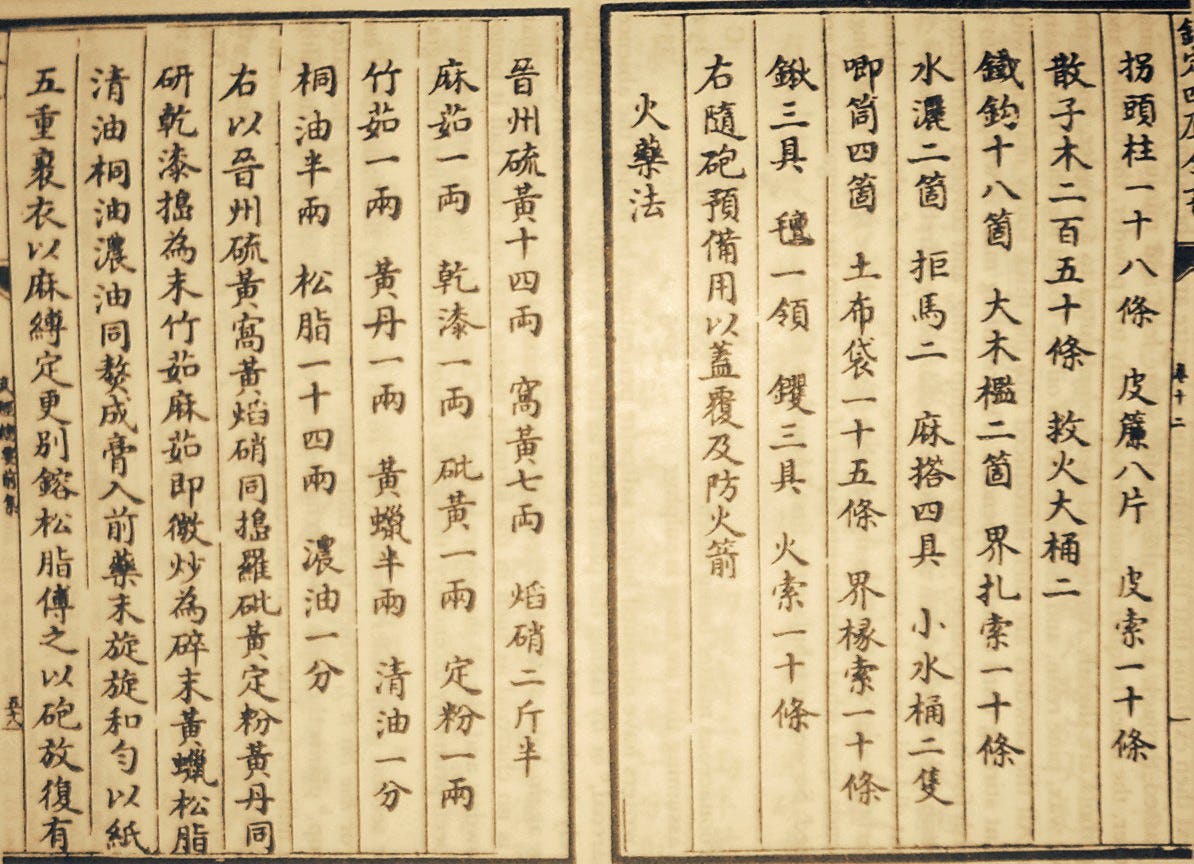

Gunpowder was invented by Tang-era alchemists who were trying (obviously) to invent an elixir of immortality, but it is under the Song that it became widespread in warfare. They made all manners of explosives and projectiles: bombs, grenades, cannons, rockets, fire arrows, and fire lances. Also, fireworks!

Meanwhile, the magnetic compass had been invented by the Han dynasty, but they used it only for divination, presumably like one of those stupidiotic fortune-telling magnetic toys you can get on Amazon.6 The Song Chinese were the ones who realized it could be used for military and maritime navigation.

As for paper, it’s also a Han-era invention, but its manufacture became so cheap and widespread that it was used for things like toilet paper and tea bags, plus what might be the Song’s most significant invention, namely:

Paper money

Today’s Chinese banknotes look like this:

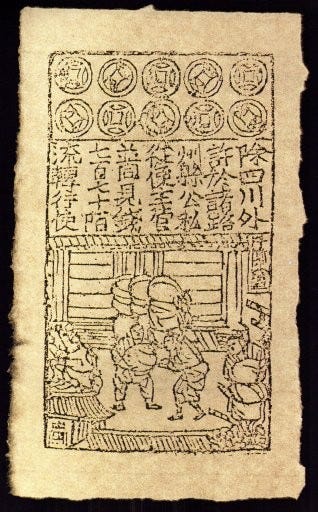

Song-era banknotes looked like this:

They were the first banknotes ever. Earlier Chinese dynasties and other states, like Rome, had sometimes made use of written notes to promise repayment, but the Song were the first to implement a full paper currency system controlled by the central government, complete with seals used to ensure the banknotes were authentic. Eventually they even built large printing factories, with hundreds of workers, to continuously make banknotes on a large scale.

Eventually they caused an inflationary spiral — the Song dynasty was also the first government in the world to experience the negative consequences of “printing too much money” — but it seems pretty clear that the paper banknotes are at least a sign, if not a cause, of the sophisticated economy that was burgeoning. I understand that they made lending money much more convenient, increasing access to credit.7

Relatedly, the Song were among the first to have joint-stock companies in which merchants could invest and share profits.

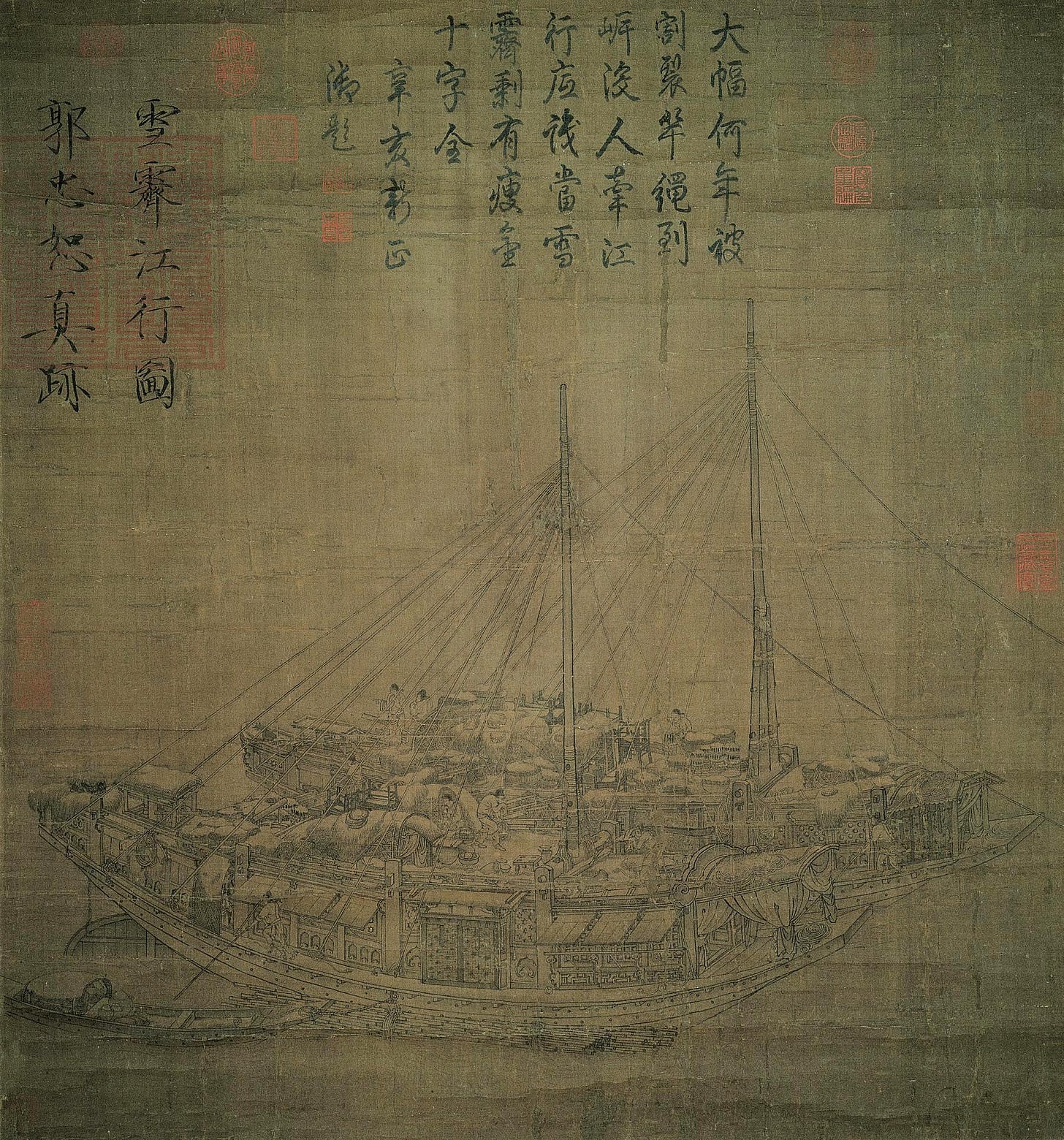

Ships

Ships crop up all the time when discussing (proto-)industrialization, because they used to be the most efficient way, by far, to move stuff around. The Song dynasty is no exception:

Equipped with their magnetic compasses, the Song sailed the seas all the way to Egypt; their shipbuilders knew of bulkhead watertight compartments, of lug sails, of drydocks, and a variety of other naval vocabulary I know too little about to list here. Arab travellers like Muhammad al-Idrisi wrote of the enormous amount of merchandise being transported by the Chinese junks: iron, swords, silk, velvet, porcelain, much of which was destined to foreign markets in India or the Middle East.

Machines

But as important as they are, ships alone do not make an Industrial Revolution. Ultimately, you want machines — machines to free humans from labor, machines to make productivity soar.

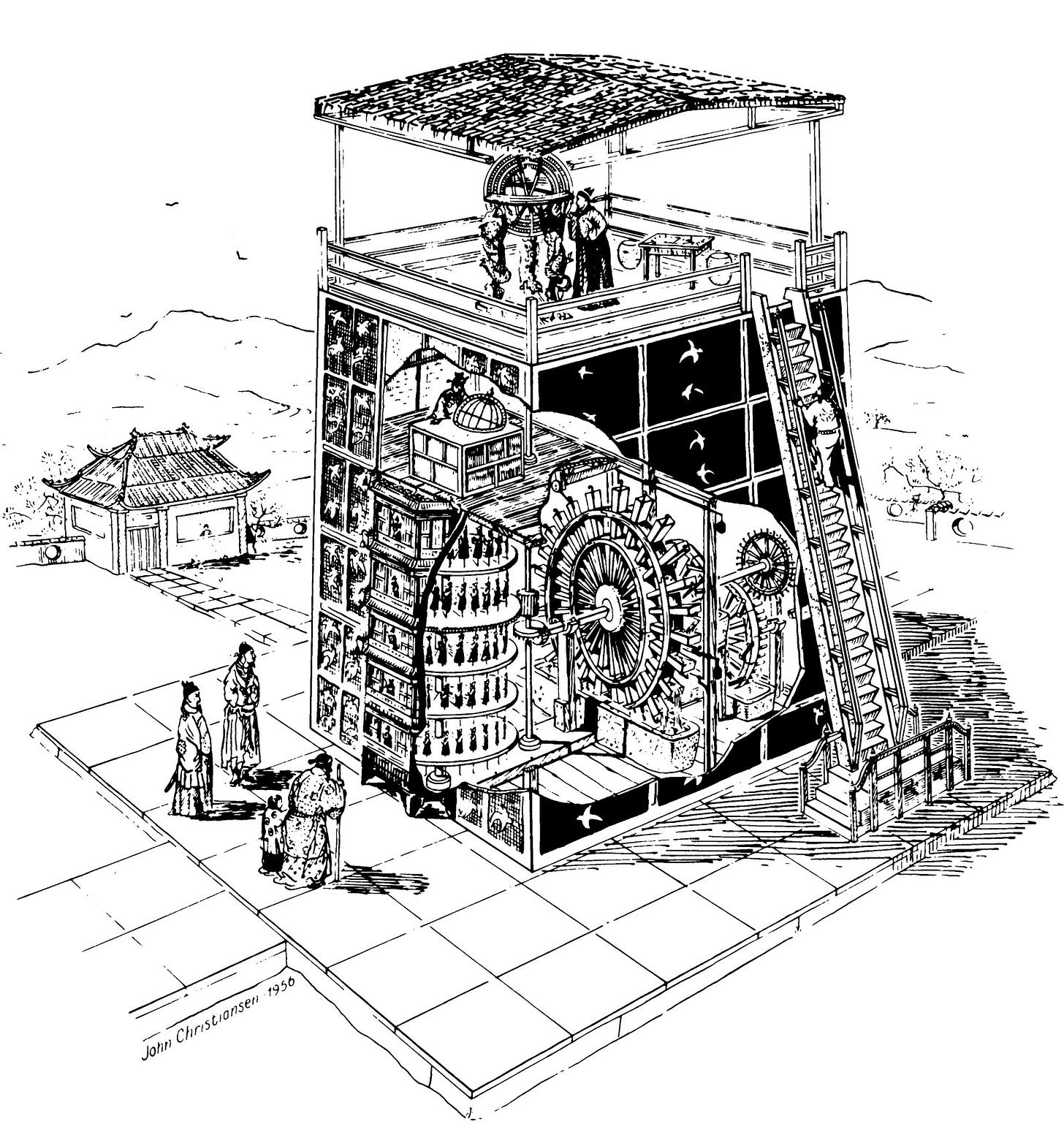

Consider the polymath Su Song’s clock tower:

The Song were clearly quite advanced in the mechanical arts. They could spin textiles:

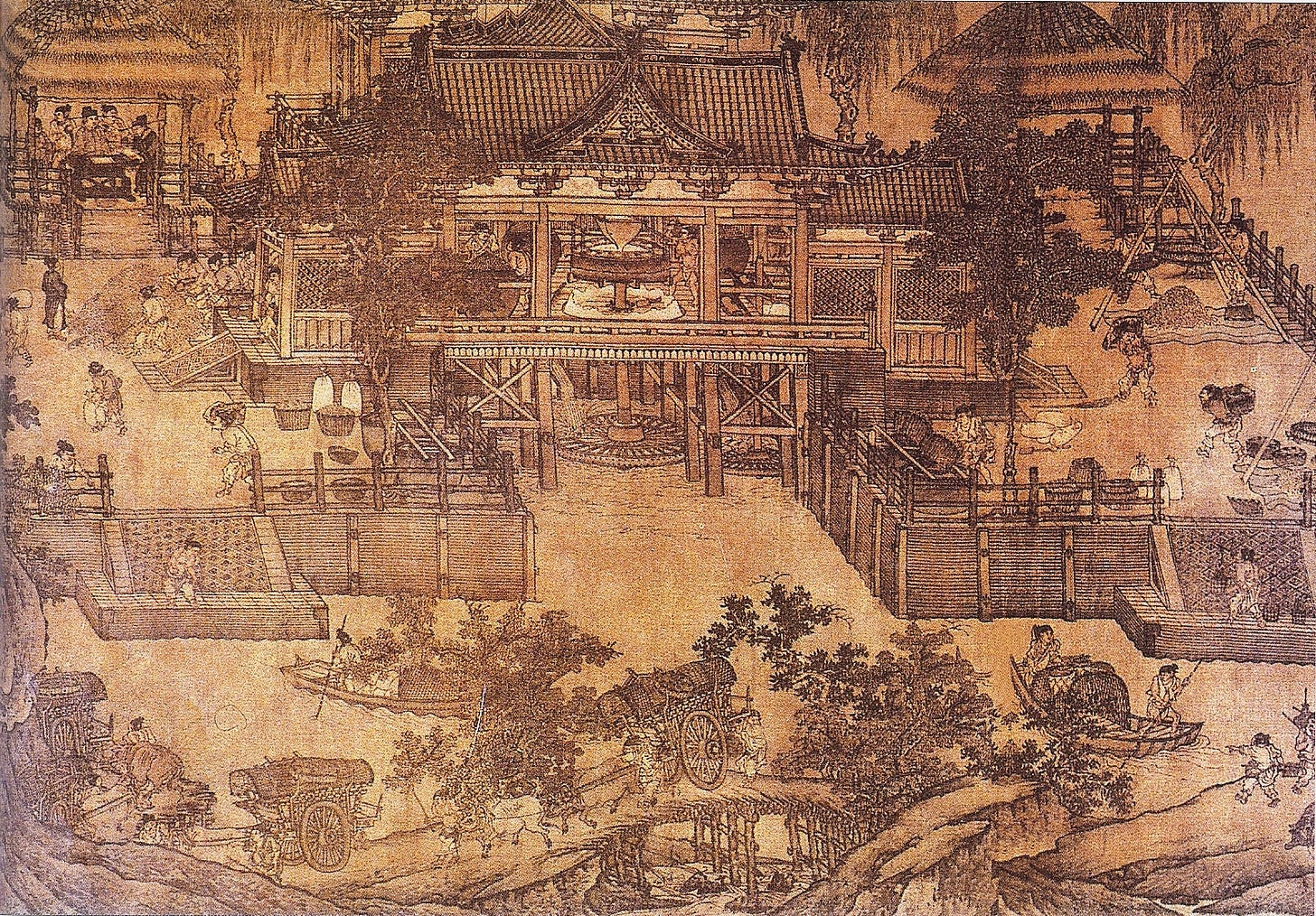

They could harness the power of the wind and rivers and build large, elaborate mills:

They had fairly extensive facilities to process silk:

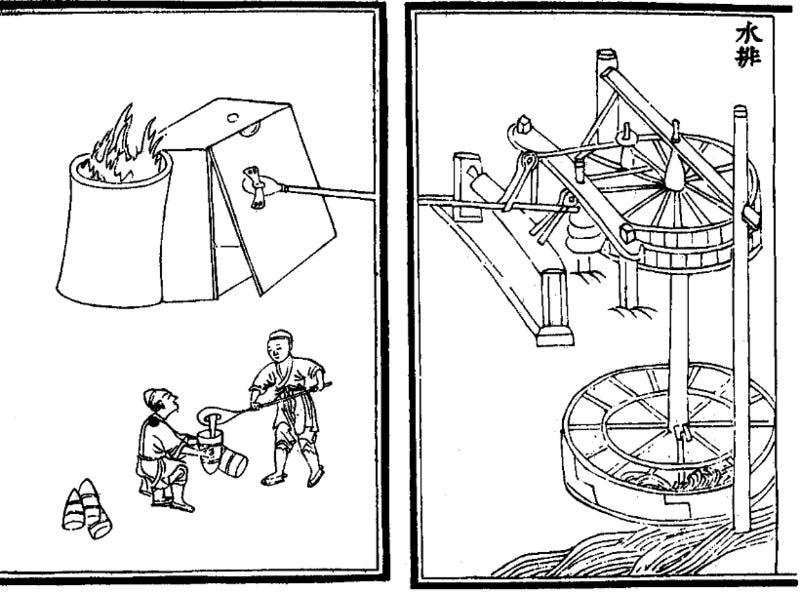

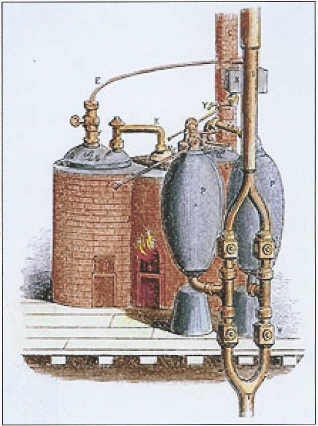

They also had water-powered bellows for blast furnaces, and therefore an extensive iron and steel industry:

Metallurgy

Speaking of metal, the Song were high achievers in this field too. They invented early versions of techniques that would be fully developed only during the British Industrial Revolution, like the Bessemer process to purify iron and make steel. They also produced an estimated 125,000 tons of cast iron per year around 1078, more than the rest of the world put together and far more than the Tang dynasty ever did.8

The scale of the blast furnaces they used to smelt iron and steel was such that it led to massive deforestation in northern China, for the purpose of making charcoal, although they eventually discovered they could use bituminous coal instead. The iron and coal production during the 12th century was apparently comparable to Great Britain’s during the 18th.

The copper industry was also well-developed, providing the many coins that were necessary to fill the needs of the expanding economy, at least until they were partially replaced by paper banknotes.

We’ll stop here, otherwise we’d be here all day; but I do want to mention that in addition to the above technologies, there were many more achievements in astronomy, civil engineering, architecture, agriculture, and even archeology. It’s hard to skim a page like Science and technology of the Song dynasty and not be awed at the advancement that Chinese civilization reached a thousand years ago.

IV. Why Was the Song a One-Hit Wonder?

So, what happened? It’s clear that many of the ingredients of industrialization were present in medieval China: textile machinery, advanced metallurgy, ships and waterways, a printing press and the dissemination of new ideas, and the beginnings of capitalism. Yet the progress stopped, and stopped so hard that China would stagnate for centuries. What happened?

I knew when I started writing this post that it would be a tricky question. I’m not sure I had realized just how tricky, though. In some sense, it might be one of the most important questions in world history: had the Great Divergence between Europe and Asia not happened, the present would look very different indeed. Yet we can do little more than list hypotheses, and then combine them into whatever narratives suit us.

Hypothesis 1: The Mongols!

They’re the obvious suspect, aren’t they? The story writes itself: an advanced civilization thrives in peace, until the unruly barbarians break in from afar and wreak destruction across the land. You’re thinking of Rome falling to the Germanic peoples; I’m thinking of India falling to the British India Company.

Certainly the decades of war between the Song and the Mongols, ending with total conquest, took a large human and economic toll. The population decreased by quite a lot. The Black Death, in the mid-1300s, added to the damage. Some of the policies picked by the Mongol emperors during their century of rule were detrimental, like official discrimination against Southern Chinese9 for having resisted them so long. Many of the flourishing areas were in the south, remember, so this would have slowed progress down. Also, the Yuan levied heavy taxes and established new state monopolies.

On the other hand, the Yuan dynasty wasn’t a particularly dark age in Chinese history. The Song market economy survived, and even thrived in some new ways: the humongous extent of the Mongol Empire allowed Chinese products to find buyers all over Asia. There were new inventions and artistic developments. The Yuan emperors themselves adopted Chinese culture and many of the existing institutions.

My takeaway is that the Mongol conquest obviously disrupted China, and in that way made industrialization less immediately likely, but it didn’t fundamentally alter the trajectory of Chinese civilization.

Hypothesis 2: Contingent factors, a.k.a. random shit

The historian Kenneth Pomeranz believes10 that China’s failure to industrialize is primarily due to not harnessing fossil fuels. As we saw, the Song did figure out they could exploit coal for their blast furnaces, but unfortunately the coal mines were in the north. Which is the area that was lost to the Jin dynasty and then the Mongols. Thereby destroying much of the coal mining industry.

Also, the coal mines in Britain were wet, providing a great use case for steam engines, which were so inefficient at first they would have been useless if not for pumping water out of coal mines where you could literally pour coal as you wanted into the engine. But Chinese mines were dry, so they couldn’t invent steam engines.

My understanding is that this overemphasizes the importance of coal and steam — today’s historians think they weren’t that critical to the British Industrial Revolution. So that would hardly be a good explanation for the Chinese Lack of Industrial Revolution. However, it’s a good example of a plausible contingent reason. It’s possible that many puzzle pieces had to be assembled for industrialization to take place, and one of them just happened not to be in the right place and time during the Song or later eras.

Hypothesis 3: No need for innovation, due to the high population

This is a very “economic historian” kind of argument, and I may not have understood it fully, but basically, some think that China’s large population prevented it from seeking alternatives to just hiring a lot of people do work.

As a Reddit r/AskHistorians answer puts it, “Even at the height of the Song, it was cheaper to employ more manpower . . . than it was to develop and then deploy labor-saving mechanization.” Wages were generally low, and energy costs high, so using energy to replace labor didn’t make sense — unlike in 18th-century Great Britain. Mark Elvin also suggested in the 1970s that the large population prevented the accumulation of capital that could have spurred the necessary investment. China was in a high-level equilibrium trap: supply and demand were too well matched.11

I don’t think there’s a consensus around this explanation. For one thing, we can easily count a high population as a positive factor, leading to a larger market, more creative innovators, etc. For another, the population shrank during the Mongol era, partly due to war and partly due to the Black Death, so if a small population in need of labor-saving equipment were the key missing factor, you’d have expected the takeoff to take place during the Ming dynasty. Instead what we see there is a slowdown.

Hypothesis 4: The Ming

We haven’t talked much about the Ming yet. Here is their founder, the Hongwu Emperor:

The Hongwu Emperor was originally a peasant, then a monk, and then a rebel against the Yuan dynasty who rose to warlordship and then declared his own dynasty. Favoring farmers over merchants, he adopted policies to curb trade, and made China an isolationist state under the Haijin doctrine, restricting foreign commerce to a handful of state-led missions. This predictably (and deliberately) hampered growth, which ground the wheel of progress to a halt.

And so we get explanations by libertarian writers like Matt Ridley, such as:

The Ming were quite the opposite of the Song. They wanted tight, centralized control of everything. They literally controlled where you could travel, and they needed a report from every merchant on how much stock he held in his warehouse at regular intervals. This was a recipe for killing innovation.

Or, from the Foundation for Economic Education (also libertarian):

Long-distance trade was discouraged, as was overseas trade, and after 1430 all trade by sea was stopped. In general the Song policy of relying on taxes on trade and encouraging it (to bring in revenue) was reversed, and the traditional agrarian taxes were restored. The Ming and Qing sought to make peasant farmers the basic unit of society; free movement was stopped. Several technologies were abandoned or deliberately abolished. The Ming encouraged the formation of large regional merchant cartels, which were favored by the state and given monopolies over key commodities such as lead, iron, and salt. In general, the policy was to discourage and regulate innovation and to promote social stability at the expense of growth.

I initially found these fairly convincing, and I do think there’s some truth to it — the Ming did adopt some pretty bad economic policies, at least from a pro-progress perspective. (It’s important to remember that their goal was stability, not growth, and they did quite well at stability for centuries!)

On the other hand, the story is a bit too cute. In fact the restrictive policies of the Hongwu Emperor were either reversed soon after his death, or were easy to avoid. There were smugglers aplenty to carry foreign trade. The state monopolies, which were a mainstay of Chinese imperial government since forever, were weakened and then abandoned, as was the organized system forced labor. Taxation overall was very light. In short, most of the Ming era was one of economic laissez faire.12

I don’t know how to reconcile these. The libertarian guys just seem plain wrong. If the Ming were more economically liberal than the Song, and yet innovated less, that’s not a knockdown argument in favor of economic liberalism. Maybe I should have focused my research on the Ming rather than the Song after all.

Hypothesis 5: The Qing

But of course there’s another dynasty down the line! The Qing, who ruled from 1644 to 1912, and whose first emperor looked like this:

The Qing were the ones who saw the Great Divergence between Europe and China really happen, when the British, armed with powerful steamships, invaded the Chinese to force them to trade. This became known as the Opium Wars, and the Chinese, equipped with firearms and swords from an earlier era, were soundly defeated.

I don’t want to dwell on the Qing too much, because we’re now quite far removed from the Song era. But it’s interesting to note that Kenneth Pomeranz, the historian I’ve cited above regarding coal, thinks the Great Divergence started only around 1700-1750. Under this view, the Song, Yuan, and Ming didn’t do anything particularly wrong, and it is only later that policy errors squandered China’s previous prosperity. It does seem like Qing-era markets and taxes were more or less a continuation of the Ming’s, though, so I don’t know.

Hypothesis 6: Some mix of religion / philosophy / culture

If deliberate economic policies don’t offer a clear answer, we’re left with cultural factors. Historians typically dislike invoking cultural factors, because they can explain anything. It’s too easy to say that the Chinese “didn’t have the European capitalist mindset” or whatever.

But culture is real, so it may be the correct explanation anyway. I’ve sure seen it crop up quite a few times, in different guises.

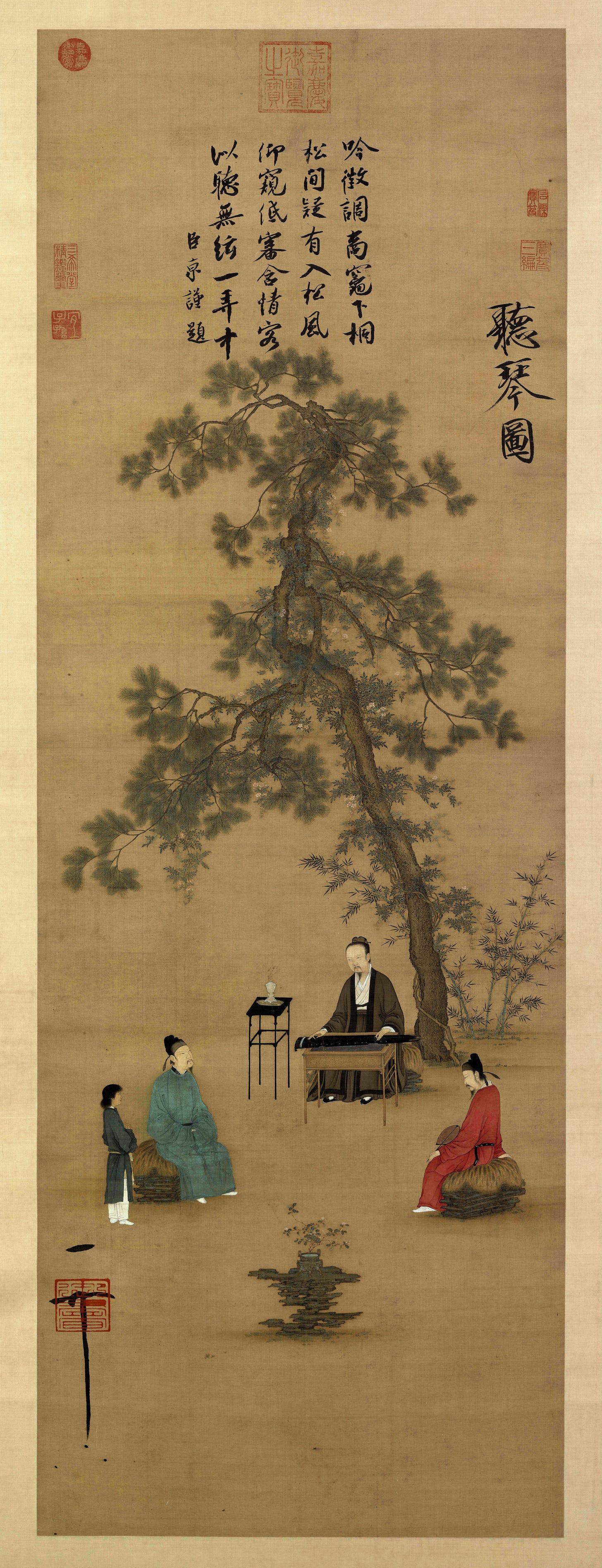

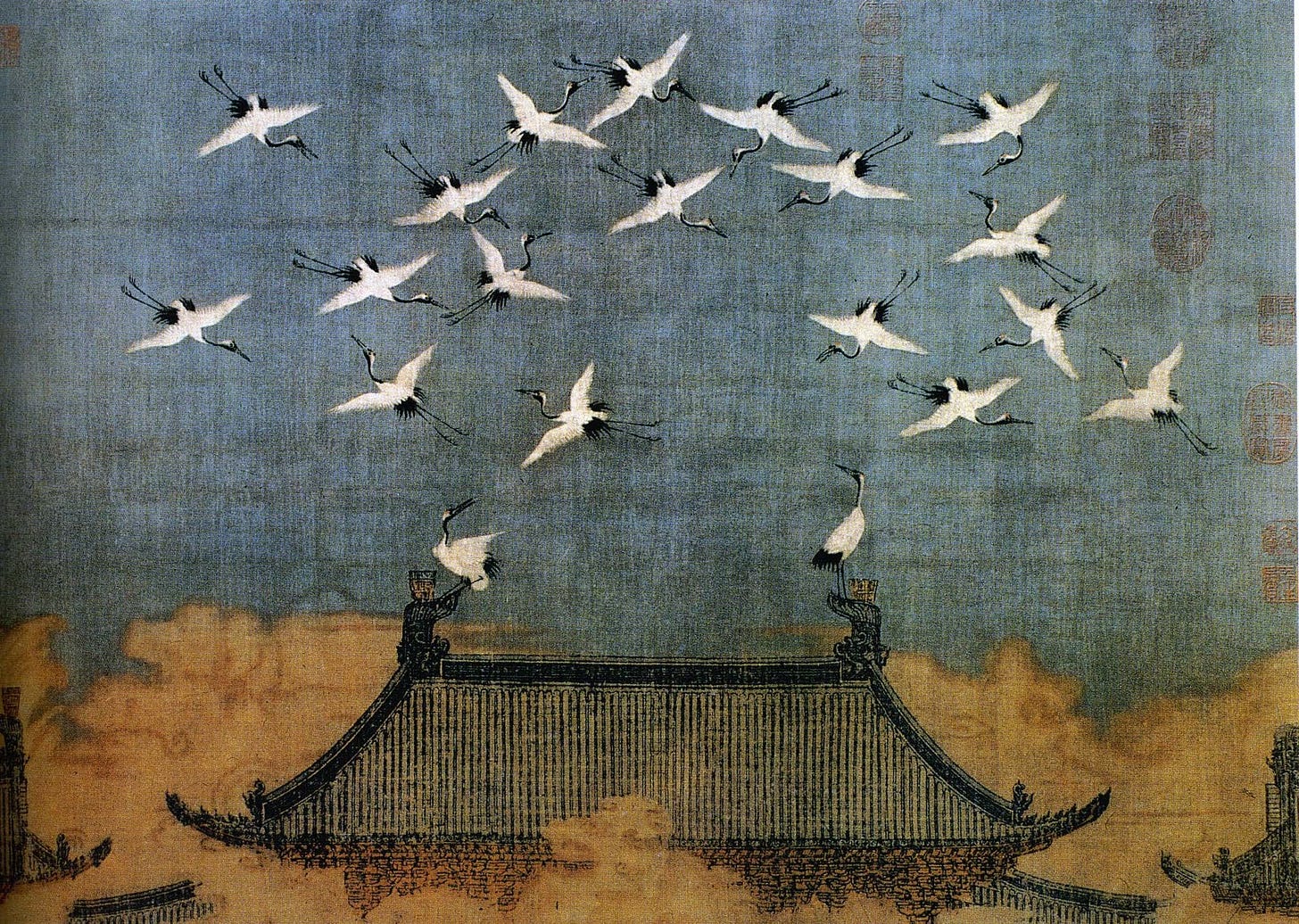

One is about religions or philosophies. Confucianism, the dominant ideology of China since ancient times, is often characterized as conservative and in favor of a strong state to supervise the welfare of the people. Taoism, meanwhile, is much more focused on intuition, and letting things happen. The parallel with central planning vs. markets is obvious. It may not be a coincidence that Taoism was flourishing during the Song dynasty, especially under Emperor Huizong. Or maybe it is a coincidence, since Confucianism was still dominant throughout the Song era — partly through Neo-Confucianism, a more modern synthesis that became popular at that time. Overall this is confusing and I remain fairly skeptical that this had a big direct importance.13

Another big part of imperial Chinese culture, which was influenced by Confucian thought, is its bureaucracy. The practice of selecting government officials through a gigantic examination system is nice, because it’s meritocratic, but it also not nice, because it selects for people who are good at passing exams by learning their classics, rather than creativity or heterodoxy. It’s possible that this system was a formidable invention during the Song era, when it became widespread, but then calcified into an engine of stagnation during the Ming and Qing dynasties.14

Ultimately, the main imperial Chinese cultural trait that everyone agrees on is their love of stability. The state was centralized,15 preventing internal conflict, and it was impervious to external threats (until it wasn’t). It didn’t care about the rest of the world; its long-distance sea expeditions in the 1400s had been canceled, perhaps for fear of their social consequences. Nothing ever really changed, because the Chinese didn’t want anything to change. They were like the civilizations of certain science fiction universes that manage to exist for thousands of years by restricting science, until advanced aliens appear and demonstrate the folly of that strategy.

That explanation is still a bit too cute for my tastes, but it probably is a significant part of the puzzle.

So, could China have undergone an Industrial Revolution? No one truly knows, and certainly not I. But to venture a guess: Had the Mongols not conquered the Song, and had several policy choices been made differently, it seems that yes, industrialization could have occurred in China at some point — maybe not around 1200 but well before the 1700s. But it was unlikely to happen, so it didn’t.

We don’t truly know how many possible paths there are towards industrialization. Our sample size is n=1: Great Britain. The rest of the world industrialized by copying the British. So we don’t know which factors were critical and which were just random. My intuition is that there are many possible paths, but each requires a specific, unlikely configuration of social and economic factors.

Great Britain was lucky to stumble upon one of these configurations. Medieval China, just like Mughal Bengal, didn’t have such luck. In fact, it was still relatively far, probably, from putting the puzzle pieces perfectly together. But in theory, it could have happened!

Sources on population: Banister 1992, r/AskHistorians, Population history of China on Wikipedia.

Xue 2005, on the Tang-Song transition seems relevant, but it’s in Chinese and the automatic translation is a bit too confusing for me to do more than skimming it. Other relevant sources on tax policy include Liu 2015 and Wikipedia on Taxation in premodern China.

I’m taking this argument from Matt Ridley’s book The Rational Optimist, in which he writes:

When the Tang empire came to an end in 907, and the ‘Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms’ fought each other incessantly, China experienced its most spectacular burst of invention and prosperity yet, which the Song dynasty inherited.

He also mentions decentralization in an interview for a conservative think tank here.

From Francis Bacon’s Novum Organum, Book I.

The full Marx quote goes,

Gunpowder, the compass, and the printing press were the three great inventions which ushered in bourgeois society. Gunpowder blew up the knightly class, the compass discovered the world market and founded the colonies, and the printing press was the instrument of Protestantism and the regeneration of science in general; the most powerful lever for creating the intellectual prerequisites.

It gets repeated a lot on websites that discuss the Four Great Inventions, but finding it in actual Marx sources was tricky. It’s apparently from an obscure text contained in “Marx’s Economic Manuscripts of 1861-63”: Division of Labour and Mechanical Workshop. Tool and Machinery.

I’m not the one calling it stupidiotic; the seller is!

Compare with a Han-era divinatory compass:

Many if not most great inventions start off as toys or curiosities. Who knows what will, one day, serendipitously descend from the Stupidiotic Magnetic Decision-Aider Fortune Teller Pendulum Game?

I ended up summarizing Xue 2005 in an AI to summarize it and it mentions that economic expansion during the Tang and Song eras was due in part to decreased transaction costs, which seems consistent with easier circulation of money.

Wikipedia describes some debate between historians over this figure here, all of which is sourced from books I don’t have, but it’s clear that the Song’s metal production was far higher than the Tang’s.

This discrimination is mentioned on … The Met website and on this encyclopedia, among other places. Also r/AskHistorians. Sorry if my sources are random!

I read about Pomeranz’s claim in Gernes 2001 and in this article from 2003. Also, it was from a 2000 book, so maybe Pomeranz doesn’t believe that anymore.

Also from Gernes 2001, which is a pretty good article on the topic; its title is China: Unfulfilled Promise.

I’m unfortunately drawing this paragraph only from Wikipedia, especially Economy of the Ming dynasty, Economic history of China before 1912, and Taxation in premodern China. They seem well referenced enough, so hopefully they’re correct. One of them has this quote from a history book (The Cambridge History of China):

Ming government allowed those Chinese people who could attain more than mere subsistence to employ their resources mostly for the uses freely chosen by them, for it was a government that, by comparison with others throughout the world then and later, taxed the people at very low levels and left most of the wealth generated by its productive people in the regions where that wealth was produced.

I’m annoyed that all the primary sources are books that I don’t have the time to go get and read.

Gernes 2001 is again my main source on the implications of Confucian and Taoist thought.

Some good discussion on bureaucracy in this Washington Post article from 2016.

I almost forgot to mention Jared Diamond’s hypothesis that geography is responsible for this centralization — because China is one big plain as opposed to a bunch of peninsulas and islands like Europe — and that this had far-reaching consequences on the number of coexisting countries and therefore how innovative the region could be, due to inter-state competition.

They did industrialize.

But:

1. The America's were much farther a way.

2. China's internal complexities made control a legitimate way of dealing with problems.

Thus Europe did not overtake the Chinese until 1750.

Lack of demand seems the most likely difference overall. Song China had a lot of people, but nearly all of them were desperately poor. Those who were not poor demanded highly individualized products, such as richly and uniquely embroidered clothing. Such products are not amenable to industrial production.

In Song China, I claim, there was minimal demand for mass production, the demand that sustained the industrial revolution in England, for small goods such as iron edges for tools, or nails, cutlery, beads, combs, or hand-mirrors; let alone purchased clothing, iron pots, books, glass windows, or more substantial furniture such as beds, tables and chairs.

This is testable in principle, by looking at large numbers of femur lengths of people from both areas in the relevant eras. Femur length tells you height and therefore adequacy of nutrition (and other attributes of the bone also tell you about nutrition and/or disease, and therefore living conditions). Adequate nutrition implies ability to reallocate spending to other things. Inadeqate nutrition implies the absence of demand for anything besides food.

Besides poverty, the European Marriage Pattern is another difference. In northwestern Europe after the middle ages, newlyweds formed their own household upon marriage; everywhere else, the bride typically joined an already existing household headed by the groom's parents (and maybe also containing sibling couples). New households are the drivers of demand: if they can afford it, they'll buy lots of stuff, new if they can.

I claim that the EMP, something expressed throughout the population, is a more important cultural difference than anything elites wrote about such as Confucianism.