This post, I promise, will be interesting. If I play my cards right, it may end up being beautiful, too — beauty is a subset of interestingness. Perhaps I will manage to make it elegant, or cool, or cute, or sexy. Well, we’ll see about sexy.

What is the relationship between all these words?

I’ve given a lot of thoughts on what beauty is and why it exists (e.g. here, here, and also here). My current best summary is: beauty is a natural form of curiosity geared towards what we crave. “What we crave” depends on quite a lot of things: it could be an individual bodily or psychological need, a social craving driven by culture and fashion, a universal human appetite, or even a universal desire that all conscious beings, including aliens and robots, theoretically share, such as “paying attention to new information.”

But within beauty there are many more specific concepts, like cuteness and sexiness. A beautiful person may be sexy, or cute, or neither, or both. What do these words mean? What are the evolutionary reasons for their existence?

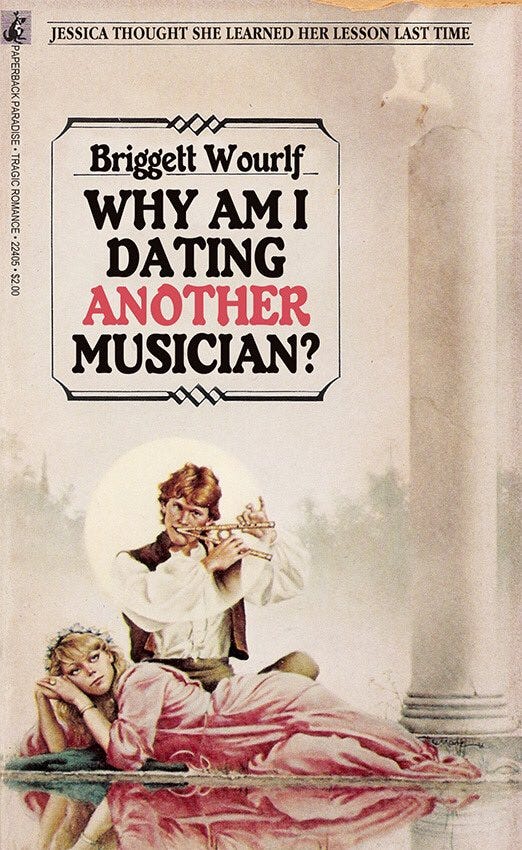

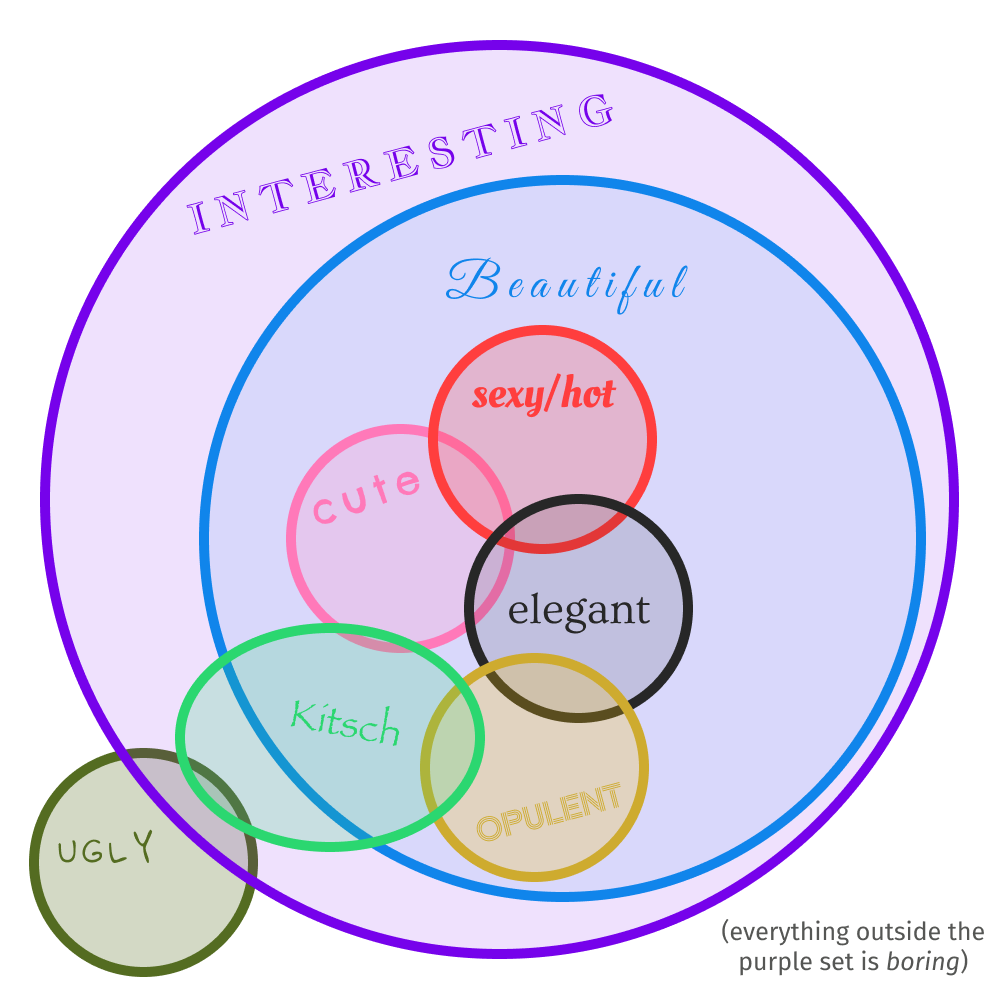

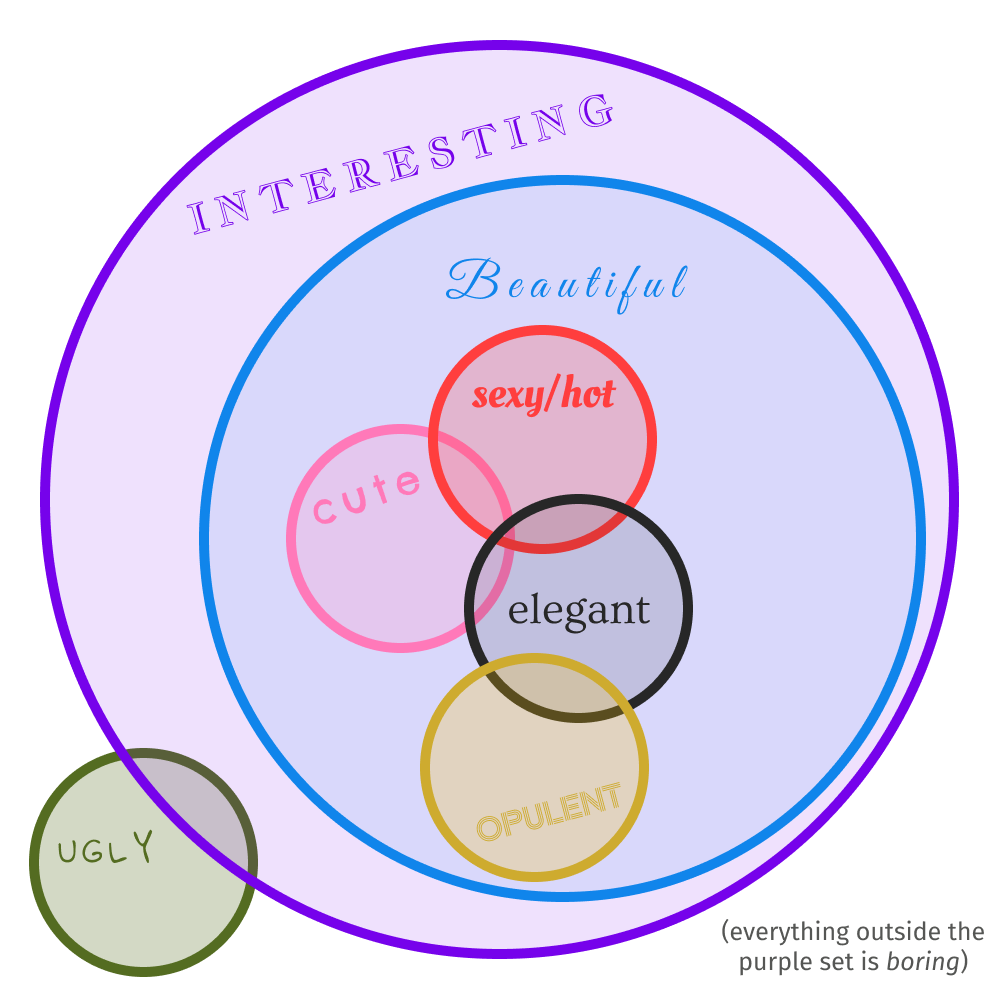

We’ll look at them one by one. Along the way, we’ll try to place them in a Venn diagram, because Venn diagrams are fun.

The basic version of the diagram looks like this:

We already see four terms: interesting, beautiful, ugly, and boring. You’ll notice that I’m claiming everything beautiful is necessarily interesting. This is perhaps not the most standard usage of those words: in everyday language, we may say that something, say a landscape, is beautiful but boring. That’s fine, but if you try to formalize the definitions, as I have done, then you have to recognize that uninteresting things don’t generate much aesthetic pleasure.

In other words, a boring landscape won’t feel beautiful to you. Of course, it may feel beautiful to others, and it may feel beautiful to you in the future. Since beauty is a dynamic phenomenon occurring in the brain, the placement of objects in the Venn diagram depends both on whose perception we’re talking about, and on the moment in that person’s life.

As for ugliness, it is the active opposite of beauty: something that is repulsive, unpleasant. An ugly thing may or may not be interesting. In addition, many things (whether they are interesting or boring) cause neither aesthetic pleasure nor repulsion, and are outside both the beautiful and the ugly circles.

Cuteness

Babies are cute. Baby animals are also cute. Here is a piece of evidence:

Why is this kitten attractive, and why is it attractive in a different way than an adult cat?

Evolutionary speaking, cuteness seems fairly simple to explain. It is the form of beauty that is associated with babies. Babies and children are a pretty crucial part of the continuous existence of human genes, so it’s important that we are attracted to babies as opposed to (for example) wanting to kill them because they are cry so loud. It’s also important that we like babies in a way that is distinct from liking food or sexual partners. Evolution’s solution for this was to create a particular aesthetic sensibility to the features that are characteristic to babies, such a large head and large eyes proportionally to their body.

But why does that apply to kittens? Plausibly, it’s important for cat evolution that adult cats find kittens cute, but we’re interested in what humans think. Natural selection doesn’t care that humans like kittens — or at least, it didn’t care until we domesticated Felis catus.

The reason is that aesthetic sensibility is an imprecise weapon: it transfers easily to things other than the target object. Human babies have large heads, so we learn to love large heads in cats too as in other animals.

But cuteness applies to many other things that don’t have large head relative to their body size. For instance, baby snakes are proportioned similarly to adult snakes:

Is this young snake cute? Probably not if you dislike snakes, but if you do it’s probably due to other attributes it shares with babies: small size, vulnerability, and literally being very young.

Cuteness can apply way more broadly than young animals and people, though:

An elderly person using the internet for the first time can be cute — perhaps because their clumsiness, or eagerness to learn, reminds us of babies.

Toys can be cute because they are associated with children and what children like.

A miniature figuring, even if it represents a fierce warrior or something, may appear cute simply because of its small size.

Just like the more general case of beauty, cuteness is a sensitivity to certain cues that are evolutionarily relevant, but which can be found in a wide range of contexts.

As for our Venn diagram, we can include cuteness as a perfect subset of beauty. Everything that is cute is beautiful, although the reverse is not true.

Hotness, or Sexiness

If cuteness is important to the survival of our offspring, sexiness is important for their existence in the first place. Rather obviously, natural selection depends on reproduction, so it had to give us a way to pay attention to potential mates, especially healthy, strong, competent ones. Thus, hotness.

What makes a person hot or sexy (or seductive, handsome, nubile, arousing, bewitching, or other synonyms)? This question has been studied extensively, and certain physical qualities seem common: facial symmetry, lack of disease or deformity, strong muscles (at least in men), and clear skin. But hotness depends on more than physical attributes. The ability to follow current fashion in clothing or hairstyles, for instance, is often desirable. Prestige and wealth can make somebody hot. Certain skills are attractive: musicians, for example, are generally considered to be pretty sexy.

Just like cuteness, the fact that sexiness comes from the evolutionary need for reproduction doesn’t mean that it only applies to potential sexual partners. A woman can be sexy to you even if you know that she is infertile. You can find a man sexually attractive even if you are also a man and therefore can’t have children with him.1 You can even be aroused by fictional people or images of people, even though you’re never going to have a kid with a pornographic video.

It’s less common to talk about sexual attraction for decidedly non-human things, but sometimes we hear people describe, say, a car as “sexy.” This is probably just using the word in the different sense of generic beauty, though. Unless, I suppose, the person has a genuine sexual fetish for cars.

An interesting case arises at the intersection of “cute” and “hot.” Despite its usual absolutely non-sexual association with babies, “cute” is also commonly used to describe sexually attractive people, as in “a cute guy” or “a cute girl.” Does it have a different meaning than hotness? Well, maybe:

It seems to me that a masculine, muscled, bearded, mature man would be less likely to be described as cute than a young, hairless, thin, and perhaps more androgynous man. That just seems to be because of the connotations of youth. But I feel that this may not be the whole picture, and also the precise meaning of these terms is probably a matter of much debate.

Elegance

What does it mean to say that a design is “elegant”? What about an elegant outfit? An elegant mathematical proof?

Elegance is a common concept in abstract fields like math and philosophy. This suggests that it is very different from the reproductive urges that cause cuteness and hotness. Elegance has very little to do with making babies; and babies are rarely described as elegant, unless they are made to wear elegant clothes.

To a first approximation, elegance seems to be the beauty of simplicity, but that would be (pun intended) an oversimplification. For example, the Wikipedia page on mathematical beauty suggests that a proof can be described as elegant if it satisfies some of the following:

A proof that uses a minimum of additional assumptions or previous results.

A proof that is unusually succinct.

A proof that derives a result in a surprising way (e.g., from an apparently unrelated theorem or a collection of theorems).

A proof that is based on new and original insights.

A method of proof that can be easily generalized to solve a family of similar problems.

We notice several qualities: simplicity, yes, but also succinctness, novelty, originality, and usefulness. Similarly, an elegant design (in, say, a user interface for a web application) is one that accomplishes the stated goal well, without clutter, and in a way that isn’t flatly copied from existing design. In fashion, elegance means clothing that is comfortable but also visually striking, somewhat unusual, and “smart.” Elegance requires conscious thought.

What would be the evolutionary reasoning for the existence of elegance? It probably ultimately stems from our need for order. We tend to desire things that make sense, that are easy to understand, but that also accomplish something useful. There is no direct link to natural selection here: it’s simply using the tools given to us by biology to understand our environment by noticing patterns and desirability.

Can something be cute and elegant? Sure: a child, smartly dressed. Someone may be sexually attractive in part due to their elegance. We can also describe an animal as elegant, for instance swans. In the Venn diagram, we get:

Opulence

Somewhat related — but not identical — to elegance, opulence is the beauty that comes from material wealth.

Wealth can be many things, but in general terms it means whatever people want. It can be measured in dollars or other currency, so it is frequently confused with “having money,” but it is in fact a broader notion: wealth also comprises having more than enough food, security, and all the other basic needs, which means it is useful to survival. As a result, evolution made us sensitive to visible signs of wealth.

Opulence, also called luxury, richness, lavishness, etc., is the resulting aesthetic feeling. It is why this stereotypical luxurious gold chandelier seems pretty:

Opulence overlaps with elegance, but not really with cuteness or sexiness. I mean, it can — it’s not an opposite of them or anything — but it seems pretty rare, and my diagram will get too complex if I try to represent each possible overlap. So:

Kitsch

This is a weird one. Kitsch, and the related concepts of gaudiness or camp, are kind of an ironic beauty — beauty that isn’t supposed to be beauty. Kitsch is the absence of taste. It is exaggeration. It is excess. It is dogs playing poker:

Kitsch would be wholly outside the circle of beauty and squarely in the circle of ugliness — except that the irony is real, and you can actually feel aesthetic pleasure from kitsch. There is also a common overlap with cuteness (cute animals are a staple of kitsch) and with opulence (think of Donald Trump’s golden penthouse). I would argue that kitsch is in some way an antonym of elegance: the two can’t really overlap at all.

But it seems clear that we need to add an inelegant (!) ellipse to our Venn diagram so that kitsch can reach beyond beauty. I would however say that however you cut it, kitsch always manages to be interesting.

Is there any evolutionary reason for the beauty of kitsch? Probably not. It’s more likely just a side effect of the other kinds, driven by basic desirable properties like novelty or color. It is also a result of the ever-moving cycle of fashion: when something previously popular isn’t in anymore, it runs a high risk of becoming kitsch.

Coolness

The last aesthetic concept I want to cover is coolness. What is coolness?

You might expect that cool would be the opposite of hot, but no. Temperature metaphors don’t matter here: a hot person can be (and quite often is) cool, and vice-versa. Elegance and cool also often go hand-in-hand. The other concepts that we covered, however, not so much.

It’s weird that I’m able to say all of this given how difficult it is to define cool. Wikipedia itself sort of gives up and says,

There is no single concept of cool. One consistent aspect however, is that cool is widely seen as desirable.

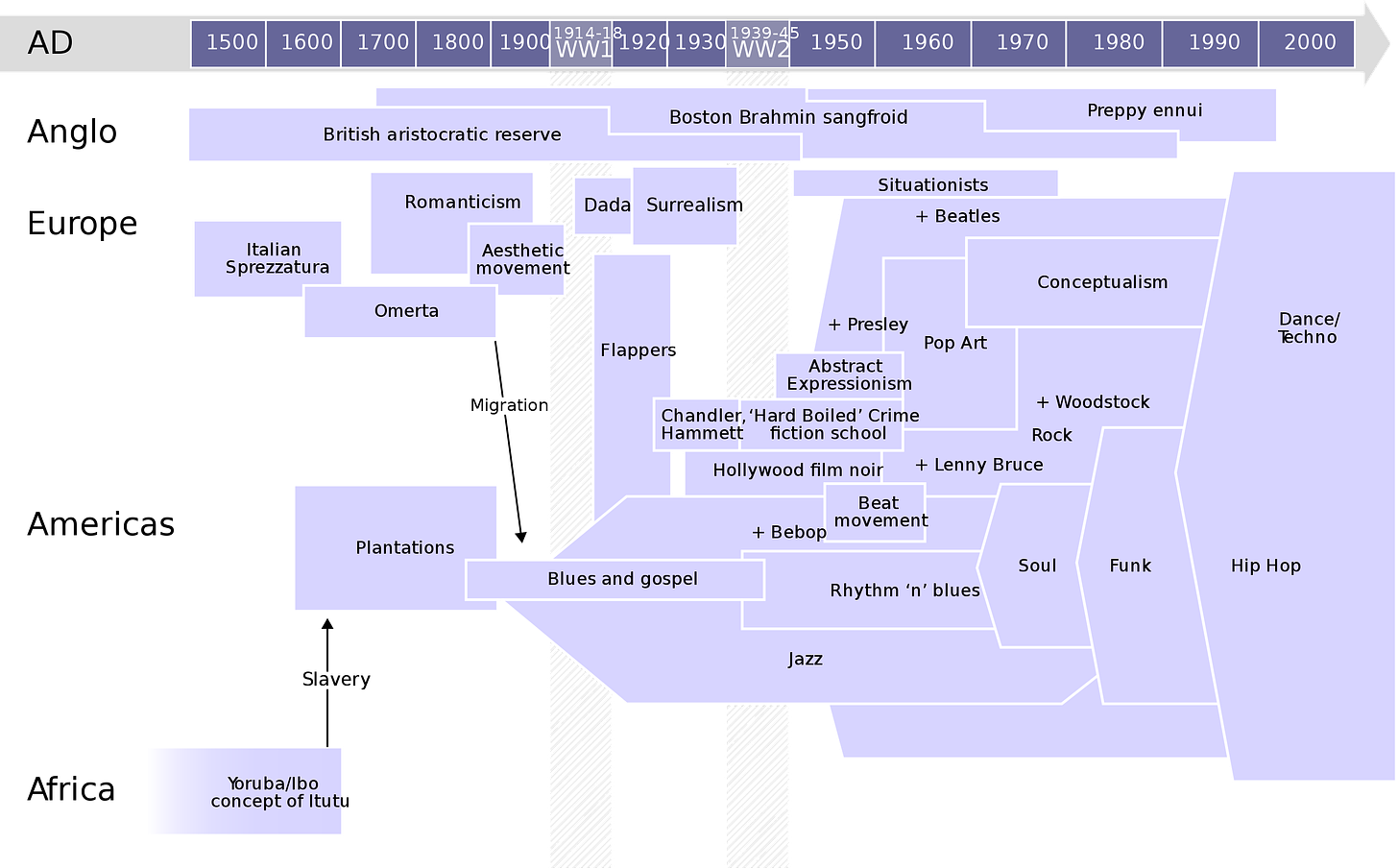

It then provides this helpful diagram of cool throughout the ages:

Cool is associated with certain qualities (at least it is now): self-control, confidence, ironic detachment, or calmness. It is also very commonly associated with music: most of the items in the timeline above are music genres or musicians.

Cool can also be applied to things other than people, although it’s unclear how to distinguish “this is a cool gadget” from just a generic appreciation for the gadget.

We probably feel an aesthetic attraction to coolness not because of natural selection directly, but because of cultural evolution. Humans are social animals that must learn from other humans, and we use something called prestige to determine who we should learn with. The concept of coolness appears to stem from a specific form of prestige, distinct from others such as wealth or hierarchical status.

I think it makes sense to say that coolness isn’t necessarily beautiful, but that it is always pretty interesting. Hence we get to the final version of my Venn diagram, with yet another ellipse because I didn’t plan the placement of the circles ahead:

I could keep going. There are other aesthetic concepts, including: sublime, funny, pretty (a weaker synonym for beauty), erotic, harmonious, appetizing (for food), and many others. Beauty has a vast wealth of synonyms and quasi-synonyms, and it would be a fool’s errand to try to formally define them all.

My Venn diagram is also a fool’s errand: I can easily think of a dozen problems with it. It’s not exactly elegant or sexy. But it was a cool exercise, and assigning colors and fonts to each concept is a pretty cute thing to do. Hopefully the result will also have been interesting to you, and not too ugly or boring.

Homosexuality is still an evolutionary puzzle. It’s unclear why it was never selected against to the point of disappearance. But the answer has to be somehow related to the idea that aesthetics are transferrable.