Look, I know I’m being as contrarian as humanly possible here. Everybody, everywhere, is against food waste. The United Nations is against food waste. The US government is against food waste. The Canadian government is against food waste. So is some sort of cooperation effort between the US, Canada and Mexico. So is the EU. Foundations like the WWF are against food waste. All journalists and public commentators are against food waste. Cooking TV shows are against food waste. Random people on social media, time and time again, unite their voices in a lament whenever some particular media piece on food waste comes out.

I can understand why. It always seems absurd that we spend so much time, energy, and money on growing, distributing, and cooking food, only for a large fraction1 of it to end up in the dumpster. More than that, we all have an instinctive emotional reaction to throwing out food. It’s sad to see the fruit of people’s labor, something that was meant to be enjoyed and life-sustaining, and something that we paid for, serving no purpose because of bad planning or cooking skills. We readily imagine ideal alternative scenarios, ones where we did prepare the food in time, or where we were able to, at least, send it to some poor person who is going hungry somewhere else in the world.

Use a bit of math, and you can even make it seem like a hugely impactful issue. The total value of wasted food across the world has been estimated in the hundreds of billions; if all that food could somehow be given to the people in need, it would feed 1.26 billion people and essentially solve hunger. We wouldn’t even have to produce more!

And look, I’m no different. I also dislike food waste. I feel that tinge of sadness every time I throw away some withered citrus fruit from the bottom of the fridge drawer, or cheese that has become moldy (in the wrong way). I have a strong aversion to not finishing my plate, whether its contents were cooked by myself or ordered in a restaurant, whether I actually like the food or not; in fact my hunger tends to exactly match the quantity of food in front of me, a tendency ingrained since childhood. And if I had a magic wand, I, too, would teleport my unwanted food to starving African kids or something.

So I want to be clear: I’m not arguing in favor of food waste. I’m arguing against being against it. Not because food waste is good, which it isn’t; but because it just isn’t bad enough to care very much about. And yet people do care about it, way too much, and it seems worth pushing back against this view a little, so that perhaps they might turn their attention to more important stuff instead.

To be precise, I don’t mind if you, as an individual, care about your own food waste. I assume you feel the tinge of sadness too, and it’s fine to want to minimize that. More to the point, food waste costs you money, and it’s in your interest to make a good use of your money. No, what I am arguing against is caring about the food waste of others.2 I am against seeing food waste, especially at the consumer level, as a political problem.

The main reason is that it’s unlikely for other people to be more competent than you at estimating the importance of your own food waste. I sometimes see stats such as, “on average, Canadian households could save $1,766 per year if they didn’t waste food.”3 Great, maybe telling this to people might get them to realize some things about life and change their behavior. But assuming that they’re reasonably careful about their money in the first place — which, considering how much people freak out whenever the price of groceries increases by 2% or whatever, seems like a safe assumption — one could make the case that people are choosing to “pay” that $1,766 loss instead of putting effort into avoiding it.

Because avoiding waste does require effort. Managing groceries is already a demanding daily task — what to buy, what to prepare and when — and it’s not necessarily clear that spending more effort on this is the most productive use of your time. And if it is clear, for example because you don’t have a lot of money and therefore need to be extra careful, then you’re probably already doing it. So there isn’t much point in having some government or organization come and tell you you should care more than you already do.

One particular way that reducing food waste isn’t worth it is that often, it occurs as a byproduct of something good: having slack in the supply chain. There’s value in buying a bit more food than strictly necessary, because that makes life easier.

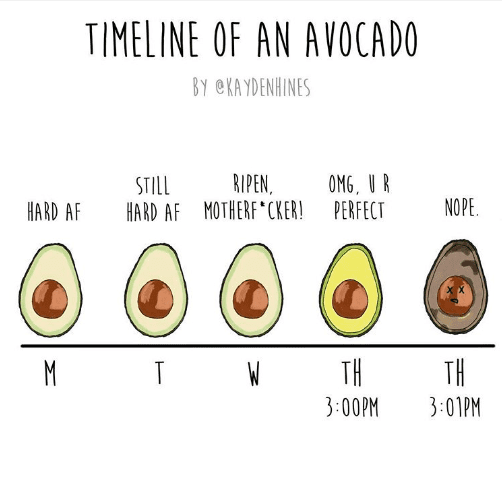

For example, I routinely waste avocados, because I’ll buy a bag of avocados, let them ripen, put them in the fridge, and then use them when the need arises, which isn’t known in advance. I don’t always eat all of them in time, so some of them become brown, fibrous, and generally gross. Could I avoid this? Sure: I could carefully plan ahead all occurrences of needing avocados, and forever renounce the possibility of making guacamole on a whim. That would, of course, be a worse way to live my life. I’m totally willing to waste an occasional few dollars on gross avocados in order to have ripe avocados on hand most of the time.

All of this obviously applies not only to homes, but also to grocery stores, restaurants, and other food-based services. In fact these organizations probably have even stronger incentives to optimize their inventory and avoid losses than you and I do, given that it is central to their business. So if a baker decides that wasting 30% of his production is worth it, because it ensures he has enough bread for all customers in case of a busy day, that’s his call. He has decided that having slack in the chain is more valuable than avoiding waste, and it isn’t up to some UN agency to tell him he’s wrong.

Ultimately, most food waste problems are food distribution problems. We would want, ideally, that exactly the right amount of food be distributed to everyone according to their needs and wants. But that’s really hard. There are always losses along the way, and it’s often worth allowing some excesses in order to avoid lack, and anyway the market can figure it out way better than any government could. In fact, I have a strong feeling that distribution is, in general, underrated as an explanation for how things are. Lots of people don’t realize how important and difficult it is, and that explains much of our world’s obsession with things like food waste.

Look, I understand that, having read the above, you’re probably still very much against food waste (unless you were already a pro-market libertarian who thinks food waste doesn’t even exist, obviously). That’s fine. A full takedown of the anti-food waste-position would require more effort than I’m willing to expend today; after all, I don’t care that much about the topic :)

But I did want to write this post because it represents an excellent case study of a broader phenomenon. Three broader phenomena, in fact:

Mistakenly trying to apply a top-down solution to a problem that arises as a consequence of billions of individual choices, and is better dealt with at that level

Focusing too much on a problem with bad aesthetics

Failing to see that a problem is in fact a symptom of a system that works well

The first of these should be pretty clear after our discussion on individual incentives. Food waste is not, in fact, a “global issue” in which “billions of dollars worth of food” could be redirected to “help 1.26 billion hungry people.” It looks like that only through the abstract of statistics aggregation. Which can be a useful tool, sometimes, for instance in the case of collective action problems where no one has an incentive to act unless others do. But food waste isn’t a collective action problem: the incentives are already quite clear and well-aligned with what people want.

The second is related to the point on emotional reactions to waste, to which we can add the disgust associated with food that has gone bad. Our aesthetic instincts tell us, “this is an important problem! we should minimize the tinge of sadness and/or our exposure to rotten produce!” But that, in itself, doesn’t mean it’s a good idea to devote our time and attention to it. The optimal amount of tinges of sadness and exposure to rotten food is not zero.

But the third item is the most interesting. Food waste, though clearly not good in and of itself, can be seen as a symptom of goodness. It occurs when people are wealthy. Think about it: it is the poor who are most careful with food, because they know it’s a big deal if they waste a lot of it. Being able to waste an avocado and not fret about it is a sign that you’re doing pretty well. At the scale of society, it is good news when households start wasting more food: it means that there’s a lot of slack in the supply chain, and fewer and fewer people need to worry about running out of calories.

This point doesn’t mean that we should try to waste more food, of course. It’s still a good idea, in principle, to waste less. You can save $4 a day or whatever. But it does suggest that we should perhaps not worry too much about it, and rejoice when people are rich enough to afford household waste and lossy supply chains. And once we realize that, we can work on making that true for everyone on Earth, through the much more wholesome action of producing more food, rather than reading UN reports full of pictures of rotten fruit.

I would have liked this to be a precise percentage, instead of the vague phrase “a large fraction.” But it turns that figuring out a single number is tricky. For one thing, food can be lost or wasted at various stages in the chain: agricultural production, processing, distribution, retail, preparation, and consumption. Any number you see can apply to a subset of these. And it varies by country. Also, I don’t know much about this but I assume there can be big divergences just based on measurement and estimation methods.

Just looking at a sample of the many tabs currently open in my browser, I get:

About one third of the world’s food; 931 million tonnes of food waste (about 121 kg per capita)

I think that across the world, “a third” seems like a reasonable approximation. It’s probably higher than that in rich countries and lower in poor countries, although it’s clear that food waste occurs at all levels of development.

One thing it’s definitely wrong to care about is the food waste of the patrons around you in a restaurant. A friend (who will enjoyed being once again mentioned here) told me of a woman who would ask strangers who weren’t finishing their plates to give her the leftovers. This seems to be borderline psychopath behavior.

In Poland, where I live, most people were taught by parents and priests that wasting food is a sin. Mothers and grandmother's typically insist that children eat all food on their plate. On the other hand, when hosting guests it is important to provide more food than they could possibly eat. All of this usually leads to overeating, wasting food or both.

What I figured out some time ago is that given a choice between wasting food and overeating, both are consodered morally bad, but by overeating I am hurting myself, while wasting food doesn't hurt anyone.

I also hate it when people use numbers to promote a simple solution to a complexe problem.

For exemple, this slightly exagerated Health Prime Minister point of view: There is 9 772 family doctors in our province of 8 604 500 people. So if every physician take 881 patients under their care, we would solve every single problem in Health Care.