Why colonize the Moon, Mars, Venus, Ganymede and Titan and the asteroid belt, and then Alpha Centauri and other star systems beyond?

Common answers include: survival, resources, and coolness. Colonizing other planets and beyond would ensure humanity survives even if catastrophe strikes the Earth (including the inevitable end of the solar system in a few hundred million years). It would allow us to exploit the vast mineral and energetic resources of other celestial bodies. And it would be super cool — a way to fulfill the grand destiny of mankind.

The problem with all of these benefits is that they’re not quite guaranteed to work. Self-sustaining colonies that can “restart” Earth civilization in the event of disaster would be difficult to set up, and would be even more vulnerable to extinction than Earth itself, at least for a long time. Plus, whatever kills humanity on Earth (a rogue AI? a lethal pathogen? a gamma-ray burst?) might be able to reach the colonies too. Resource extraction from space would be ridiculously costly and may never be economically viable compared to extracting the riches of Earth and recycling them over and over. As for coolness, well, that depends on who you ask. Lots of people already think we should direct our efforts to solving the problems here rather than create new problems up there. Even those who are driven enough by the call of the stars, those who would see themselves move to the glorious colonies, might find that their enthusiasm is fading when life turns out to be really hard and full of deprivation, not to mention that most of Earth doesn’t really care about them. It might not feel like fulfilling the grand destiny of anyone.

However! There is one benefit of space colonization that is all but guaranteed to happen, provided that we do colonize the stars and remain reasonably human. It’s guaranteed to happen thanks to physics, which puts a hard limit on communication across vast distances. Yet it is very little discussed, somehow, and perhaps not seen as a benefit by everyone. It is this: the flowering of human civilization into a constellation of diverging cultures, all discovering their own ways to live, becoming as many distinct civilizations as there are habitable worlds.

I was thinking about this after reading Robin Hanson’s recent essay, Beware Cultural Drift: Thoughts on modernity’s monoculture mistake. It’s a great essay, arguing for something readers of this blog will recognize as familiar: that optimizing for what seems like the “best” solution across the board can be detrimental, and that the only fix for this is cultural diversity.

For example, now that instant communication across the globe is possible, the cultures of the world are becoming more and more similar, especially among the wealthy and educated. The world elites speak fewer languages than before; they dress similarly; they adopt the same values; even the places where they stay as they move from city to city look the same. The lower classes are still rather differentiated across countries, but less and less so.

This lessening of cultural diversity may seem good in some respects; for instance, if most educated people know English, coordination is easier. But it sets humanity up for a peril, which Hanson calls cultural drift. Often — always? — cultures change over time in ways that are detrimental to themselves in terms of self-perpetuation. When the drifting culture is small, it just slips into irrelevance or extinction, and is replaced by another with better values. This is natural selection, the same force that causes biological organisms to evolve (genetic drift makes individuals and species less fit, but they’re replaced by those lucky enough to have beneficial mutations) or businesses to innovate (old companies with bad corporate norms lose out to new startups with productive cultures).

But when a culture is large and powerful, as today’s global civilization is, there is no selective pressure anymore. And so drift happens, until the culture has become legitimately bad, at least at keeping itself existing, and maybe in other ways too. Hanson gives the example of low fertility, which definitely seems to be spreading all over the current global civilization in a way that threatens the current global civilization over the long term.1

Hanson is pessimistic that there’s an easy fix for “modernity’s monoculture mistake,” but he briefly mentions this:

Eventually, when our descendants spread across the stars, long communication delays will ensure cultural fragmentation, and thus more selection.

The idea seems woefully underexplored. Hanson only mentions it offhand; the Wikipedia page on space colonization, which has extensive discussion of arguments around survival, resources, etc., doesn’t even broach the topic of cultural diversity. I tried looking for academic papers and barely found anything, except an article by a Japanese astrophysicist titled, “Do we disturb the universe?: Diversity in space as a grotesque hope for humankind,” which I found of rather poor quality. (The accusation of “grotesque” in particular seems quite gratuitous.)

Even the space opera subgenre of science fiction rarely deals deeply with cultural diversity at the scale of multiple star systems. Sure, each planet in Star Wars or Dune or Star Trek or Foundation has its own culture, but the differences are usually superficial. This is probably because, for plot reasons, there are always fictional devices that allow instant communication and travel between the star systems. Hard to write an engaging story across the galaxy when every message takes 10-100 years to be answered.2

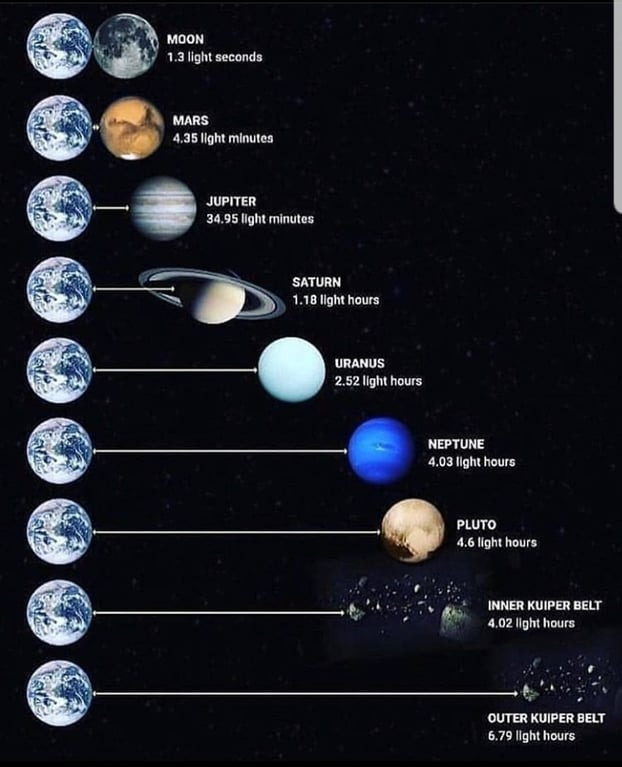

Unless some unforeseen and exotic discovery in physics allows us to create such a device, bypassing the speed of light and making my entire essay moot, communication delays are always going to be a concern for a spacefaring species. Between the Moon and Earth, it takes 1.28 seconds for a message to be transmitted over the average distance of 384,400 km. This seems sufficiently small for communication to be basically unimpeded, if we’re willing to accept a 2-3 second latency on video calls, so the Moon will likely remain part of the Earth’s monoculture.

With Mars, however, the delay is 5 to 20 minutes, depending on the relative positions of our planets. Multiply by two for going back-and-forth, and this clearly means no calls or any kind of synchronous information sharing. It will also likely take weeks or months to travel between the two worlds.

This seems rather analogous to the state of the world roughly between 1850 and 1920, before commercial air travel but after long-distance telegraphy. At the time, you could transmit messages relatively quickly between Europe and the Americas, thanks to the transatlantic telegraphic cable, and travel between them in a matter of weeks, thanks to ocean liners. Thus Europe and the Americas were far from isolated, but I’d say they were isolated just enough to be culturally diverging. The US and Canada were, I think, less similar to Britain and France in 1920 than they were in 1850. Likewise for the republics of Latin America compared to Portugal and Spain.

Go further in the solar system and the delays get longer, although not by more than an order of magnitude or two. With Titan, the main satellite of Saturn, communication would take an average of 1.5 hours, and travel about 10 months, at best. So if the entire solar system were colonized, what we’d see would still be a unique solar system civilization, but with many local “countries” that have their own customs, dialects, political systems, and art, just like we still have on Earth today. It would be protected from turning into a monoculture, but it wouldn’t be extremely diverse either.

If we ever reach other star systems, however, we shift into a totally different mode. The closest star, Alpha Centauri, is 4.3 light-years away, which means communication delays of 4.3 years each way. Hard to make a video call under such circumstances. Travel time, meanwhile, would depend a lot on the type of spacecraft, but would take at best a significant chunk of a normal human lifetime, and at worst a significant chunk of the human species’s lifetime. At the speed of the Discovery space shuttle, it would take 148,000 years. With speculative solar sail designs, we might be able to reach 1/5 of the speed of light, and cut travel time down to 22 years. And this is for the closest star; everything else in the galaxy would take longer.

There isn’t a perfect historical analogy for this, but maybe long-distance travelers in the Middle Ages and antiquity provide an imperfect one. Marco Polo’s trip from Venice to China and back took 24 years, from 1271 and 1295. (To be fair, the travel part was only a couple years each way; he spent 17 of those years in China in diplomatic service to Emperor Kublai Khan. But maybe that’s a risk of the job — you never know if an emperor on the other side of the world will like you so much he won’t allow you to leave. In any case, the Venetians didn’t hear what he had to say about China until he came back.) Earlier still, there were indirect relations between Ancient Rome and Han Dynasty China — information could travel between them, but only painfully slowly. It barely needs mention that Europe and East Asia were, during all this time, extremely culturally distinct.

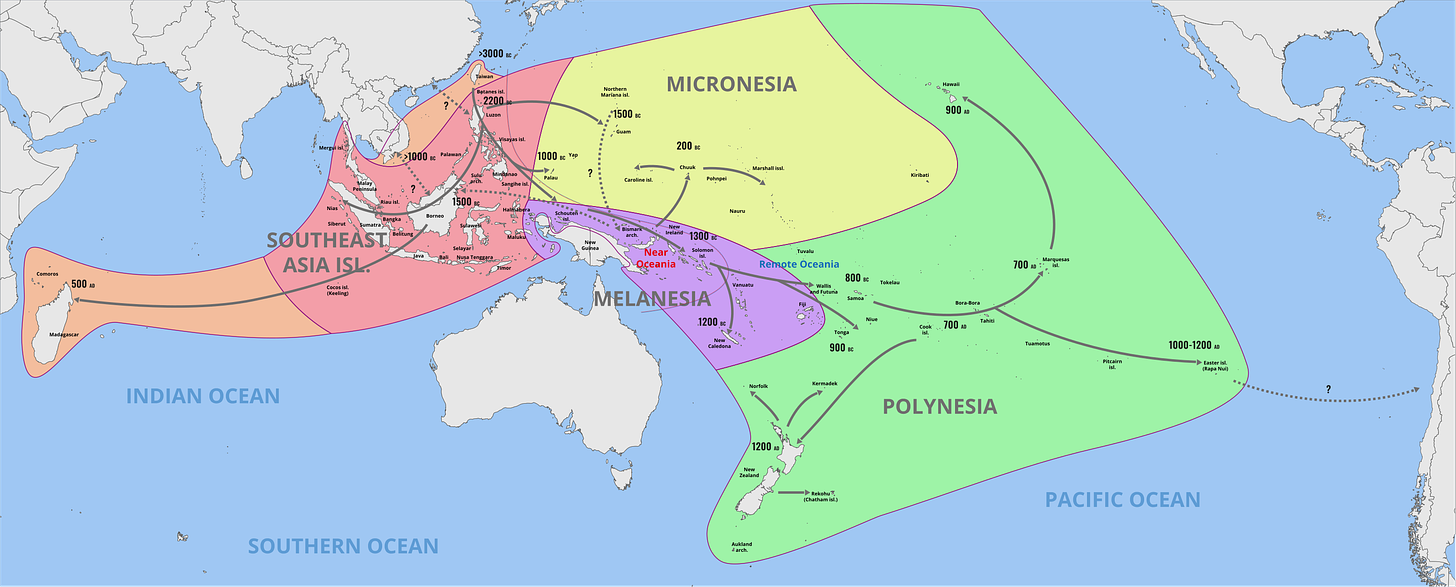

A closer analogy to the colonization of isolated pockets of habitable land, isolated by vast swathes of emptiness, is to be found in the Pacific, where the Polynesian peoples slowly settled everything from Tonga to New Zealand to Hawaii to Easter Island over the course of 2,000 years. It seems that many of these lived relatively on their own after the initial settlement. I believe I recall from reading Jared Diamond on Easter Island that the Kingdom of Rapa Nui was basically cut off from the other Polynesians for centuries. This certainly helped them to develop a unique culture, able to erect impressive statues and maybe even develop writing, although their isolation and small size eventually led to their collapse and conquest at the hands of European explorers.

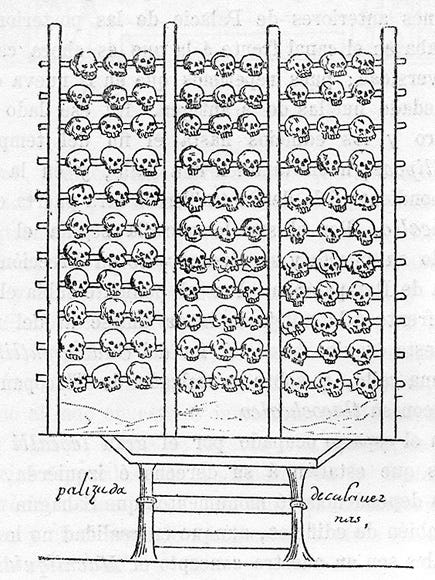

But scratch that: The best analogy, and the greatest episode of cultural diversification due to isolation that we have, occurred further in the past, when humans entered the Strait of Bering and colonized the American continent. For thousands of years there was almost3 no contact between what we termed the Old World and the New, allowing them to diverge wildly. The meeting of the two worlds at the time of the Columbian Exchange — for a dramatic example, the Spanish and the Aztecs — is the closest comparison we can make to a meeting between two alien species. Of course, it wasn’t aliens: just humans who had had enough time to come up with totally different ways to build a society.

This would certainly happen if we founded a new civilization somewhere where could only send or receive news with a 10- or a 100-year delay. Even if both sides of the colonization attempt tried hard at keeping cultural norms the same, there just wouldn’t be enough contact to counteract the random walk of cultural divergence. And then a traveler from one world to the other would find, upon arriving, that the local culture has become totally foreign to him. Perhaps even at the level of its fundamental values; perhaps even in horrifying ways.

Is cultural diversity inherently good? Was it a good thing that Europe and China diverged, that the Polynesian islands did, that the Americas evolved in isolation from Afro-Eurasia?

It’s not hard to see the case for no: just consider human sacrifice in Aztec society. Whenever the topic of the Spanish conquest of Mexico comes up on social media, there are commenters claiming that it was good that Europeans stopped such barbaric practices. The conquest made Mexico more similar to Spain, reducing diversity, but from the point of view of 16th-century Spain, and of those social media commenters, that was a good thing because bad values (the cult of Quetzalcoatl, human sacrifice) were replaced by good ones (Christianity, the Inquisition).

If we agree with this view, then the inherent diversifying effect of space colonization might be seen as a bad thing. It’s bad enough that our descendants here on Earth will have horrifying values (to us, anyway) 1000 years from now; no need to spread to the stars and thereby ensure that some of their cousins somewhere in the galaxy will consider rape or cannibalism or genocide to be awesome. What if the people on a far-off space colony decide that Adolf Hitler was the greatest man to have ever lived and modify themselves genetically to all look like him? That could be an argument for not colonizing the stars.

But I don’t — I don’t agree with this view. For one thing, I suspect that the bad rap the Aztecs are getting is mostly undeserved. They did have cultural practices I would disapprove of, but for the most part they were similar to us: decent people, trying their best at being ethical, doing philosophy, making art. For another thing, it’s not clear that early modern Spain was any better than them. It did, after all, conquer, subjugate, and enslave civilizations it could have just left alone. And it had the Inquisition.

More generally, it’s very hard to be sure that our values are truly the best. They’re always influenced by the culture surrounding us, and the culture surrounding us is always vulnerable to drift. Cultural diversity provides an insurance against that: another society, around some faraway star, could discover better values, and share them with us, saving us from drift.

This is not theoretical, either. It’s happening today on Earth. Consider the outcomes of the colonization of America by the Europeans: although it did destroy much cultural diversity by annihilating the Aztecs and other native societies that already existed, it then massively increased the diversity within Western civilization by allowing Canada, Mexico, Brazil, etc. to develop into cultural alternatives to Europe. One of these places, the United States, has become the global superpower, edging out the UK, France, and Germany. Clearly a successful culture by any reasonable measure.

Today some view the US as a beacon of innovation in the face of a Europe that seems more interested in introducing new regulations than inventing new things. In the past, the US helped defeat the terrible European cultural drift that took the form of nazism. Thus, by colonizing America, a place that would necessarily diverge culturally from the Old World due to long communication delays when the fastest messaging systems were sailboats, Europe insured itself against future cultural problems — even though Europeans can be, on occasion, horrified by aspects of American culture!

We should do the same. Of course, if, as we explore the cosmos, we find planets inhabited by alien civilizations, let’s leave them in peace and engage in careful trade. Let’s not repeat the mistake of extinguishing the cultural diversity of native America. But anything that isn’t inhabited is fair game. It’s not grotesque; it means allowing us and our descendants to make the universe richer, more interesting, more beautiful. It means allowing more stories to flourish. It means a better chance of survival, by combating drift. And it means fulfilling the grand destiny of mankind — to become plural, deeply culturally diverse, and wonderfully complex.

You may disagree that low fertility is a bad thing, but let me reiterate that here we’re primarily considering values to be “good” or “bad” according to how much they help their culture perpetuate itself. Low fertility as a cultural idea is by its very nature self-defeating, since over time the cultures that have it will become smaller and less powerful, while the cultures that don’t (e.g. some religious minorities) will grow.

There are other reasons to think that a declining population is bad, but I don’t want to make that the focus of this essay. I’ll just mention that Robin Hanson suggests that “[a]bsent huge AI advances, innovation rates will then fall even faster than the population, causing a many-centuries-long innovation pause, and then less liberal governance, perhaps including even the return of slavery.”

Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed is an example of a sci-fi story that deals seriously, albeit tangentially, with communication difficulty across star systems. It takes place on a single planet and its moon, but there is an ambassador from Earth who mentions that travel between the worlds, although possible, is slow and difficult. Later novels in the same universe, which I haven’t read yet, feature instant communication using a fictional “ansible” that eventually gets developed.

There were the Norse in Greenland and Newfoundland, the Inuit in the Arctic, and speculatively — did you notice that dashed line next to Easter Island on the Austronesian expansion map? — the Polynesians in South America.

This makes me think of "The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia" which argues that human beings have long sought new and hostile environments as a way of escaping central authority. In your formulation, the culture itself is the authority one might be trying to escape.

Secondly, this makes me think of "Finite and Infinite Games". Culture and civilization should he infinite games; no faction should ever win completely or permanently. Wolves are supposed to subdue their prey, but it would he a disaster to consume all of them. Likewise, empire creates victors and assimilates cultures into a larger, more capable whole (though the process is about as ugly as watching a deer be devoured) but to assimilate everyone surely spells an end to a game that isn't supposed to end.

Great write up! It’s an inspiring thought to imagine that humanity might have a sanctuary far outside our cultural reach.

Where our precedents do not stand, our grand narratives are ignored, our collective unconscious is separated, and our rituals are rescinded.

I’ve seen so many posts craving freedom from our monoculture. Hoping that we might cast aside our phones, embrace more communal living, shift the goals of our city planning, and so many other hopes.

Though the monoculture acts as a Hobbes-like leviathan. The hopes of a socialized ape have little sway over its towering and totalizing presence. As your essay suggests, we might defeat it by distance instead of destruction.

Out there. Among the stars. We can be free. Not only in the way science fiction authors play with a single tweak on a status quo, but a drift of tectonic proportions. This small existence on Earth may be our Cambrian explosion of culture and in a few short millennia we might hardly recognize ourselves.