Bad Attempts at Simplification Rule Everything Around Me

AWM #62: On models, assumptions, data vs. anecdotes, and how Confucius was wrong 📈

This is the Atlas of Wonders and Monsters, where we marvel at the wonders of the world, but also attempt to slay the monsters that lurk. Today we are taking on a formidable foe, one that is at the root of many evils, an overlord plotting in the shadows to make everybody miserable: oversimplification.

Simplification is not inherently bad. In fact it’s not even optional. For all its complexity, your brain is far simpler than the universe as a whole, and almost all attempts at understanding anything in the universe — the movement of planets, economic cycles, a tree, your spouse — end up with you making a model that can fit in your brain. We cannot know anything, except very simple truths, without simplifying.

Some people do this professionally. An epidemiologist, for instance, makes mathematical models to explain the dynamics around a virus spreading in a population. The model is made of equations. It makes some assumptions — for example, that people can never be reinfected by the virus after they have recovered — that simplify reality. Maybe reality is such that 1% of the people are susceptible to reinfection, but this does not matter for the model to be useful. You can’t take every little detail like this into account, it would be too complex, so you make simplifying assumptions. Ideally, these assumptions are explicit, understandable, and grounded in some justification.

But far more often, we simplify without being perfectly aware of what we’re doing. This can lead to all sorts of errors.

In relationships: You can never have a full understanding of another person, not even someone you’ve lived with for years. You always have, consciously or not, a simplified image of the person in your mind. If that simplified image is inaccurate, then you risk harming your relationship whenever you say or do something to them.

The solution for this is called “empathy” or “putting yourself in their shoes.” This means both getting a more accurate model of the person and being aware that you will make mistakes in trying to understand them. Empathy is not easy.

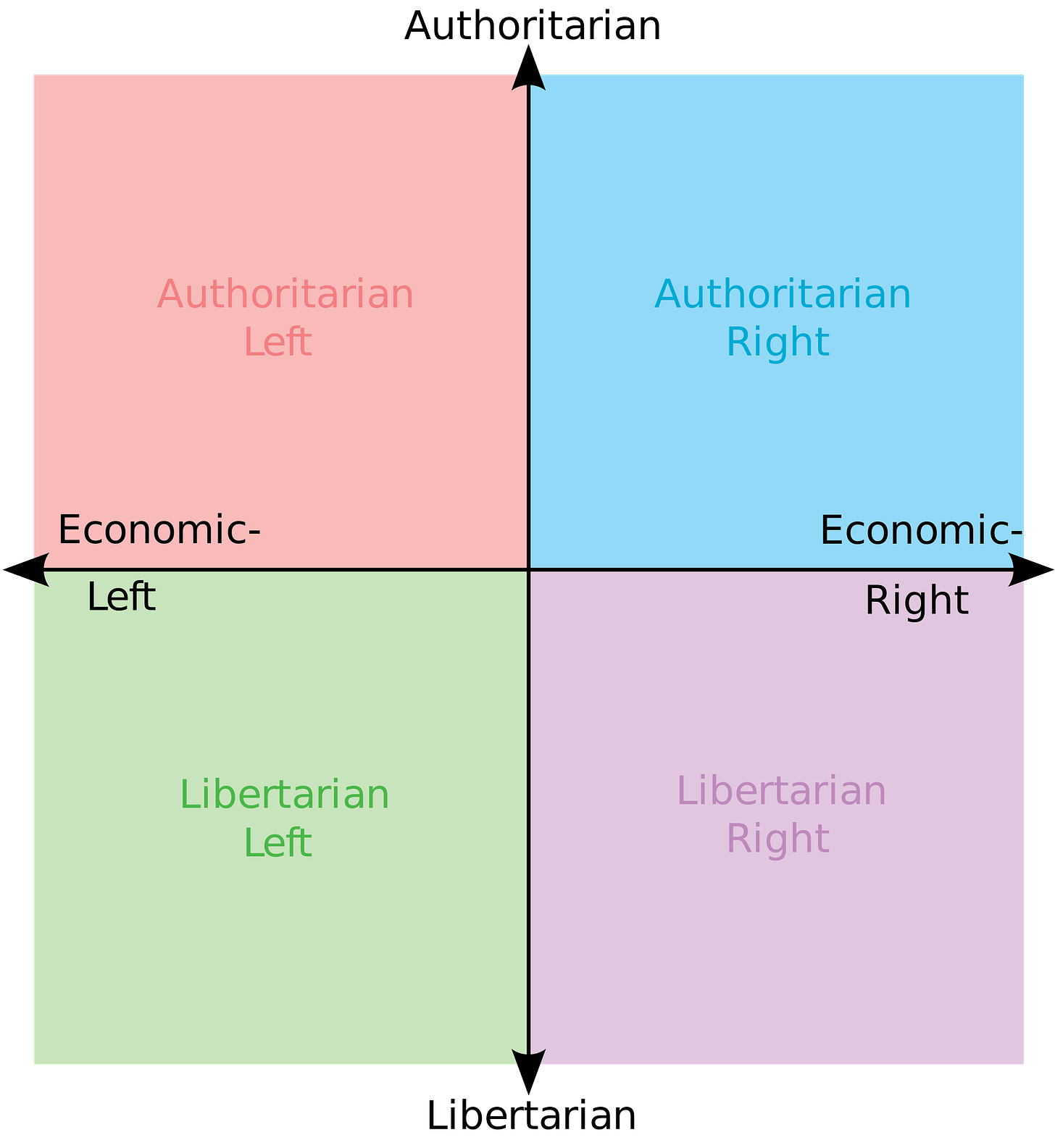

In politics: The collective needs of a society are wildly diverse and multidimensional. Yet in most cases this is reduced to a binary choice, usually “left” or “right.” This is an extreme simplification of politics into a single dimension, and it leaves much to be desired. Sometimes people use a political compass to restore a second dimension, but it’s still woefully oversimplified. Not that we have much of a choice, of course — but it leads to a lot of very… inadequate political discussion.

In policy: Relatedly, when the leaders of a government (or indeed any organization) decide something, they do so with a simplified image of society. This can lead to blanket measures that are easy to think of, and easy to enforce, but turn out to cause harm to a lot of people with special situations that hadn’t been considered. A lot of covid-related decisions in the past two years were like that, like when my government imposed a curfew while forgetting to consider homeless people.

This argument is at the heart of the book Seeing Like a State, which argues that modern governments always tend to reduce the complexity of the world into a high modernist, scientific, technocratic vision, and this leads to poor outcomes. It is notably visible…

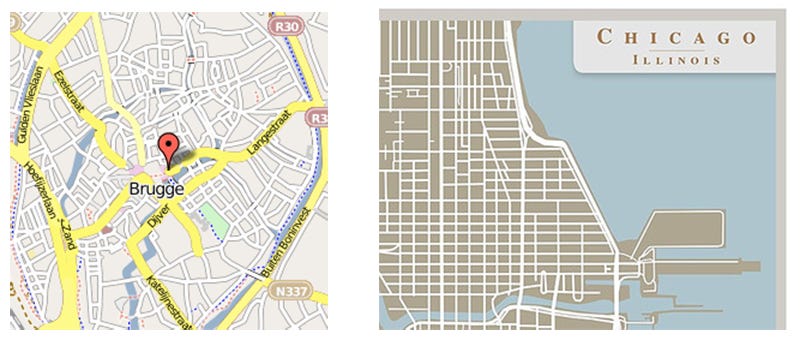

…In architecture and design: Straight lines and basic geometric shapes are far easier to build than complex layouts and ornamentation. They’re also easier to imagine. Make a quick doodle of a house seen from above, right now — and I’m willing to bet it’s a simple rectangle, even though houses often have more complex shapes.

One result of this is that anything planned (e.g. modern cities like Chicago, right) tends to be regular and full of straight lines, unlike the organic complexity that arises naturally when no one is trying to simplify anything (e.g. old medieval cities like Bruges, left). Usually, most people prefer the organic stuff, as evidenced by where people go for tourism.

In science: The Slime Mold Time Mold blog discusses how the discovery of scurvy (which we know today is due to vitamin C deficiency) was not straightforward, because reality is, in fact, very weird. It is the case that certain citrus fruits cure scurvy and others don’t; it is the case that humans and guinea pigs can get scurvy while almost no other mammals can. This is true even though it seems more elegant, simpler, that all citrus fruits work the same way, and that all mammals have the same susceptibility to disease.

Science is the business of understanding reality, which means simplifying reality, which means making a lot of mistakes. The epidemiology model I mentioned earlier is an example of this, actually. It’s too simple for most epidemics! And relying on such models impacts policy decisions in a bad way. The covid pandemic has been a great reminder that reality is far more complex than naïve epidemiology models have suggested, and a lot of bad decisions have been taken by governments who were not aware of such shortcomings.

The Great War Between Data and Anecdotes

One way to illustrate the dangers of oversimplification is what I might call The Great War Between Data and Anecdotes.

One of my inspirations to write this post was this thread, and some of the responses to it, including my own. The topic was Singapore and, in particular, its founding father, Lee Kuan Yew.

Lee Kuan Yew is typically credited with turning Singapore from an inconsequential colonial city into a modern and prosperous city-state. In the thread, Visakan Veerasamy argued that LKY is a complex figure (he’s often described as authoritarian) and that worshipping him, as some do, is bizarre and wrong. Further, he said that the classic story that Singapore was a backwater place before LKY transformed it is a gross oversimplification.

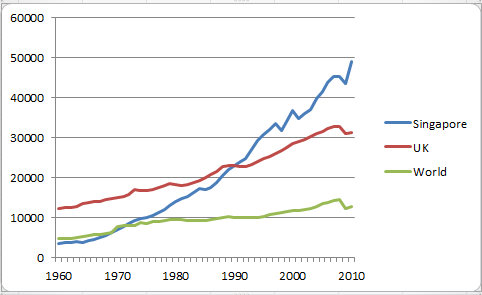

What struck me is that several people responded to this by showing graphs of the GDP of Singapore, like this one:

This data isn’t wrong, and it’s really interesting. But Visakan, who is Singaporean, is having none of the massive simplification the GDP data creates. The apparent prosperity of Singapore, he says, was “paid for in the cost of Singaporeans’ souls.”

“Outsiders,” he says, “don’t appreciate this.” We are in the realm of subjective, lived experience. The people who live in Singapore have a certain experience of living there that can never be fully captured in simplistic data such as a graph of GDP over time.

Data is useful. Data is good. But data is also a massive simplification of a situation. It only takes into account what is measurable, and it assumes that whatever it is was measured accurately. Plus there are many pitfalls in interpreting the data. You can easily form a mistaken image of a country (or a person, or a pandemic, etc.) if you’re not careful.

This is why we need stories. This is why we need anecdotes.

But wait — aren’t anecdotes exactly what you need to avoid when examining an issue? The first tweet I quoted above literally says you shouldn’t only use “anecdotal evidence.” Isn’t that right?

If you’re a journalist and you write at length about the one kid who died from covid in your country, aren’t you obscuring the fact that kids are fine >99.9% of the time?

Indeed. Stories tend to put something into focus at the detriment of many other facets to a situation. They’re a massive simplification. Just like data.

In other words, both data and stories make assumptions:

data simplifies by focussing on what is quantifiable and broad;

stories simplify by focussing on what is narratively coherent and specific.

It would be a pitfall to rely on only one of them at the detriment of the other. If you’re not Singaporean and you make grand statements about Singapore based on whatever is shown at Our World in Data, then you’ll make mistakes. If you’re from there and you rely only on anecdotes from your life and people you know while ignoring whatever is shown at Our World in Data, you’ll make mistakes too.

The Great War Between Data and Anecdotes hides the fact that these two things should, in fact, be allied.

Simplify with Awareness

When making such a broad point as “we make errors when we try to understanding things,” there’s a risk of being so obvious as to be useless.

Is it obvious that simplification is risky? That both data and stories are necessary, that “the map is not the territory,” that “all models are wrong, some are useful”?

I wish. But every day I see mistakes being made that could be avoided if people were just more aware of how they’re simplifying the world. Conflicts that wouldn’t occur if the two parties had more accurate models of each other. Political decisions that wouldn’t be taken if leaders weren’t limited by the low resolution they have of the society they govern.

What is ultimately comes down to is really this: awareness. Simplification in unavoidable, but if you’re aware of what you’re doing — whether it’s adding assumptions to a mathematical model, or saying “I think my husband will react like this but I’m not sure,” or mentioning caveats when using data, or illuminating anecdotes with stories — then it’s all good. It is when we simplify without realizing it that we make mistakes.

When Confucius said that “Life is really simple, but we insist on making it complicated,” he was wrong (or oversimplifying). Life is actually quite complex, but we unwittingly make it simple, to our great sorrow.

A fun thing to notice: Collin has some basic deconstruction on data collection error and problems of bad interpretation. Also some data are just not "collectable" in a sense, and requires some intuition to work around. https://desystemize.substack.com/

"Simplify with Awareness" in essence becomes a paired indicator to not overfit or oversimplify. Imagine if there is a way of achieving this with less difficulty. https://swellandcut.com/2017/09/04/the-five-types-of-paired-indicators/

This was great!

I was reading another Substack last week - link after comment - that discussed how we need chaos to add complexity to stories, that it makes writing/movies/etc. more believable because history and real life are soooo complex and messy. Even in myself, I feel the drive to simplify and minimize - but often it comes from a place of desiring control. That might be an element of our desire to oversimplify people and life and even political motivations - we just want to be able to choose right or left.

Thanks for writing!

https://countercraft.substack.com/p/worldbuilding-and-the-whims-of-history