Bad news is good news, and I don’t mean that in a twisted Orwellian way where “good” is a euphemism for “bad.” Nor do I mean that bad news aren’t bad — they often genuinely are. Instead, I mean that the very existence (and supposed dominance) of bad news over good news is, in itself, a good sign.

My reasoning isn’t very complicated. News, almost by definition, are unusual. Something that happens every day is not news. So when something bad (e.g., a murder) makes it into the newspaper or TV news or whatever people read and watch these days, it’s usually a sign that that thing doesn’t normally happen. If murders were a routine occurrence in a given location, the local media wouldn’t report on them. Hence, news of murder, though bad, are a sign that you live in a place where murders are unusual enough to be news, which is good.

Of course, it isn’t very fun to read about a murder that’s happened in your city. And it is natural to update your understanding of the world in response. Perhaps you never really thought about murders at all, and now you know that occasionally, they do happen near you. This is valuable information, right? And indeed that’s why we read the news: to gain valuable information about the world.

But we know that excess of news can be detrimental to mental health. It can be stressful, depressing, distressing. Someone reading about a murder in their neighborhood might become more fearful, less willing to go take a walk at night, less happy. One could say it’s the cost of seeing the world as it is: there’s bad stuff out there, and it’s useful to know about it, and you’ll just have to deal with the psychological effects somehow.

I prefer the other perspective. The one where we realize that the news is necessarily biased towards the unusual and the interesting, and therefore gives us a twisted picture of the world. The twisted picture is useful and true — but it is not representative of what life feels like on Earth, with all its ordinary parts, good and bad.

That perspective seems to be in direct conflict with another one of my pet beliefs, which is that bad news, contrary to popular thought, is not actually that prevalent in the media.

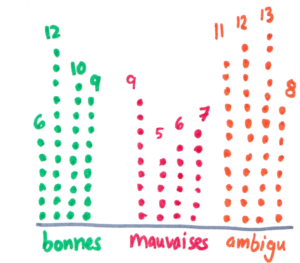

Five years ago, for an old blog post (in French) on this same topic, I went through a bunch of local newspapers and classified each news as good, bad, or “ambiguous/it depends.” Let me show you the output of my data skills at the time, because I’m quite proud of it:

Clearly a candidate for r/DataIsBeautiful. But also, note that the most common type of news is “ambiguous.” The least common is “bad.” This was all very subjective, of course (and we’ll discuss definitions in a moment), but it’s quite clear that unambiguously bad news aren’t dominant.

The coffee shop where I worked yesterday had a paper copy of the same newspaper, so I repeated the exercise, and got 9 ambiguous/neutral news items, 8 bad, and 2 good. That’s a sharp difference in good news, and with a sample size of n=1 it’s hard to say why, but I note that ambiguous news are winning again.

If I had more time and motivation I would use machine learning to classify news as positive and negative over a large dataset, but I don’t. So instead we can look at two papers that were somehow not authored by the same person even though the two main authors have almost identical last names (Ag[g]arwal), they were both at the the University of Duisburg-Essen, both papers are from 2019, and the topic is the same. None of this is relevant but it’s kind of a funny coincidence. Anyway, one paper tried to create a good/bad news classifier, and the other to create a good/bad news classifier. The results of their training is less interesting to me than the data they used. The first paper used a corpus of 300 English news articles, annotated thus:

52 good news

131 bad news

117 neutral news

Looks like bad news were dominant here. But what were their definitions?

Good News: If the subject of the article is someone being saved from danger, the creation of medicine which can cure or help with an illness, the end of a war or some kind of disaster, human rights being defended, or something that benefits the public or a dangerous culprit being arrested.

Neutral News: If the subject of the article is a popularization of science, history or geography, describing humanistic traditions, astronomy, nature, history or landscape, scientific literature, news of people’s livelihood without casualties or daily entertainment and fashion news.

Bad News: If the subject of the article is a war, accidents, disaster, epidemic disease or killing, criminal activities, the death of a famous or important person, some sort of discrimination, bullying or stereotypes, some negative influence or event regarding economics,

Seems reasonable, although not exactly how I would do it. I’d tend to classify science news as good in most cases, and something like “a dangerous culprit being arrested” as potentially ambiguous (which is not the same thing as neutral, but I’d put neutral news in an ambiguous category). It’s good that the person was arrested, but bad that they (presumably) committed a crime. If you didn’t already know about the crime, your takeaway from such a news item might be rather negative indeed.

The other paper doesn’t give numbers, but it did also note that definitions are tricky, especially because:

News can be good for one section of society but bad for other section. For example, win or loss related news are always subjective.

That’s what I had found too. A lot of the news, for example, is political — and almost by definition, political news tends to be interpreted as good or bad in almost equal measures, depending on which side you support.

(As I write this, we’re one day after the American midterm elections, which seems like a record-breaking level of ambiguousness in news reporting. The final results are still up in the air, making everyone, regardless of political affiliation, and including a whole lot of non-Americans like me, unsure of how happy they should be.)

I suspect that we have a bias to see ambiguous or subjective news as negative, even when it isn’t negative in an objective manner. There are a few potential reasons:

Politics is annoying and complex, so most political news seems bad by default, even if it always benefits at least some segment of society. If you hate all parties in your country, then the election of any party will be bad news!

Most news, even good news, also contain some measure of negativity, such as the case of the arrested criminal above, or any news about solving a problem. It’s not fun to be reminded that a problem exists.

We’re just more sensitive to bad news by default, so we notice them more. Also known and widely documented as the negativity bias.

But the main reason, probably, is simply a reformulation of my initial point: our ordinary lives are mostly fine, and this puts a cap on the possibility of objective good news. The best news in my grand-parents’ lifetime was probably the end of World War II — but to create that good news, there had to be 6 years of horrible war. Overall, not a very enticing deal.

In the absence of a major war or crisis, there’s still plenty of good news, but most of it is either subjective or minor. Events such as “local student wins a prestigious scholarship” or “company will open a new factory in your city” pale in comparison with the objective evils of death, destruction, disease, and crime. It’s easier to deviate from the baseline by going under rather than above, because that baseline — ordinary life — is pretty good already.

Bad news may not be that prevalent, but even the feeling that it is is good news.

A few parting thoughts, in no particular order:

There is of course plenty of ordinary evil in the world — stuff that will never make the news, but is still bad. Death from old age doesn’t make the news, but it’s not a reason for rejoicing either.

As a result, there is potential for really great news, without the associated “cost” of newsworthy negativity, if we solve these ordinary evils. And in fact we have been doing just that for a lot of ordinary problems like extreme poverty and child mortality.

If you feel that your mental health is impacted negatively by the news, it’s always worth keeping in mind that you probably don’t really need the news. Most people can do without.

If you do read the news anyway (like I do), always remember the main point above: it creates a view of the world that, while usually true, is deliberately twisted.

And finally — if you truly feel that there should be more good news… Well, go out there and do something that’s both good and newsworthy! The world is just made up of normal people, and the news is not some elite spectacle that you can’t access. Just do stuff! Especially if you can solve the ordinary evils!

I think there are a few additional factors that complicate the picture:

-front-page news is consumed way more than the rest, so the bad/good ratio in the top stories matters a lot. When I did an informal survey of two weeks of NYT front pages, bad was more prevalent than good by like 5:1.

-even if people encounter a mix of good and bad, bad draws more attention (https://assets.csom.umn.edu/assets/71516.pdf). This is true in news consumption as well (https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1908369116)

-the badness of bad stories is much greater than the goodness of good stories. What's the opposite of "child brutally murdered"?

That could add up to a situation where, even if there's an equal amount of bad stories and good stories, the average news reader will come away feeling like things are very bad.

A good rule of thumb on good news vs bad news are from Gottman and Losadas: In general the amount of good news to bad news should be between 2:1 and 10:1, and optimally 5:1. If the positivity exceeds 91% then it is should raise eyebrows on being a Potemkin affair. Since the Lizardman ratio (minimal percentage of contrarians) is 4%, if the positivity rating is higher than 96% then the news can be considered homogeneous.