Book Review: ‘The Sense of Style’

AWM #69: On being a better writer, classic style, and the curse of knowledge 🖋

If you write essays or academic papers in the English language, then you must absolutely read Steven Pinker's 2014 writing guide, The Sense of Style. Realistically, you won't (who has time to read books, anyway?), so at least read this review of it.

Pinker's book can be read as an updated — and partial takedown — of older guides like Strunk and White's The Elements of Style. It does contain plenty of rules and advice, especially in the sixth and last chapter, which provides an overview of many common problems of vocabulary, grammar, and punctuation, with abundant detail. But this part is the least interesting one, especially if you're the kind of person who already pays attention to the rules of language. Most of the value of the book is in the first few chapters, where Pinker discusses two concepts I hadn't seen presented in this way before: classic style and the curse of knowledge.

Classic Style

It's trivial to say that writing can be done in many different styles. It's trickier to name those styles, let alone pick one as the generally superior option. Pinker identifies a good candidate, one that has been around since French writers like René Descartes invented it in the 17th century: classic style.

Writing styles can be described with metaphors of human experience. For instance, “practical style” fits the metaphor of a someone teaching something to a student. One of the two main metaphors for classic style is “a window onto the world.” The goal is to show the reader something true that the writer has noticed but the reader may not have yet. In this metaphor, the writer knows the truth and simply presents it, in clear language, without formally arguing for it. The other metaphor for classic style is a conversation between writer and reader. The two are equals, seeking truth together.

Classic style has several cool properties. One is that it trusts the reader to be a competent adult. This makes the reading experience more enjoyable than being treated as an immature child or an enemy. In fact, when done well, classic style “makes the reader feel like a genius.” You feel understood, smart, appreciated, just like after having a meaningful conversation with somebody you know and trust.

Another property of classic style is that it emphasizes natural human behaviors: seeing (the window metaphor) and talking (the conversation one). By contrast, writing is unnatural: it involves memorizing a bunch of bizarre symbols and learning how to make meaningful strings out of them. Therefore, to ease the weigh on the reader’s shoulder, it’s better to focus on seeing and talking, which are innate. Hence the common advice to show, don’t tell and write like you talk, two hallmarks of classic style.

A third property is requiring the writer to pretend they already know the truth. In classic style, you don’t use the writing process to figure out what you’re trying to say. Of course, it’s perfectly fine to actually figure out what you’re trying to say through writing — you pretend to already know the truth, even though in practice you probably learned it along the way — but then you should strip your final draft of any traces of your thought process. Readers are generally interested in the truth you’re presenting, not your personal story of finding that truth.

Of course, classic style is not the only style around. It is appropriate for essays, blog posts, articles, anything aimed at generic readership; but not necessarily for highly technical writing, instruction manuals, didactic material, or political speeches.

What are the other styles Pinker mentions, and how do they contrast with classic style?

Contemplative or romantic style: Here the goal is to express the writer’s emotional reaction to something. Good for diaries, poetry, songs, some fiction, personal essays, etc. Less concerned with the objective truth than classic style is.

Prophetic, oracular, or oratorical style: The writer attempts to unite their audience with language used as music, and the gift of seeing things that no one else can. Good for political speeches or religious sermons. Assumes a one-to-many relationship as opposed to the one-to-one of classic style.

Practical style: The writer and reader have well-defined roles, usually something along the lines of teacher and student. The writer seeks to transmit information that the reader needs. Good for manuals, schoolwork, research reports, memos, recipes, etc. This contrasts with the equality between reader and writer in classic style.

Plain style: This one is more subtle, and not so different from classic style. Pinker says that plain style puts everything in clear view, with simple language, whereas classic style makes the reader work a bit to get to the truth. I’m not sure I fully grasp the distinction, but I do like this example from the book. Note how the second line makes you think a bit more, and is more ultimately satisfying:

Plain: “The early bird gets the worm.”

Classic: “The early bird gets the worm, but the second mouse gets the cheese.”

Self-conscious, relativistic, ironic, and postmodern styles: This family of styles contrasts with classic style in its emphasis on abstract philosophical questions, like “what is truth?” Such questions tend to hinder the quest to actually present truth. Pinker provides us with some delightful takedowns of stuffy postmodern academic prose that not only makes readers feel stupid, but also manages to say almost nothing about the world. He does mention, though, that everyone is always a bit postmodern; our relationship with truth is complex and full of biases, which we need to be aware of. But in classic style, you have to “artfully conceal [anxieties about truth] for clarity’s sake.” Philosophical questions otherwise just get in the way.

These styles are not clearly delineated, and any piece of writing can involve a mix of them. But practicing classic style — and the various pieces of advice Pinker gives us to do so, like avoiding excessive metadiscourse,1 zombie nouns, clichés, passive voice, and abstract thought — can help us improve all writing, including academic papers. Classic style is an ideal: not something we can always pull off, but something we should generally strive towards.

The Curse of Knowledge

Steven Pinker is first and foremost a cognitive scientist. which is relevant for this section on what is going on in the mind of writers.

The curse of knowledge is “a difficulty in imagining what it is like for someone else not to know something that you know.” This concept, Pinker points out, keeps being rediscovered, and so it goes by many names. Curse of knowledge is a term originally from economics. In various subfields of psychology, the same idea has been called egocentrism, hindsight bias, false consensus, illusion transparency, and mindblindness. I have myself written about similar ideas such as obviousness and awareness and empathy.

Pinker says that the curse of knowledge is “a pervasive drag on the strivings of humanity, on a par with corruption, disease, and entropy.” Nothing less. He also says that it is “the single best explanation I know of why good people write bad prose.”

I agree with both these assessments. The crux, then, is in how to lift the curse.

The first step is to think about the reader. This is not sufficient, because we are bad at empathy and can’t model other people accurately. So our guesses as to what readers know are often wrong: we tend, for example, to think that what is obvious to us is obvious to everyone. But I suspect that so few people actually use this simple trick that it’s worth repeating often. Put yourself in your reader’s shoes. This is the first and most important lesson for a writer.

Pinker’s specific advice to deal with the curse mirrors what I’ve been writing about in my exploration of ideal scientific style. For instance, avoid the excessive use of abbreviations, since “the few seconds they add to [the writers’] lives come at the cost of many minutes stolen from the lives of their readers.” Avoid jargon: murine models is almost always worse than rats and mice. Add short explanations to any technical terms you must use:

A writer who explains technical terms can multiply her readership a thousandfold at the cost of a handful of characters, the literary equivalent of picking up hundred-dollar bills on the sidewalk.

There’s more: use plenty of examples, avoid Latin phrases that have an English equivalent, pick the clearest possible technical terms, use concrete imagery that stimulates the senses (“a quiet room” instead of “conditions of good acoustic isolation”), and so on.

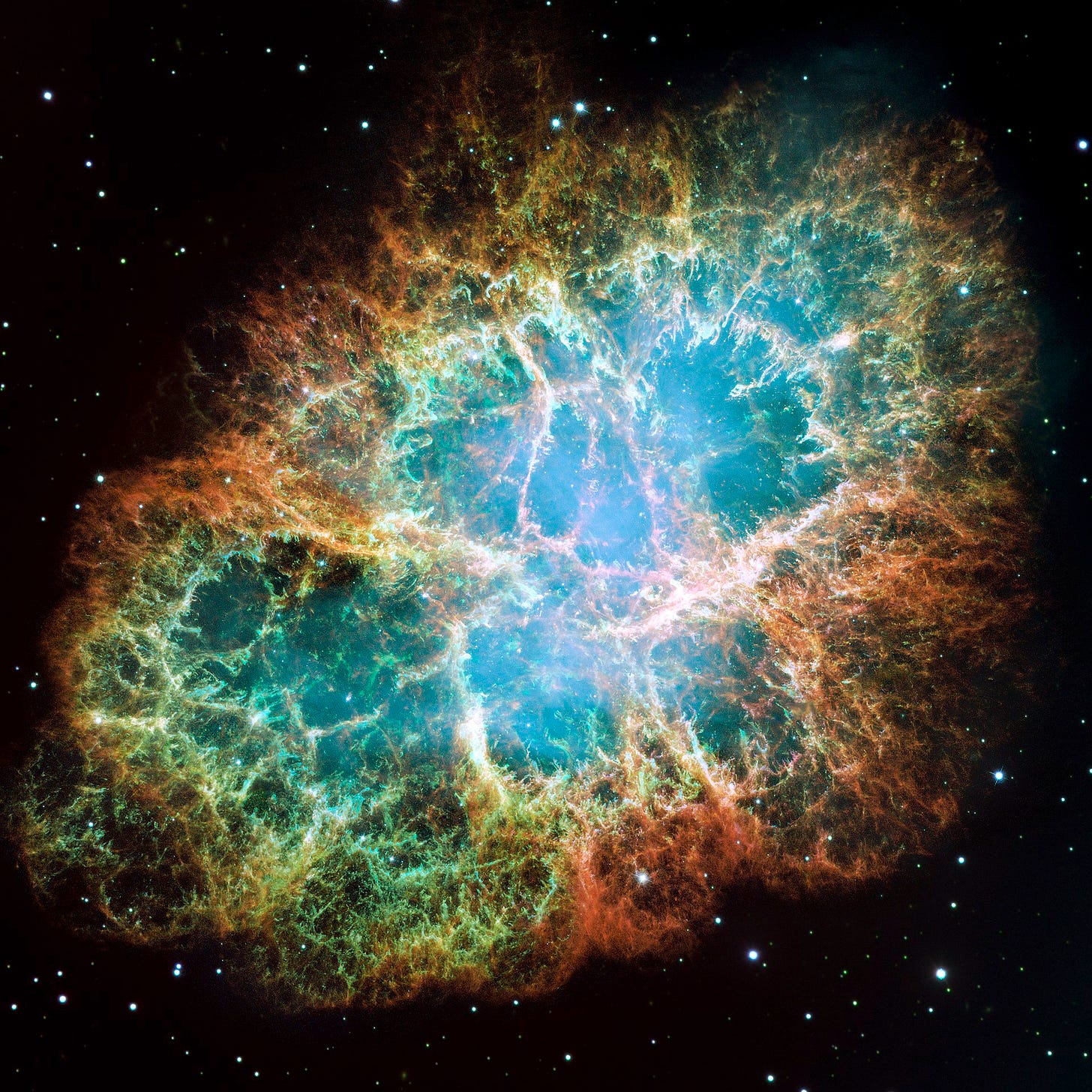

Two concepts from cognitive science support Pinker’s arguments: chunking and functional fixity. Chunking — which has a pleasantly simple and evocative name! — is the phenomenon of repackaging information into units that occupy a single slot in our limited working memory. Remembering a string of digits like 4-7-1-0-5-4 (as, say, a passcode) takes six slots and is difficult, but chunk it into 47-10-54 and now it’s only three slots. Assuming you’re used to dealing with two-digit numbers, it’s way more manageable. Maybe you are a history nerd and even recognize that this is the probable date of the Crab Nebula supernova: July 4th, 1054.2 Nice, now this string of six numbers takes a single slot of your working memory!

Chunking explains one of the ways the curse of knowledge afflicts us: it’s because we don’t all have the same chunks. If I want you to learn my passcode and I tell you “the date of the Crab Nebula supernova,” but you have no idea what a supernova even is, then I have failed to consider what you don’t know. The chunk I use is not one that you have in your mind. And if you don’t care about history or supernovae, it might be difficult for you to properly package it into something useful.

The other concept that makes the curse of knowledge a curse is functional fixity. This means thinking of things in terms of what they do as opposed to what they are. When you write about a topic you know well, you stop seeing the tangible stuff — colors, shapes, sounds, textures. Such concerns become boring compared to what the thing does — which is what you care about when you’re experienced with a topic. Therefore you’ll say “conditions of good acoustic isolation” as opposed to “a quiet room.” But for readers, concrete and sensory wording is better. You have to be mindful of the curse of knowledge for this not to become a hindrance.

Pinker ends this chapter by urging writers to think about how other people think and feel:

It may not make you a better person in all spheres of life, but it will be a source of continuous kindness yo your readers.

Indeed. Be kind. And if you’re writing a scientific paper on a complex topic, then be extra kind.

Other Thoughts

There is much more in The Sense of Style. I haven’t mentioned the middle two chapters, on syntax (the structure of sentences) and coherence (the structure of paragraphs and entire essays). These were less immediately useful and new to me, but they still contain plenty of good advice. I particularly liked his enumeration of the fourteen types of connections that can exist between ideas (with examples of typical connective words):

Similarity (“and”)

Contrast (“but”)

Elaboration (“in other words”)

Exemplification (“for example”)

Generalization (“more generally”)

Exception after a general statement (“on the other hand”)

Exception before a general statement (“nonetheless”)

Sequence: before-and-after (“and then”)

Sequence: after-and-before (“when”)

Result (“so”)

Explanation (“since”)

Violated expectation (“yet”)

Failed prevention (“despite”)

Attribution (“according to”)

Apparently that’s it. Taking into account some inevitable grey areas, these are all the ways that ideas (and therefore sentences and paragraphs) can relate to each other. No need to memorize them, but it’s pretty neat to see them laid out like this.

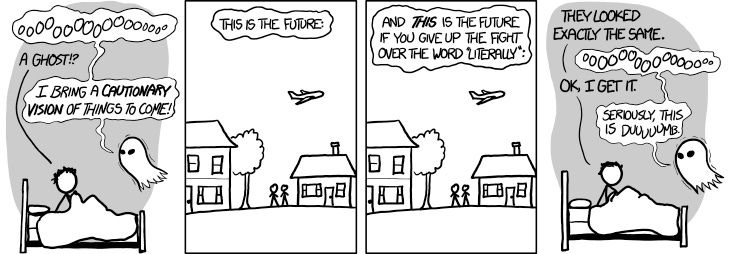

In any case, the book is worth reading in its entirety. It’s a rather pleasant experience, in part because of how Pinker often quotes comic strips to illustrate a point—

—but also because the book is well written (it would have been pretty ironic otherwise) and, importantly, very nuanced. It’s hard to disagree with much in The Sense of Style: Pinker anticipates most objections, and he rarely makes sweeping pronouncements on what is right or wrong. When he does, his pronouncements are backed with persuasive arguments and evidence from psychology.

Whatever you think of Pinker as a public intellectual, he is clearly somebody who cares about good writing. As he puts it, style matters for three reasons: it ensures ideas get communicated effectively, it earns the trust of readers, and it adds beauty to the world. These are three worthy goals.

The one problem I have with The Sense of Style is… well, it’s not a problem in the book, but a problem in what I want to do, namely improving the readability of science papers. Since no part of the book is useless, it can’t really be distilled into something that is quickly digestible. That’s not a big surprise: writing is an art that takes years to master, so of course you can’t learn it all in one tweet or blog post.

The problem is that it’s not reasonable to expect scientists and grad students to get trained as writers. This book, like most books, requires some investment of time as well as interest in improving the craft of writing. Without time or interest, it will be as useless as any other style guide.

Hopefully this book review helps.

This post is part of my project to make science papers more easily readable. Subscribe here for monthly news:

Metadiscourse means discourse about the discourse, such as the words “section” and “discusses” in the sentence “This section discusses two important concepts.”

Maybe 4/7/1054 is not the format you’re used to, but you’re able to deal with that, aren’t you?