Crashing Into Something or Someone, Perhaps Repeatedly and Only for Fun

Risky play as a coordination problem 🤼

When I was in elementary school, in the last couple years of the 20th century, there was a wonderful grove in the schoolyard. As an adult once I went back, and it was tiny and sparse, and I wondered if they had cut down some of the trees. More likely the woods were simply quite small from the beginning, and the illusion of vastness came from being small myself.

The woods were by far the most fun part of the schoolyard. We divided ourselves into rival “camps,” gangs of 6- or 7-year old children who scoured the woods to collect rocks and plastic bags that we accumulated in secret bases hidden in some of the bushes. There we would grind the rocks into powder and collect that precious resource in the plastic bags. What we hoped to achieve by doing this, I do not remember. But it was great fun. There was drama and gossip (who was part of which camp??), there was nature, there was competition, and there was a lot of physical activity.

I can’t remember of anything else I did during recess, other than, in winter, sliding down a small snow hill — another rather risky activity.

But evidently we did do other things, because one day the teachers decided the woods were off-limits. At first they forbid it during winter, I think; they gradually the prohibition extended to the other seasons. We children were appalled. Why were they taking out the most fun part of recess? Why were those adults warring against fun?

I lied — I remember another activity I did, I think around grade 4. I stood near the place where we would line up to go back into the school at the sound of the bell. That way I would be first in line, not that it mattered in any way. I passed the time deep in thought, in fantasy lands of my own imagination.1 The physical world of recess had become dull, and I wanted no part of it.

Later, at another school, in grade 6, the same pattern applied. There were woods near that school, too, and at the beginning of the year we played in it. By winter the administration had decided this long-lasting tradition was too dangerous. They decreed that the teachers would now park their cars in what had been the bus driveway, and they turned the previous parking lot into the play area. It was a big rectangle of asphalt, which they eventually ameliorated by surrounding it with wire fencing. Clearly the most fun environment you could dream of. Those who liked basketball (this didn’t apply to me) could play it in one corner and that was about it.

My friend and I convinced our teacher to let us spend recess indoors, working on a project that involved drawing big posters, instead of going to play in that farce of a schoolyard.

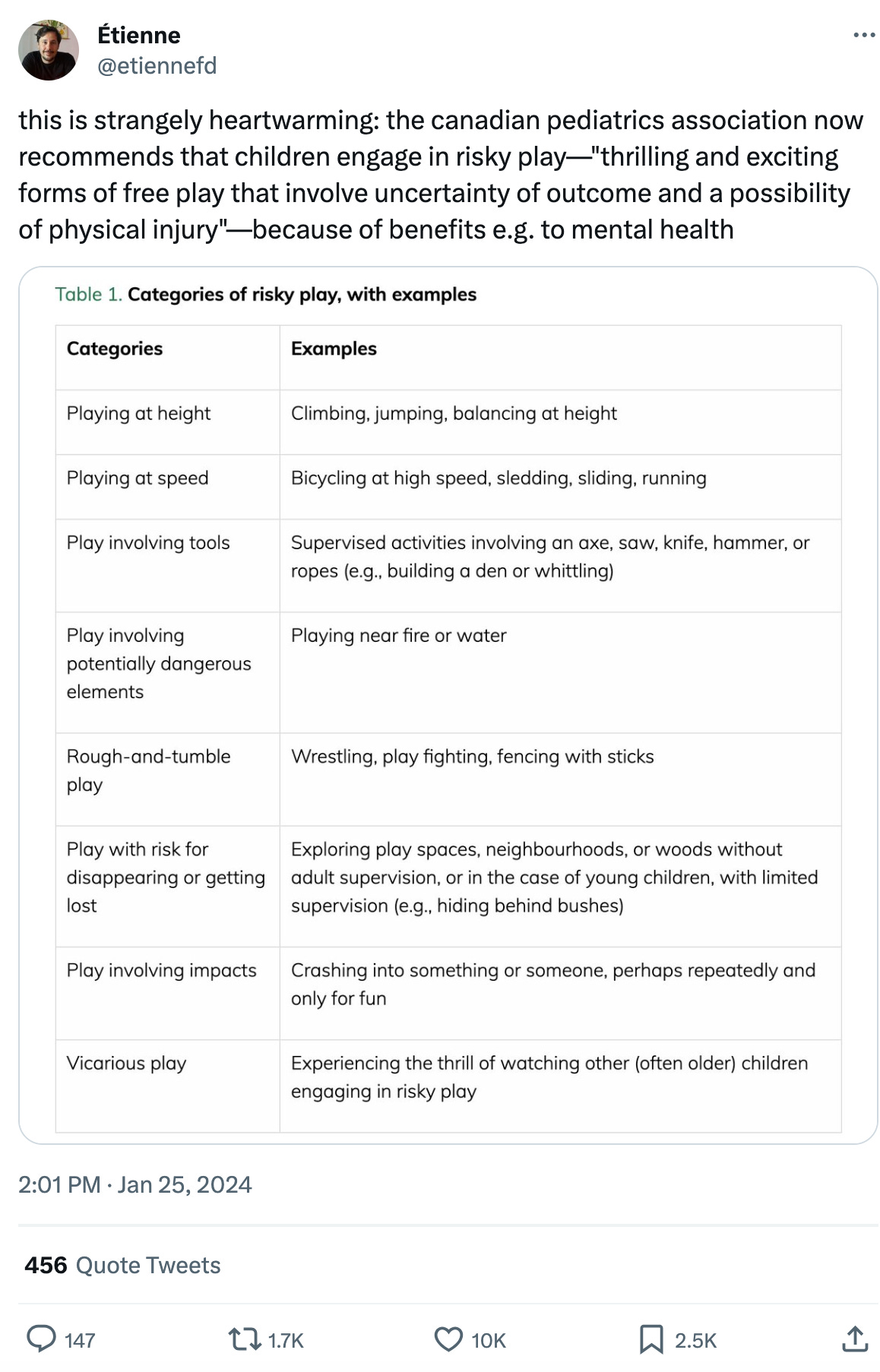

I have been diving into my old elementary school memories because of recent news from the Canadian Paediatrics Society. If you have heard of it, it may be because of the following tweet, which became (by some metrics) my most popular tweet ever:

(Those who want to dig more into this can read the full report by the Canadian Paediatrics Society — not the Canadian Pediatrics Association like I wrote, oops — here.)

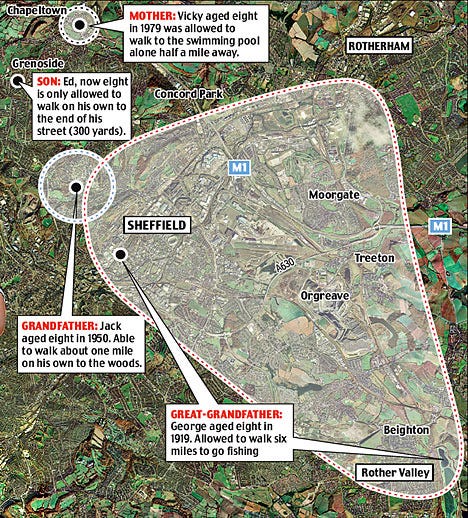

I’m pretty happy this happened. It seems true that society has moved towards an overabundance of caution around kids. Every now and then this map makes the rounds, showing how restricted the range of 8-year-old children has become over the course of a few generations:

The norms have changed; the laws too. I greatly enjoyed reading this 2022 post from Zvi Mowshowitz on how car seat laws can be seen as contraception: they make it more expensive to have kids, especially more than two kids, since you typically need a larger car for the extra car seats. And therefore such laws probably reducing fertility in exchange for a marginal improvement in safety. After I read that the first time, I looked up what the law was where I live. Since 2019, it mandates that car seats are necessary for all children aged 8 and less, which Zvi appropriately calls “flat out nuts.”

These, and the story about my schoolyard woods, are only a few examples of the pervasive safetyism that seems to now permeate Western societies, and which especially affects children since they are in no position to fight back.

But what’s most interesting about this is that… no one seems to want that? When poring over the replies and quotes to my tweet, it seemed to me that everyone agreed with the Canadian paediatricians. Not literally everyone, some people thought some of the items in that table were a bit exaggerated (like playing near fire), and some misinterpreted the argument a bit (believing it encouraged kids to actually seek out dangerous activities, when it simply says that kids shouldn’t avoid activities just because there’s some reasonable risk). But overall the sentiment was the same everywhere: Of course we have to let kids be kids and do activities that carry some risk; of course it’s fine if children get mildly injured because they crashed into one another repeatedly and only for fun. After all, that’s how we learn our limits, and how to assess risk, and how the world actually works.

So why did the Canadian Paediatrics Society feel the need to point that out?

The reason, obviously, is that no one wants “safetyism” in the abstract, as a vague phenomenon affecting all of society, but everyone wants “safety” at the level of individual actions. Even more importantly, everyone wants to avoid looking like they’re causing risk to other people. When those other people are adults, they can at least protest; we have strong norms on individual freedoms. But kids have no choice but to comply.2 And so we get things like teachers who banish the most fun part of recess, because how bad would it look if a child seriously injured themselves in those woods? Nobody wants to argue with an angry parent about that.

This is a beautiful illustration of a common issue: individual actions that separately make sense but collectively make things worse. A classic coordination problem. Some have given this phenomenon a metaphorical name and called it Moloch. A god of child sacrifice. Fitting.

Defeating coordination problems is hard, though doable. One could say that that’s the whole point of having any sort of established authorities: so that they can override a collection of individual decisions and steer everyone in the right direction. In this case it is the expert authority of paediatricians, and I’m glad they’re using it well. With any luck this will catalyze a vibe shift, in which I will perhaps have played a small part.

The benefits, if this vibe shift materializes, could be enormous: more children, and also healthier children, who go outside more, and play on iPads less, and suffer less from anxiety and depression. And therefore, a few years down the line, healthier adults. Perhaps adults who will be less prone to implementing harmful safetyism in all spheres of their life.

I don’t know if that’s what we’re headed for, but I’m hopeful. This was truly heartwarming news. In fact it even greatly increased my own desire to have kids, and I finally stopped procrastinating and called the adoption office today. Maybe, a few years from now, I can send my own kid playing in the woods with no adult supervision.

Also because apparently I didn’t really have any friends in grade 4. Sad.

A related, separate problem is that of taking kids seriously, as actual people who can make decisions for themselves. It seems possible that a similar trend has made us move away from that, but I’m not sure why.

My father and stepmother died 7 years ago in a car accident, leaving me (at the time 27), Lucas (26), Theo (6), and Arthur (6), four brothers (we don't believe in the concept of _half brothers_) that were left to fend for themselves. We're, respectivelly, 34, 33, 13 and 13 now.

Lucas took into his own hands the raising of the kids, even doing a legal stunt to keep the parenting rights — the laws say the grandparents keep the kids and, well, Lucas didn't do law school for nothing.

While the kids' parents raising was very different from mine and Lucas' — our mother, dead in 2007, was much more into the "let the kids play" than Andreia, father's new wife — so when everyone was gone Lucas insisted in changing this educational model. The kids were meant to break their arms, scrape their knees, hurt their feet and come home covered in mud after a rainy day. That, for Lucas, was safe play. Staying at home playing videogames was dangerous.

Now, both the kids — taller than Lucas and I, in the start of dreaded teenage years — do _everything_ by themselves. They ride their bikes to school and back, they get groceries at the market, they visit the nearby skatepark, they go to their english classes. We're in Brazil, so this kind of independence is difficult to see and it's also dangerous.

But danger, as Lucas says, teaches. One of these days Theo fell from his skateboard and hurt his hand and knee. He walked home, bleeding a little, to take a shower and tend to the wounds. He didn't cry or complain "I'm hurt, I fell". He was angry because the road had a bump, and now his hand would hurt for some days. And that's it, let's throw in a bandage and good luck, that's life, let's go.

I'm proud that they are growing tough and ready to face some of life's challenges, and pretty sure they are tougher than most of their friends. I hope we're not raising boys that are afraid to cry or that think feelings aren't nice. Teenager years suck and Lucas and I have no clue what we're doing — we never chose to have kids and now we act as father-and-father to our brothers.

All we've got is hope.

I grew up in the 70s and had endless freedom. I came home to an empty house when I was six because both my parents were working and travelled much further than the grandfathers in Sheffield.

I wanted my kids to have the same freedoms as I had but they were just completely uninterested. We specifically moved to a little housing development with dozens of kids to play with. It was next to a forest on the side of a mountain but my kids never left the house ever because of video games. No kids ever left their houses.

Imagine what the next generation of parents — the ones who never left their houses as kids — will be like…