Do Not Befriend the Problem—Slay It

AWM #76: In science, politics, and other problem-solving fields, longevity is not a sign of success ⏳

In 1990, Canada was embroiled in a constitutional debate over the status of its only French-speaking province. For decades, Quebec had hesitated between independence from Canada, status quo as a province equal to the other nine, or some compromise in which it would gain unique privileges. As you might imagine, the other provinces weren’t in love with the idea of granting privileges to Quebec only, and as the debate reached its climax in the late 1980s and early 1990s, pro-independence sentiment was on the rise.

A new political party was formed in Ottawa: the Bloc Québécois would represent the interests of the pro-independence Quebecers within the parliament of Canada. Its leader, Lucien Bouchard, said that the party's success “would be measured by the brevity of our mandate.” Ideally, Quebec would secede within a few years, and as a result there would be no more need for a pro-independence party in Ottawa.

But Quebec did not secede from Canada, and 32 years later, the Bloc Québécois still exists.

So, should we say that the Bloc Québécois is a failure? The Bloc didn’t manage to make independence a reality, but it’s doing pretty well as an organization. Nowadays, with secession very much not on the radar, it has recast itself as a regionalist party that defends Quebec interests at the federal level, and has been fairly successful at this task.

This doesn’t prevent its opponents from pointing out the “success = you shouldn’t exist anymore” thing every once in a while, as if it were a curse that was placed on the party from the start. And in a way, these opponents are right: the party failed, and now its goals have become ambiguous.

Therefore, in terms of political strategy, Bouchard may have made a mistake when he said this. Yet it was refreshingly honest. The Bloc Québécois was trying to solve a problem, it was upfront about it, and it committed to trying to solve it really fast.

This sort of thinking should be way more common than it is.

Imagine that a genius biologist came up with a pill that worked really well against most forms of cancer. Something clever, yet simple, that we can cheaply administer to every cancer patient, beating the disease in a matter of days. Within a year, there is no more cancer on planet Earth. Great news for everyone, right?

I bet you haven’t thought of one specific population: cancer researchers. There are people out there who have devoted their entire lives to studying cancer. They have spent decades perfecting their skills and publishing dozens of papers. Now, not only all of that was for naught (obviously, our genius biologist didn’t read any of those papers), but also, the researchers are out of a job and a purpose in life! Isn’t that sad?

No, of course not. It would be ridiculous to bemoan the fate of cancer researchers in the face of all the suffering that cancer patients are now freed from. As Eliezer Yudkowsky puts it:

If you work at creating a cancer cure for twenty years through your own efforts, learning new knowledge and new skill, making friends and allies—and then some alien superintelligence offers you a cancer cure on a silver platter for thirty bucks—then you shut up and take it.

And yet something like this seems to occur all across the sciences. In their review of a major paper on obesity, the writers at Slime Mold Time Mold find that the 43 (!) authors of the paper… don’t seem like they actually want so solve the obesity epidemic. Their paper is defeatist, pessimistic, unclear on what to do next. Why? Perhaps because to them,

“more research is needed” is the happiest sound in the world. Actually solving a problem, on the other hand, is kind of terrifying. You would need to find a new thing to investigate! It’s much safer to do inconclusive work on the same problem for decades.

Erik Hoel wrote about the same idea in the context of COVID research. To be considered a successful scientist, you need to win at the “Science Game™.” The Science Game™ consists of manipulating data just enough to get a result that can be published in a good journal and, therefore, win grants that allow you to keep playing the Science Game™. This means that the best kind of the science is the kind that you can vary endlessly without ever solving anything.

For instance, if you’re a virologist, there’s only so much you can learn and publish from studying a specific kind of bat coronavirus. So in order to keep playing the game, you start creating variants of the virus. You do gain-of-function research, in which you try to make your virus do new things. Like infecting human cells. And then maybe your virus escapes and causes a global pandemic. Whoops!1

The Science Game™, whether in virology or in obesity research, occurs due to the incentive structure of academia. Unfortunately, there’s no easy way to change these incentives. But perhaps we could at least recognize, like Lucien Bouchard did, that success should be measured by the brevity of a scientist’s career.

In other words, we shouldn’t particularly celebrate a researcher who has published many papers on a single topic. In fact, a long publication list should be a bad sign, unless you could show that the majority of the papers are breakthroughs that actually solved something and allowed you to move on to other problems. Since nobody has time to read all the tedious papers in a scientist’s CV, then a good heuristic would be to just give grants to whoever has published the fewest papers.2

Likewise, an elderly scientist who has devoted 50 years to lung cancer research shouldn’t be highly respected for “having improved our understanding of the cellular mechanisms of oncogenesis in blah blah blah.” He should be scorned for having failed to solve lung cancer even though he devoted a full half-century to the problem. A 25-year-old PhD student at least has the excuse that she’s just getting started.

I’m exaggerating, obviously. I’m sure lung cancer is a difficult problem that can’t be solved in a single lifetime. But actually, am I? Has a real effort to solve lung cancer without playing the Science Game™ ever been tried? How would I know?

The idea that success goes hand in hand with longevity applies to much more than science and politics. In fact, it has its origins in the very foundation of what it means for a piece of information to exist.

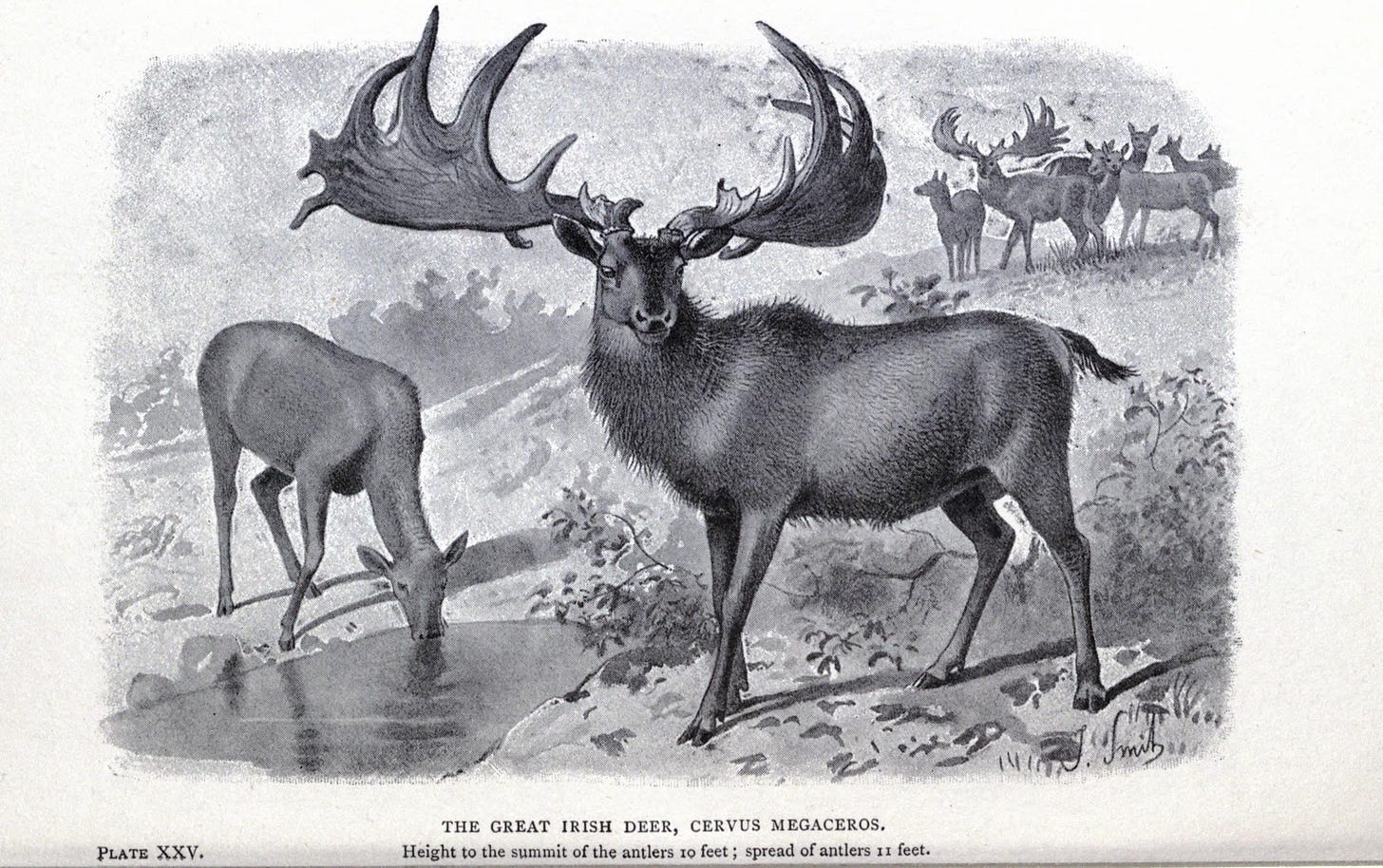

Darwinian evolution says that the organisms that pass on their genes are those that manage to survive and reproduce. The same idea (with some nuance) applies to memes. In both cases the implied assumption is that success means to keep existing. An organism that goes extinct, like the Megaloceros, feels like a failure. A meme that has endured for millennia, like Christianity, feels like a success.

But couldn’t we equally say that the Megaloceros was successful in its time, and that its extinction when the environmental conditions changed was “right” in some sense? Couldn’t we say that an ideology that has endured for centuries is a failure because it has kept morally abhorrent ideas alive, and prevented the rise of better memes?

I think that because we are the product of genes and memes that have kept existing, and because it’s better for us as individual organisms to keep existing, we intuitively ascribe higher worth to other things that keep existing. For instance:

A marriage that ends is considered to have failed, regardless of how happy the two spouses were while it lasted.

Many people intuitively feel that it’s better to spend $500 on a material good that they get to keep than an experience that will last only a night, like a fancy meal.

We admire — and consider more prestigious — institutions that have lasted a long time, such as universities, newspapers, companies, scientific journals, etc.

None of this is necessarily wrong. There is some value for a piece of information to have survived a long time: it means that it is tried and true, that it is “Lindy.” But even in those cases, longevity is not the thing we care about. It’s a heuristic, a proxy for what truly matters (usually something that boils down to increasing our well-being).

And to be clear, in many cases we do know that brevity is good! Plenty of things are designed to be ephemeral, from school to travelling for fun to some art installations. And our intuitions do not fail us for things that are not made primarily of information, such as food: nobody thinks that keeping a piece of chocolate cake in the fridge for years is better than eating it.

But when it comes to solving problems, whether in politics, in science, in technology, in business, even in art, it’s really fucking important that you do not become attached to the problem. The problem is not your friend. The problem is not a beautiful animal to be preserved. The problem is your enemy, it is a terrifying monster, and each year that you fail to slay it is one year too many.

That doesn’t mean, of course, that you should give up. It means that you should try way harder.

My understanding is that we still don’t know whether SARS-CoV-2 originated in a Wuhan lab or in wild bats, and we may never know.

At the extreme, imagine a scientist who has published a single paper, but one that contained the cure for cancer. We should give them enough grant money that they can retire!