A warning: This post contains abstract discussion of suicide, murder, the Holocaust, and other evil things.

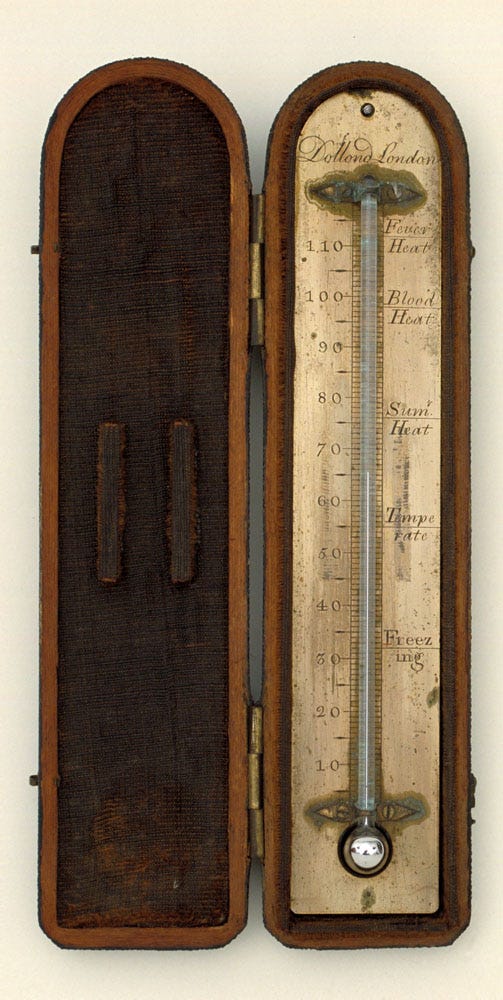

Whether you prefer Celsius or Fahrenheit, there’s no question that both systems have a significant drawback: they don’t represent natural quantities of heat. Instead they allow us to measure heat1 as points on an arbitrary scale that is divided (also arbitrarily) into degrees, which can be negative or positive.

In other words, 20 °C is not twice as warm — it doesn’t represent twice as much heat — as 10 °C does. Same story for 20 °F versus 10 °F. Also zero degrees does not mean zero heat in either scale, which is obvious if you consider that 0° C ≠ 0 °F. Zero heat, a point known as the absolute zero, is expressed as a negative number in both Celsius and Fahrenheit: −273.15 °C or −459.67 °F.

The scale that solves this is the Kelvin one. Twenty kelvins (written 20 K) really is twice as warm as 10 K, and the absolute zero is defined to be 0 K. Note that we don’t write 0 °K, nor do we ever talk of degrees Kelvin, because those aren’t arbitrary degrees. They’re regular units, just like kilograms, seconds, or inches. Except as a mathematical artifice, it makes no sense to describe anything as having negative kilograms, seconds, inches, or kelvins: in all these cases zero is the smallest possible quantity.2

Nobody uses kelvins in daily life, because most relevant temperatures would have to be expressed with three-digit numbers, and this would be cumbersome. (As I write this, it’s a sunny 274 K where I am.) But thinking in the Celsius and Fahrenheit scales can trick us into forgetting basic facts about the physical world. For instance, that cold and hot are not symmetrical. An object can have a temperature of 10,000 °C, but not -10,000 °C, since that would be below the absolute zero. But 10,000 °C (or K, since at that scale the difference matters very little) is still far from how hot things theoretically can get. In our current understanding of physics, the highest possible temperature seems to be about 142 nonillion kelvins, or:

142,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 K.Thus we can have practically infinite amounts of hot, but not infinite amounts of cold. The reason for this asymmetry is that cold is simply the sensation of having less heat than is ideal for our bodies. It’s just a lack of hot. There can’t be an arbitrarily large amount of a lack.

Good and evil work the same way. Good means whatever is valuable; in principle there is no upper limit. Evil, meanwhile, is a lack of good. The worst evil is just emptiness.

Is that true? Can there not be something more evil than nothing?

Intuitively, there seems to be plenty of evidence against what I just said. Consider pain: its absence isn’t good; it isn’t, by itself, pleasure or happiness; but it’s preferable to the presence of pain. Pain seems worse than nothing.

Consider this excerpt from the novel Unsong about the music from Hell:

“So?” asked Zoe. “Maybe the Hell music was just the total absolute absence of good in music.”

“No,” said Ana. “There’s good music. And then there’s total silence. And then there’s that. It’s not silence. It’s the opposite of music.”

“Unsong,” I suggested.

Consider suicides: they’re relatively rare, and they’re usually the result of some mental illness, but they’re evidence of people who prefer not to exist. People who, presumably, find their existence more evil than emptiness would be.

Consider the related argument on whether it’s morally permissible to eat meat: the vast majority of farm animals wouldn’t exist if we didn’t raise them for their meat. Widespread vegetarianism wouldn’t give pigs and chickens a happy life; it would give them non-existence. Therefore, whether vegetarianism is good or not depends on (among other concerns) whether the lives of industrially farmed pigs and chickens contain more evil than emptiness would. Many think it’s the case.

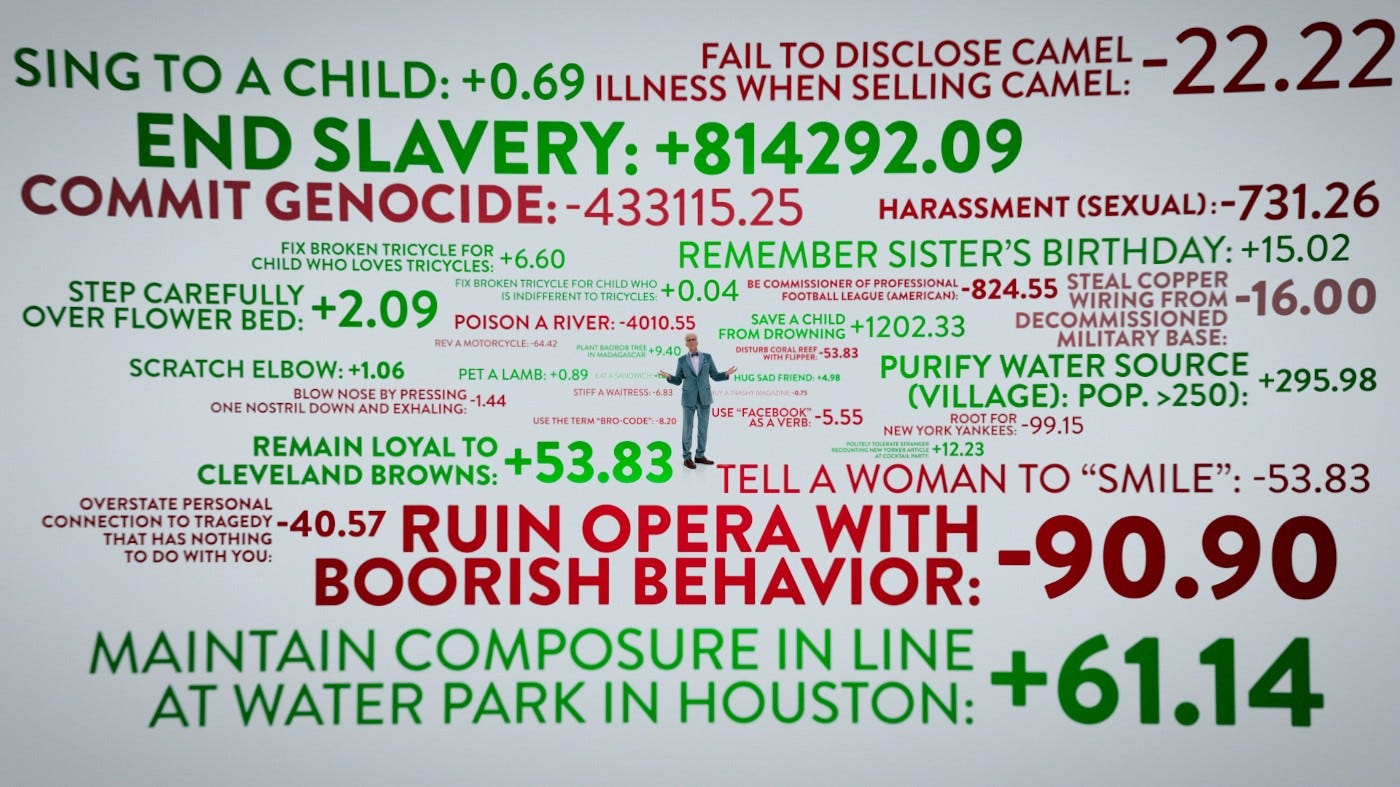

These examples suggest that a scale of good and evil should contain negative values. Something that is neither good nor evil, such as pure nothingness, would score 0 on the scale. Good things, like love, tasty food, or the life of a saint, would score positive points in proportion of how good they are. Evil things, like pain, depression, or the criminal career of a serial killer, would score negative points in proportion of how evil they are.

This is nicely symmetrical. But we saw above that the apparent symmetry between cold and hot is an illusion. Might it be the same for good and evil? After all, just like the temperature of everything in daily life is far from the absolute zero, human (or animal) lives all contain, by default, some good. Just like cold is a deviation from an ideal temperature towards zero heat, evil can be seen as a deviation from some normal amount of good towards zero good.3

So perhaps it makes sense to use an absolute scale instead. The Kelvin scale was created by shifting the Celsius scale 273.15 degrees so that 0 would be the lowest value. Similarly, we can shift our scale of good and evil by some amount so that the most evil possible thing becomes the 0 value.

What is the most evil possible thing?

Let’s brainstorm. Pain is bad, but it’s not the worst thing. Intentional pain, like torture, seems worse than accidental pain. Death is worse than torture, in large part because it is permanent. Murder is worse than accidental or natural death. Some types of murder seem more evil than others; for instance, most people would probably agree that cold-blooded, gratuitous murder is worse than a passionate murder to exact revenge against someone who murdered one of your relatives. All of these things pale in comparison to torture or murder applied to large numbers of people. You’re thinking of the Holocaust right now, and yes, that’s a strong contender for the title of single most evil act ever perpetrated by humanity (although it is by no means the only candidate among history’s many atrocities). But it’s easy to imagine something that’s theoretically worse than the Holocaust. Two Holocausts, for instance. Or three. Or as many as it takes to wipe out all 8 billion humans. Yeah, the death of everybody alive — in other words, extinction of humanity — seems like a pretty evil thing. It has the additional property that it would lead to the loss of all potential that humanity currently has. But there’s worse than that. Extinction of all life on Earth would be worse. The destruction of the galaxy seems worse, assuming that there are other valuable things out there, such as alien, possibly intelligent life forms. Multiply this destruction by the number of galaxies in the known universe, and we get something even more evil. Logically, then, the death of the universe as a whole might be the most evil thing, assuming there aren’t any other universes (in which case the death of all those universes would be worse).

An uncomfortable corollary of ordering things by evilness is that you could reverse the list and say it is ordered by goodness. Things that are very cold to us can still be compared according to how warm they are: liquid oxygen4 (90 K, i.e. −183 °C or −297 °F) is warmer than liquid nitrogen (77 K, i.e. −196 °C or −320 °F). Under the same logic, the Holocaust contains more goodness than the extinction of humanity. It’s not fun to look for nuggets of goodness in something as awful as the Holocaust, but they do exist. For instance, some people survive the Holocaust, whereas nobody survives global extinction. The Holocaust is therefore further away from the absolute zero of evil than global extinction is.

We could of course quibble on the exact ordering. I said that death is worse than torture because it is permanent, but what about a hypothetical scenario in which a person is made immortal and then tortured for eternity? Would that be worse than death? Again, suicides are evidence that some people prefer death to a painful life. At a larger scale, a hypothetical universe in which vast numbers of conscious beings are being tortured for eternity (we can call this “hell”) might be worse than a dead one.

Yet all these things still contain some nuggets of goodness, I think. (I write “I think” because I’ll readily admit that this is the shakiest part of my argument. Feel free to attack here.) One kind of goodness they contain is conscious experience, which I believe is positive even if it allows suffering. I’m also not sure that speculative “eternal torture” scenarios are logically consistent. Human minds and bodies contain a number of features to limit pain, like psychological shock, or the hedonic treadmill. After a while of suffering constant pain, we tend to become numb. In theory it might be possible with engineering to take that numbness out of the equation, but this would create a kind of being so psychologically alien to us that it becomes hard to say what is good and what is evil. I think.

So let’s assume you agree with my ordering, and let’s return to our scale of good and evil. We set the absolute zero to be the death of the universe. Elegantly, the most likely scenario for the fate of the universe is the heat death, in which the temperature will approach, you guessed it, 0 K. Our two concepts of absolute zero meet.

Just like it’s impossible to find heat in a universe at 0 K, it is impossible to find any nugget of goodness in a dead universe. Naïvely, such a universe may feel peaceful, or quiet, which are good qualities to seek in normal life — but it isn’t, because there’s no one around to benefit from the peace or silence. Desiring the tranquility of a dead universe because you’re stressed out would be like desiring a bath of liquid oxygen because it’s a hot summer day. Not a great idea in either case.

There is absolutely nothing valuable in a dead universe. No life, no consciousness, no beauty. It is pure cold. Pure emptiness. Pure evil.

The heat death of the universe is an evil that will engulf us someday, and there’s nothing we can do about it. Fortunately, there are still three reasons to rejoice.

The first is that the heat death is extremely far in the future. So there’s no point worrying about it.

The second is that the very concept of death carries a hidden nugget of goodness: it implies that there was life. We mourn our deceased loved ones, but we say that they enjoyed a good life, not that it would have been better if they had never existed. By the same token, a universe that contains people for a time, and then dies, is less evil than a universe that never existed in the first place.

Thus the true absolute zero is not heat death: it is non-existence. In something that does not exist, there is no good, there never was, and there will never be. But in something that exists, then good can flourish, even if there isn’t a lot of it in the first place.

And this brings us to the third reason to rejoice. Recall that hot and cold are asymmetrical: things can’t be arbitrarily cold, but they can be arbitrarily hot. Likewise, things can’t be arbitrarily evil, but they can be arbitrarily good.

In other words, you can never do too much good. You can always do something nice for others. You can always solve problems. You can always build useful or beautiful things. You can always have kids — new people who can enjoy the world — or help those who do. You can always contribute to sending humans to new planets and stars. You can always fill the universe, which outside of Earth is still rather empty and cold, with goodness and warmth.

Let’s get as far away from the absolute zero as we can.

More precisely, temperature measures thermal energy, which refers to the energy contained in molecules as they vibrate and move around. This is not quite the same thing as heat in THE strict sense used in physics — that would be the transfer of thermal energy. In colloquial language, saying that temperature measures heat is fine.

For temperature, 0 K is actually the smallest theoretical quantity. Experimentally we can cool down some matter to mere billionths of a kelvin above the absolute zero, but it’s not possible to reach zero exactly.

This is what a negative number is, by the way: a mathematical abstraction to describe a deviation towards nothingness.

> This is what a negative number is, by the way: a mathematical abstraction to describe a deviation towards nothingness.

Some explanation of this statement would be nice. Traditionally, 0 represents "nothing", and an increasingly negative quantity is getting further away from 0, not approaching it.