I Wrote Half a Book About Phantom Islands and Then Discovered I Was Scooped Seven Years Ago

Whatever, my book will be better anyway 🏝️

A phantom island is a cool name for a type of cartography error that crops up several times in the history of mapmaking: believing that an island exists where none does. The causes are diverse, and studying them is a great way to get immersed in the history of the discovery of the world.

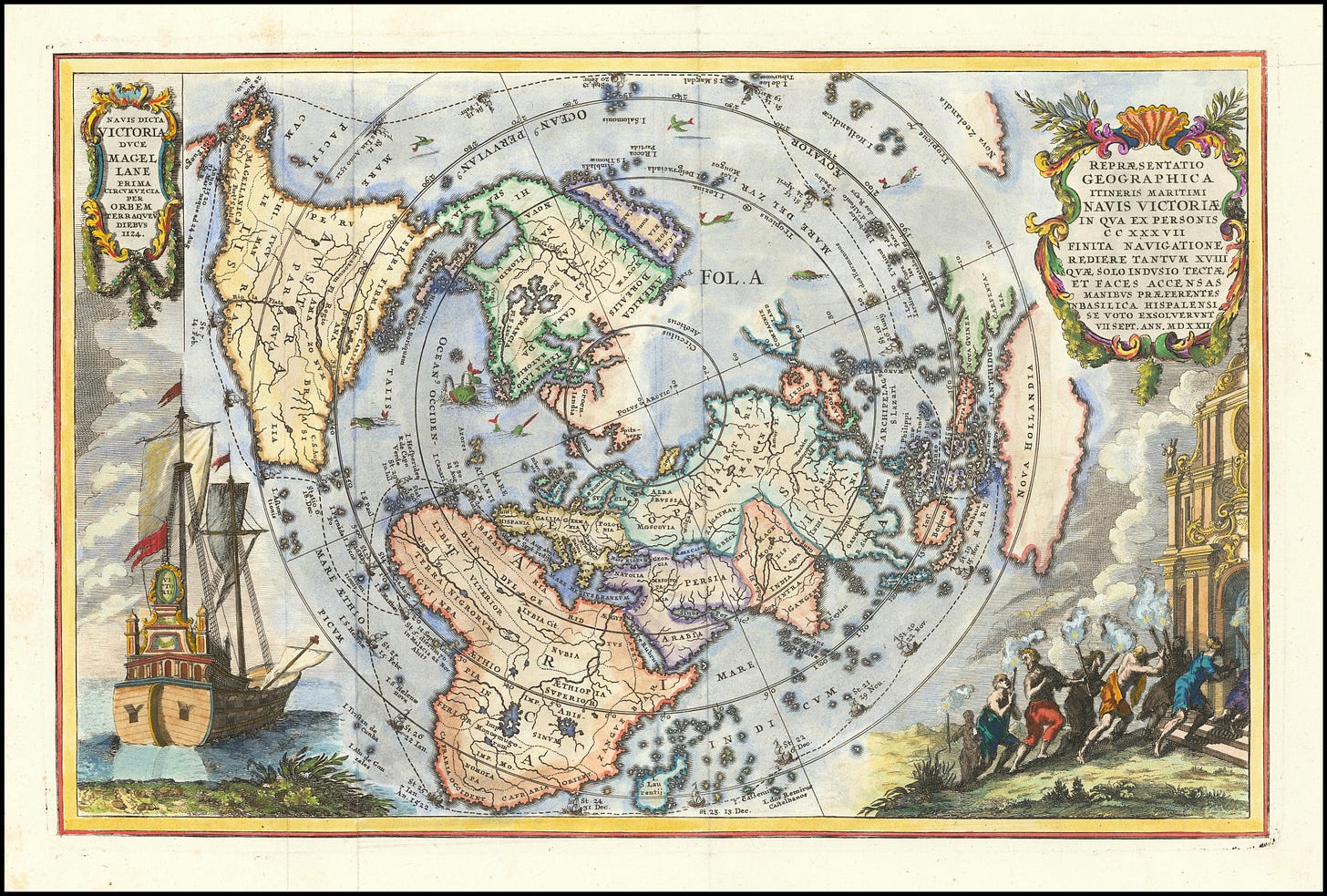

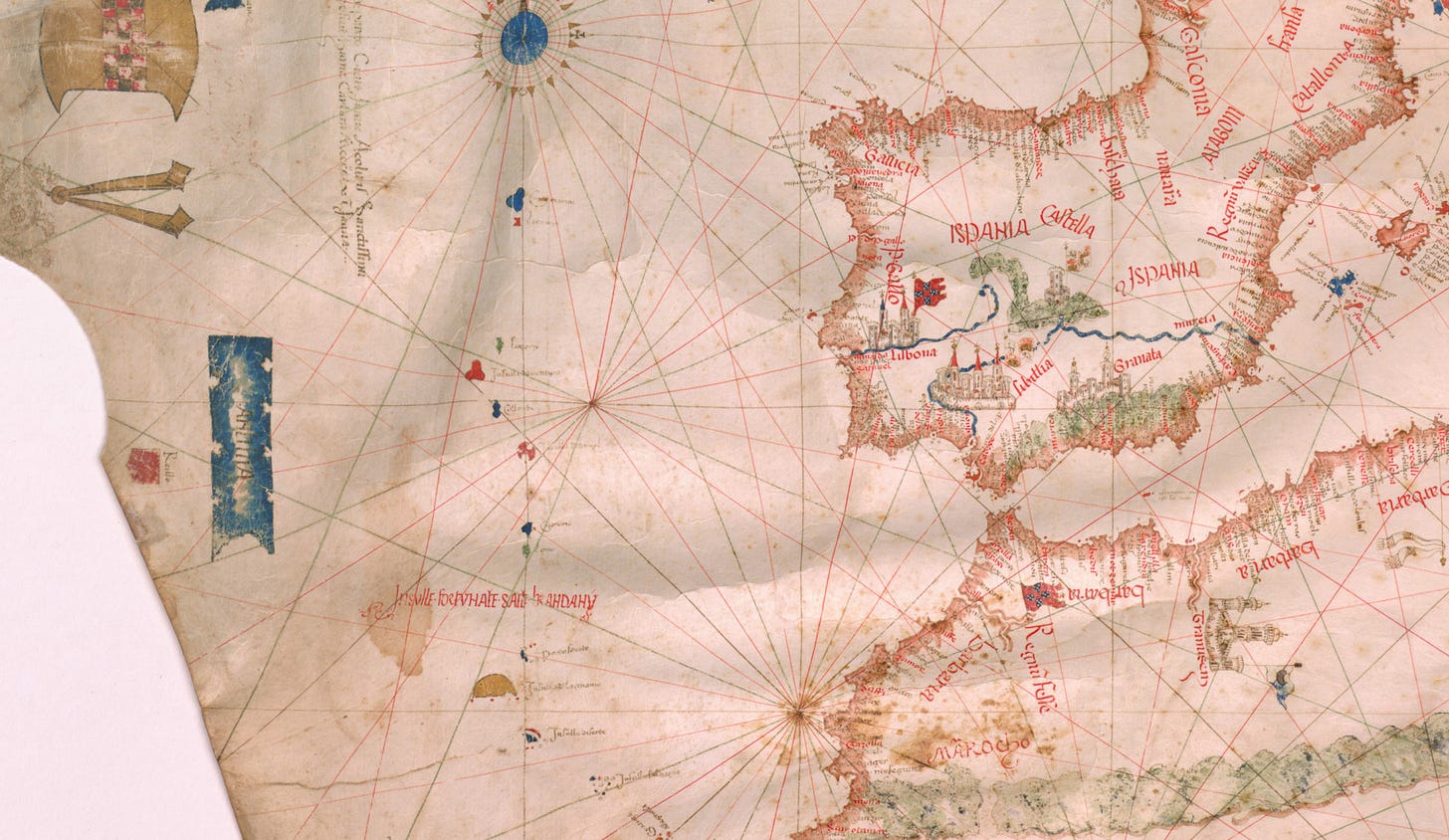

Often, a phantom island is born out of a simply clerical error. A ship passes by a real island at 2°S of latitude and 5°38’W of longitude, near the coast of Africa, but the captain mistakenly records the coordinates as 2°S and 8°W. Later, the ship’s logbook is used as data by a mapmaker in Europe, who places an island at 2°S 8°W. Other mapmakers — the members of that profession don’t tend to travel much, somehow — eventually copy it, and for centuries St. Matthew Island appears on various maps of the Atlantic ocean, until one day another ship, equipped with more modern gear, definitely proves its non-existence.

Such confusion with other islands (or shoals, or rocks, or reefs, or any other hazards that it might be useful to put on a map) is common; but another cause can be illusion, like the fata morgana mirage, which creates the appearance of land above the horizon. Icebergs provide another easy way to imagine the existence of an island. If the sailing conditions aren’t that great, if there’s a bit of fog, the crew might be excused for not making extra sure that that landmass on the horizon is actually Dougherty Island and not a mass of ice that will have melted long before it is added to a nautical chart.

Yet another source of ghostly islands is incomplete exploration, and here you’ll excuse the Eurocentric perspective of this post: it is obvious that the people of the Kingdom of the Great Joseon knew that Korea is not an island, or that the indigenous inhabitants of the West Coast of North America knew that California also isn’t; yet for a long time both were represented as disconnected landmasses on European maps.

Other phantom islands are deliberate fabrications. When vast swathes of the world are still unknown, it is easy to invent Crocker Land (and name it after your financial backer, Mr. Crocker from San Francisco) to obtain more funding to go explore the Arctic. Of course, it might be hard to keep your fraud undetected once a rival explorer visits the area, so be careful.

Also intentionally fictional, but more whimsical, are islands that were identified as the location of stories, legends, and myths. You’re thinking of Atlantis, although Atlantis never, I think, appeared on any serious maps. A similar island that did, however, is Antillia, where there supposedly resided seven bishops in that many golden cities. Cristopher Columbus is rumored to have expected to see it, when he crossed west. He never did, of course, but the name lives on in what is now known as the Antilles.

Finally, some phantom islands may actually have existed, but don’t anymore, destroyed by the vagaries of the Earth and its oceans. Thus Kianida, in the Black Sea near Istanbul, which appears on some medieval maps, has been hypothesized to have sunk at some point due to something like an earthquake. More amusingly, the island of Bermeja, which appears near the coast of Yucatan on most old maps, is said to have been deliberately erased by the CIA circa 2007 to prevent Mexico from claiming an oil field as part of its territorial waters, though of course that might just be a modern-day legend — a conspiracy theory.

The above is but a sample of the many stories that surround phantom islands.

When I learned about them, I think in 2019, it was immediately obvious that they were a theme of unusual narrative richness. I had just read one of my favorite books, the Atlas of Remote Islands, which tells short stories about 50 real islands. So I decided to write the same thing, but with 50 phantom islands.

(Conveniently, if you exclude totally mythical islands like Atlantis and group a few minor and nearby islands together, 50 is approximately the number of phantom islands that have ever existed. Or, well, not existed. You know what I mean.)

I don’t work on this book often. But as of today, I am happy to report that it is halfway done: I’ve written 25 stories.1 Most of them are somewhere between fiction and real events (though in all cases, real events surrounding fictional places, which complicates matters somewhat). Sometimes I romanticize the real life of the explorer who spotted them; sometimes I write completely made up stories, using the phantom island as an excuse and starting point. I’ve explored many genres: there’s a sci-fi simulation story, a pastiche of the great novel Salammbô, a couple comedy screenplays, a Norse saga. I’ve been having great fun with this project, though I never expected that I’d still be working on it 4 years after I started. Or that there would still be 25 more stories to write after that.

Nor that I would discover, in 2023, that someone else had written and publish something that is very close to the book I’ve been slowly writing.

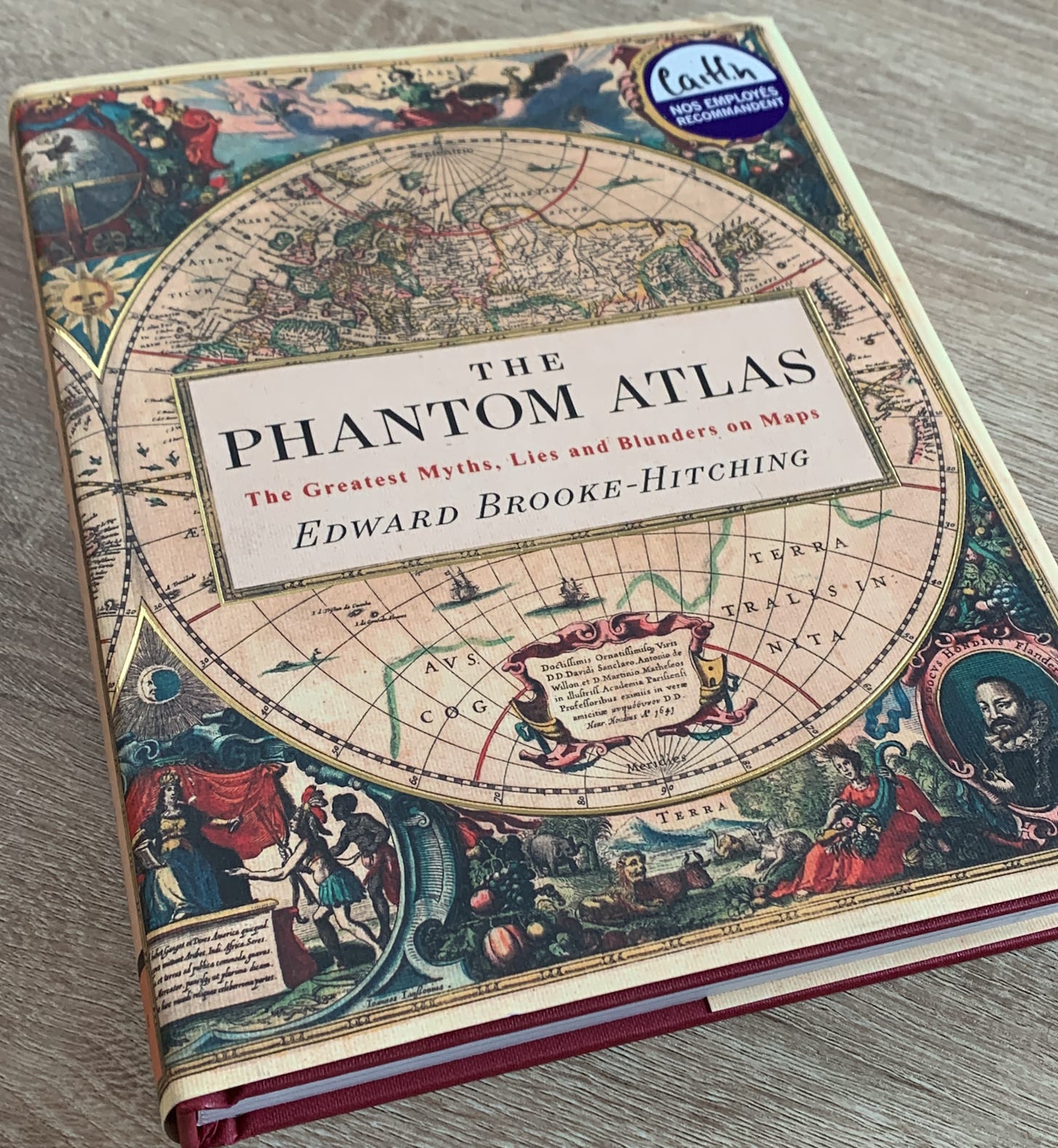

It’s called The Phantom Atlas, by Edward Booke-Hitching, and it looks like this:

Rarely has a book felt so me. I went to buy it at the store on the day I learned of its existence. Leafing through it, I saw something you might recognize:

That’s right — it includes a catalogue of the sea beasts of the Carta marina — the very monsters I use as a logo and section separators!

Which is fine, of course. The Carta marina is famous, it basically founded the genre of maps displaying random monsters all over the oceans. It’s very cool to see them there and read the descriptions.

Most of the book, however, is more or less what I had in mind with my project: a list of phantom islands, with examples of maps where they appear, and a little bit of storytelling. The main difference is that this book is meant as nonfiction (well, you know, nonfiction about fiction) whereas I don’t care much about my stories being true.

To be sure, that is a significant difference, which is good, because otherwise I might have been compelled to give up. It is a pretty weird feeling to see something similar to your pet project completed by someone else. Of course, it doesn’t take exactly the shape that mine would — nobody else can write the book I want to write. But I can’t help but think about the similarities, and about ways to make my project more unique. I’ll probably second-guess myself when I write the second half of the book; will my stories be distinct enough? On the bright side, I now have evidence that writing on phantom islands was a good idea.

Also — I’m really glad I learned about this book now, when 25 stories have been written, as opposed to 2016, when The Phantom Atlas was first published. Had I known of it, I would probably never have gotten started.

But the main reason I have to keep going might be that… The Phantom Atlas is kind of boring?

It’s a gorgeous book, to be sure. But — with apologies to Mr. Brooke-Hitching — the stories it tells feel kind of lifeless. They’re competently written, they’re informative, they say what they need to say; and yet they’re missing some sort of spark. They’re a bit too encyclopedic, perhaps.

I don’t really know why I feel this. One possibility is that I’ve been thinking about phantom islands for so long that I now have extremely high standards. Maybe I would find the book delightful if this were 2016 and I were reading about phantom islands for the first time.

The other, more intriguing possibility is that this book shows the limits of nonfiction. I’ve always had more trouble reading nonfiction books compared to fiction. I find that peculiar, in a way — I value knowledge of the real world quite a lot, while I don’t care about fictional universes at all. I suppose that fiction, freed from the constraints of truth-telling, is just more optimized to be interesting. But also, learning about the world can be done in a variety of ways, and storytelling is seldom the most efficient or pleasurable one, probably because real stories are always imperfect. I like reading an info-dump like Wikipedia more than I like reading (most) nonfiction books.

The Phantom Atlas tries to tell nonfictional stories. In theory this should be easy: the stories around phantom islands are fun and interesting by default. But in practice it doesn’t work that well, and I think it’s because phantom islands are already fictional. The point of reading about them is to be amazed and inspired, which is, of course, the point of fiction in general. Treating them as an encyclopedic subject is sort of pointless (unless you’re writing in a literal encyclopedia).

So I’m going to keep writing my book. Hopefully it has some of that missing spark of life; with any luck it will eventually amaze and inspire. I’ll let you know when it’s done.

I am new to your work (and have read just two of your posts), but your style is delightful. And I am sure your book about non-existent islands will be, too.

well, if you publish it (in english), I'll buy it.