Tomorrow I leave for a vacation in Mexico City. It’ll be the first time since 2017 that I’m visiting a country I’ve never been to before. I expect it’ll inevitably trigger the same “Why do I travel?” questions I always get when I’m in a touristy place.

Despite the clear social desirability of traveling for pleasure, the answers are far from obvious.1 Being a tourist imposes many costs. It is, of course, financially expensive. It takes a lot of time. It is usually a cause of personal discomfort, sometimes extremely so. It generates high carbon emissions. When it becomes mass tourism, it can have detrimental effects on local environments and populations.

For all these costs, you’d think the benefits must be worth a lot. But what are they, exactly? Travel was once the only way to see the world, but now we have videos and Google Street View. Any popular monument you could visit, you have already seen in pictures a thousand times. The homogenization of culture means that a lot of things are the same all over the world — hotels, airports, museums. You can get good Japanese food outside of Japan. You can meet people of different cultures in any large city.

I distinctly remember an episode from some years ago. I was walking on my own on the Greek island of Santorini, which has a severe case of mass tourism, and wondering, “why the fuck am I here?” The entire island was so overrun by foreigners that it didn’t feel real anymore. It was a fake place, full of people like me who had been lured by promises of quaint blue-domed churches and pleasant Mediterranean weather, and had gotten both, but at the cost of something deeper. I felt shame.

And yet — I have extremely fond memories of Santorini. I was there with friends. The weather was glorious, the blue-domed churches beautiful, the ancient ruins fascinating. I later wrote a short story I could never have if I hadn’t spent some time thinking about the tale of the catastrophic eruption 3,600 years ago, and seen the remnants of the destroyed Minoan civilization.

The shame was misplaced, and in truth, quickly dispelled.

Most people like to travel, so it’s not like “tourism is good” is a particularly heretical opinion. But it’s one of those cases where it can seem fashionable to be contrarian, for the reasons cited. So consider this a meta-contrarian essay. One that lives on the right side of the bell curve, claiming that the dominant opinion is correct, and explaining why.

Why is it good to be a tourist? First, let’s get some of the obvious answers out of the way, such as the fact that traveling can give you access to

pleasant weather.

I’m guessing this might be the top reason why people travel, at least the people who live in places with harsh winters, like I do.

I used to cringe at the annual migration of snowbirds, those people who leave Canada and the northern US to spend the winter in Florida or other warm places. But not too long ago I spent part of an autumn in Texas, and I sunbathed a lot.

I have a draft of another post about the relationship between weather and climate on one hand, and happiness on the other. I haven’t reached any strong conclusions yet, but I suspect that the impact of climate on happiness is usually overstated at the scale of years — but not at the scale of weeks and months. In other words, it seems likely that moving to a warm place permanently won’t make a person happier on average; but being a tourist to a warm place every winter will.

Closely related to weather is another obvious reason to be a tourist: it allows one to visit

natural environments

that may otherwise be impossible to access at home, such as beaches and mountains.

There’s not much to add here. If you want to be on a beach and there are no beaches in your immediate vicinity, then the solution is pretty clear. But a lot of travel involves no beaches, or involves seeking beaches that are different from the beaches one is used to.

So what else is there? At the risk of appearing cynic, one answer is certainly that travel is associated with

prestige.

Think of how people mention their trips on their dating profiles. Think of how it seems normal to ask people around you where they’re thinking of traveling for their next vacation.

Tourism, because it is costly, is a sign of belonging to a social class that can afford it. It is also a signal that is difficult to fake. I’m guessing few people travel with the explicit goal of increasing their own status, but I do think that many travel because they more or less consciously think they should be the kind of person who travels.

Is this bad? I don’t really think so, because, as we’re about to see, there are many genuine benefits to being a tourist. Status games are unavoidable anyway, so we might as well pick those that actually provide us with valuable experiences. And there’s a dimension of self-love to status games. I do feel more like the person I want to be when I travel. That’s true even if I recognize that it’s mediated by my social environment.

But why might I feel more like the person I want to be? I think it has a lot to do with

stepping out of one’s comfort zone.

Even though I’ve lived abroad and traveled a lot in the past, including in such exotic locales as the Palestinian Territories, northernmost Sweden, and Edmonton, Alberta, I feel nervous about my trip to Mexico tomorrow.

I think the nervousness will always be there. And I think that’s good. Travel should be a little nerve-wracking. A big part of the point of tourism is to put oneself in a situation that’s new and partly unknown. That allows us to avoid overfitting and generalize better about how the world works.

I always feel more like the person I want to be when I do things that are nerve-wracking. Talking to strangers. Public speaking. Sending out essays to hundreds of people.

Traveling is great because it forces you to do several nerve-wracking things all at once. You have no choice but to figure out how to move around, communicate, get money and food, and so on, all of that in an unfamiliar environment. When you come back, you are likely to be a more knowledgeable, autonomous, powerful person.

In fact, this generalizes. Travel is really good as

a forcing function

for many things you might care about but aren’t able to do in your daily life.

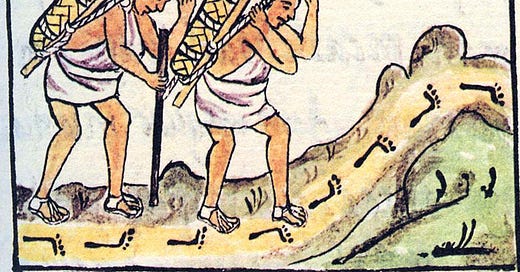

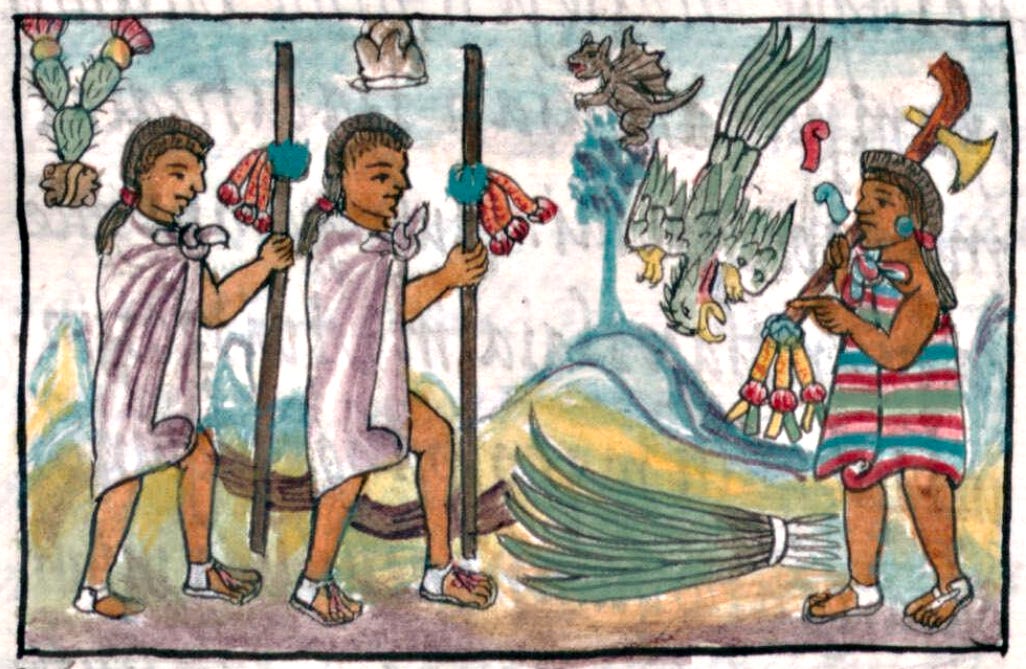

For instance, maybe you nurse a natural curiosity for ancient pre-Columbian civilizations, like the Aztecs and the Mayas, and yet you’ve never really taken the time to learn about them properly. You could read books and watch documentaries, but for whatever reason, you haven’t. Travel to Mexico, visit some ruins, a museum, and you will be easily surrounded by information about those cultures: you’ll have no choice but to learn.

The clearest example of this, of course, is language learning. But you can design a forcing function around anything. Want to try being vegetarian? Travel to a country where they eat little meat. Want to cast off a social media addiction? Put yourself out of a data plan in a foreign land, and fill your days with sightseeing instead of looking at your phone. Want to finish writing your novel? Travel to a quiet spot with no internet connection.

One reason that tourism is a good forcing function is that, as mentioned, it requires us to commit both time and money; it’s not easy to back out. But the other reason is simply that it is immersive, more so than most activities. That is to say, it is

a rich, multisensory experience.

Yes, you can learn about, say, the Eiffel Tower from pictures and videos and Wikipedia articles and perhaps even a 3D model of the monument… but none of these are even close to being a substitute for actually being there. Because when you’re there, all your senses are stimulated at once, and all of them are stimulated more richly than any simulation could.2

There are always a myriad of details about each place that can’t be captured in a book, video, or simulation. An appreciation for terrain and geography. What the soundscape is like throughout the day. Infinitely many angles of view, including the ugly ones that are never captured on photographs.

It’s the same as Zoom vs. in-person conversations, really.

The consequence of the forcing function and the multisensory aspect of travel is that despite the huge offer of media and learning materials of all kinds, tourism remains, like it used to be, an excellent way of

learning about the world.

It would sound obnoxious to claim that because you’ve spent two weeks in Israel and Palestine, you now understand the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.

But also, it’s true! Being a tourist is not necessarily a substitute for careful study, and certainly not a substitute to being from there, but I certainly think I can say less dumb things about the conflict after having visited. Just knowing, say, how one gets from Jerusalem to Bethlehem by bus, what the distance is, what the people on the bus look like, what the process of crossing the border is — it all makes the entire thing far more concrete.

We overstate how easy it is to learn things. I mean truly learn them, in depth. What we learn is always a major simplification of reality, by necessity. Whatever you see on your travels is also a partial picture, but one of another, entirely different kind. That’s worth a lot.

This post is from a day before a big international trip, and years after having been outside of Canada and the US. Perhaps I will come back from Mexico feeling that it was overrated. I do have the occasional worry that tourism will eventually cease to be valuable to me at all.

But right now, I doubt it, I’m looking forward the trip, and I’m enjoying the (manageable) nervousness. The next two weeks should be fun. See you soon.

I specifically do not mean “travel to see friends or family,” which is more about meeting certain people than being in a particular place. Neither do I mean any form of traveling for work, which of course comes with its own justification.

Perhaps future simulation technology will get there, but we’re a very long way from it.

Whoa, I just passed through Mexico City! I was on a layover to Puerto Escondido. I literally started your essay on the tarmac before takeoff and finished on the tarmac after landing.

Have a lovely trip! Learning about other people’s cultures broadens horizons, opens the mind. For some countries, tourism is their major way of stimulating the economy too.