Is It Worth Fixing Science?

AWM #55: Quick thoughts on why science may not be worth the trouble, even though I think it is 🧑🔬

Readability. As some of you know, I’ve spent a good chunk of my time since September working on JAWWS, the Journal of Accessible and Well-Written Science—not actually a journal (yet!), but a general research project to improve writing norms and readability in academic papers.1

Institutions. To work on JAWWS, I’ve received funding from Alexey Guzey’s organization New Science, which wants to reform scientific funding and institutional design. They seek to create a way for scientists to perform research outside the dominant model of academia.

Open access. For a few days now I’ve started getting involved in a new organization, called OpenAccessDAO (or OADAO, a nice palindrome!) whose initial goal is to liberate paywalled academic work. It began with a tweet from David McDougall about acquiring all the science journals, and now there’s a huge community trying to determine how exactly we should improve access to science.

These are the initiatives to improve science that I’m personally linked to. There are many more, trying to solve various parts of the big puzzle of academic science.

Will any of them succeed? Maybe. Science is a slow-changing world with fucked-up incentives. Many have tried to fix it, and many have failed.

Do we want them to succeed? I’m tempted to say, obviously. But I’m intrigued by the possibility that correct answer is no. What if they broke something inadvertently—or worse, what if improving science was bad?

The title of my essay is a question to which my answer was, and remains, “yes.” But I want to examine ways in which the answer might be “no.” Here are some hypotheses with quick thoughts on each.

Science works fine as it is; it would take too much effort to improve

Despite all its flaws, science produces still new knowledge. It could produce new knowledge more efficiently, but getting there would take a lot of the time of energy of smart people who could have more impact somewhere else, for instance doing basic science or whatever 80,000 Hours has identified as a pressing problem.

The truth of this depends on what the improvements would need to be. From one angle, fixing science writing style, for instance, seems ridiculously easy—I’ve identified several very low-hanging fruit that would take virtually no effort to apply by scientists. From another angle, everything in science is stuck in social norms, and those are very difficult to change.

Science can’t be reformed for structural reasons

Basic science is a valuable but also very unpredictable endeavor. You can never know if you’re going to get some applications from it. You can’t reliably make money from it. As a result, it’s difficult to get private actors to fund it, except in limited capacity through philanthropy. Governments have to step in.

This may mean that there’s always going to be a problem with funding science. Maybe the properties of the institution just prevent any efficient way to reform it. Because science papers vary in quality, there’s always going to be a need for journals to curate the best ones and grant them prestige. Because science is complex, there’s always going to be difficult jargon.

This view seems wrong to me—science has evolved somewhat haphazardly, surely we can be more imaginative than declare that what exists is the best that can be done—but I guess it’s possible.

The bad parts of science serve some unknown purpose

In recent years I’ve become quite sympathetic to arguments of the form, “If we don’t know why something exists, then we shouldn’t remove it,” also known as Chesterton’s fence. It’s often the case that something (e.g. a cultural practice like telling the future from bird augury) evolves to fill a need in a way that is not transparent. Later “smart” “rational” people can be tempted to replace it with something else, to disastrous results.

I don’t think there’s anything like that in the current state of academic science—but of course I would say that!

There’s a risk of lowering the status of science

Science, like art, is fueled with prestige. To separate the wheat from the chaff, we use the signal provided by prestigious journals, prestigious universities, prestigious professorships, prestigious distinctions. The very cream of the top gets Nobel Prizes—one of the most prestigious honors in the world.

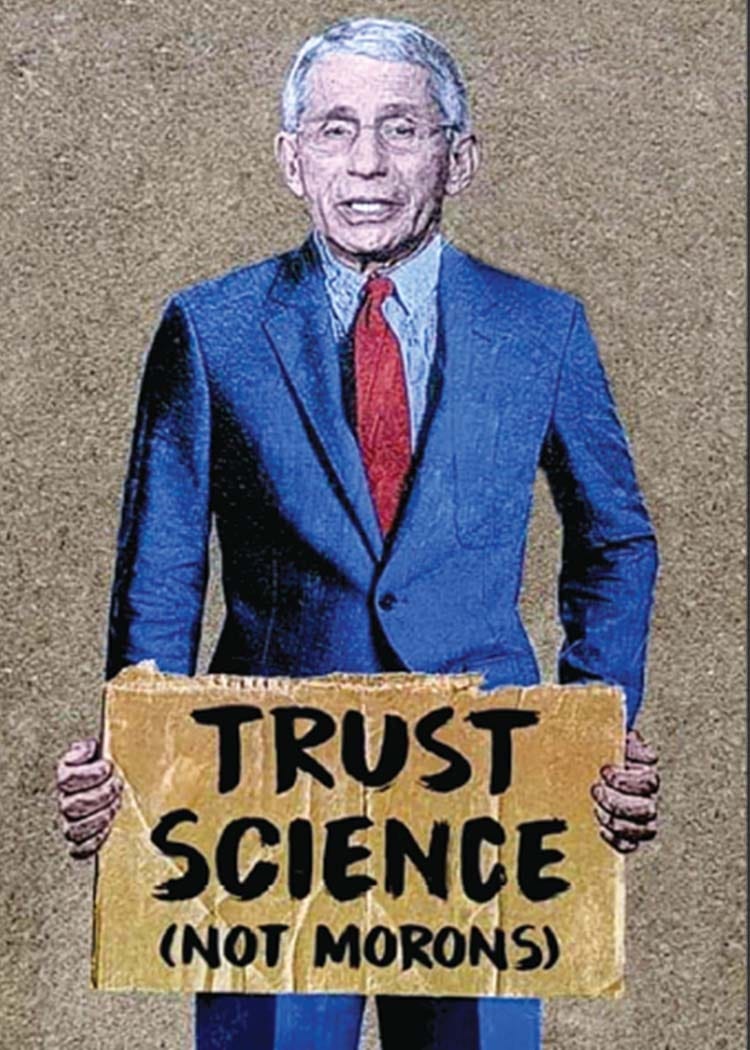

The importance of prestige in science causes some problems, but it also creates a positive image of science and scientists in the wider society. During the covid pandemic, there were lots of calls to “trust the science,” which I personally have a lot of problems with (science should fundamentally encourage the opposite of trust), but which may have help avoid the worst outcomes.

What if, by messing with journals or academia, we destroy the prestige structure and as a result harm the public status of science? That might mean fewer people giving to scientific causes, governments withdrawing funding because the electorate doesn’t care, fewer students picking science as a career, etc.

Science is less useful than we think

“We don’t put theories into practice. We create theories out of practice,” writes Nassim Taleb in Antifragile. According to him, pretty much all progress is due to engineers and tinkerers. Scientists come later and explain things, rather than provide the basis for new inventions to happen.

I don’t think that’s generally true, but it may be partially true, and if so, then the value of science may be lower than what we usually think—in which case fixing it is not a good use of our time and energy.

Science is dangerous and should be slowed down!

There’s actually a strong case for this in artificial intelligence. A superintelligent being could be very dangerous for humanity, and it’s worth making sure we have enough time to prepare before we unleash such a force. There is no guarantee that all progress in computer science will be beneficial to us.

And then there are less esoteric threats like viruses. It will probably never be known for sure whether SARS-CoV-2 came from a bat cave or a lab in China, but regardless, gain-of-function research has the potential to create and release dangerous pathogens. It’s good if this sort of research is severely restricted or, perhaps, actively discouraged.

In this view, things like the broken publishing process are good because they impede the progress of science. My feeling is that we still need quite a lot of progress—so many problems still need solutions!—but this is probably true for some field, and may become truer over time as we invent new potential ways to destroy ourselves.

This was a quickly written post because, well, I’ve been super busy with JAWWS and OADAO and The Classical Futurist and other things. But I’m glad I took the time to write it. It’s always worth considering, once in a while, that you’ve been looking at everything wrong.

With that said, I don’t think I’m wrong, so let’s now go back to trying to fix science!

I set up a nice shiny new Substack newsletter for it! Feel free to subscribe. I’m going to use it to send irregular updates about JAWWS.

Curtis Yarvin's take on "There is no science, only The Science" is key to understand why it is not fixable. Empirical research and peer review are inherently two different processes.