More Men Made of Miscellaneous Materials

Catalogue of useless anthropomorphized rhetorical devices 🤺

You already know the straw man: a rhetorical technique in which you take someone’s argument and make a weak version of it, as if made of straw. Someone says building denser neighborhoods is a good idea; you reply that they want to cover the world with ugly skyscrapers and leave no place for nature. This bad, new argument bears superficial resemblance to the original argument, like a straw man to a person — but it is easy to knock down, allowing you to score quick points in a debate. (Unless someone catches you, anyway.)

You may have heard of the steel man, the opposite of a straw man. Instead of weakening the argument, a steel man seeks to strengthen it. (“The most popular tourist destinations are dense neighborhoods, so yeah, we should build more of those!”) It is an ancient rationalist technique, a way to turn disagreements into something productive: by interpreting your opponent’s point charitably, you can both arrive at a better position faster. And if you do knock down the steel man in a fair fight, that means the argument was truly flawed.

A year ago I invented the gold man (or gold-plated man, as I called it then). It means crafting not a strong but an interesting version of the other’s argument. Often you don’t particularly need to win or to seek truth, and in that case the best thing to do is simply to keep the discussion going. Add a fun assumption; take the conversation somewhere new; say “yes, and” like in improv. People love visiting theme parks like Disney World; can we draw inspiration from them to build dense cities? It doesn’t matter if you believe that; what matters is that it is generative.

This three-way typology is useful. But why stop there? There are lots of kinds of arguments in the wild! Here are some obvious extensions.

A glass man involves transparently laying down all the assumptions made by an argument. Such direct access to the insides of the position can be useful and lead to much clarity, but unfortunately it also tends to make the argument brittle and fragile. A mere brush with it and it might tumble and break.

A diamond man is like a glass man except you manage to avoid making it weak in the process. It resists everything. This is very hard.

A pyrite man is when you think you’re making a gold man, but your interesting version of the argument turns out to be stupid and you merely manage to make a fool of yourself.

A particleboard man is the opposite of the gold man: a version of the argument so utterly boring that everyone involved spontaneously decides to leave and do something else with their day. (This can be a good thing.)

A rusty steel man is an old steel man, for example seen in a blog post from 2011. It was probably powerful and impenetrable back then, but the passage of time has corroded it. Now, with the new information available to us, everyone can easily see how flawed the argument is despite wearing what was, once, thick armor.

A stainless steel man is a steel man for which special pains have been taken to make it corrosion-resistant, for example by explicitly stating how future developments might affect the argument.

An nitrous oxide man is a joke based on your opponent’s argument.

An ice man is any version of an argument that you post online and then delete some time later, for any reason. When people try to refer to it after that, they find nothing but a puddle of melted water.

A polyethylene plastic man is a general-purpose argument that can readily adapt to the shape of any other argument. For example, you can almost always turn an argument into a statement about “human nature.” This initially sounds powerful, until you realize that the plastic man is an extremely cheap device, so generic that it basically never adds anything to the discussion.

To invoke a cactus man, read an argument, then take some hallucinogenic drugs, then think about the argument as you go on a psychedelic trip, then come back and make a new version of the argument inspired by what you saw. It will be surreal and totally obscure, full of spines to deter anyone from engaging with it. It won’t get you anywhere. But at least you got a hopefully interesting psychedelic trip out of it.

A lead man is made of metal, like a steel man, but the metal is subtly toxic. The man of lead may be able to defend itself in the debate arena, but it makes points that somehow make the debate worse or pollute the commons. It gives the appearance of epistemic clarity while actually creating resentment or entrenchment in each other’s position. This is what people worry about when they say they’re against steelmanning or that steelmanning is an especially insidious form of strawmanning.

A uranium man is slightly radioactive: it is a version of the argument to which you have added references to culture war topics. What those are depends on the time and place, but they often include things related to race, religion, gender, partisan politics, etc. The uranium man in itself can be harmless and useful, though onlookers may be wise to move away. Careless mishandling could cause a chain reaction and trigger a nuclear accident.

Or you could be deliberately careless and make a weapon-grade enriched uranium man, adding inflammatory or taboo elements on purpose to start your local equivalent of a nuclear war. This, it goes without saying, is not generally recommended.

A clay man, sometimes called a golem, is when your modified version of an argument inadvertently takes a life of its own. It becomes a meme, or even a psychocreature, and spreads throughout the layers of human culture. Hopefully it is aligned and has effects you agree with. You wouldn’t want your golem to accidentally create a religion and, centuries down the line, extremely bloody holy wars.

A paper man is a version of the argument that may well be great, but it requires so much background reading, helpfully provided by you in a plethora of links yet receiving no clicks from anybody, that it doesn’t actually advance the discussion in any way.

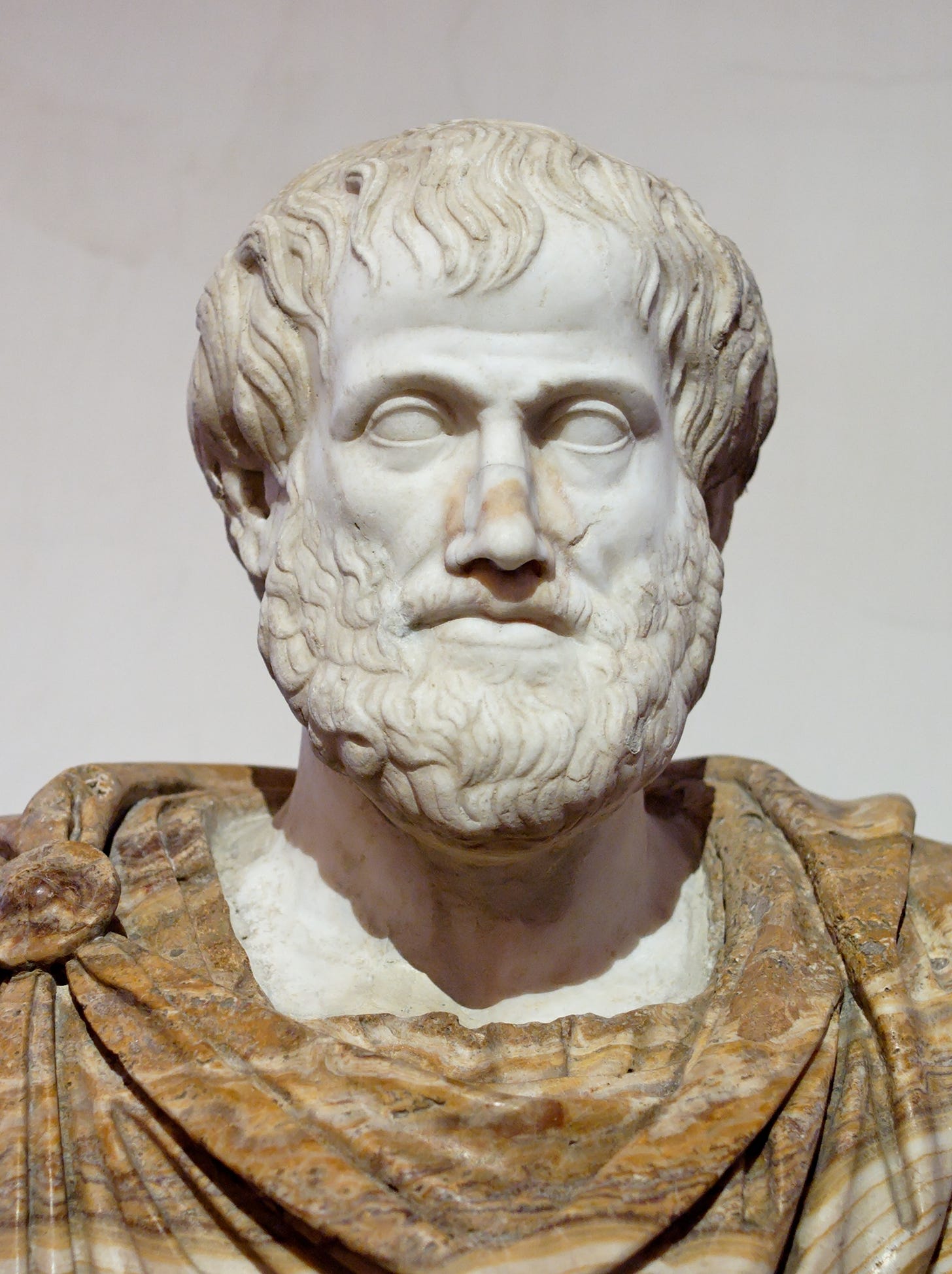

The related marble man casts the original argument into a classical mold, emphasizing that The Ancients have already made that point 2,500 years prior. The marble man has two uses: show that your opponent isn’t original, and display your own sophistication.

A wax man, like a statue in a museum, is a perfect word-for-word repetition of your opponent’s argument — except that you somehow manage to give it an uncanny air, as if to ascribe nefarious intentions to the person who first uttered it. A successful wax man doesn’t misrepresent the statement, but makes other think, “what kind of person would say such a thing?”

A gas man is a representation of an argument that is fuzzy, shapeless, impossible to understand. Very quickly it dissipates and nobody can say what you meant or even remember that you said something.

A dark matter man is an argument that everyone is pretty sure exists, and it would be great if someone actually made it, but nobody knows what it truly looks like.

An unobtainium man is when you turn the argument into something that’s so perfect along all dimensions that you immediately win the debate and turn your opponent into a lifelong friend. It is widely considered to not exist.

A helium man is when you repeat your opponent's argument in a funny voice to make fun of them.

I can think of another definition of ‘gas man’