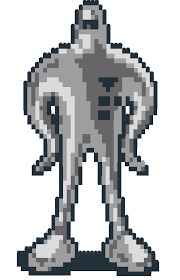

The Strawman, the Steelman, and the Gold-Plated Man

Turn other people's arguments into the most interesting version of themselves 🥇

A strawman is when you purposefully misrepresent someone’s argument. You create a weak version of it, made of straw, unable to defend itself — and then you defeat it. This is great for scoring rhetoric points in a debate.

Let’s use this Paul Graham tweet as an example:

A strawman of this, for instance, might be, “Paul Graham thinks that writers should never use an editor.” That would be a dumb argument, easily defeated. It’s also not what Paul Graham said. But if onlookers aren’t careful, they might see the fallen strawman on the battlefield and think you heroically killed him, thereby scoring a point against Paul Graham.

A steelman is when you purposefully make someone’s argument not weaker, but stronger. You interpret it in the most charitable way possible, perhaps beyond what you yourself believe. Obviously this won’t help you defeat an opponent in a debate; rather, the point is to figure out the truth. Instead of waiting for the other to defend their argument, you try to accelerate the process.

In our example, the steelman could be, “Paul Graham probably means that although editors often help, which is why the publishing industry relies on them, there are cases where the writer themselves can fulfill this purpose without needing external help.” Maybe that’s not exactly what Paul Graham meant. Maybe that’s not exactly what you believe. But it’s an interpretation that is both plausible and more defensible. You give the man an armor of steel, so that he is not easily killed — which means that if you do kill him, it is because he was truly flawed.

Steelmen are useful, but they’re not appropriate in all situations. More often, you’ll want to invoke a third, more complex type of man. Let’s call him the gold-plated man.1

The gold-plated man is, well, plated in gold. Gold is not the strongest metal, and accordingly the gold-plated man is not necessarily the strongest argument. Neither is gold obviously weak, like a man made of straw. There might still be steel under that gold plating! Instead, the point of gold is that it attracts attention. It is interesting. You don’t want to kill the gold-plated man; you want to admire his armor and hear what he has to say.

In less metaphorical terms, what I mean is that it’s useful to assume the most interesting interpretation of whatever other people say. Just like in improv, you should pretend that your discussion partner is a genius (whether they actually are one or not), and that they made a really original, subtle, clever point. Pretend that their argument comes dressed in gold.

For example, you could interpret the Paul Graham tweet like this: “Editors appear superficially helpful, but with the most talented writers, they tend to remove the life from the writing and make it less unique.” I’m not sure whether Paul Graham really thinks that. Nor is it necessarily something I’ll readily agree with. But it’s generative. It’s more interesting than the previous two examples, neither of which really invited further discussion.

There are occasional situations where scoring easy rhetorical points against a strawman is appropriate, and there are situations where assuming a charitable steelman interpretation is an opportune way to arrive to the truth. But most conversations really only need to be interesting. They just need to somehow keep going. Turn them into beautiful, dazzling shows, starring knights clad in golden armor, and the truth will emerge in due time, simply because there will be more time.

People sometimes use strawman and steelman as verbs, as in “strawmanning” or “steelmanning” something. For the gold-plated man, we’ll get rid of the awkward participle in the middle and say “goldmanning.”

This has most certainly happened for probably all twentieth-century art, especially abstract art.