On the Proper Use of the Moon

AWM #54: Astronomical errors, artistic license, and why you should care about getting the night sky right 🌙

It was barely past midnight when she got up after two hours of pretending to sleep. From the snoring in the next room, she knew her father and his fiancée wouldn’t wake up anytime soon. She would already be far away when they realized her absence in the morning.

She opened the bedroom window, felt a waft of cool air on her face. With careful gestures, she took off the window’s bug screen. Then she grabbed her backpack. Everything was ready: food, money, clothes. She jumped out of the window and landed in her stepmother’s tasteless flower beds. No harm in trampling those a little. She began walking in the backyard under a crisp, clear sky. The stars were shining despite the glow of the city, and a butter-colored full moon was just rising above the eastern horizon. A perfect night for her escape.

There’s a mistake in the above story. Did you notice it?

It’s rather subtle, so I’ll tell you. The story is set “barely past midnight.” But the full moon is “just rising above the eastern horizon.” This is literally impossible. The full moon never rises around midnight.

Really? Really.

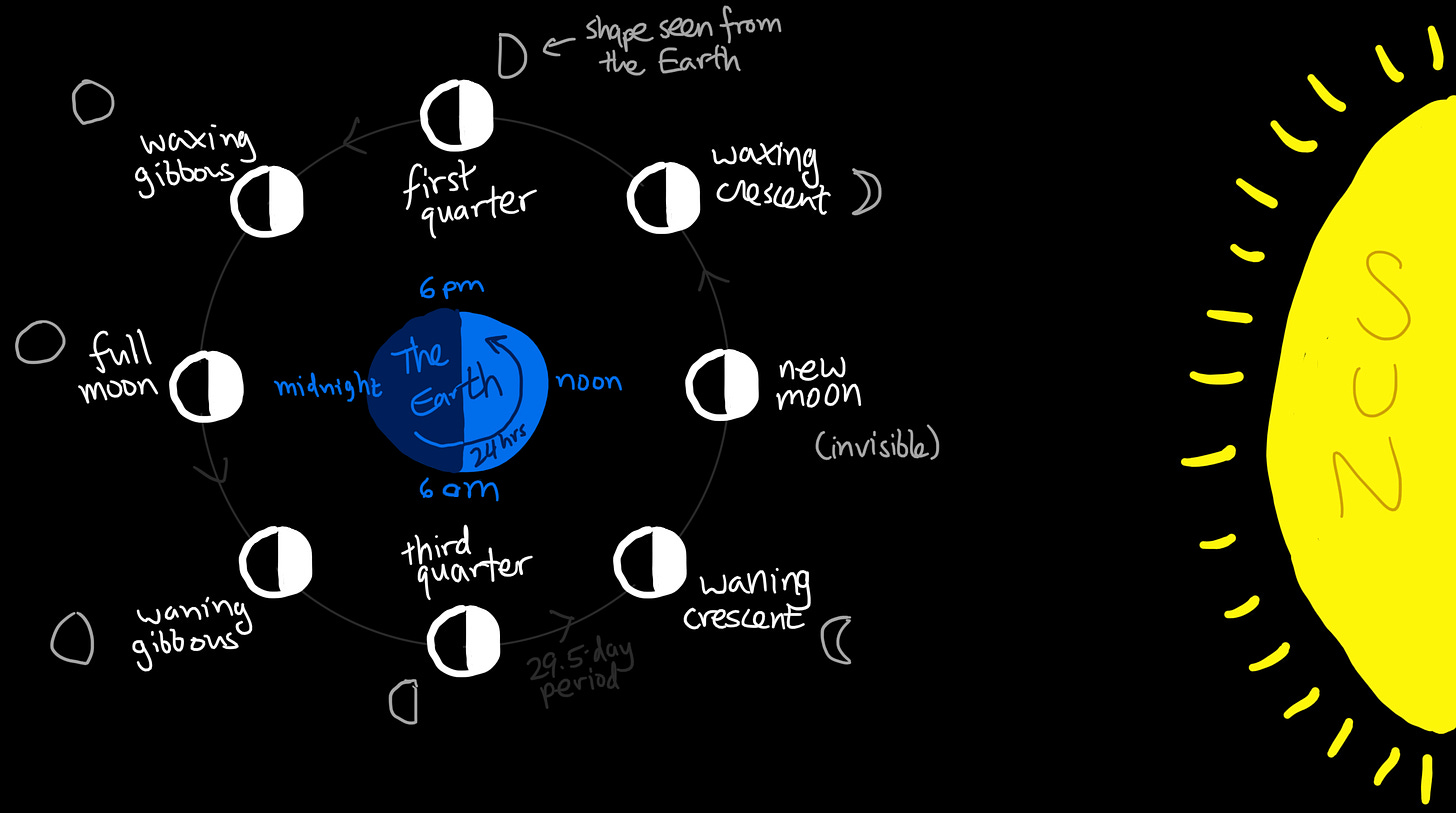

It’s easy to understand if we think about what a “full moon” means. The sun always casts light on exactly half of the moon (with the twice-a-year exception of lunar eclipses), so a full moon means that we see the entire sunlit half. For this to happen, the moon has to be positioned on the side of the Earth that is away from the sun.

“The side of the Earth that is away from the sun” is better known under another name: night. The full moon becomes visible (it “rises”) when the night begins, i.e. when your location on the rotating Earth moves from the sunlit to the dark side of the planet, around 6pm. The moon becomes invisible (it “sets”) when the night ends, i.e. when you go back to the sunlit side, around 6am. At midnight, the full moon should be as high in the sky as it gets.1

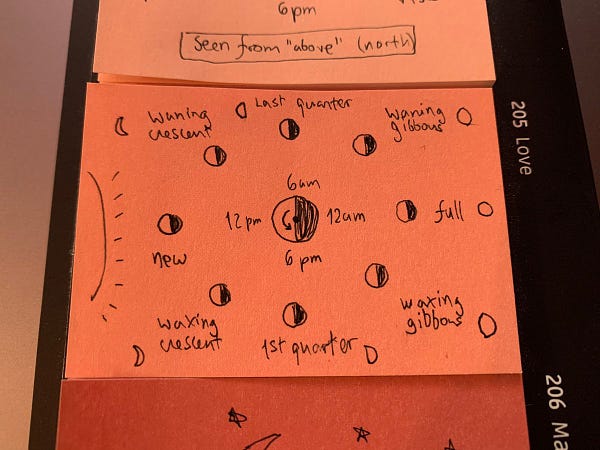

This is only true of the full moon. The other moon phases mean different positions of the moon around the Earth, such that we see a smaller fraction of the sunlit half. Take the last (a.k.a. third) quarter. It occurs when the moon is above the part of the Earth that is experiencing sunrise. So it will rise around midnight, reach its highest point in the sky in the morning, and set around noon. A last quarter is what our runaway teenage girl should have seen rising above the eastern horizon.

If you want a cheat sheet for all the moon phases, you can refer to this tweet of mine:

The full thread highlights other mistakes that we make about the moon in art and fiction.2

One of them is putting the moon at a random spot in the sky. In fact it must be on the same line that the sun and planets follow: the ecliptic. (It’s also the line that goes through the 12 zodiac constellations.) This is because the moon is in the same plane as the rest of the solar system.

Another mistake is lighting the wrong side of the moon, relative to the sun. If you draw a sunset with a moon crescent in a corner of the sky, make sure the lit part of the moon is not facing away from the setting sun!

An even more common mistake is having the sun cast light on more than half of the moon, like this:

Or this:

For the moon to look like this, it would have to be lit from multiple directions. Again, this never happens! The only situation in which a dramatic crescent like this can be seen is a solar eclipse — and it happens to the sun, not to the moon.

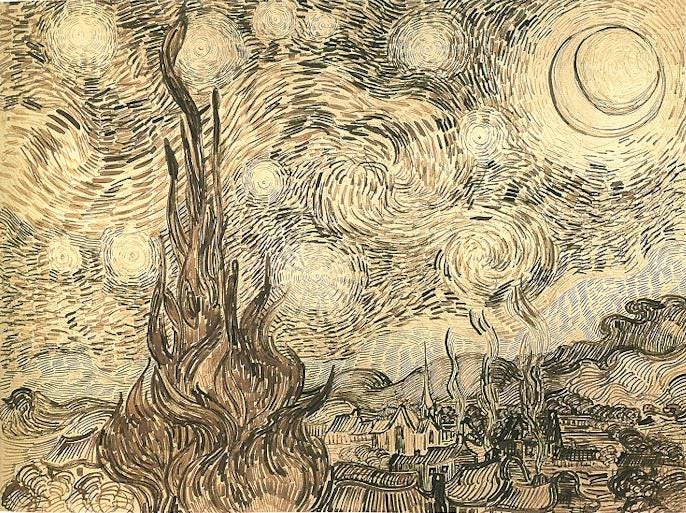

At this point some may be tempted to say: Come on, allow those artists some freedom! Nobody cares that the moon is not 100% scientifically correct in all paintings and stories! Are you really chastising Vincent Van f*cking Gogh for not getting the moon right?

No, I am not chastising Vincent Van Gogh. Vincent Van Gogh can do whatever he wants, because he’s Vincent Van f*cking Gogh. He’s an artist, and artists get artistic license. They’re allowed to deviate from reality.

But — and this is the main point I want to make — there is a difference between using artistic license and making mistakes. The difference lies in awareness and purpose.

Van Gogh knew that he wasn’t being realistic. He painted The Starry Night when the moon was gibbous, and he was apparently going to make the moon gibbous in his picture too. But then he decided to switch to the crescent shape, probably because it was more symbolic. He was doing it on purpose. It wasn’t a mistake born of ignorance.

Looking at the other examples, the picture with the birds is definitely not trying to be astronomically correct, so whatever. The picture of the sunset in the desert, however, seems to be imitating photography, and it would have been easy to rotate the crescent moon so that it faces the sunset’s glow. So I’m guessing it’s a mistake rather than a carefully considered artistic decision.

As for my fake story at the top, it’s a mistake I made on purpose for this essay — but it’s a realistic mistake! The butter-colored full moon is just an atmospheric detail, meant to paint a picture in the mind of the reader rather than play a concrete role in the story. A full moon, just rising, is more dramatic (“it’s a metaphor for the beginning of the protagonist’s quest,” a literature class dissertation might say) than a third quarter or a completely risen full moon would be. So a writer might write that without taking the time to consider whether full moons actually rise at midnight.

The source of these mistakes is pretty obvious. The moon is a powerful symbol for the idea of night. It’s the most visible thing in the night sky, whereas it is overshadowed (or, rather, outshined) by the sun during the day. Night doesn’t have any other good symbols — stars are too small, numerous, and symbolic of other things to work well. Plus, the moon provides an elegant balance for the sun when symbolically contrasting day and night. So the night/moon association is tight in everyone’s mind, even though the moon spends exactly half its time in the day sky.3

At the same time, people generally have a rather fragmentary grasp of astronomy. Maybe because it’s a little too complicated. Maybe because most of us live in cities with a lot of light pollution. Maybe because it just isn’t very useful to our daily lives.

The result is that symbolic representations of the night sky are much more readily available to us, when making art or fiction, than the real night sky is. We use the autocomplete of our minds instead of going out at night in the countryside to look at the sky. And the autocomplete of our minds usually suggests “🌙 “ to go with “night.”

Artistic license is all about not blindly following the autocomplete.

However, no one is preventing you from using the autocomplete suggestion anyway, if it creates a cool effect. It’s purposeful. And a clear purpose makes good art.

This is the reasoning behind the well-known quote “learn the rules so you can break them” (which I have seen attributed to both Pablo Picasso and the Dalai Lama). If you break a rule that you weren’t aware of, it’s a mistake; if you break a rule that you knew about, it’s artistic license.

You would think that artistic license and mistakes are indistinguishable. Sometimes they are; sometimes a mistake turns out to be artistically interesting. But somehow, it almost always shows when the artist or writer doesn’t know what they’re doing. It shows when they aren’t paying attention to the small details. Self-awareness and purpose can’t be faked.

So do whatever you want with the moon, but try to do it purposefully. There are mistakes that you can easily avoid. Now you know.

Note that all times are approximate due to how time zones work, plus daylight savings, which creates a 1-hour discrepancy with astronomical time. Also, the actual time of the beginning of the night depends on your latitude and, because the Earth’s axis is slanted, on the season. For our purposes, let’s simplify all that and say the night begins at 6pm.

Slightly less than half if you don’t count the new moon, which is in the sky from 6am to 6pm, but is invisible.

Was the story set in contemporary China? There everyone uses Beijing time so the clock may say midnight when astronomically it’s 8PM if you are as far west as you can get. Tibet is mountainous so with some help from a nearby peak we might manage to have the moon ‘rising’ while being full and the clock showing midnight.