Please plagiarize this blog post. I mean it, literally.1 Open a Google Doc, or Word document, or your existing Substack editor (create a new publication if you like) and then copy this blog post into it. You can even hit publish, if you want, under your own name. You have my full permission, as long as you follow two simple rules.

The first rule is that you must link back to the original source, which you can do by copying this very sentence, with the URL, https://etiennefd.substack.com/p/please-plagiarize-this-blog-post. The other rule is that you have to copy the post word by word. No copy-pasting allowed.

Why would you do such a thing?

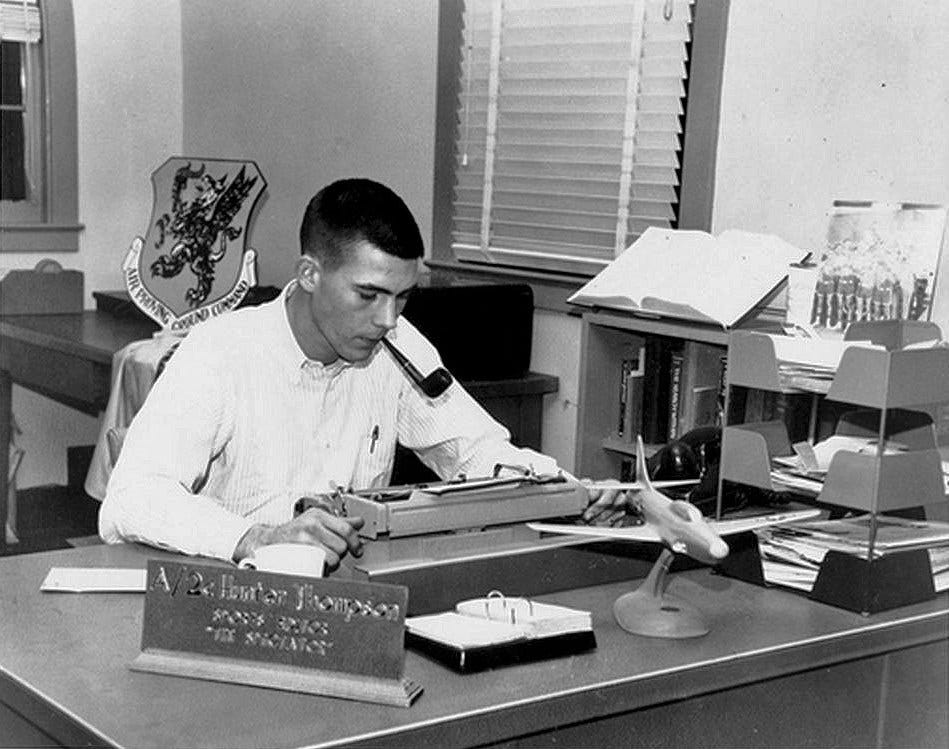

It is said that the great American writer Hunter S. Thompson once typed out parts of Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, because he wanted to know what it felt like to write a great novel. (He did this at work while employed at the magazine Time in 1959. The magazine Time eventually fired him.) We can only speculate on what, exactly, Thompson learned from the experience, but we at least know that he would go on to write famous books such as Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. That seems like a good sign, survivorship bias aside.

Occasionally, one hears anecdotal reports of other writers doing a similar exercise. The author of this post has done it, as preparation, on about half of Book Review: Arabian Nights, by Scott Alexander, and he found the experience both useful and interesting. It even made him begin reading the actual Arabian Nights yesterday.

So, assuming you want to write — and if that assumption doesn’t hold, we’ll discuss other kinds of work shortly — then you could do worst than copy a great blog post. Of course, it would be presumptuous to say that this is a great blog post. You should feel free to go and type out, word by word, your favorite blog post, whatever that is, though it’s probably safe to assume you won’t have permission to publish it in that case. You could also copy a short story, or part of a book, or whatever you like. If you don’t know what to copy, and you need any random idea, then this blog post could be it.

The first thing you’ll learn from typing out someone else’s work is just how much you’re usually not paying attention. If you pick a piece you really like, that probably means you’ve already given it a number of reads. And yet, when you set out to copy the first few sentences, you may very well notice details that you had missed each time.2 Writing it out forces you to pay attention, at least a little bit, to every letter, to every word.3 When we read normally, we don’t do that; we read sentences, whose meanings we grasp without consciously registering each symbol we see.

Some of the details you notice will be mistakes. In a great work, obvious mistakes are usually absent, simply because otherwise you wouldn’t call it a great work. But subtle mistakes abound. These include dumb but hard-to-notice typos, misplaced punctuation signs, inconsistent use of italics, and errors of style (an inelegant repetition, a rhythm that doesn’t quite work, a sentence that is too heavy for its own good).

Noticing these mistakes is useful for two reasons. The first reason is that you may become better at avoiding the same mistakes in your own writing, or at least at spotting them. The second reason is that it will fix your impression that the great work you’re copying is perfect. Professional orchestra musicians strike false notes all the time, and so do great writers. Once you realize that, writing gets less scary. But since we don’t usually pay enough attention to spot the subtle mistakes, and the egregious mistakes are usually filtered out before the writing reaches you, it takes some effort to get there.

You’ll also notice other cool details that aren’t mistakes. Elegant repetitions, rhythms that are almost like music, sentences whose construction, when you stop and think about it, is masterful. You’ll notice words that you’ve never though of using, until now, whose meanings you sort of guessed, but now, having typed them, you understand well. You’ll notice the ways the author adds microhumor and make you smile as you read along.

Noticing the good stuff is useful for obvious reasons, and again it takes some effort. In theory you can do that through simple reading, if you manage to pay close attention. In practice that rarely works. You need a forcing function. Copying is one.

Paying close attention allows you to see the small details, but it also has beneficial effects at the level of the entire piece of writing. After copying a blog post, you’ll almost certainly remember it well enough to talk about it without effort. If the post contains important arguments, that’s a way to get better at conversation on the relevant topic. If it contains beautiful passages, you’ll now be able to recall them at any point for quoting purposes.

You will also absorb the overall style of the piece. It will rub off on you. Which is great, if you’d like to write in a style that you do not quite master. If you want to be funny, or solemn, or ironic, first copy a bit of writing that is in that mood, and whatever you write next will carry some of the same quality.

Copying gives you practice, at a low cost. Of course, the practice doesn’t quite cover the full gamut of writing skills: you’re not practicing idea generation, or finding the right words to express a complicated idea. When copying, these are given for you. But this is precisely why such exercising comes at a low cost: since you’re not doing the hard, creative parts of writing, then it’s far easier to practice the basic parts, like just sitting in front of your laptop and type reasonably quickly. You can’t just practice sitting in front a laptop and type quickly, if you want to become a great writer, but you do need to be able to do that. So basic practice can be valuable. If you only ever try to practice the full package, but recoil because finding good ideas is hard, and as a result never even get good at sitting in front of your laptop and typing quickly, then you won’t be getting anywhere.

Because copying is low stakes and easy, it’s also a good way to get into the groove. You blocked off an hour to write, but you’re facing the blank page? Just copy a couple paragraphs from a blog post you like, and before you know it you’ll be inspired to write the post of your own you wanted to work on in the first place.

As you copy something, you might start wanting to make changes to the original material. Go for it. The point isn’t to religiously copy something; you’re not a monk in a scriptorium. The changes you make will be a learning experience, too. If you change enough stuff, perhaps you can even claim the result as your own.4

We’ve been discussing writing, primarily because it is the creative genre the author knows best — but also because it seems that we rarely blatantly copy written works, for some reason. Perhaps because copy-pasting is so trivially easy, so doing what Thompson did in the 1950s feels totally pointless now.

But copying is a much stronger tradition in other art forms. In music and theater it is extremely normal: they are performance arts, where each performance is an imperfect copy of previous performances, all harking back to the Platonic ideal of the original composition or play. Connoisseurs take pleasure in noticing the minute differences between the copies. Sometimes performers try to innovate by altering an aspect or another of a new copy, while keeping the core intact.

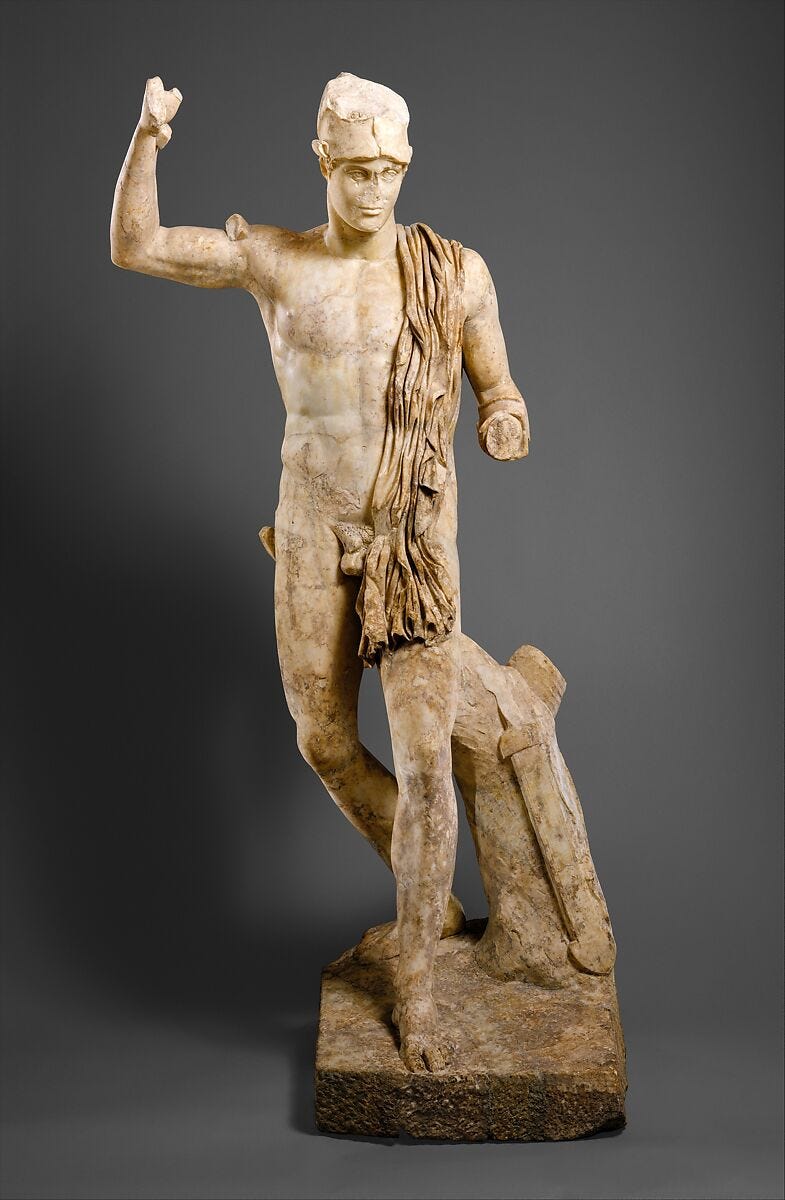

In the visual arts, copying is also reasonably common, though of course trying to sell your own version of someone else’s art would usually be frowned upon. Before mechanical reproduction was widespread, artists would reproduce statues and paintings because there was no other way for a rich person to get their own version of a well-loved artwork.

And then, of course, there is art forgery, a fascinating phenomenon because it is both dishonest and highly impressive: to make a credible forgery is to be an extremely skilled copyist. There are also stories like the Mytens–van Dyck rivalry at the court of Charles I of England, where Anthony van Dyck demonstrated his superior skill over Daniel Mytens by reproducing the painting at the top of this post.

All of these examples of copying are, presumably, great ways to learn the craft. That hasn’t changed. I’m not sure to what extent aspiring artists spend time reproducing works they admire, but I’m guessing that they do it a fair amount. It’s just less immediately rewarding than it once was.5

In complex art forms such as movies or games, perfect copying seems to virtually not exist, probably because it would be too expensive. At most we get remakes, which are both copies and explicitly not: they’re supposed to improve on the original in some way, otherwise we wouldn’t make them. Maybe some of the sub-disciplines of moviemaking or game design, like editing, have their copyist enthusiasts.

For the reasons enumerated above, it is probably worthwhile to try and copy an existing work perfectly, no matter what your genre is. But if you feel like you must justify the exercise, and provide some useful service, there are ways to do that.

One is to provide commentary. As you type out the blog post, write down your thoughts whenever they occur. If they’re interesting enough, as they almost certainly will be, you can publish an annotated version of the original post, or a review post, or some other way of building upon the work. The original author, if they’re around, will probably be pleased rather than irritated.

Another way, if you know multiple languages, is to translate. This is extremely close to copying, and yet distinct enough, that you’ll get the advantages both of paying close attention and of creating something valuable for others. The original author of what you translate will typically be quite pleased that their work is now accessible to a wider share of the world. Of course, the downside is that translating is hard work. But it can be a lot of fun.

Relatedly, copying word by word a text in a language you know poorly seems like it could be a great way to get better at the language, though this is only speculation on my part; I haven’t tried it.

You could also “translate” in ways that have nothing to do with languages. Vary the tone, the word choices, the visual layout, turn a blog post into a short story, or into a movie script. Rewrite a blog post in an overwrought Victorian style, just for fun. Make it into a physical book with beautiful typography. Play with the material in any way you like.

No matter how you do it, if you’re going to be public about it, acknowledge the extent of your copying. Artistic duplication gets a bad rep because of the times it is done dishonestly, like art forgery or (actual) plagiarism. Doing it in the open, while referencing the original source, makes everyone far happier. Alternatively, do your copying fully in private, without ever telling anyone.

If you’re actually plagiarizing (or translating, or adapting) this blog post, then you’re getting at the end. Congratulations! I hope the experience was worthwhile. If you’re just reading, then that’s great too — your attention is a precious resource, and I’m happy you chose to spend it here. Now go and copy something else, if you want.

Well, except in the sense that plagiarizing usually implies absence of consent.

The third sentence of Book Review: Arabian Nights is “[One Thousand And One Nights is a]bout how to use indexical uncertainty to hack the simulation running the universe to return the outcome you want.” Which is both a great sentence and one I had never consciously noticed after reading the post 2 or 3 times.

If you notice you’re copying mindlessly, without really noticing the words, stop and take a break. Otherwise you’re truly wasting your time.

You have full permission to write and publish an altered version of this post, too, for whatever level of alteration you desire, although please don’t attribute it to me if you change it a lot.

Perhaps the same is true of books. I wonder if the monks who copied works in a scriptorium all day, before the printing press, were among the most learned people to have ever lived.

Well, you asked so very politely, I simply couldn't refuse: https://consistentlyinconsistent.substack.com/p/please-plagiarize-this-blog-post

Étienne, I love this post. In one of my lower-level college writing courses, one of the options we had was to rework an essay by mimicking an author's work in grammar and tone, but using our own topic. The pronouns, verbs, conjunctions, etc were all in the same syntax as the author, but we did not directly use the words themselves. It was in effort to help us understand tone, style, etc.

To this day, when I find a group of sentences I really enjoy from an author, I copy it word-for-word, then choose a different topic to mimic the author - and then I edit it to be in my style/tone. It's incredibly time-consuming but I absolutely love doing it. It encourages me to adopt a tone or style I would not have necessarily done otherwise.

When you mentioned, "But copying is a much stronger tradition in other art forms...." I immediately thought of my piano lessons growing up. As a kid, I often thought, "all these songs sound the same!" I can't always distinguish each composer now, but the fact that art builds upon itself (ie Mozart being directly influenced by Haydn) makes for better art long-term - and I no longer think all those pieces sound exactly the same.

Love this piece. Thanks for sharing it, Étienne.