This is the 50th post on this newsletter — half of my goal of 100! It’s also the 10th post since I started the Rabbit Hole theme. I would celebrate if I weren’t stuck in an isolation hotel in New York City because the covid test I got for my flight back to Montreal returned a positive result. Oh well.

Before you ask, yes, I’m totally fine. In fact, surprisingly, my mood has been great. Maybe better than it’s been throughout the entire pandemic. Possibly it is a lingering effect of getting so much Texas sunlight this past month. Or simply the fact that I really needed to travel abroad to get rid of the negative emotions associated with my home. (Of course now that I’m stuck here I just really want to go home.)

Maybe it’s also the almost stress-free experience of getting covid after everybody else. Now I get to see what the beast is like. And as a vaccinated person, it’s less “sneaky apex predator” and more “small cat trying to look ferocious but just managing to look cute.” The symptoms are on par with a mild cold: a runny nose, an occasional cough, some tiredness. They’re also almost gone now, after a week.

Well, with one exception: the lack of a sense of smell. That one’s unique, and still present. But then it’s also a unique experience, so it’s kinda fun in its own weird way.

Smellin’ nothin’

Loss of vision is called blindness. Loss of hearing is called deafness. Loss of touch doesn’t make a whole lot of sense (pun unintended) because “touch” is a bunch of senses like temperature and proprioception that are bundled together, but losing these senses can happen and the general condition is called somatosensory loss. Loss of taste is called ageusia. Loss of the sense of smell is called anosmia.

Pretty much every source about anosmia will tell you that it sucks more than you would expect. We don’t expect it to suck that much because the sense of smell, in humans, is rarely seen as something of much import. But it sucks more than that because smell affects us in a myriad ways we don’t consciously think about. Knowing whether things (clothes, our own bodies) are clean. Detecting signs of danger like poison or smoke. Being attracted to other people.

And the main one: food and drink.

As you probably know, the tongue is considered to only distinguish between five types of substances:

sweet (sugars and things that mimic sugars)

sour/acid (hydrogen ions H+)

salty (sodium ions Na+, and ions of other alkali metals like potassium K+)

bitter (several compounds with specific chemical properties)

umami (glutamate, including MSG)

The truth is more complex,1 but overall the sense of taste is rather limited. The vast majority of the sensations we get when we eat come from the thousands of molecules that olfaction can detect.

I fortunately do not have ageusia, so I can still taste sugar and salt. I also still feel the texture of food. But everything I eat feels blander now. Some things aren’t that affected: orange juice, whose flavor comes mostly from the sweetness and acidity, or tomatoes, which are mostly umami. Some others basically taste pefectly neutral now. This includes toothpaste — mint “taste” is 100% olfactory — and tea.2 Coffee is an interesting case: I can taste its slight acidity and bitterness, as well as feel the fattiness of the milk I add, but all the interesting flavors of a good cup of coffee are gone.

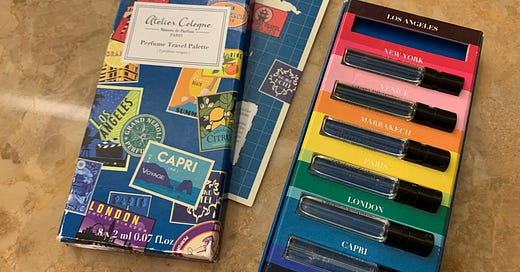

Starting yesterday, about four days after the onset of anosmia, I believe some of my sense of smell is coming back. Very little. I’m travelling with this lovely Perfume Travel Palette:

If I spray some and immediately try to smell it, I can detect that a smell exists, which I couldn’t do two days ago. But I can’t recognize anything about the smell. A visual analogy would be closing your eyes and then turning on the lights. You would notice the presence of light, but not any colors or shapes.

At the same time, food has become slightly more enjoyable. The flavors feel “fuller” now even if they’re not quite recognizable. I would say that my sense of smell has recovered to about 1% of what it used to be. This is already much better than 0%!

My experience so far matches that of Sasha Chapin. The next step, if I follow what he did, is to get a psychedelic drug like LSD to get the 99% that’s missing:

it totally worked. Fully and near-instantaneously. Like a light switch turning on. . . . LSD was essentially a miracle cure for my anosmia.

Intriguing. Scott Alexander was also intrigued, and wrote a really interesting post about what Sasha’s experience would imply. It includes a fascinating discussion of “state fixation disorders” such as chronic pain, where, plausibly, your brain reinterprets some temporary situation (a back injury, or a dysfunction of the olfactory organ) as a normal stimulus, and then you get chronic back pain or anosmia forever. Or, rather, until you slowly relearn to expect normality (no pain signals, normal smells), or quickly relearn that thanks to a psychedelic drug that makes your brain more plastic.

Maybe I should try, although I’m a bit scared of psychedelics (or any drug really).

Why does covid cause anosmia?

Regardless of whether and how LSD might miraculously cure anosmia, the other interesting question we haven’t asked yet is: why the hell does covid cause that?

Most other viral infections don’t. The closest they come to is blocking your nasal cavity with mucus, but that doesn’t count. My current anosmia is occurring even though my nasal passages are completely clear.

To understand this, we need to understand the basics of the olfactory system in humans.

Air comes into the nasal cavity, either from the outside or from the mouth. Then the odorous molecules it contains get caught into the mucus on the surface of the olfactory epithelium. Within the mucus are the terminal ends of some nerve cells, the olfactory receptor neurons. These neurons detect the chemicals in the mucus and transmit the sensation to other neurons on the other side of the bone, in the olfactory bulb, at which point we’re in the brain. Then some further processing is done to interpret the data and bring it to your consciousness.

The air might contain something less fun than odorous molecules. It might contain some SARS-CoV-2 virions. To infect a cell, a virus has to find a way to cross the cellular membrane. SARS-CoV-2 does this through ACE2, which stands for “angiotensin-converting enzyme 2.” ACE2 is one of the many things found in the membrane of cells.

But not all cells have ACE2. Notably, the olfactory receptor neurons don’t. So covid cannot actually infect and injure them, at least not directly. However, ACE2 is found in cells that support the neurons. These are “the sustentacular cells, which wrap around sensory neurons and are thought to provide structural and metabolic support, and basal cells, which act as stem cells that regenerate the olfactory epithelium after damage.”3 I think those cells would be the red ones in the (simplified) diagram above.

So it seems that covid damages the nasal epithelium, but not the neurons directly. That’s a relief — my understanding is that recovering anosmia would take longer if the neurons themselves had been destroyed. (Non-covid-related anosmia is often caused by damage to the neurons, including from traumatic head injury.)

My quick research didn’t lead to more detail than that. Why does damage to the supporting cells make the neurons stop working, exactly? Unclear. But at least it offers a path forward: my anosmia will be cured when the sustentacular and basal cells have regenerated. At least, assuming some weird state fixation thing doesn’t mess things up.

Meanwhile I’ll keep eating textured food and testing perfumes on me without having any idea what I smell like to others. At least those others are basically only the nurses and hotel staff. I suppose they got used to patients smelling weird: up to 80-90% of covid patients might suffer from anosmia. Fortunately, we almost pretty much all recover eventually.

There may be taste receptors to detect fat and calcium and other things; we still don’t know perfectly how taste works. Also the tongue is a touch organ that detects non-taste stimuli such as temperature and texture. Also non-gustatory nerves can be activated by certain substances (e.g. capsaicin in peppers), providing other sensations (e.g. spiciness).

I first noticed my anosmia last Friday, right after I received news of my positive test, when my friend brewed me a cup of lavender Earl Grey that tasted like plain hot water.

From this article.