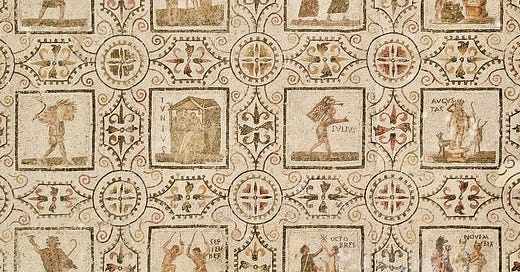

In the legendary era before they constituted their city into a Republic, the Romans are thought to have used a ten-month calendar. The first month was called the Month of Mars, Mensis Martius, in English known as March; the last one was Month #10, Mensis December. After December the year was not yet over, though: only 304 days had elapsed. The remaining 61 or 62 days of the solar year were spent in a monthless period, a blob of unmeasured time, perhaps less important because it was winter and agriculture was taking a break.

I repeat that this is legendary: there is little direct evidence of what is known as “Romulus’s calendar” (Romulus himself being a legendary figure). Already, by the time of the Roman Republic, January and February make an appearance.

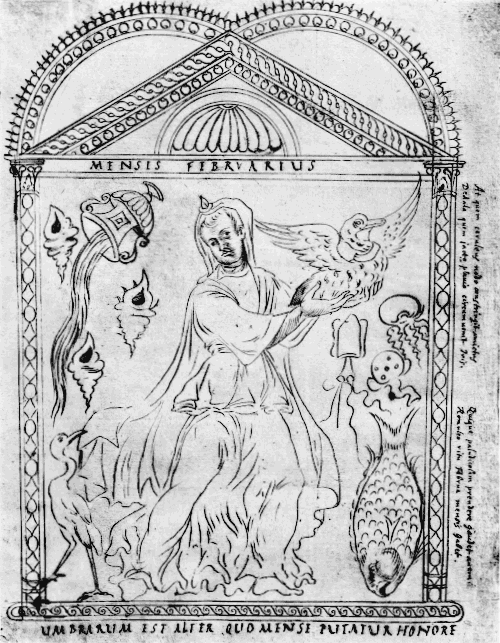

The Republican Calendar was still quite different from our modern calendar. Most months had either 31 or 29 days, to minimize the superstitious misfortune associated with even numbers. But February, that weird, unlucky month added at the end of winter, had either 28 days (on common years) or 23 days (on leap years). Those leap years were supposed to occur every two or three years, and they included an extra month, Mercedonius or Intercalaris, consisting of 27 or 28 days, right after February 23rd. This made leap years significantly longer than common years, at 377 or 378 days compared to 355. Over time the system was supposed to self-correct and align with the solar year of 365 ¼ days. Unfortunately, the decision of declaring a leap year or not became political. It was up to the top religious authority of the Republic, the pontifex maximus; and to the surprise of literally nobody, it became common for a pontifex maximus to use that power to his advantage, for example to shorten the office terms of political enemies or lengthen those of allies — with the result that dates became difficult to predict and plan around, especially if you lived far from the city of Rome and its incessant political intrigue.

It was a mess. Then came along Julius Caesar, who, as pontifex maximus himself, would reform this mess. The Julian calendar is (almost) what we still use today. It contains a small remnant of the intercalary month of yore: February 29th, a phantom day that materializes only once every four years, a day more unique and special than January 1st or December 25th, just due to a quirk of how our solar system works.

There would be only one more reform of the calendar, by Pope Gregory XIII, in 1582. A small tweak to February 29th, to make it vanish once more per century, three centuries out of four — because the solar year is in fact 365.2425 days, not 365.25. After this, no reforms at all.

Despite being much simpler than the calendars of Romulus or of the Roman Republic, the Gregorian calendar is still pretty quirky. The month lengths follow an irregular pattern, requiring cute mnemonics like that trick with hand knuckles to remember them. Our seasons and quarters have slightly different lengths as a result. Month names are all over the place: gods we don’t believe in anymore (Janus, Mars, Junon); quasi-forgotten festivals (the Februa, meaning “purification”); long-dead statesmen with uncertain moral legacies (Julius, Augustus); and numbers that aren’t even those months’ numbers (October screams, “I’m month #8! I swear! Octopuses have eight tentacles, not ten, don’t they?”). And then there’s the fact that a particular date falls on a different day of the week every year, due to the 7-day week (another relic of deep antiquity) not aligning with either months or years, in a pattern that is in theory easily predictable but in practice repeatedly gets thrown off a bit by the quadrennial return of February the 29th.

(If we didn’t already have such a weird calendar, and an author introduced one into a work of fiction, we would dismiss it as unrealistic.)

Besides, now that the West has culturally conquered almost the whole world, everyone uses the Gregorian calendar, with only rare exceptions, mostly for traditional or religious reasons.1 A calendar devised in ancient Italy (and slightly revised in early modern Italy) doesn’t exactly feel universal and multicultural.

There have been proposals to change this. In the 1950s, the United Nations came close to officially recommending something new: the World Calendar, a calendar that would be identical year after year. It always started on Sunday, January 1st, and always ended on Saturday, December 30th, followed by a special “Worldsday” — a single day outside any month, not unlike the monthless winter of the early Romans, to allow the next year to start on a Sunday, January 1st again. Leap years would have another extra day between June and July.

Interestingly, it is those monthless periods, short though they were, that defeated the proposal. As the countries were discussing whether to jointly adopt the new calendar, religious groups objected that their traditions required rites to be performed every seven days, and the extra Worldsday and Leapday would throw everything off by creating occasional 8-day weeks. In large part due to this, the United States government declined to support the World Calendar, and without US support the World Calendar was soon forgotten.

It seems that we must forever deal with the week-year mismatch one way or another, at least as long as there are significant numbers of Jews, Christians, and Muslims in the world.

It is not surprising that the last significant effort to reform the calendar was in the 1950s — that was the golden age of high modernism, a time when humanity had great trust in its ability to rationalize everything, from city plans to architecture to economies. It is also not surprising the the previous time a major reform of the calendar almost succeeded was during the previous period of great trust in humanity’s science and reason: the Enlightenment, and more specifically its terrible coda (in all senses of terrible) — the French Revolution.

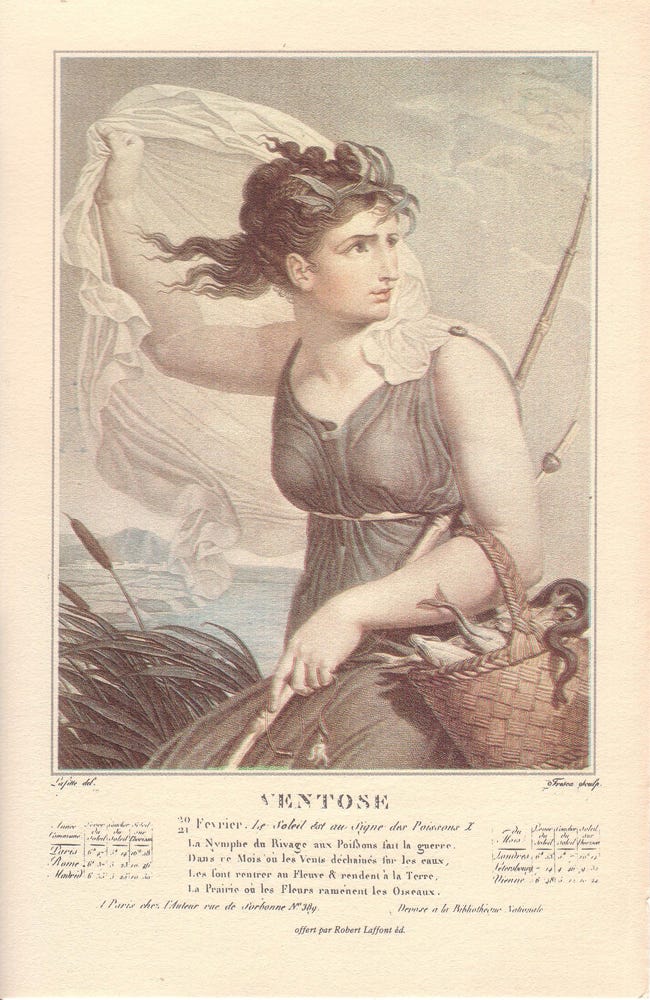

I’ve been a fan of the the French Republican Calendar ever since I learned about it. Such a utopian effort! Such a deliberate, ballsy insult to tradition and religion! The calendar sought to get rid of all pagan and Christian symbolism, leaving only nature, industry, and reason. It started on the Autumn equinox. It was divided into 12 months of equal length, 30 days, and ended with 5 (or 6) monthless days of festivals at the end of summer. The months had no weeks, but had three décades instead: periods of 10 days, named after numbers. Primidi, duodi, tridi, quartidi, all the way to décadi. Instead of Roman gods or Christian observances, the months and days would be associated with symbols from nature and farming. The names of the months in particular were incredibly poetic: Vendémiaire, Brumaire, Frimaire in Autumn; Nivôse, Pluviôse, Ventôse in the Winter; Germinal, Floréal, Prairial in the Spring; and Messidor, Thermidor, and Fructidor for Summer.

The French Republican calendar was officially used in France throughout the revolutionary period, for about 12 years, from 1793 to 1805 when Napoleon abolished it. It was rather unpopular. The décades, especially, didn’t sit well with most people, including those who defiantly remained religious. The calendar’s method of calculating leap years was contradictory and didn’t work well. (Pope Gregory XIII, in heaven, is laughing derisively.) And of course, no other country ever adopted it.

Not to mention that its ideal of nature as a universalizing feature was quite the failure. Ventôse, corresponding to February-March, may be the month of wind in Metropolitan France, but it isn’t that everywhere in the world, and not even everywhere in what was then the French colonial empire.

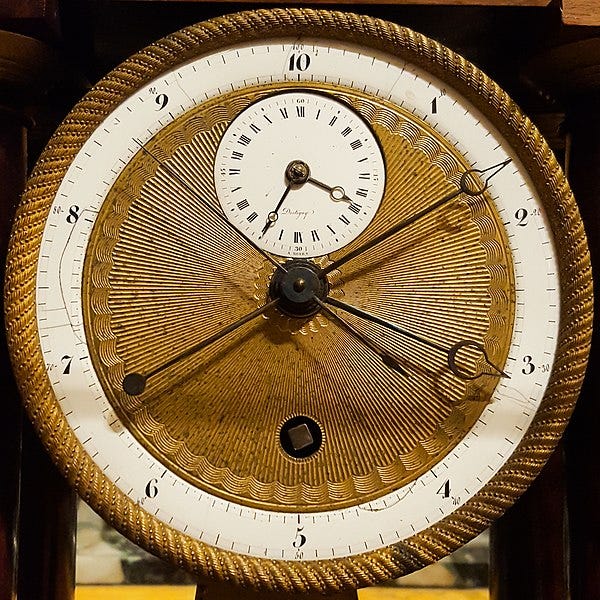

The calendar was but one piece of a much wider goal by the French revolutionaries of decimalizing all systems of measurement. (Science! Reason!) To its credit, it did last longer than the related effort to convert days from 24 hours of 60 minutes to 10 hours of 100 minutes. The French people really hated that.

More successful was the decimal reform of the non-time measurements, like length and mass and temperature, providing the basis for the international system that is now used by all countries except a handful of strange, rebel ones.

In the year 2024 of the Gregorian calendar it seems like a safe prediction that we will never reform it. We’ve tried; we’ve failed. Timekeeping standards are the stickiest piece of technology. Even more impossible to change than keyboard layouts.

In a thousand years we’ll be colonizing the distant stars and still add a 29th day to the month of the purification ritual Februa once every 4 Earth years except once every 100 Earth years except once every 400 Earth years.2

Overall I think that’s good.

I understand the desire to rationalize systems and smooth out the imperfections. But the imperfections are fine. Useful, sometimes, even.

It’s good that my and your birthday falls on a different day of the week every year. Imagine if it had to always be a Monday! It’s good that the month names are kind of meaningless references to ancient Rome — since they’re equally meaningless for everyone. It’s good that you always have to be on your toes for a rogue leap day that comes in and messes up your carefully elaborated yearly schedule.

It’d be fine to have different quirks, or remove some of the dumb self-imposed quirks we’ve created (I am thinking of daylight savings!). But the truth of the matter is that the Earth’s orbit around the Sun is slightly weird, unaligned with the Earth’s rotation. So there will always be some quirks. Why not celebrate them?3

So: Happy 29th of February, everyone! Spend the day well; do something memorable. It’s not often that we can enjoy being outside the calendar, even just as a manner of speaking.

Four countries have not adopted the Gregorian calendar as their civil calendar (i.e. for administrative purposes): Iran, Afghanistan, Nepal, and Ethiopia. Some others use a slightly different version of the calendar (e.g. differing on how they count the years, as in Japan) or use a traditional calendar alongside the Gregorian one for civil purposes.

It seems a reasonable guess that to we will change the main human calendar only if Earth ceases to have a dominant role in human affairs, so that its orbit really doesn’t matter anymore. But of course far-future predictions are extremely uncertain.

Oh god if I’m not careful I’ll end up defending the stupid Fahrenheit temperature scale. Let it be known for the record that I am fully against it and I consider those arguments Americans like to bring up like “Celsius is good for water, Fahrenheit is good for humans” or “Fahrenheit is nice because it intuitively goes from 0% hot (0°F) to 100% hot (100°F)” to make absolutely zero sense.

you might be intrigued by 'the dean second': https://open.substack.com/pub/michaeldean9/p/abolish-leap-year-by-2035?r=2cys&utm_medium=ios

I’m not sure how far our idiosyncratic month names traveled outside European cultures. For example, in Chinese and Korean, the months are simply called “month 1”, “month 2.” And so on.

Chinese even labels the days of the week as “day 1”, “day 2”, etc., except Sunday, which is “sky day.”