The Case Against Choose-Your-Own-Adventure Education

AWM #83: Freedom versus structure in universities (and also in stories and games) 🎓

Once upon a time, I was an undergraduate student in biology, and I had to take a course called “BIOL 301: Cell and Molecular Laboratory.”

This practical course mainly consisted of a (loooong) 6-hour laboratory period every week. It taught the basic “wet lab” techniques used in the part of biology that studies the small stuff: cells, proteins, genes, etc. Because this small stuff is fundamental to the life sciences, BIOL 301 was a required course for everybody in the biology program, which was hundreds of people. But it was a lab course, which means that the university couldn’t just fill up an amphitheater with a giant audience of biology majors and pre-med students: it had to hire teaching assistants and provide lab equipment. Only be a few dozen people could take it at once. As a result, the course filled up fast every semester.

Being not incredibly interested in cell and molecular biology, I didn’t make it a priority to get into BIOL 301. I ended up taking it in my final semester, when an administrator overrode the course capacity limit to let me in. And so I learned about all those basic techniques right when I was about to finish my degree.

It wasn’t optimal.

By that time, I had taken several theoretical courses in cell and molecular biology. All that theory, of course, derived from the techniques that I hadn’t learned yet. To me they were abstract, and that made it difficult to fully grasp the contents of the course. I did well enough on the exams, but I didn’t learn much.

With hindsight, it’s possible that my lack of interest in cell and molecular biology stems precisely from that abstractness. If I had taken that lab course early, before I learned about the theory, maybe I would have enjoyed small-scale biology better? Maybe I would not have eventually picked evolutionary biology as my specialty; maybe I would not have dropped out of biology altogether. Who knows?

Primary and secondary education is typically quite structured. University-level education, by contrast, tends to have free form.1 You are an adult, and so it is expected that you know what to study. Sure, there’ll be a few hard requirements (such as BIOL 301), and some courses will have prerequisites so that instructors can assume some background knowledge, but otherwise you can do whatever you want.

As my friend Daniel Golliher writes (about political science degrees, but it applies to biology too), it is “an a la carte menu masquerading as an education.” Daniel further asserts that this makes political science graduates very ineffective at actually understanding politics and getting involved in the public sphere. As he puts it:

This lack of structure and ordered progression of knowledge has stalled generations of minds. Students who learn well do so in spite of the system, and only because of extra initiative on their own part.

Certainly, extra initiative can help. Had I been better at structuring a biology education, I could have identified that BIOL 301 was crucial to understand the rest, and asked an administrator to get into it early. But then again, if I had been better at identifying what matters in my education, I would probably not have studied biology at all and went straight to computer science, as I did a few years later.

Indeed, why would a 19-year-old be expected to be any good at structuring an advanced education? That seems very much to be the job of professors, teachers, and university administrators.

Of course, allowing some degree of freedom in education can be beneficial. Indeed, the lack of freedom in primary and secondary school can be disastrously stifling for creativity — hence the common comparison of school with prison, which is perhaps hyperbolic but often rings dishearteningly true. So a good university program should allow freedom for those who truly want and need it; but for others, it should provide much more structure than it currently does.

Let’s discuss the tension between freedom and structure. We’ll use books as a metaphor, because what are books for if not providing good metaphor material.

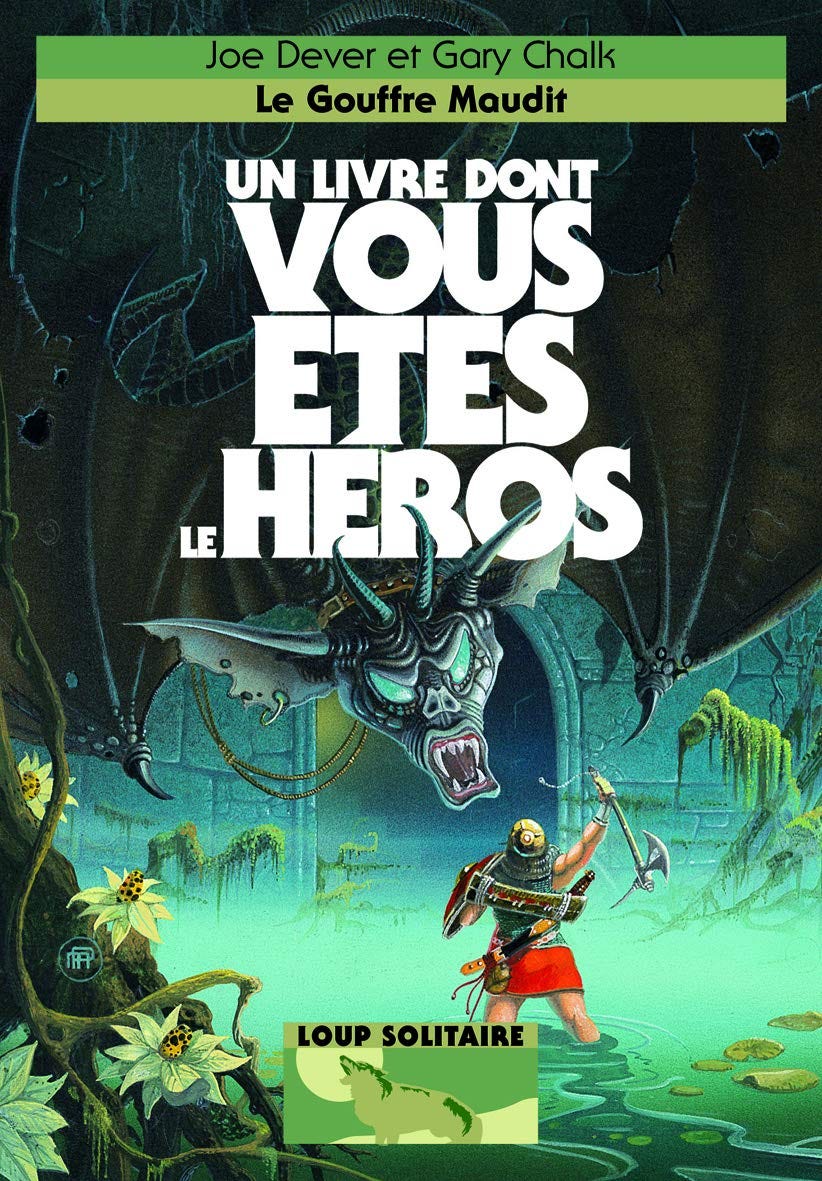

There was a period in my life, at the age of 11 or 12, when I mostly read choose-your-own-adventure books. I should say gamebooks, because “choose-your-own-adventure” is a trademark, but whatever. You know what I’m talking about, of course: they’re books in which the first paragraph tells you you’re entering a dark castle, and then asks you to choose between exploring the great hall (go to page 54), the tower (go to page 19), or the dungeons (go to page 102). Then you make more choices, flip a lot more pages, and eventually either complete the story or die (at which point you’ll probably want to back up to explore another forking path).

My understanding is that by the early 2000s, when I was reading them, gamebooks weren’t particularly fashionable anymore. They had been more culturally relevant in the 1970s and 1980s.2 In the early 21st century, if interactive fiction was your thing, there were plenty of video games to play instead. But I was a kid, and kids tend to be encouraged to read books instead of playing video games. Gamebooks were a loophole: I was reading words printed on paper, but also playing a game! So that’s what pre-teen Étienne read the most.

But maybe pre-teen Étienne would have been better served from reading regular fiction. (And he would do that soon enough; I believe I read The Count of Monte Cristo soon after that period.) I have nothing against choose-your-adventure books, but we can probably all agree that none of them are masterpieces of literature. They’re just fun and cheap entertainment.

Meanwhile, the actual masterpieces of literature aren’t interactive. They’re linear. They are the work of a genius author who aligned words in such a way that it elicits emotion, thrill, and growth in the reader. You don’t need interactivity for any of that.

When you read (or watch, or listen to) a book, essay, article, movie, theater play, video, podcast, or any other non-interactive media, you implicitly rely on the author’s choice of structure. You don’t have to come up with your own. This is usually the wiser choice. Why should the reader (or viewer, or listener) be expected to do the hard work of structuring the media they consume?

Games, whether in print or in code, provide an answer: interactivity gives you a totally different kind of experience. Games are often more immersive. They’re less passive. They simulate real life better, too, since in real life you have to make decisions all the time. And all of this is right! But it does come at a cost. Interactivity — especially the kind that allows the most freedom, such as open-world video games — poses many constraints that get in the way of telling stories or teaching ideas. Figuring out the structure of the open universe of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, for example, can be a lot of fun, but it also requires cognitive effort that may detract from, for instance, understanding a narrative. A story set in an interactive open world is also much more challenging to write.3

In practice, the best story-based games are probably those that rely on a well-structured narrative, but still provide freedom to the players who want it. You should be allowed to either follow a beautifully laid out path without thinking too much or explore an open world in an unstructured way to find fun secrets.

And if you’re an experienced fiction reader, you may recognize that all books allow this by default. Books are linear, but that doesn’t prevent you from jumping ahead, to read chapters in any order, or even to imagine the bits of the story that aren’t written down. Books are structured, because having a read a bunch of randomly ordered pages would be no fun. But to the most daring books whisper, “You can do whatever you want with me. You don’t have to follow the rules.”

Back to education. How much sense does the analogy with books and games make? Should education really be made more linear, with the option of freedom to the students who seek it?

I’m probably not the best person to answer this question. I am no education specialist. I don’t have much practical experience of teaching a course or organizing a study program. And I’m sure that these things are full of nontrivial challenges.

But what I do know is that education, especially university-level education, is warped by a bunch of perverse incentives. Students, nowadays, frequent universities primarily for the credentials, the prestige, the signals that it sends to employers; and not so much for the learning. Meanwhile, universities are motivated to accept students because of the funding they get, rather than by a sacred mission to elevate their minds. I’m deliberately painting a damning and exaggerating picture, of course, but you get the idea.

It seems likely that the choose-your-own-adventure model of education evolved due to those incentives. Students care about the degree, not the contents of the courses — so they might as well pick and choose from an a la carte menu. Universities care about satisfying student preferences (to attract and retain them, much like a company must woo customers), so with time they implemented menu options.

And then eventually we got where we are, in a world of isolated courses, taught by overworked researchers who don’t know and don’t care what the other courses teach. Of student advisors who play an optimization game to make sure their students have obtained sufficient course credits and all their prereqs. Of students who are left alone to figure out why exactly they are pursuing a major in biology or whatever, and who end up working towards the only legible goal that is given to them: passing all their courses and getting good grades.

Students are thrown in an open world game, and are supposed to somehow follow a story that barely anyone tells them about, while they can easily rake up arbitrary points by completing random disconnected subquests. No wonder that they later barely remember any of the main plot.

It feels a bit strange to argue against freedom. I know very well that freedom is the key ingredient of many nice things, from good art to good scientific research. So let’s make one thing clear: choose-your-own-adventure education should not completely disappear.

What should happen is that choose-your-adventure education would be picked by a minority of students. They would be the extremely curious and motivated. Those who are clear on what their goals are and who realize that these goals can’t be fulfilled with any of the many regular paths.4 It would be the “hard mode” of the game, at least from the point of view of structure.

For the others, there should be a beautifully laid out path that helps them learn and achieve a goal, depending on the program they chose. That path wouldn’t be the “hard mode” at the level of figuring out a path, but that doesn’t mean it would be easy to complete. In fact it would probably be harder than the current model, because there would be more prerequisites and less possibility to replace a hard course with an easy one. And note that the goals would still be very open-ended: being effective at politics (if you study political science), understanding the fundamentals of life to eventually push the boundaries of knowledge (if you study biology), etc.

For this to work, the structure would have to be really well thought out. Universities would have to take the task of designing programs much more seriously. And they should offer much more guidance to the students, both when choosing a goal and when picking a forking path. And for the few who, despite the warning, decide to go the choose-your-own-adventure route, it should offer support, flexibility, and ways to go back on the regular path if full freedom doesn’t work out.

Would universities be willing to implement this ideal? Probably not, because of all the current incentives. But there might be a good reason for them to do it anyway.

It is becoming increasingly trivial to learn anything from the internet, if you’re sufficiently motivated. However, there is so much information that it’s easy to get lost. On the web, the challenge is not in finding stuff to learn, but in deciding what to learn. It is a vaster choose-your-own-adventure game than universities could ever hope to be.

So perhaps universities could (re)specialize in providing the structure that the internet doesn’t. It would be a way for them to remain relevant thanks to the education they give rather than by relying on prestigious credentials. And if that has the side effect of making them uphold the sacred mission of elevating their students’ minds — well, I wouldn’t complain.

At least, university-level education has free form in the fields that aren’t meant to attain specific professions. It seems likely that degrees in medicine, law, or engineering are more structured than biology, political science, literature, or computer science. But I haven’t studied any of the former.

Bandersnatch, the Netflix Black Mirror interactive movie that is a tribute to gamebooks, is set in 1984.

The difficulty of adding interactive elements to media is probably why it’s rare in educational materials. Here I mean interactivity in a “narrower” sense: things like adding a little physical simulation widgets to a web article, which help readers grasp concepts faster without requiring them to figure out the whole structure of a text. For instance, this paper. Such things can be really neat, but they add a big layer of complexity for authors.

My university offered the possibility to do a dual B.Sc. and B.A. instead of simply picking a major from either the Faculty of Science or the Faculty of Arts. But they made it clear that this was for students who knew what they wanted. It was absolutely not for those who didn’t know what major to pick. That’s a good example of giving freedom only for those who truly want and need it.

Your description of the perverse incentives in course selection matches my experience perfectly. The current system seems to have arisen from the conflicting aims of providing students with a broad liberal arts background and preparing them to join the workforce (or for further, more serious study).

Challenging that does feel a bit pointless though if students don't go to school to learn, and schools don't accept students to teach them, and employers don't care about any of that.

The British system seems like a good alternative, where both core and elective learning are condensed into earlier years, and students then commit to much narrower scopes of study (A levels) before progressing to university. So the bridging between aims and expectations happens well before higher education.

I enjoyed this!

I went to a university significantly more rigid than your experience, and we chafed at it, so I want to defend freedom.

To be somewhat contrarian, your example seems to be like the system working as intended. The lab course is quite costly to the university per student and it's better if only those really interested in molecular biology take it. You mention starting out not interested in mol bio... and ending up not interested in mol bio. This seems fine. Did the evo bio courses go well?

More generally, it's true that 19-year-olds might not know how to design their own education, but there's a much better solution than forcing everyone to take the same courses in the same order - asking people, especially older students in the same major and people who just graduated (apart from college advisors whose job it is to help you with this). In college I chose to take courses based on gossip from seniors about which profs taught well, which courses were pre-reqs for others - which worked out quite nicely.

A nice system some universities have is fairly structured majors, plus the option of designing your own major for students who know what they want to do doesn't fit into a pre-defined major. This seems like the best of both worlds.