The Difference Between Science and the Humanities Is Reading the Classics

AWM #75: On what distinguishes the two main branches of knowledge 📜

For centuries a great has been waged across the universities and places of learning of the world. On one side of the battlefield: science, with its legions of biology, physics, chemistry, mathematics, and countless battalions and divisions within them. On the other side: the humanities, organized into the armies of philosophy, literature, history, the arts, and theology. (And in between, changing camps as they see fit, the “social sciences” of sociology, economics, political science, psychology, linguistics, etc.)

Why do we divide the academic disciplines thus?

It wasn’t always like this. In our early history, all the branches of knowledge were enmeshed together — myth and religion were indistinguishable from explanations of the natural world or from moral justifications of government systems. Later, when the pursuit of knowledge became independent from mythology, it was all considered to be under the umbrella of “philosophy.” Thus the first speculation on atoms or on the nature of the universe was done by ancient “natural philosophers” who could hardly be described as scientists in the modern sense, and whose expertise often included fields that are decidedly outside modern science.1 Aristotle, for example, is considered the father of both biology and political science. And that’s leaving aside the enormous breadth of his work, from poetry to physics to ethics and many other topics.

Yet today students have to decide whether they’ll study “science” or “the humanities.”2 Universities place them in completely different faculties. The norms of what constitutes good intellectual work differ between them. Academics identify to either one and may even scorn the other side. There are blogs dedicated to bridging the two cultures of the sciences and humanities, which implies that there exists a chasm.

It’s clear that these two cultures exist. I’m not claiming that the distinction is fake. But what actually is the difference? Here are five possible answers.

1. Experimentation

Modern science was born in Europe starting in the 15th century. Its hallmark is the scientific method (a… rather circular name), with a focus on experimentation. This provides our first common distinction between the branches of knowledge: Science is whatever can be studied by experimentation. Whatever cannot be is something else, like pseudoscience (invalid studies that try to pass as science) or the humanities.

This distinction doesn’t really work.

For one thing, there’s plenty of stuff we consider scientific but that we can’t experiment on. For example, much of astronomical research relies on observation rather than experimentation. You can’t recreate a mini-Big Bang in a lab to validate your model of the early universe — and yet cosmology is neither a pseudoscience nor one of the humanities. In other cases, experimentation is theoretically possible but is unfeasible for practical or ethical reasons. Introducing a new rodent to an island would be a valid method to study the ecology of invasive species; but it would disrupt the island’s environment and cause a bunch of problems, so it’s not an acceptable experiment. That doesn’t mean that the ecology of invasive species isn’t a proper science.

For another thing, you can totally experiment with the humanities. You could A/B-test Shakespeare, if you wanted. Divide a group of people in two, make one half read Julius Caesar, another Romeo and Juliet, and then run a survey on their impressions. You’ll gain knowledge from experimentation, even if the knowledge of which Shakespeare play this particular group prefers is not necessarily super useful.

Also: there is some debate over whether mathematics is an actual science, but it’s usually lumped together with the rest of STEM. It’s certainly never described as one of the humanities. Math involves little to no experimentation, but it seems scientific anyway.

Experimentation is great, and its standardization as a way of gaining knowledge during the Scientific Revolution was a great advance. But it’s neither necessary nor sufficient to obtain valuable new knowledge, scientific or not. It doesn’t, on its own, provide a good distinction between science and the humanities. (And the social sciences blur the line even further. You can run a microeconomics experiment, maybe, but not a macroeconomics one. Is economics an experimental science or not?)

2. Nature vs. Humans

Perhaps the answer is instead in the name humanities? Science focuses on the natural world; the humanities (and the social sciences) focus on the affairs of humans. The distinction therefore follows the same line as the common opposition between nature and humans.

One facile response to this is that humans are part of nature, so the distinction is meaningless. While this is technically true, it’s not a very useful way to think about the world. Humans are special — we make things, such as cities, art, concrete, computers, and science itself — that are unlike anything made by other animals, life forms, of physical processes. As the physicist David Deutsch puts it, humans are entities that can create explanatory knowledge, and nothing else can (that we know of).3 So it does make sense to distinguish the natural and the artificial. Having this latter word gives us an extra tool to understand reality.

And yet that doesn’t really help us understand the science-humanities distinction. A lot of “science” studies humans, the most obvious example being medicine. You could say that medicine is concerned with studying the parts of humans as biological objects that aren’t closely related to human culture, but many branches of medicine have a clear “humanities” vibe, including epidemiology, public health, and family medicine. Engineering, which is an applied science like medicine, is also very much concerned with the needs of humans despite being about as far from the humanities as it gets.

Conversely, a lot of the humanities are concerned with nature. Anthropology — the quintessential field of human affairs — doesn’t make sense if you don’t study the human being as an animal in its environment. Linguistics studies natural languages that have arisen without conscious engineering, unlike constructed language such as esperanto. Philosophy happily delves into deep questions on the nature of the universe or abstract entities that have nothing to do directly with humans.

(Once again here is a parenthetical statement to mention the social sciences, which in this frame seem to be clearly closer to the humanities than to science. Indeed, some of my examples in the last paragraph might be closer to the social sciences than the humanities.)

There clearly is a distinction to be made between knowledge about humans and their civilization on one side, and knowledge about nature on the other. But that’s not really what science vs. humanities is about. You can study human things scientifically, and you can study natural things through art, literature, and philosophy. This isn’t quite the answer we’re looking for.

3. Objectivity

Some may say that science is more objective — more factual — than the humanities, which allow a measure of subjective judgment. I don’t think that’s usually true. Both are concerned with finding true knowledge; both can make mistakes; both depend on subjective human interpretations.

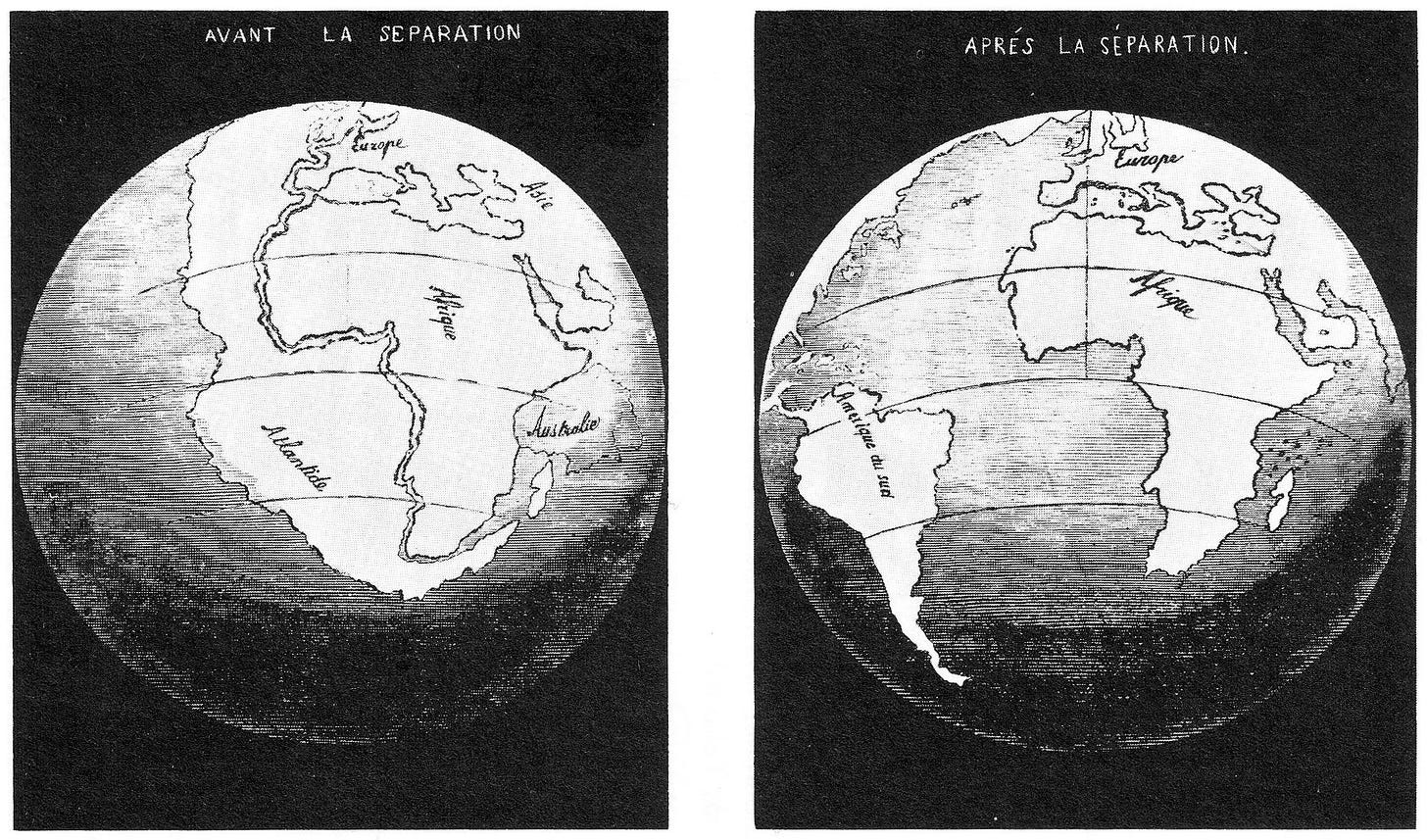

Some philosophical questions, for instance around morality, are extremely difficult to answer. But there should always exist some true answer if you define the question precisely enough. Similarly, some history questions are most likely unanswerable since there is no historical record that could answer them. But that doesn’t mean that history is subjective, or at least not more than a scientific pursuit like reconstructing the history of plate tectonics.

I’m including this section because I have a feeling it will be mentioned if I don’t, but frankly I don’t find the objectivity-subjectivity debate that interesting. Every piece of knowledge is mediated by human consciousness and is therefore subjective to a degree; every piece of knowledge is also factually true or false in reality and therefore objective. Maybe it’s true that science ends up studying those for which the objectivity is more evident, while the humanities are interested in things like art that allow for a subjective appreciation. (And the social sciences try to be objective like the hard sciences, only to fail because they deal with messy human affairs that rely on A LOT of interpretation.) But even so, that doesn’t seem like the main distinction.

4. Complicatedness

Science is complicated. In school, it is meant for the brightest students. It leads to higher salaries because fewer people can do it. It relies on unintuitive tools, like advanced math, that only smart people can comprehend. At the extreme, some sciences — such as quantum physics — are so complex that even the majority of science-educated people can’t even hope to understand them. We call this part of knowledge the “hard sciences,” because science is HARD.

The humanities, by contrast, are simpler. What they study is centered on humans, so their theories are always easier to understand. Art and literature wouldn’t be interesting if they were too complex and abstract. While science requires people to know how to read, write, reason, and use math and programming, the humanities just rely on the first three. So they are much more accessible — and much easier to get an A for in a college course.

(Here the social sciences are a mixed bag: they’re sometimes described as the soft sciences, but at the same time, nobody truly understands macroeconomics.)

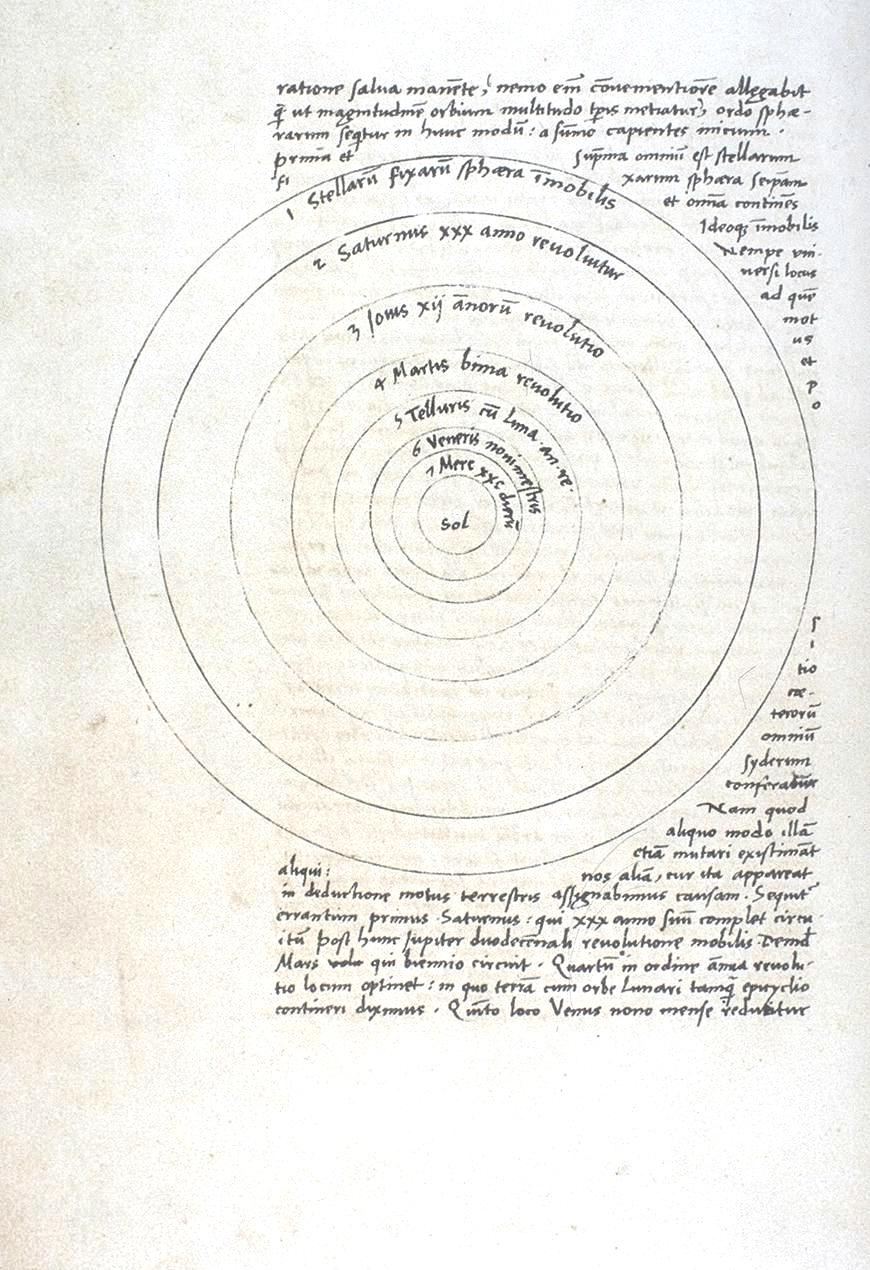

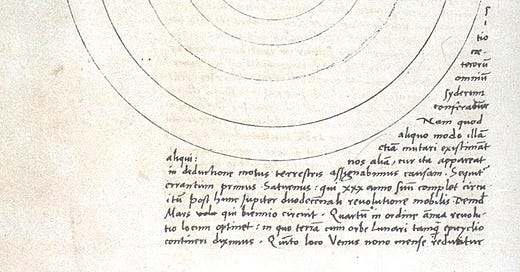

My instinct is to say that this is a dumb argument. The humanities can be extremely complex — just think of elaborate philosophical arguments, such as Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason — while there’s plenty of science that is simple to understand. Natural selection, for example, is at its core a straightforward argument. So is heliocentrism. When you think about “science,” you may naturally tend to think about complex current questions (like the multiverse interpretation of quantum physics), but a lot of our understanding of the natural world is simple enough that it was settled a long time ago. That doesn’t make it unscientific.

Yet is there a grain of truth here? Science does use math much more than the humanities do, and math really is counterintuitive to our minds. The separation of STEM and non-STEM students, whether desirable or not, is real. My own experience growing up proves that smart students are very commonly pushed to the scientific fields even if they are not that interested in them.

Complicatedness is not a good way in theory to distinguish science and the humanities. But in practice, it may well be the cause of the split into two rival cultures. The ones who can do math, and the ones who can’t.4

5. Reading the Classics

But while the STEM students do more math, there’s one thing that the humanities students spend far more time on than the science types: they read old texts.

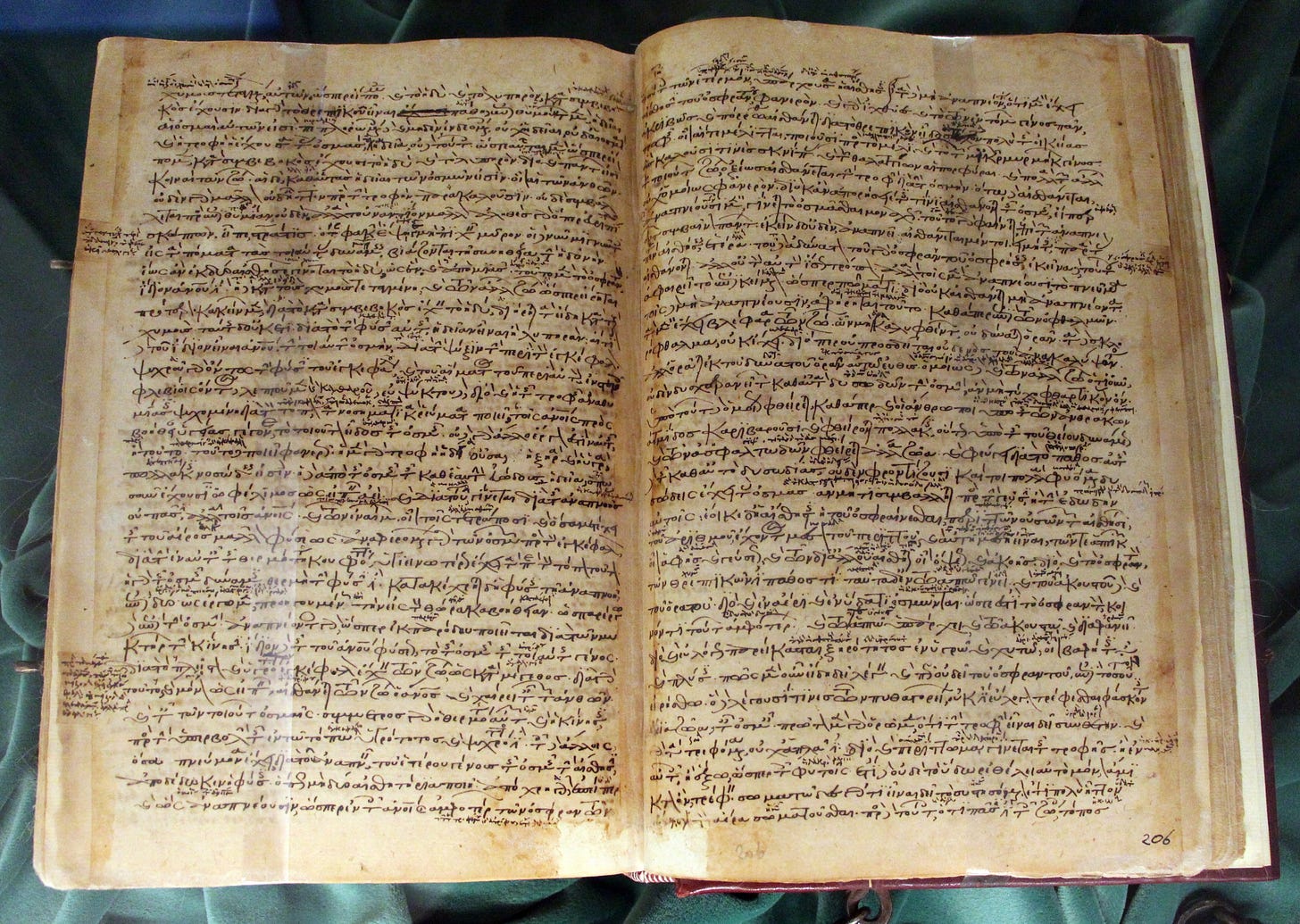

If you’re interested in philosophy, you have to read Plato and Aristotle — and Kant, and Nietzsche, and Sartre, and so on and so forth. If you’re interested in English literature, you have to read Shakespeare and many others.5 If you’re interested in religion, you have to read the old sacred texts as well as theologians from centuries ago. It’s fine to read about all these famous philosophers and poets and thinkers, but it’s no substitute for the real thing.

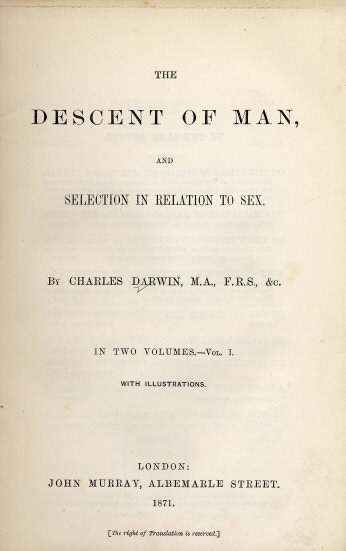

In science, this doesn’t apply. A physicist needs to know about Newton and Einstein’s ideas, but doesn’t need to read the Principia Mathematica or “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies” in the original German. A biologist must have a solid grasp of Darwinian evolution, but reading On the Origins of Species is interesting for its historical value only. If you just want the science, you might as well read a recent textbook or paper.

Why is that? The first answer is that science doesn’t really care about who came up with good theories. Scientists care a little bit, because they’re human and humans like to hear about the achievements of other humans. That’s why you know Einstein and Darwin’s names. But it doesn’t really matter how they presented their findings, what style they wrote into, or what they actually believed.

The second answer is that Einstein and Darwin’s findings have been improved upon many times since they were first published. Scientists care about the world as it is; since Einstein and Darwin, being further away in time, got many small details wrong, then their work isn’t so useful anymore. It’s better to read a synthesis by whoever came up with a theory that fixes the initial flaws, allowing our knowledge to inch closer to reality.6

As a result, Einstein and Darwin and the others (like Copernicus or Aristotle as a biologist) end up being read only by a specific kind of people: historians and philosophers of science. Their field is squarely a part of the humanities, despite studying the other side of the great chasm of knowledge. This peculiar situation makes them uniquely unlucky among humanities people in that they have a fairly poor reputation among the people that they study (and purport to help): scientists themselves. For example, the physicist Richard Feynman famously said:

Philosophy of science is as useful to scientists as ornithology is to birds.

I don’t know whether Feynman was right on whether the philosophy and history of science are useless to scientists, but he certainly was right that scientists don’t read them. And so here we have an interesting distinction between the humanities and science: one reads its classics; the other acknowledges them but leaves them aside.

This can lead to several interpretations of how science and the humanities work. One is that science has a clearer idea of progress towards truth, and as a result it obsoletes itself faster. When you cite, today, a paper from the 19th century, it’s usually because no one improved upon the particular point you’re making in more than a hundred years; if someone had done so, you’d cite them instead. So we can say that little progress has been made on this question.

Such a view can be interpreted as damning for philosophy and the other humanities. If we read Plato today, is it because nobody in 2,500 years has improved upon Plato? Surely in all that time someone would have fixed some of the flaws in Plato and come up with a better philosophy? If yes, why is that person not more famous than Plato? If not, does that mean that philosophical progress is not possible?

But the next interpretation salvages the humanities’ view somewhat. Reading the classics isn’t meant to attain truth as fast as possible. It’s meant to give an understanding of how to attain truth. You read Plato not because Plato was more right than anyone who came after, but because it’s useful to know where our ideas come from, what the context that allowed them to appear was, and crucially, what the flaws of Plato were and why he had them. The errors are an important part of the story too.

To make a bit of commentary on the current state of affairs, I think that most modern scientists (and this includes social scientists) often lack hindsight. They don’t actually understand how science was done in the past and what led us to our extant scientific knowledge. When you only read textbooks and papers from the last 5 years, your views will necessarily lack a lot of depth. This is the pitfall that students of the humanities are trained to avoid.

One illustrative consequence of this, in my opinion, is poor writing style. Scientists have no idea how science papers were written a hundred or two hundred years ago. So they replicate the style of the very recent papers they read without even being aware that there is a better way. (This is, of course, what I study at my other blog.)

Any exercise in defining a concept tends to end up with an unsatisfying answer like “well, there’s no absolute answer, it’s complicated, it’s a mix of things.” In biology, there is no single criterion to distinguish species. In linguistics, there is no single definition of what a word is. In epistemology, there is no clear-cut boundary between science and the humanities (and the social sciences).

All my answers above have some truth to them. Science is usually experimental, objective, complicated and full of math, and concerned with nature. But take out one of these criteria, and it’s still science. Take all or most of them out, and then we get the humanities: a field of knowledge that usually is less experimental, is simpler to understand, leaves the door open to subjective judgment, involves no math, and studies humans.

Yet my last answer — reading the classics — rings surprisingly true. Scientists really don’t read their classics much, while humanities people are obsessed with theirs. So if you really must select one criterion to distinguish them, that might be it.

(It gives a pleasantly nuanced answer for the social sciences, too: a social science that still reads old thinkers is probably closer to the humanities, while another that is more concerned with the latest papers is closer to the sciences.)

I do wonder if perhaps it might be a good idea to reduce the width of the chasm a bit; to propose a ceasefire between the two warring camps; to unify the branches of knowledge into a single trunk once more. Maybe philosophers, historians and theologians should focus a bit more on making their field progress towards truth rather than write an ever-increasing amount of commentary on the old thinkers. And maybe physicists and biologists should actually go and read Einstein and Darwin’s original texts. They might learn a thing or two.

In the ancient sense, “science,” from Latin scientia, just means knowledge.

Or other things, but science and the humanities are the main branches of abstract, academic knowledge. The more practical fields — specific arts like painting or music, or applied sciences like engineering and medicine, and yet other topics like law or business — are distinct, though often closely related to one or the other.

The only known non-human process that can create knowledge is evolution through natural selection.

I resisted a “the ones who Kant” pun here.

I’m not quite sure which are the most important authors since I’m not that interested in English literature. The classics of French literature are clearer to me: Rabelais, Molière, Racine, Voltaire, Balzac, Hugo, Baudelaire, Verlaine, Dumas, Zola, Gide, Camus…

These two reasons paraphrase David Deutsch’s observations in the chapter “A Dream of Socrates” of the book The Beginning of Infinity.

This was such a fascinating piece to read; I learnt a lot from this! Thank you so much for writing this! Is it true that paradigm shifts are often made by those who are from a completely different background/field of study to the one they make the paradigm shifting discovery in? If true, what could be contributing to this pattern?

Hello,

Bonjour,

What do you think about Karl Popper’s falsification criteria for science ?

For me, it draws a useful restriction of science to what can be « predicted », either logically, differentially or statistically, thus excluding most of humanities, dealing with humans that can actually want to game the predictions.

Moving from science to predict,

to conscience of what you want to predict.