The Four-Way Tradeoff of the Writer

Which one are you willing to sacrifice: clarity, brevity, information richness, or complexity? 📄

I’m currently writing an essay about scientific writing style. As a demonstration of what I think is good style, I rewrote a paragraph from an evolutionary biology paper1 that I consider not very good at communicating its content.

My rewriting made the text much clearer (in my opinion!), but I also more than doubled its length, from about 200 words to 500. It makes sense: I added examples, some explanation, transition words. I think those additions help a lot with understanding the material — but of course that comes with a cost, especially if you have a word limit.

So I wondered: is there a tradeoff between clarity2 and brevity?

There can be, I realized, but clear and brief content can exist (and indeed is an ideal most writers should aspire to). The reason I wasn’t able to maximize both in my rewrite was that I couldn’t alter the amount of given information, since I didn’t want to change what the original authors meant.

And the original authors were expressing a lot of information in that paragraph. Since, presumably, they also needed to be brief (the word limit is a harsh mistress), they had to sacrifice clarity.

This suggests a three-way tradeoff, between clarity, brevity, and a third component that measures the amount of information given.

I called it “quantity” in that tweet, but that was a bit vague. No term seems to capture it well enough — I hesitate between “information density,” “informativeness,” “entropy,” and “richness.” I’ll go with richness.

So the idea is that you have to sacrifice one of the three:

If you want to express a lot of ideas in a short text, you can’t explain and illustrate, thereby sacrificing clarity.

If you want to express a lot of ideas clearly, you have to use a relatively large number of words, thereby sacrificing brevity.

If you want to be both brief and clear, then you can’t express a lot of ideas, thereby sacrificing information richness.

This is elegant and satisfying (thanks, rule of three), but is it true that the combination of all three can’t exist? Can something be brief, clear, and information-rich?

I think so. They key is to make sure every piece of information is simple. Then you’ll be able to have a lot of information in a brief text, without compromising on clarity since you won’t need explanations and examples.

But that means we’re sacrificing a fourth quality: complexity. In other words, how difficult a piece of information is; how much explaining it requires to be made clear.

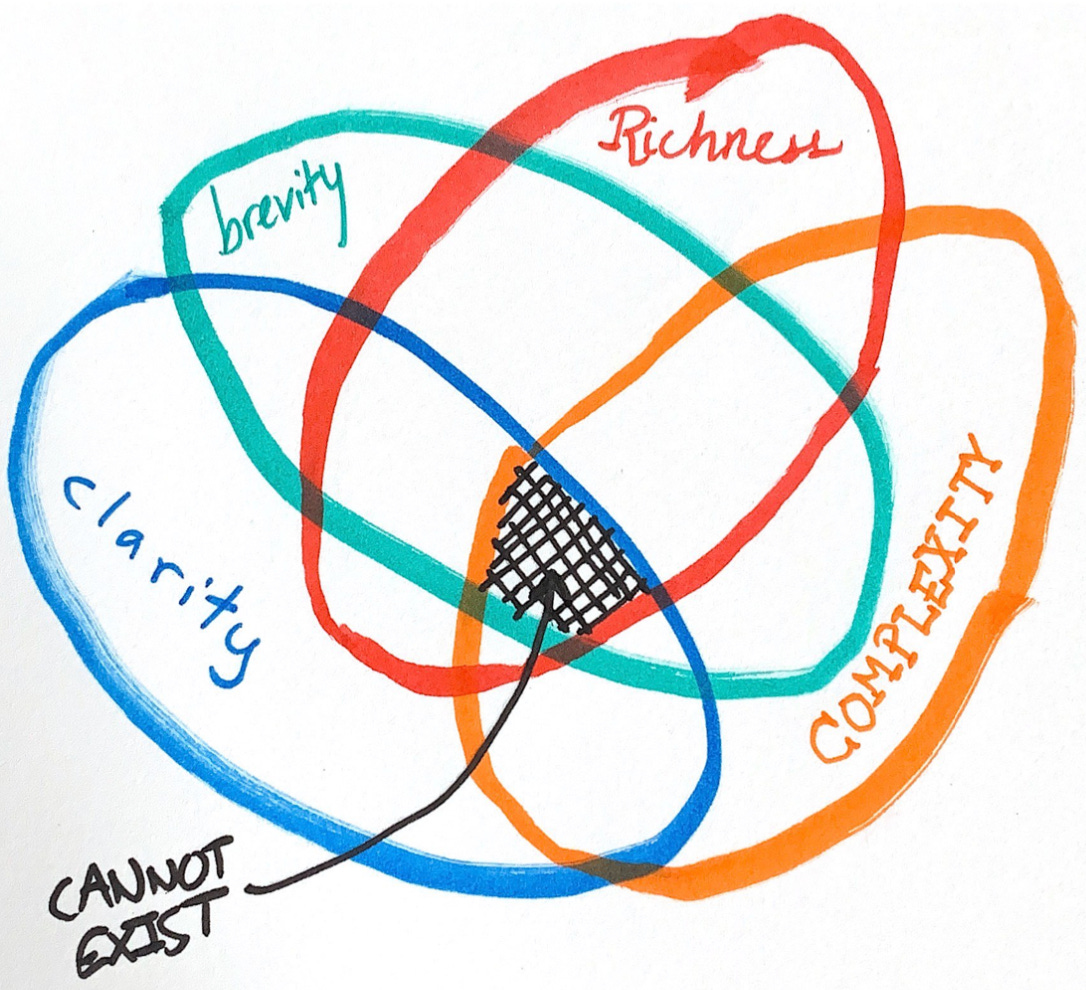

We can summarize the four-way tradeoff thus:

Want to be clear, brief, and info-rich? Sacrifice complexity and stick with simple ideas.

Want to be clear, brief, and complex? Sacrifice richness and stick with a single idea or two.

Want to be clear, info-rich, and complex? Sacrifice brevity and write a long text, perhaps a book, to clearly explain many complex ideas.

Want to be brief, info-rich, and complex? The only way is to sacrifice clarity and write something that’s difficult to understand.

Or, in Venn diagram form:

If you have to sacrifice one of the four qualities, which one should it be?

It’s of course very dependent on context. Often, you’ll want to sacrifice complexity. It’s not even a particularly positive quality — its opposite, simplicity, is usually a good thing to aim for, especially if you write to entertain or to sell. But there’s a lot of complex, difficult stuff that’s worth writing about, in which case we revert to the three-way tradeoff between clarity, brevity and richness.

Richness is another quality that depends on what you’re trying to say. It’s common advice to ensure that your topic is focused, which is another way to say you should sacrifice richness. But sometimes you really need to explore all the angles of a question (perhaps in order to avoid exposing yourself to counterarguments, or because you’re aiming for comprehensiveness), so you don’t always have a choice.

Whether you can sacrifice brevity or not depends on the medium. On Twitter, you have to be extra brief. You also usually need to be relatively brief when writing a newspaper article, an ad, or a science paper. Some genres allow indefinite length, like blog posts and, obviously, books. The longer you write, the more sustained effort you ask from a reader, so be careful when compromising on brevity.

That leaves clarity. Unlike the other three, clarity is rarely subject to strict constraints like word limits or topic choice. So in contexts like scientific papers, it often gets the short end of the stick.

I think this is bad. I think clarity should be the top priority! The reason is simple: without clarity, a piece of writing is far less efficient at its main goal, which is communication. Your important, complicated ideas will never get anywhere if they’re expressed in a way that’s difficult to understand.

Note that you don’t have to maximize exactly three of the four qualities. Indeed, a piece of writing could contain a single simple idea and still be be long and unclear. This, of course, is what we call bad writing.

I suppose it’s also possible to be somewhere in the boring middle, with text that is neither particularly brief or long, clear or difficult, complex or simple, or info-rich or poor. That sounds… middling, at best.

So if you haven’t maxed out three of brevity, clarity, richness and complexity, you should start by improving on one of these dimensions.

In any case, I think the original paragraph I was rewriting was complex, info-rich and brief: it had successfully maxed out three of the four qualities. But in doing so, it sacrificed clarity, which made it difficult to read. This is a common problem is science writing — and one I’m hoping to tackle in my forthcoming essay.

I’ll let you know when I publish it.

Étienne

Link to the paper; the paragraph is titled “Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (Single Stationary Peak) Models of Traits Evolution.” I will make this rewriting work available in a blog post soon.

To be, ahem, clear, clarity here refers to ease of understanding. In most cases, this requires illustrative examples and logical explanations, which can’t be done very briefly.