The Inevitable, Awkward Post About Money

I'm turning paid subscriptions on, hopefully it won't make everything weird! 💰

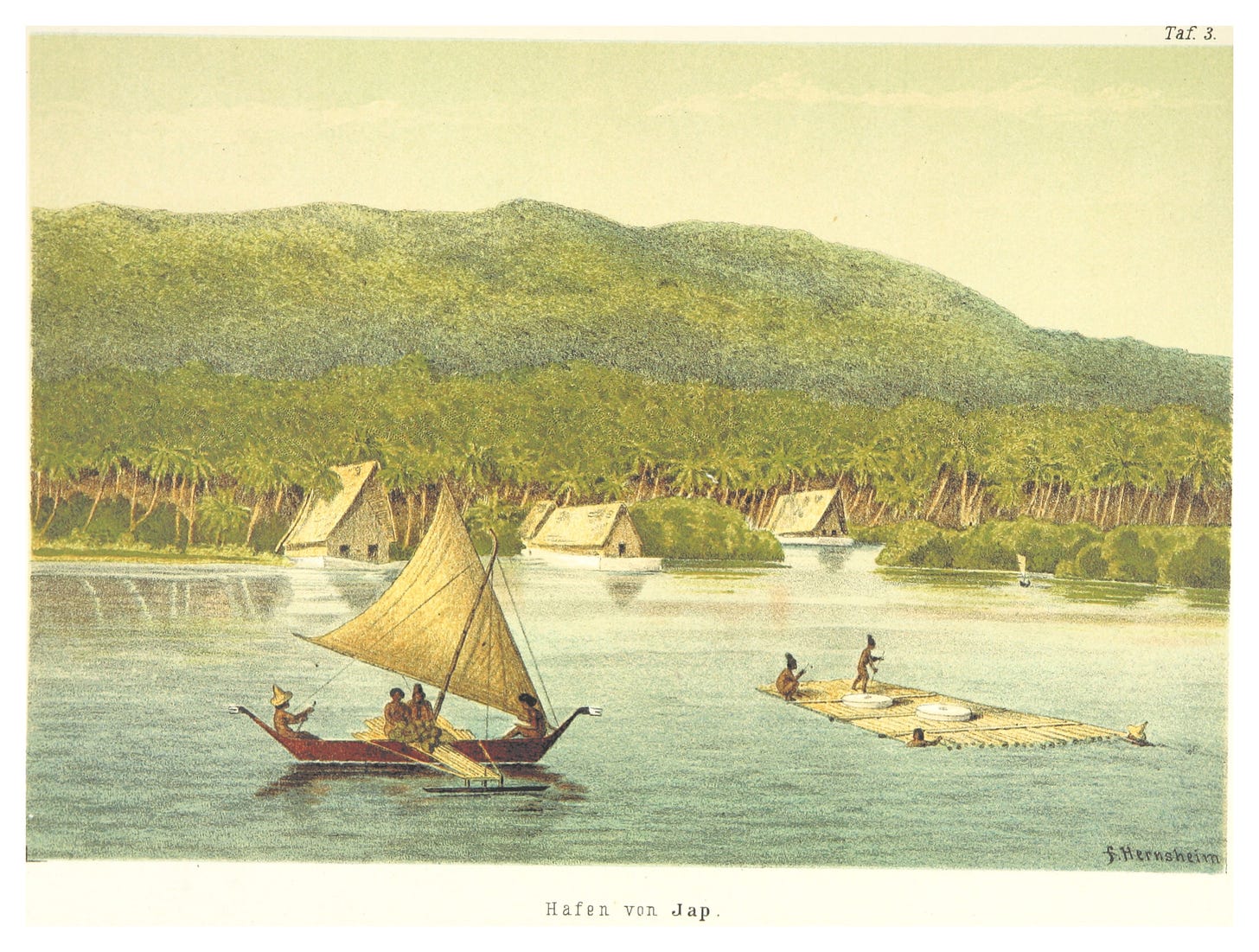

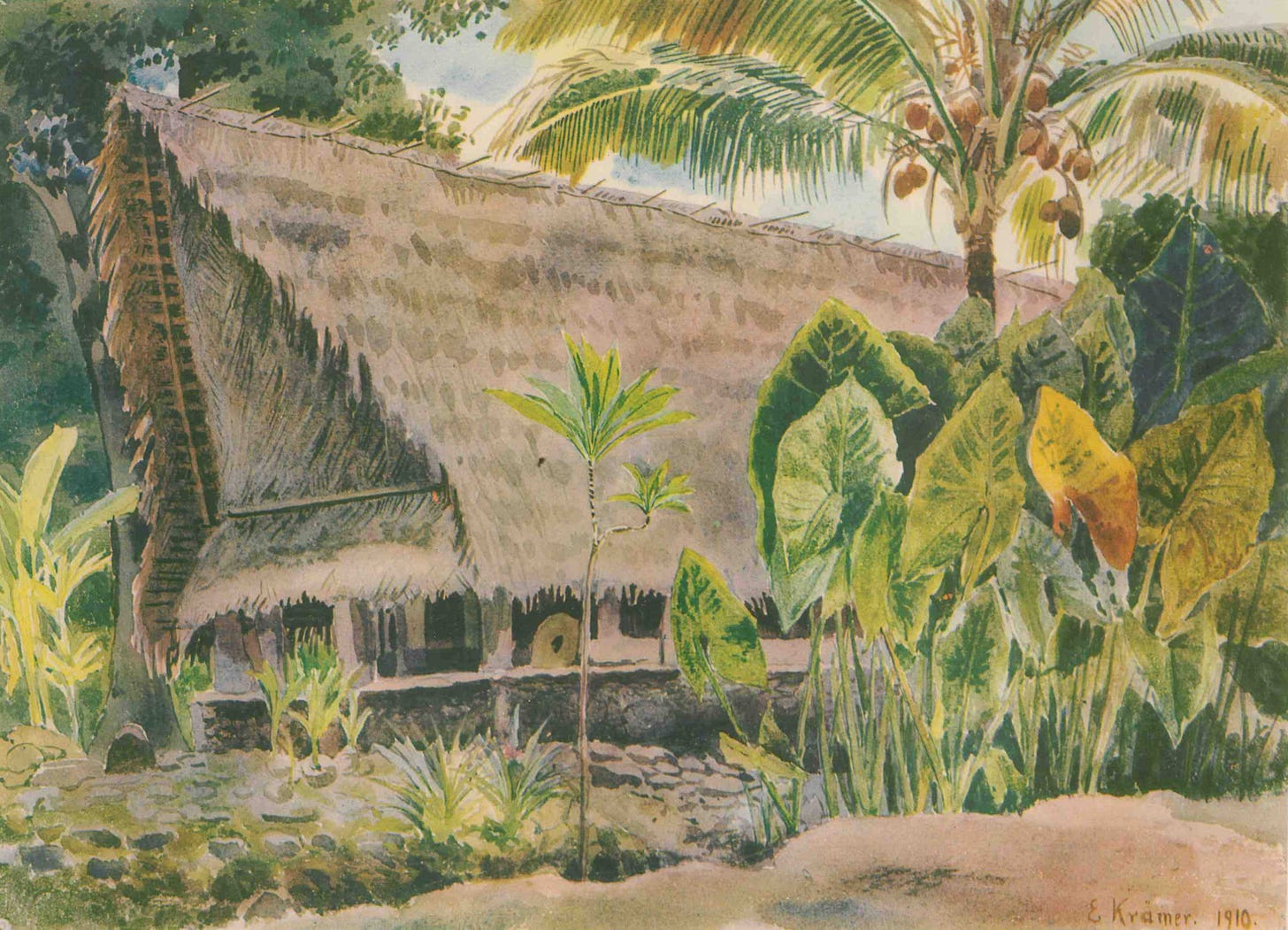

On the remote island of Yap, in Micronesia, it has been the tradition since ancient times to quarry, and then transport from other islands at great effort, giant disks of stone with a hole in them. These “rai stones” were raised at various spots on Yap, and then treasured. Sometimes the Yapese would trade them. They still do, in fact, for important transactions: weddings, inheritances, or political deals. They do not usually bother moving them around — they just know which stone belongs to whom.

Ethnographers and economists have interpreted this system as a very peculiar way to do money. It’s probably a typical case of Western misinterpretation (no, the rai stones don’t follow a prototypical ledger system that foreshadows the rise of bitcoin), but still: if giant disks of stone can be seen as money, what does that say on what money actually is?

It says that money is a really, really weird thing.

Money is weird because it is a proxy for wealth. Wealth is a generic concept, representing whatever people want — houses, cars, luxuries, relationships, health, and so on. Such a generic thing is hard to manage as is, so we use special devices to move it around: metal coins, gold bars, banknotes, cryptographically secure pieces of computer data, or giant stone disks. A secondary use of all of these things is as a unit of measurement. We say that a thing is worth $5, or $5 million, because that allows us to compare with other, widely different instances of wealth.

This dispassionate way of looking at money is fine and all, but in practice most people get hopelessly confused. Some economist will say that a human life is worth US$7.5 million (an estimate from 2020 by the US government); somebody else will reply that you can’t reduce a human life to money. Which is true in the sense that you can’t “sell” a human life for $7.5 million — but you can totally use American dollars as a unit of measurement for some practical purpose, which is all the US government was doing here. There is a confusion between the proxy and the real thing.

Everyone gets confused about money because everyone is obsessed with it. I do mean everyone. Rich people are obsessed with money. Poor people are obsessed with money. People in capitalist economies are obsessed; people in non-capitalist systems are obsessed just as much. People in hunter-gatherer societies that haven’t invented money aren’t, of course, but they’re obsessed with wealth anyway, and they’d become obsessed with money if it were introduced to them. The same is true of children; and then teenagers are obsessed with money, working adults are obsessed with money, retirees are obsessed with money, people on the brink of death are obsessed with the money they will pass on to their families. Billionaires and beggars, heads of state and beneficiaries of state welfare, right-wingers and left-wingers: everyone wants wealth, by definition, and therefore no one is able to keep a clear head when thinking about the proxy for wealth.

The result is that money, in addition to being weird, is so often extremely awkward.

And today I am stepping into the pool of awkwardness: I am turning on paid subscriptions for this blog.

To be clear, I feel very, very strange doing this.

I’m subscribed to some other Substack publications that eventually had the Today I Am Turning On Paid Subscription post, and although I’m totally on board with those writers making money from their writing, and although their announcements tend to be made in the most classy manner (for a great example, see Experimental History’s), there’s still a part of me that went “ugh” when I read those posts.

So why am I doing it? Partly because a few people I trust said I should, partly because I reached the symbolic 1,000 subscriber figure, partly because there doesn’t seem to be a downside with just activating them and letting people use it like a donation system. Well, no downside except for the awkwardness.

Another reason it that it seems worth getting used to the awkwardness. My guess is that almost everyone who sells something feels on some level that they shouldn’t — and yet they should. Activating paid subscription is a signal to myself that I should consider my writing as valuable, and price it accordingly.

For now, I don’t think I’ll change anything to the functioning of the newsletter, which means there aren’t really any strong reasons to pay. I’m not going to paywall future posts. At most I might lock some really old posts from the archive that I don’t necessarily endorse anymore. Later, perhaps there’ll be some extra content, but it’s not really worth putting my energy into this while there aren’t many people in the club. Maybe that can work as an incentive to get a paid subscription!

As another incentive, there’ll be a 20% off special offer for the month of March. Get it while you can! (Ugh, it feels so weird to create a “special offer.” I’m the world’s worst salesman, clearly.)

Please do not feel pressured to get a paid subscription. But if, by some weird stroke of fate, you do want to pay $5/month (or the discounted $50/year, or the double-discounted $40/year limited offer), for no clear immediate benefit except my gratitude, then you are now free to do so, and your support is greatly appreciated.

You’re a great writer, that’s value enough for your work! (she says while trying to remind herself the same thing....)

Congrats on 1,000 subscribers! And I love this post and the image of the plate money.