‘The Power of Myth’: A Book Review

AWM #66: On comparative mythology, pareidolia, and following your bliss 🗿

Joseph Campbell was a leading scholar of comparative mythology. Comparative mythology is the study of myths and religions across societies with the purpose of noticing commonalities in the human experience. Or maybe it is the art of finding cool tendencies in human cultures where none exist, thanks to our bias for pattern recognition. Frankly, after reading The Power of Myth, I couldn’t quite say which it is.

The Power of Myth is an unusual book. First, physically: it’s a large and cumbersome hardcover, more similar in its format to a textbook than a typical nonfiction book. Second, aesthetically: it’s a pure product of the late eighties, which shows in its characteristic typesetting and dubious color choices on the cover. Third, in its content: it introduces the breadth of Campbell’s scholarship not with regular prose, but with the transcript of several interviews between Campbell and journalist Bill Moyers at Skywalker Ranch (the home of Star Wars’s creator George Lucas). The interviews were broadcast on PBS in June 1988, the year after Campbell’s death. They were apparently hugely popular — you can watch them online if you google well enough — and they were released along with this companion book. A podcast transcript from before there were any podcasts.

The result is something perhaps more honest than most nonfiction, but also far less organized. The conversation meanders, jumps constantly from a topic to another, and is difficult to grasp in its totality (not that this would ever be possible with a subject matter as vast as “myth”). We might be talking about marriage on one page, growing from a child into an adult on the next, and then do a short bit about gangs and initiation rituals, immediately followed by thoughts on being a generalist vs. a specialist.

It took me a year to read this unwieldy book. It’s full of insights, most of which I have absorbed by osmosis over the course of reading it, meaning that I but can’t really write about them unless I reread the book (which I won’t). There are, however, two big topics that The Power of Myth etched into my mind: pareidolia and bliss.

Pareidolia

The central question of comparative mythology is, Why are there similarities between the myths of diverse cultures?

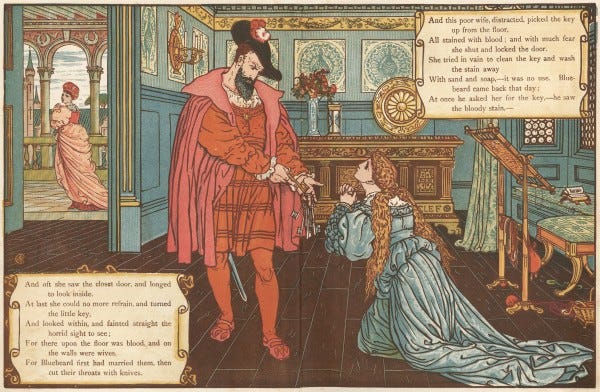

Consider, for instance, the motif of the One Forbidden Thing. In the Bible, God tells Adam and Eve not to eat the One Forbidden Fruit. In Greek myth, Pandora must not open the One Forbidden Box.1 In French folk tales, Bluebeard tells his wife to never enter the One Forbidden Room. How come there’s always a forbidden something, and how come it’s always a woman who eventually trespasses?

Campbell says there are two possibilities. The first is that across the world, the human mind works pretty much the same way.

The psyche is the inward experience of the human body, which is essentially the same in all human beings, with the same organs, the same instincts, the same impulses, the same conflicts, the same fears. Out of this common ground have come what Jung calls the archetypes, which are the common ideas of myths.

In other words, the myths of Eve, Pandora, and Bluebeard’s wife might be similar because they embed a universal lesson about curiosity and disobedience, especially, perhaps, in women. And this generalizes to myths from across the world. Dig long enough in the strata of culture, past the superficial layers of language and custom, and you’ll find that the people of Europe, Africa, Asia, America, and Oceania are all, deep down, the same creatures.

But of course, there’s the second possibility, which is what we call, in studies of cultural evolution, “horizontal transmission”:2 the diffusion of ideas and memes between cultures due to coexistence, trade, conquest, and prestige.

Campbell does mention diffusion, but I think he underplays it. Similarities are more fun when they point to a deep truth about the human psyche. It’s a bit boring to say that the curiosity of Bluebeard’s wife is simply a retelling of a common trope in medieval France that is ultimately inspired by the well-known myth of Pandora or by the Bible, as opposed to some insight about female psychology or whatever.

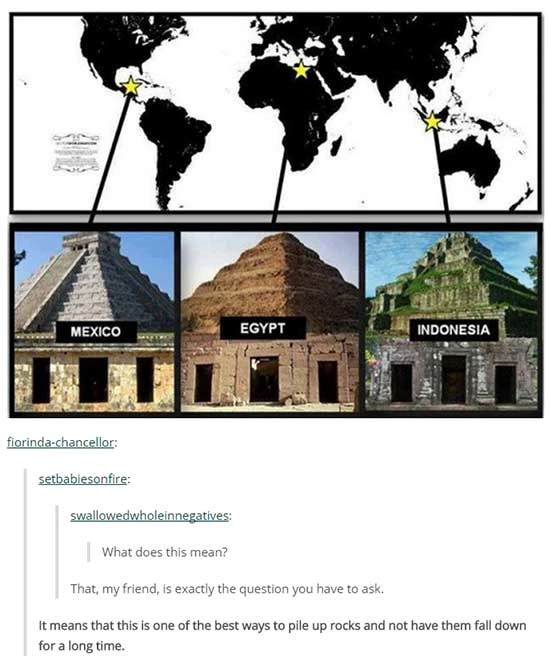

Besides, it was Campbell’s whole life work to examine those similarities, so I wouldn’t be surprised if some sort of expert bias came into play. Pareidolia is the documented human tendency to see patterns — especially faces — in what might actually just be a random arrangement of rocks, or a power outlet. When you read The Power of Myth with a skeptical eye, you begin noticing pareidolia a lot.

One example occurs when Campbell and Moyers discuss the circle. As a basic geometrical shape, the circle comes up all the time. The psychologist Jung has said it’s “one of the most powerful religious symbols,” “one of the great primordial images of mankind.” Campbell adds that “circular images reflect the psyche.” That the circle “represents totality.”

A common instance of circles in daily life is in rings. Moyers asks, what does the wedding ring symbolize?

That depends on how you understand marriage. The word “sym-bol” itself means two things put together. One person has one half, the other the other half, and then they come together. Recognition comes from putting the ring together, the completed circle.

What about the Ring of the Fisherman, worn by the Pope?

That particular ring is symbolic of Jesus calling the apostles, who were fishermen. . . . This is an old motif that is earlier than Christianity . . . an old idea of the metamorphosis of the fish into man. The fish nature is the crudest animal nature of our character, and the religious line is intended to pull you up out of that.

(A bit earlier, Campbell says that religio means “linking back”; circles can be seen as a representation of that connecting link.)

The monarch of England receives a ring when she or he is crowned; what does that mean?

There’s another aspect of the ring—it is a bondage. As a king, you are bound to a principle. You are living not simply your own way. You have been marked.

All of this is plausible. All of these interpretations seem correct enough. But I’m not sure that when you put them together — in addition to other interpretations of the circle as discussed by Campbell, like clocks, the cardinal points on a compass, magic circles drawn by wizards, the yearly cycle of seasons, the ancient Chinese and Aztecs placing their country at the center of a circle, mandalas as a representation of cosmic order, and more — they constitute evidence for some sort of grand truth about the souls of humans.

It might just be that circles are a basic geometrical shape. And that the only grand truth we can infer from rings is that human fingers are cylindrical.

It’s possible that I am primed against pareidolia more than most. One of my favorite books is Scott Alexander’s Unsong, an epic novel that exaggerates pattern recognition to an absurd degree in order to make fun of it. It’s great. Here’s an example from Chapter 1:

The timer read 4:33, which is the length of John Cage’s famous silent musical piece. 4:33 makes 273 seconds total. -273 is absolute zero in Celsius. John Cage’s piece is perfect silence; absolute zero is perfect stillness. In the year 273 AD, the two consuls of Rome were named Tacitus and Placidianus; “Tacitus” is Latin for “silence” and Placidianus is Latin for “stillness”. 273 is also the gematria of the Greek word eremon, which means “silent” or “still”. None of this is a coincidence because nothing is ever a coincidence.

Let’s be clear: These ARE coincidences! And when they’re not, it’s usually because they’re intentional references. In real life, it’s quite uncommon that there’s a deep hidden explanation. Sure, human psychology is complicated, and some of the patterns that Campbell identifies are plausible, but it’s difficult to separate them from all the pareidolia, not to mention the simple diffusion of ideas across cultures.

And it you don’t separate those, then you end up with a universe full of ludicrous kabbalistic correspondences, as in Unsong. How do you know what’s meaningful when you can find symbolic meaning in anything?

Of course, Campbell would probably have ready answers to my qualms, maybe in one of his many other books that I haven’t read. He might say that myth is not really about material reality in the first place. What matters is how we interpret the symbols to figure out our lives. And you know, I don’t disagree. It just feels a bit too postmodern to me. You don’t need to come up with ad hoc explanations of every symbol for comparative mythology to be interesting.

Bliss

I may have been critical of Campbell above, but pareidolia is the only shortcoming in what is otherwise an impressive book. The titular “power” of myth is recognizing patterns in our own lives so that we can live better — and on that, the book absolutely does deliver.

In particular, one idea that appears time and time again is that of following your bliss.

Campbell shares an anecdote of overhearing a family in a restaurant. The father is telling his son to drink his tomato juice. The son doesn’t want to. (Understandably so; this is tomato juice.) His mother says to the father, “Don’t make him do what he doesn’t want to do.” To which the father replies, “He can’t go through life doing what he wants to do. . . . Look at me. I’ve never done a thing I wanted to do in all my life.”

That’s a man, says Campbell, who never followed his bliss:

CAMPBELL: You may have success in life, but then just think of it—what kind of life was it? What good was it—you’ve never done the thing you wanted to do in all your life. I always tell my students, go where your body and soul want to go. When you have the feeling, then stay with it, and don’t let anyone throw you off.

MOYERS: What happens when you follow your bliss?

CAMPBELL: You come to bliss.

This is not unlike the cliché advice to “follow your passion.” But… it hits more powerfully, I find.

Campbell’s exhortations are part of a long tradition of warnings on what happens when we are not true to ourselves. I wrote about this, too, in my essay on building Rube Goldberg machines. I think, and Campbell would certainly agree, backed with the study of hundreds of mythologies, that it is one of the major problems of humanity. We have normalized not doing what we want to do. We have normalized doing what we don’t want to do.

In the Arthurian story of the Holy Grail, the land is said to have been laid waste. What is the wasteland? Campbell: “Is it a land where everybody is living an inauthentic life, doing as other people do , doing as you’re told, with no courage for your own life.”

Who escapes the wasteland? Artists. Poets. They are “those who have made a profession and a lifestyle of being in touch with their bliss.” Also, anyone who puts individual choice above the demands of society, like a career that you enjoy as opposed to what your parents want you to do, or romantic love as opposed to organized marriage. Campbell is pleasantly individualistic — an outlook on life that he attributes to the tales of love by the troubadours of Medieval Europe.

The best part of the Western tradition has included a recognition of and respect for the individual as a living entity. The function of the society is to cultivate the individual, It is not the function of the individual to support society.

Interestingly, mythology — which is far older than the troubadours or individualistic love — is more concerned with the functioning of society than with private matters. Myths arose as a way to explain the world and ensure social order. But love and sex are too powerful, too personal for them to fit well within social order. Collective myths aren’t great at handling those, although some of the more recent tales, since the time of the troubadours, have been providing an alternate frame.

Myths definitely have power, as the title of the book states. Their power comes from encoding the wisdom of the ages, from formulating lessons and explanations, from offering guidance. But it’s fine to reject them. Know them, yes, but don’t submit to a society and its mythology if you don’t want to. Campbell says again and again that to live truly, to live as an individual as opposed to a cog in a bigger machine, is worthwhile. Follow your bliss.

As in anything, following your bliss will go better if you do it with awareness. Thus I recommend reading The Power of Myth, if only to have a better idea of what hundreds of cultures have figured out in humanity’s never-ending quest to answer the fundamental questions, like “how to live well.”

Just be mindful of our strong tendency for pattern recognition (which might be a human universal? Are there myths about pareidolia, besides Unsong?), and you’ll be fine.

“Vertical transmission” is the spread of culture through heredity, and is kind of the default mechanism for mythology and religion, since the vast majority of people adopt the beliefs of their parents.