The Secret of Happiness Is That There Are Three Kinds

AWM #77: On the three flavors of the good life: hedonism, eudaimonia, and psychological richness 🍦

Everybody loves having a third option to get out of an annoying dichotomy.

You reject being labeled as either a leftist or a right-winger: you are, of course, an enlightened centrist. He doesn’t like the noise and density of the inner city, but the countryside is far from everything: so he chooses, of course, the suburbs. Philosophically, she doesn’t fully agree with either consequentialism or deontology: her ethical framework is, of course, virtue ethics.

I love third options just as much as anyone else. So imagine my pleasure when a 2021 paper identified a third option in the classic dichotomy between hedonism and eudaimonia: psychological richness. I don’t seek pure pleasure nor pure purpose; I seek, of course psychological richness.

What does that mean, you ask? Let’s backtrack a bit.

A traditional question in philosophy is, “What is the good life?” In what ways should you live to be able to say that your life is good? Traditionally, there have been two answers:

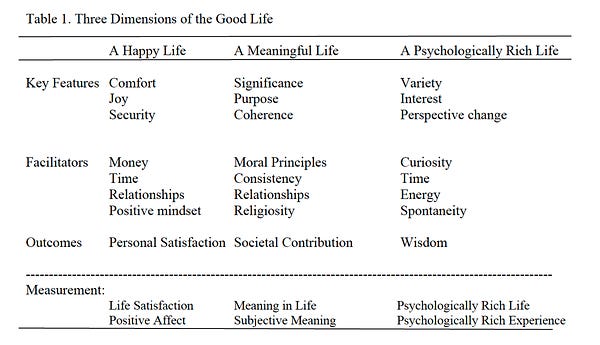

Hedonism is goodness that focusses on comfort, security, pleasure, and having money, time and fulfilling relationships. It can be summarized by the word “happy.”1 There are many ways to achieve a happy life, of course, but we can imagine things such as having a close-knit family, making a high salary at a job you like, and having the means to treat yourself to luxuries.

Eudaimonia is goodness that focusses on having a purpose, upholding moral principles, and contributing to society. It can be summarized with the word “meaningful.” There are many ways to find purpose, from volunteering in your local community to devoting your career to help the poor, write about ethics, or solve a technological problem.

While this dichotomy is conceptually useful, it doesn’t imply stark opposition. A life can be both happy and meaningful. But in practice, most people will aim for one or the other. And maximizing hedonism may make it difficult to reach eudaimonia, or vice-versa.

Now enters the third dimension:

Psychological richness is goodness that focusses on having interesting experiences, novelty, changes in perspective, and adventure. It can be summarized with the word … “psychologically rich” — yeah, we don’t really have ready-made vocabulary for it. Perhaps “diverse” would do it. There are many ways to have a diverse life, such as staying curious, travelling to new places often, meeting lots of people, and seeking unconventional experiences.

Again, nothing prevents a life from being happy, meaningful, and psychologically rich. In fact these things are often correlated — but not perfectly. Statistical analysis confirms that the three types are distinct. And if you ask people to choose one at the expense of the other two, you typically get a majority (50-65% depending on the country) who pick happy, and about a third who pick meaningful, but there’s always a significant minority (5-15%) who pick psychologically rich.

This tweet by one of the authors of the study, Erin Westgate, and the associated Twitter thread, provide a good summary.

This study is old news, from July last year. Yet it has remained on my mind for months. It seems to me that this is more than a mildly interesting bit of psychological research: it puts in words (and in math) a concept that I have never truly articulated, yet which made total sense as soon as I saw it.

For a long time I have known that I like to emphasize new experiences over many other things. In thinking about my own values, I have determined that diversity — whether biological, cultural, or other types — is something I consider important to a larger degree that other people do. I even wrote a whole series of essays on the topic!

In fact, my whole personality seems geared towards psychological richness. I’m endlessly curious, and I can nerd out about almost any topic; I even have trouble defining what I’m interested in (for example, in order to describe this newsletter) because there are too many things that could fit. I enjoy trying new foods. I’m more likely to pick an ice cream flavor that I’ve never tried than to pick one I know I like (which would be what a happiness-geared person would do). This quest for diversity has even been an obstacle to, for example, adopting vegetarianism. I know that you can eat well (happily) without meat; I care somewhat about the (meaningful) ethical implications; but eating a diverse diet, for me, trumps both of these concerns. A diet without meat is strictly less diverse than a diet with it, so to me it is inferior.

Just like people from various sexual or gender minorities feel a crashing wave of relief when they find out that there are other people like them, learning about this third kind of good life felt great. I felt seen. It gave massive justification to doing weird things (by society’s standards) like quitting my job and trying a whole bunch of projects since last year.

“The secret of happiness”2 is a trite phrase. It’s unlikely that there’s a hidden truth out there that will make you happy once you learn it. Plus, there’s plenty of scientific research on happiness; if a secret existed, we’d have learned it by now.

Yet it felt, to me, that this particular scientific research unearthed an actual “secret of happiness.” The secret is simply that there are three flavors.

There are several implications to the existence of three kinds of good life. One is about understanding people better.

For example, let’s go back to meat-eating. Suppose you’re a vegan activist trying to convince people to give up meat. You have convincing ethical arguments, and whoever hears you will be likely to agree that eating less meat would make them better people. However, changing a person’s behavior is harder than convincing them that you’re right. It depends, among other things, on which of the three types they belong to:

If they’re in the meaningful gang, you’re done. Upon learning from you that giving up meat would be purposeful, they quickly agree to make this one of their contributions to global welfare. Success!

If they’re instead in the happy gang, you might need to nudge them a bit more. For them, the good taste of meat is valuable, and changing their habits would be uncomfortable. They may be willing to sacrifice that, but it’ll be easier if you soften the blow. So you might tell them about good and easy vegetarian recipes to show them that they wouldn’t lose too much happiness.

But what if they’re in the psychologically rich gang? Then you need to convince them that giving up meat will not reduce the diversity of their diet. That may prove difficult — but it will be even more difficult if you haven’t read this post and are not aware that there are people geared toward psychological richness out there. And so you’ll get the weird result that some people agree that eating less meat is a good idea, and yet they still do it, because nobody thought of providing them with an alternative that suits them.

In other words, it’s important to recognize that people define “the good life” in different ways. Otherwise you won’t fully grasp what they want. And then whatever you’re trying to do — activism, politics, art, whatever — will fail.

This is, indeed, a retelling of the principle that awareness and empathy are at the root of everything good. The concept of psychological richness gives you an extra tool to understand people, without requiring a descent into the chaotic mess of personality traits — of which there are many more than three.

Another implication is that you should switch your focus between the three. Remember, the good life is never good in only a single dimension. In the original dichotomy, living a happy life without meaning is widely considered undesirable; and living a meaningful life without happiness is also bad. You want a balance. Adding a third dimension doesn’t change this.

Imagine a person who works a highly-paid job that truly improves the world, but has no hobbies and is always in the office: their life is happy and meaningful, but boring.

Imagine a person who’s wealthy, travels the world, has cool new experiences all the time, but doesn’t really have a purpose: their life is happy and psychologically rich, but meaningless.

Imagine a person who gets to perform their art in a variety of cities, but who is precarious in their finances and relationships: their life is meaningful and psychologically rich, but unhappy.

You want a balance.

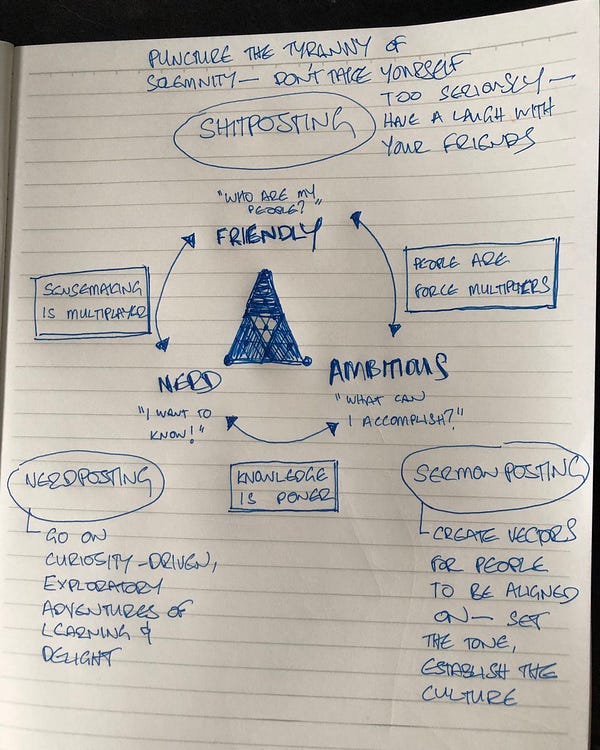

This reminds me of a similar frame by @visakanv according to which there exist people who are friendly ambitious nerds, embodying three qualities: the ability to develop relationships, the desire to accomplish things, and the drive to follow their curiosity. To draw parallels with our three flavors of good life, it seems correct to say that:

friendliness = happiness;

ambition = meaning;

being a nerd = psychological richness.

And indeed, in either case, lacking in one of the three dimensions will make you an imbalanced person. You want to strive for all three!

But of course, that’s exactly what a pro-psychological richness person like me would say, so make of that what you will.

A word like “happy” is imprecise and could apply to any kind of good life. In this post it refers to hedonism.

Okay I lied, I’m using “happiness” here to refer to the three kinds at once. Sorry!

similar to what I saw on twitter once. there are 4 types of people:

1. ascetic

2. hedonist

3. nhilist

4. creative

maybe psychological richness crowd is just creatives in their learning phase