The Unsolvable Puzzle of Modern Architecture

AWM #52: Why so much disliked modern architecture? And why is it so difficult to answer that question? 🏢

This is my 52nd weekly post — which means I have successfully written this newsletter without fail for one year! I’ve come a long way since my unassuming first post in November 2020. Hopefully, the redesign from last week gives me the steam needed to do this for another full year at least. I’m aiming for more important topics and higher quality writing than I’ve been doing so far. This seems possible now thanks to the writing experience I’ve gained over the past year.

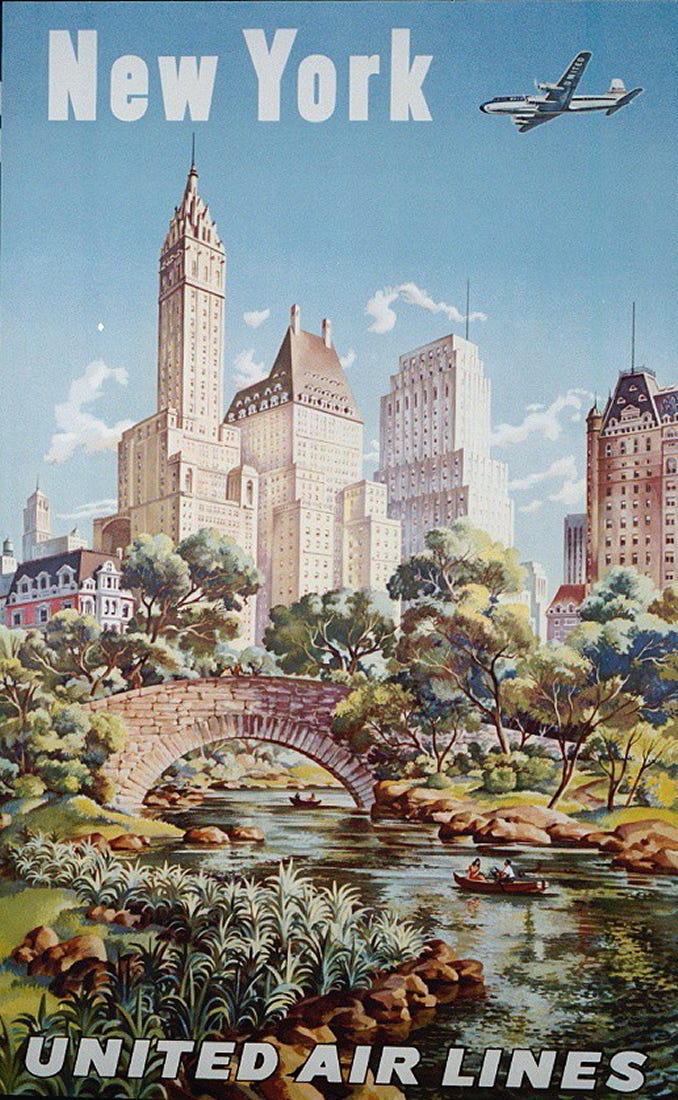

Not long ago I was visiting New York City, and one thing I enjoyed was looking at the old skyscrapers. A notable one is the San Remo, a twin-tower complex of luxury apartments on the west side of Central Park:

New York City is fairly unusual in that it was building skyscrapers1 earlier than any other city, except for a handful of other American cities like Chicago. This means that compared to your usual city, it has many more high-rises that were built before modernism took hold starting in the 1950s, with its clean lines, simple box shapes, and lack of ornamentation.

The most famous pre-modernist skyscrapers in NYC are the art deco Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, dating to the early 1930s — the same period as the San Remo above, although the latter is less art deco and more Renaissance with classical elements (like the Corinthian temples at the top). But there were many earlier skyscrapers, such as the Flatiron and the Metropolitan Life Insurance Tower.

My own city of Montreal, for example, has about one big art deco skyscraper and a few older, smaller high-rise buildings. But the city’s most rapid development phase was in the 1960s, and so most skyscrapers are modernist. The most famous might be Place Ville-Marie:

Later, the clean and boring shapes of modernism gave way to the slightly more adventurous styles of postmodernism, but still, most skyscrapers of the past 70 years look alike. They’re glass and metal, in varying shapes. Almost no one is building anything like the San Remo anywhere.2

Why not? This is a deep question. A puzzle. In fact, it’s a specific instance of the general puzzle of modern architecture, which can be framed in this way:

Most people don’t like modern architecture, or like it less than traditional or classical architecture. Yet we keep building modern architecture and very little classical architecture. Why?

There are… many explanations for this. Too many, in fact, for all of them to be correct. Yet they (almost) all seem at least plausible. Here’s a non-comprehensive list.

From Scott Alexander’s post Whither Tartaria?, which explores this question (including for other art forms than architecture), we get a bunch of incomplete and often contradictory hypotheses:

Rich people are subtler now than they used to. The beautiful, ornate architecture of the past came from kings and bishops and merchants showing off their wealth, but in recent times, such people prefer to hide their wealth. So they don’t pay for buildings that are externally beautiful anymore.

Rich people are out of touch with common people. The tastes of the elite have diverged from the masses, and elite people are more concerned with showing off to other elite people than to commoners. This is somewhat in opposition to the first explanation.

Random cultural changes have pushed us towards styles that value ornamentation less. The example in Scott’s post is going from Catholic to Protestant culture in parts of Europe, which is associated with austerity.

Modern architecture is actually better than traditional architecture in some deep sense, the same way a fine wine is “better” than a sugary soda, or listening to opera is “better” than watching reality TV, even though more people prefer the latter in all these cases.

Labor costs more, so we build simpler buildings now. Modern architecture is geometrically easier and has less ornamentation requiring intensive labor. This seems like a weird argument when the societies producing ornate architecture would have been far less wealthy than we are. Surely paying a stonemason for a lifetime of building a cathedral cost more, not less, to a medieval society than to modern society, relative to the total wealth of the time. Okay, most people today can’t justify the extra cost of adding a Corinthian temple at the top of their apartment building, but there’s no reason to think that people in past centuries could justify that cost any better.

Art and pop culture have diverged. Pop songs and superhero movies fulfill the common need for beauty, while modern poetry and experimental films fulfill the artistic need for experimentation and novelty. This is an argument for the tendencies of art in general and doesn’t really apply in an obvious way to architecture.

Rich people now prefer to signal taste than wealth. Thanks to the industrial revolution, there’s a lot of wealth going around, so the actual way to show you belong to the elite is to make tasteful choices. But this requires that things be difficult to categorize as tasteful or not. A modernist building that some people hate and other people love fulfills this condition.

(The title of Scott’s post refers to Tartaria, a fun conspiracy theory that says our world has suffered a catastrophic collapse in the early 20th century, and we’re simply not able to build beautiful architecture from the Tartarian golden age anymore. Technically this is possible…)

None of those explanations are sufficient, and some are probably downright incorrect, as Scott mentions several times. What else is there?

The software used to design buildings encourages uniformity. Seen in this Reddit comment on the Tartaria post. This is a pretty non-obvious explanation that seems very interesting to me, although it seems wrong that architects 100 years ago were less constrained in their tool use than they are today. Still, it’s possible that the domination of a few tools (Autodesk is described as a monopoly on engineering software) has an influence.

“Beautiful” has been done before, so architects focus on complexity and technical challenges. Mentioned and immediately demolished in this tweet from José Ricón Fernández. I also think it’s a poor explanation, partly because beauty is deeply linked to novelty. If you do complexity and technically challenging right, it will also be beautiful.

The vast majority of buildings are not designed by architects. Apparently the figure is 98% for American houses. As a result, there’s a lot of copy-pasting going on. This isn’t really an explanation, but suggests that the influence of professional architects is less big than we might think. It also hints at low-effort construction being very widespread. (Seen in this tweet from Sarah Constantin.)

Modernism and its descendants (post-modernism) are the only styles that fit for certain buildings, like skyscrapers. Skyscrapers are a special case because of their size and the fact that people enjoy large windows (which rules out constructing an Empire State Building or earlier high-rises again). Argument made here. I kind of disagree, it seems like this line of thinking is the result of lack of imagination.

There’s more focus in interior design than exterior design these days. Related to the “rich people are more subtle.” Tyler Cowen suggests here that it might because you don’t need to coordinate interiors, whereas exteriors have to match surrounding buildings. That seems plausible, but why is this happening now?

Overregulation. Cities now have all sorts of zoning requirements that disqualify many styles and techniques that architects could otherwise use. This does seem like a relatively new trend, so it could explain the transition from classical to modern.

Architecture isn’t supposed to be beautiful or make people feel good:

The philosophy of high modernism — top-down planning, science-inspired bureaucracies that tend to ignore the organic and complex reality of life — has done to architecture the same thing it’s done to governance, health, urbanism, and so on. In the 1950s and 60s, we surrendered beauty to technology, and haven’t recovered yet.

There are also some arguments I made in my essay arguing for a return of Greco-Roman architecture for the future:

Modern architecture seeks to showcase recent technological progress. Architects prefer to use new materials and techniques than to reuse existing ones. The idea of progress itself is fairly recent, hence the fact that modern architecture is a relatively new phenomenon.

Modern architecture is a form of atonement for the horrors of extreme nationalism and World War II. Scott suggests this in the Tartaria post, and so do I in the classical architecture post. This seems plausible, in part because non-Western countries seem to be building in old styles more often:

Bland modern architecture is politically safer, for the ideological reasons above and because today governments don’t want to be seen as wasteful. We’re back to the elite argument in explanation #1, with the added twist that we’re talking about public goods. It does seem like the way governments legitimize themselves has shifted over time.3

Going in a different direction, the premises of the puzzle might be incorrect. I don’t think the general idea is wrong (or I wouldn’t have written an entire post about it), but there are caveats that should be mentioned.

Old architecture looks nice because the nicest examples have survived. Modern architecture isn’t worse, it’s just more diverse in quality; in a few centuries the worst of it will be gone. I think a selection effect like this is definitely happening, but I don’t think it’s strong enough to dismiss the fact that many people do feel that modern architecture is bad.

We still build classical architecture, it’s just a smaller fraction of the total, since our culture is richer and more diverse now. It’s also less impressive and novel than it used to be. (Argument made in more detail in this response to Scott’s post.)

Most people don’t care. Few people hate modern architecture enough to do anything about it. Left to their own devices, architects try new things that they like in their tiny subcultures, and most people just accept this. Only a small population of weirdos like me get annoyed.

Okay. That’s a lot, actually. I wasn’t expecting this post to become an encyclopedic listing of all the takes on modern architecture. Not that this is all the takes. I honestly could have kept going — there are a lot of arguments floating around, and I haven’t yet reached the point where they get redundant.

The puzzle of modern architecture is fascinating. But equally fascinating is the meta-puzzle: why is this puzzle so difficult to solve? Modern architecture isn’t some super complicated hidden phenomenon in the natural world. It’s just the actions of humans in the past few decades.

Well, yes, the actions of humans over several decades can be enormously complicated. But still. It’s weird that this is a puzzle at all. Why have aesthetic preferences evolved in such a way that a lot of people are unhappy with what society is doing? Why is there a strong perception of things have gone worse even as we have become wealthier?

Possibly this is a consequence of the increased complexity of the world. In olden times, there was a small rich elite and the poor masses; there wasn’t enough space for the wealthy to develop many competing ways of showing their status. Now, instead, we have thousands of subcultures, and millions of ways to develop taste. Relatedly, there are now more forms of art and, within each form of art, more styles to choose from. We have all the past architectural styles, plus whatever we invent now. As a result, it’s impossible for our complex society to agree all the time on what is beautiful. So we get a lot of architecture that some people like and others dislike — modulated by effects such as elite tastes from explanations (1) and (2).

If this is true, it suggests that… the problem might get worse over time. In a way, it’s similar to politics. In a small tribe of thirty people, it isn’t hard for everyone agree on the best decisions; when the tribe grows to a country of millions, then you have a lot of competing interests, and whatever the central government decides is going to make a lot of people unhappy.

As new architectural styles get invented, perhaps there’ll be less and less agreement over what is beautiful. Or, even, on whether architecture should be beautiful at all. Some groups — starchitects, and whoever gives out the Pritzker Prize — prefer one kind of architecture, one that tends to be asymmetrical and grey and technologically impressive.

Some others, for instance whoever follows Wrath of Gnon on Twitter or would live in Poundbury, England, prefer another kind of architecture that follows more traditional principles.

Then there are lots of other groups with various other preferences, and of course a big group of people who just don’t care.

Is the puzzle of modern architecture a natural consequence of our developing civilization? Is it unavoidable? Maybe. But it still seems worth trying to solve, if we can. So which of the explanations above can we rule out?

For a broad definition of “skyscraper.” The word’s meaning changed gradually as taller and taller buildings were constructed. In the late 19th century, a 10-story building would have been unusually tall and called a skyscraper, but 10 stories is obviously less impressive today.

At least in the West. These posts on architecture almost always focus on the West, because other civilizations are doing different things. The 2012 Abraj Al Bair complex in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, seems superficially similar to the San Remo, for example.

See also this essay that compares society to ecology. The elites are similar to the major organism in an ecosystem, like an oak tree of apex predator, outputting wealth from which smaller organisms create their own niches.

What about how big buildings are financed? In contrast to the singular visions of wealthy people making unilateral decisions about taste, now we have committees of overeducated people whittling down novelty into blandness, "oh we can't afford bas relief window treatments since we're already over cost on foundations". Same thing in zoning approvals and public "art": least offensive proposals survive inertia-heavy committees.