The Value of Variety: Biodiversity

In this first instalment of a series of posts, we examine how biodiversity gets valued from economic and aesthetic points of view 🪲

Greetings!

This is issue #27 of Light Gray Matters and it’s coming to you from sunny and warm Montreal. Please do not hesitate to subscribe to get your own piece of sun every Wednesday:

After a break last week, I now return to the topic of variety (a.k.a. diversity). In Light Gray Matters #21 to 25, we covered several fundamental ideas:

Diversity is itself very diverse, since it can exist along many dimensions for all sorts of things.

All things exist at multiple levels of abstraction. They can be diverse at one level and not at another.

There are several (sometimes contradictory) ways to measure diversity.

The opposite of diversity is uniformity and can be desirable too, depending on context.

Diversity is associated with novelty, surprise, new information; uniformity is associated with comfort, stability, predictiveness.

What I want to do now is dive deeper into several kinds of variety. For the next few weeks, I’ll pick one type of thing at a time — e.g. living beings, human cultures, ethnicities (maaaaaybe) — and examine the value of variety for that thing.

Let’s start with one of the things I know best: biodiversity.

As we saw in the Pokémon post, measuring biodiversity is tricky. To simplify, let’s just consider the number of species as conventionally defined by biologists. How many species exist?

The answer is, as of 2021, between 8.0 and 8.7 million species.1

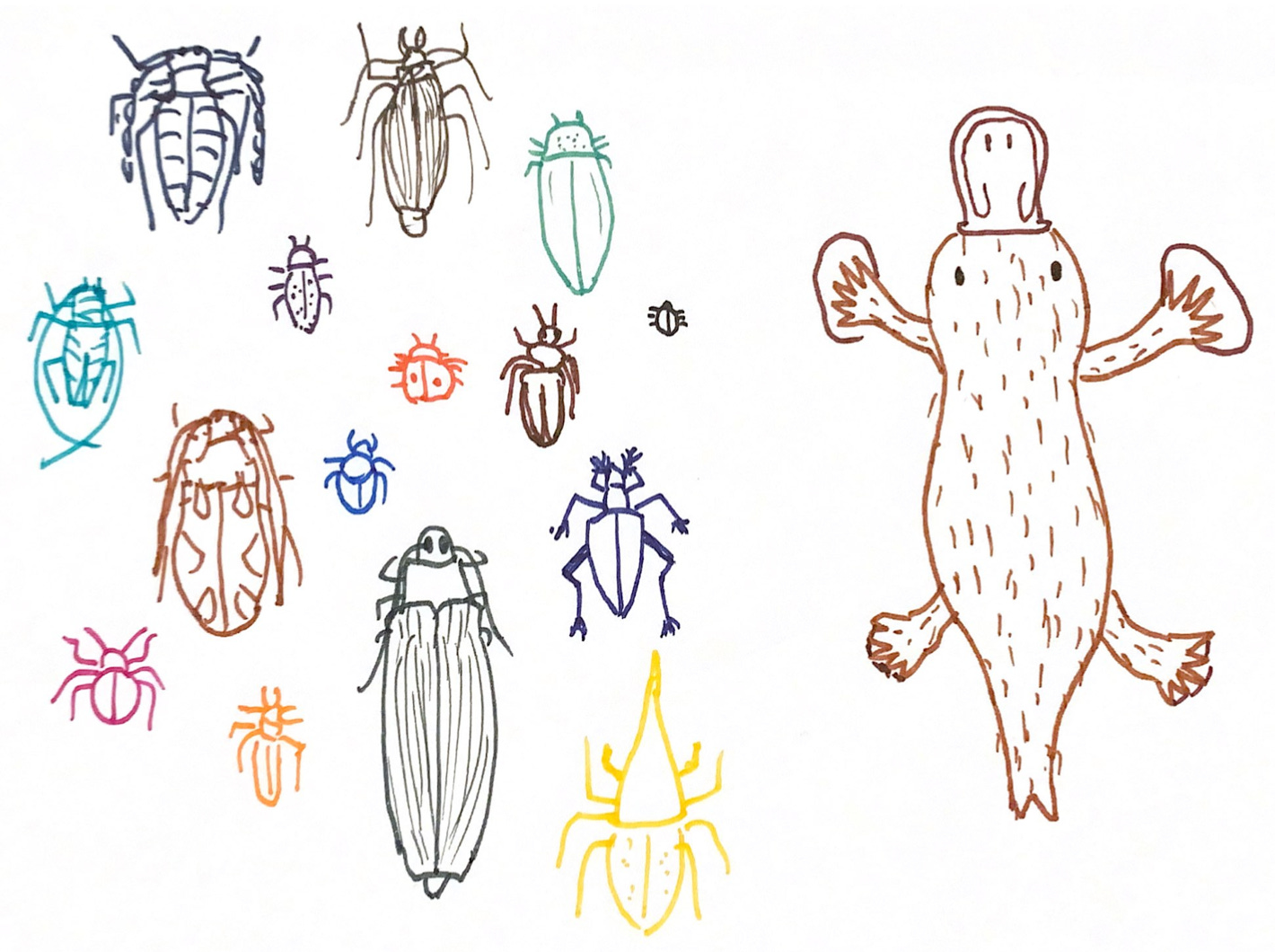

Note that there is variety in the diversity of groups themselves. Among all eukaryotes (everything that isn’t bacteria or archaea), insects represent between 50% and 80% of all species. A big chunk of that is beetles, who constitute “40% of described insects and 25% of all known animal life-forms” according to the beetle Wikipedia page. Meanwhile, there’s only one species of platypus, and nothing else that’s very closely related to it.2

Evolution tells us species aren’t fixed. Indeed, species are created all the time, although the process (called speciation) is slow. And species go extinct all the time. They seem to go extinct quite quickly at the moment, probably because of humans. As a result, many people worry about biodiversity loss.

Are they right? How important is biodiversity?

This isn’t a trivial question. On the surface, it sounds easy: “Of course biodiversity is important!” But think about it. Deep down, would you care if a single beetle species disappeared? If half of the beetle species disappeared?

What if we were talking about cockroaches? Or one of those weird worms from the deep sea? Or some ugly toad from a country you’ve never been to and never will?

People working in conservation have a much harder time getting funding and popular support to save “uncool” species, such as, say, sharks. Well, I think sharks are cool, but you see what I mean. Sharks are scary. A bit alien-looking. They don’t make great pets; they aren’t economically that important. So people don’t give a lot of money to save endangered shark species. (ADDENDUM: A friend who works in conservation points out that there’s a actually a lot of conservation money for sharks. I should have looked this up. Yeah. But my point still stands even if the specifics are wrong.)

And sharks are still pretty cool compared to most life out there. Nobody cares about the weird creatures that lurk in the deep sea, for instance. As goes a New Yorker cartoon: “I don’t know why I don’t care about the bottom of the ocean, but I don’t.”

Instead, the money goes to the cooler kids. Often that means cute large mammals like pandas, whales, or elephants. Birds, like eagles and condors. Beautiful predators like tigers and wolves. Species that provide something economically relevant also get a lot of attention: commercially exploited fish, trees, etc.

This suggests that we care about saving species from extinction mostly due to their inherent value (whether symbolic of economic) rather than their contribution to biodiversity.

So is biodiversity valuable at all, in itself, regardless of the properties of the species involved?

One of the main arguments to protect biodiversity is that it’s necessary for proper ecosystem functioning. One way diversity achieves that is by providing redundancy. Imagine a forest with a balanced mix of several species of trees, including ash trees, and another forest that’s 99% ash trees. Now comes along one of our beetle friends, the emerald ash borer. It kills all the ash trees. The first forest is fine, because there are many other types of trees. The second forest, meanwhile, is all gone.

Functioning ecosystems are really important. Like, several trillion dollars’ worth of important. In the US, the value of pollination by wild pollinators (such as bees, bats, birds, butterflies, and, yes, beetles) is estimated to be around $4-6 billion. Maybe it’s not such a big deal if some pollinator species go extinct, but if it the loss of diversity triggers a bigger upheaval and disrupts pollination in general, that could be catastrophic for humanity’s ability to feed itself.

So there are utilitarian reasons to care about biodiversity. And yet…

Back when I was a biology student, I took a few courses in biodiversity, conservation and the like. I got the impression that conservation biologists talk about the value of ecosystem services because that’s the best way to get convince other people (who don’t care that much) to give them funding. But deep down, they care. They want to protect biodiversity for its own sake.

Why? Because when they were kids, they read picture books with animals in it. Lots of animals. Tiny, shiny beetles. Gigantic sharks. Platypuses. Weird hoofed mammals with long necks from Africa. Slow reptiles that somehow carry a protective shell everywhere they go and live 150 years. Dinosaurs. All sorts of dinosaurs. Three-horned herbivore dinosaurs and big predator dinosaurs with minuscule arms and nimble and swift chicken-size dinosaurs and so on and so forth ad infinitum.

Biologists are biased, of course. They study life. So of course they like it. Of course they think it’s beautiful. Of course they think it’s grand.

I wouldn’t blame anyone for not caring as much as they could about biodiversity. But I do think it’s worth caring about. Each species, even the ugliest, makes the world a bit more interesting. The cool kids like the tiger and the bald eagle are cooler, sure. But even though they’re the stars of the movie of life, there’s a whole supporting cast that’s there and makes the whole richer.

I am an ex-biologist, after all. Of course I think life is grand.

Which is the more convincing argument?

That biodiversity is valuable because it provides us with pollinators and robust ecosystems and plants that we can develop medicines from and tourism to see charismatic large mammals?

Or that it is valuable for its own sake, because living beings are beautiful and interesting and full of colors and shapes and behaviors and they show how wonderful and creative nature can be (or God, if you are so inclined)?

It seems to me that both the economic and the aesthetic arguments are important, but I’m interested in discovering to what extent, depending on the context and the person. I suspect that these two opposite poles will crop up in pretty much all of my upcoming Value of Variety essays. Perhaps after a few weeks we’ll be better able to untangle them.

Meanwhile I remain

Yours in thinking about the grandness of things,

Étienne

P.S. Share this with all your biodiversity loving friends:

Only a small fraction of which, perhaps 14%, has been described by science.

Except for four species of echidnas. Together, platypuses and echidnas comprise the entire monotreme group of mammals, which are evolutionarily distinct from all other (marsupial and placental) mammals. One of their characteristics is that they lay eggs.

By the way. I once wrote a term paper on monotremes and got a grade of 100%. Still quite proud to this day.