The Value of Variety: Culture and Language

Instrumental and intrinsic reasons to like cultural diversity 🗣

Hi!

Welcome to Light Gray Matters #28, coming to you after a not-at-all frustrating half hour spent trying to repair my computer’s stuck spacebar and panicking because I wondered if I could write at all tonight. 🙂

The spacebar is now unstuck (sort of), and so the Value of Variety series can continue! Today we explore the value of cultural and linguistic diversity.

Last week, in conclusion to my post on the value of biodiversity, I wrote that there were two big classes of arguments to ascribe value to variety. There’s the economic argument: variety is useful, it leads to better outcomes, it’s less risky than uniformity. Then there’s the aesthetic argument: variety is beautiful, it makes the world more interesting, it’s less boring than uniformity.

We could also phrase these in terms of instrumental and intrinsic value: either variety is good as a means to attain something else, or it is good for its own sake. Or, realistically, a mix of both.

Let’s use these two angles to examine another type of variety: cultural and linguistic diversity.

I’m mixing culture and language in a single newsletter because they so often go hand in hand. Of course, several cultures can coexist within a single language group: thus the British, Irish, Americans, English Canadians, Australians, etc. are distinct cultures that all speak English. (Or so they all claim.) And several languages can be spoken within a group that is considered as one culture: all of Western Civilization can be seen as a single culture, at least at some level, yet Western Civilization exists in many tongues. In culture as in language, there are almost never any precise boundaries.

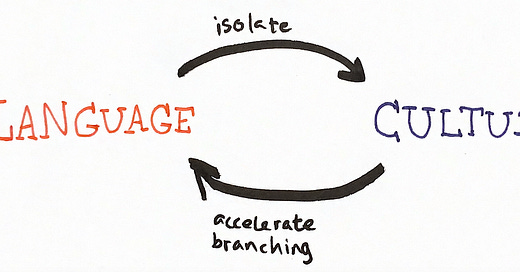

Yet language and culture are closely intertwined. Both new languages and new cultures arise continuously, usually due to some sort of separation — for instance geographic (e.g. the US vs. the UK), generational (boomers and millenials and zoomers talk a slightly different language1), or organizational (different companies have different work cultures). But crucially, they also reinforce each other in a feedback loop.

When two dialects get different enough due to some other type of barrier (say, an ocean), this creates a communication barrier and reinforces the separation. The two diverging cultures can then develop on their own; the world becomes more diverse. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that it is the cultures that diverge first, and that leads to the emergence of new dialects and languages? Who knows. Culture and language are siamese twins. We can’t ever truly separate them from one another.

Take Haiti. It is mostly populated by the descendants of African slaves brought there by the French. Haitians now mostly speak a language, Haitian Creole, that branched off of French and incorporates African elements. They also have a very different culture from that of France. It’s not clear which came first: did the organization of colonial society give the black slaves their own culture distinct from the white masters, leading to the emergence of a dialect, whose distinctiveness with French reinforced black culture, which reinforced the language, and so on? Or did their African mother tongues set them apart from the get go, and their distinct culture arose as a result of that? It doesn’t ultimately matter. Haitian culture and language helped each other thrive, and the result is a more diverse world.

But cultural and linguistic diversity can also be lost.

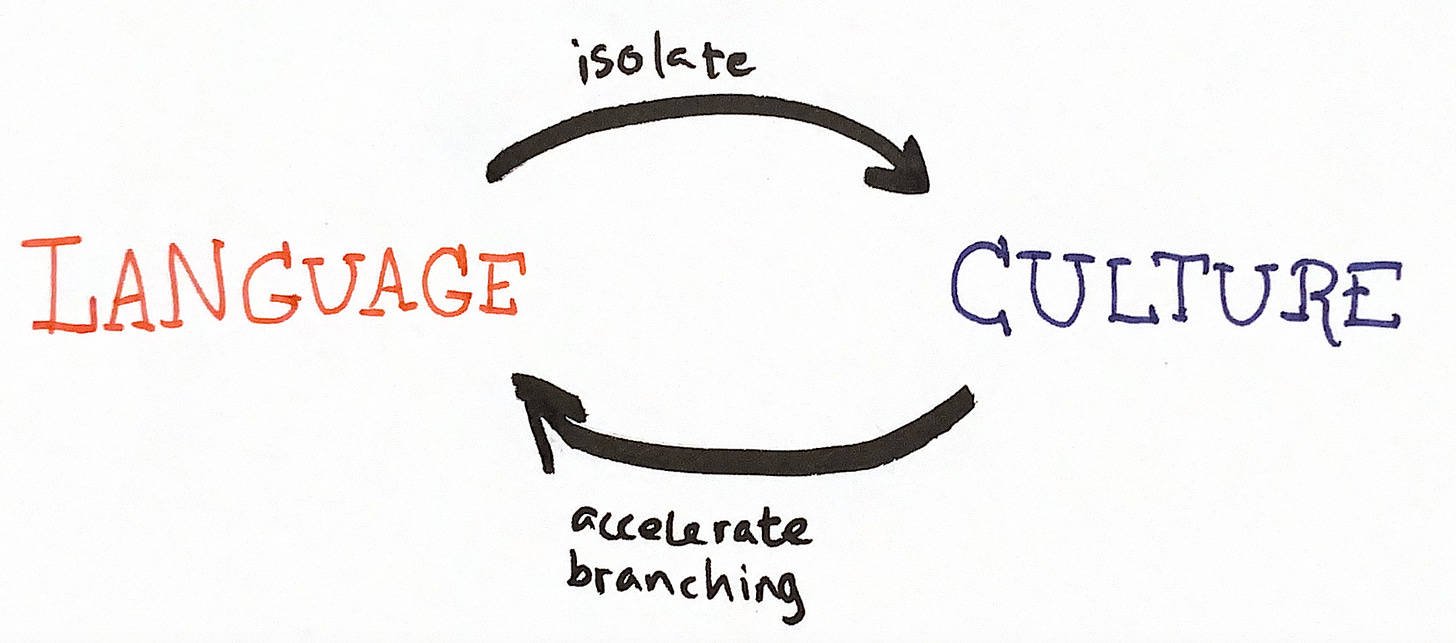

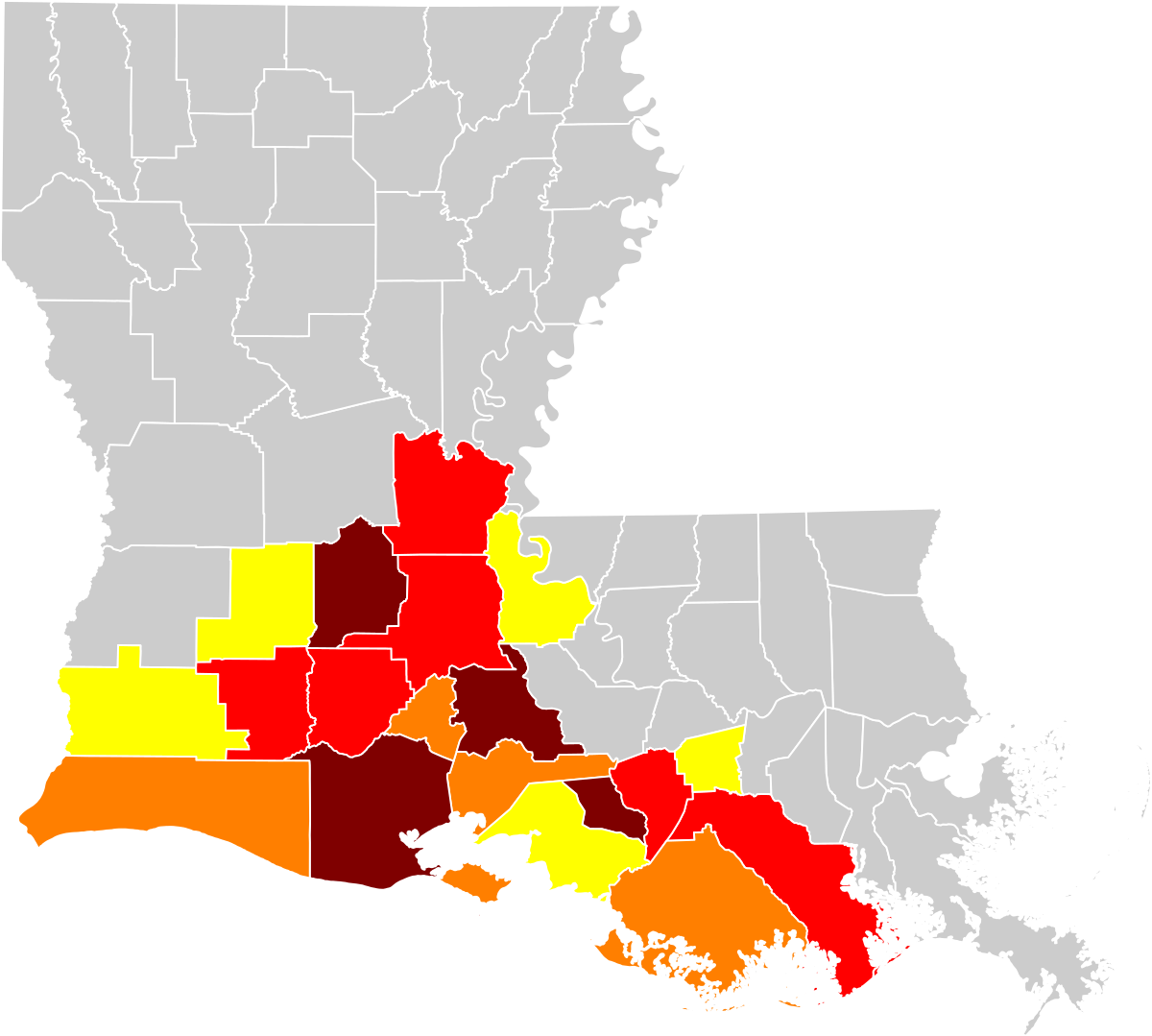

There are anywhere between 6,000 to 7,000 living languages. Most are spoken by less than 10,000 people. The current consensus is that between 50 and 90% of those several thousand languages will go extinct by the end of the 21st century. There are many reasons that a language stops being spoken, including the death of its speakers through genocide or natural disaster, which of course also come with the disappearance of their culture. But most commonly, language loss is due to cultural and economic pressure. If you’re a member of the French-speaking minority in English-majority Louisiana, it simply makes your life easier to speak English. So you do. And now, a couple of centuries after Louisiana became part of a mostly English-speaking nation, there barely are any Louisiana French speakers left.

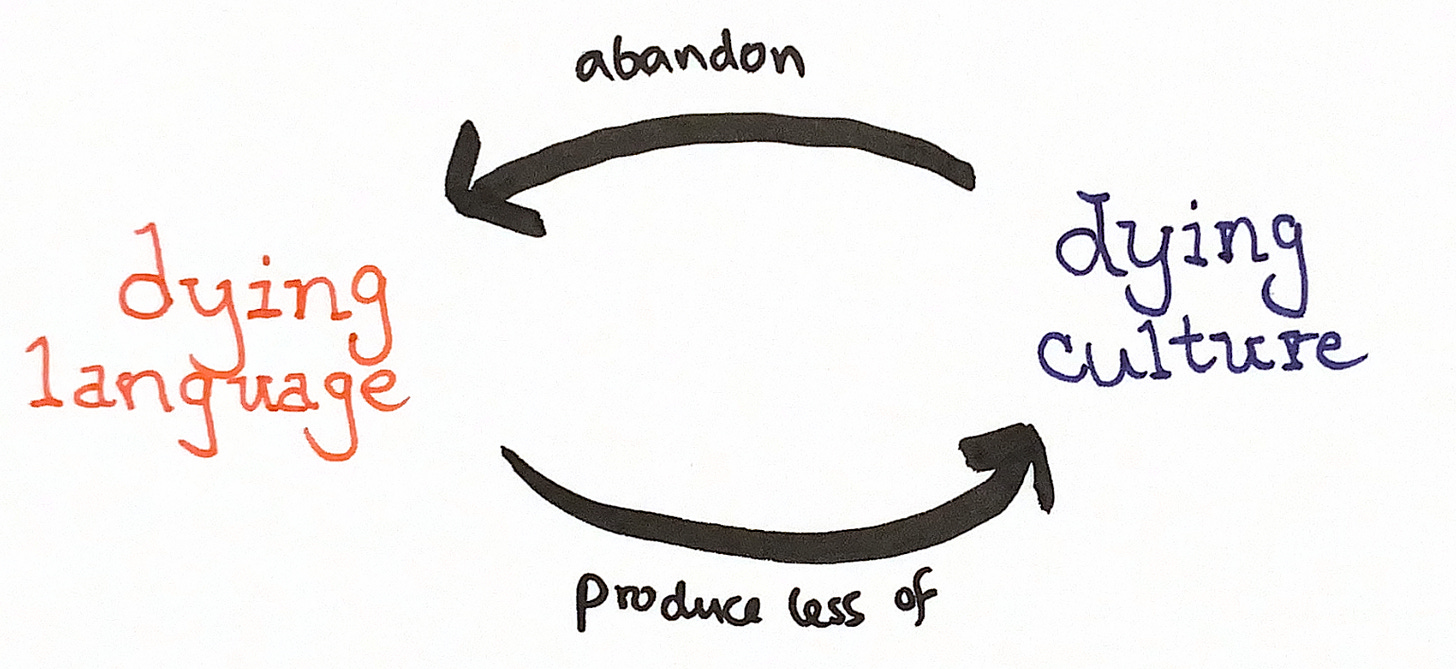

The loss of a language doesn’t necessarily mean the death of a culture. Louisiana still has its distinct identity. But the feedback loop works both ways.

As the speakers of an endangered language adopt a more influential language, their culture will look more and more like the culture associated with that stronger language. Thus many indigenous peoples in the Americas, most of whom have adopted European languages like English, French, or Spanish, are now far more culturally similar to their neighbors of European descent than they used to be.

And as the members of a culture undergo more and more influence from a more powerful culture, they will be more and more drawn to the language associated with that culture. Thus many people from non-English-speaking countries now work, make art, and live in English.

Should we be sad, when a language goes extinct? When a culture disappears?

In other words, is cultural diversity valuable?

Let’s make the case that it isn’t, briefly: Culture is human-made, not something mysterious we inherited from nature. It is continuously created, so there can’t be a shortage of it. It can be documented and resurrected if needed (unlike living things). Language diversity makes communication harder. We devote a lot of resources to learning languages and cultural contexts that we could spend on more useful things.

All right. This isn’t necessarily the strongest take, but at least I’ve mentioned some of the arguments. Now let me defend my actual case — that diversity is very precious, both from an economic and aesthetic perspective.

The economic case for cultural diversity

Is an abundance of cultures and languages good as a means for anything?

Consider 50 scientists working on a problem. The scientists all speak English and grew up in the same country, which is great, because it allows them to collaborate. But they also copy each other a lot. And at some point, they get stuck. They can’t think of any new methods to solve their problem.

Now imagine those 50 scientists are divided in two equal groups, one that speaks only English and one that speaks, say, only Greek. The two groups can communicate by hiring translators, but that’s low bandwidth. Most of the time, they’re insulated from each other. Now maybe the English-speaking group gets stuck, but the Greek-speaking group, doing its own thing, doesn’t. They solve the problem, translate the solution for the Anglophones, and everybody’s happy.2

The advantages of scientists being able to communicate with a lingua franca like English are obvious. But it comes with a danger: groupthink. A monoculture can get stuck with some traits — values, behaviors, styles — that aren’t optimal. In the absence of other cultures to try different ways of life, we may not even know what we’re missing.

The stereotypical story of a Westerner getting into Buddhism or other Eastern religious/philosophical traditions is an illustration of the instrumental value of cultural diversity. Maybe those traditions won’t give you better answers. But at least they allow you to search.

I think that’s the main instrumental advantage to cultural diversity. I can’t think of any other obvious ones, so let’s move on to the intrinsic value bit.

The aesthetic case for cultural diversity

Do you like to travel to exotic countries? Do you think foreign languages are beautiful? Do you enjoy cuisines other than your own?

If you answered “yes” to any of these questions, it is my pleasure to inform you that you like cultural diversity for its own sake!

And I truly think we do, most of us. Not everyone agrees that cultural diversity is always worth preserving, or that the costs it creates outweigh the downsides. But I think it’s pretty intuitive that having a variety of artistic traditions and architecture styles and recipes and ways of speech and so on and so forth is a good thing.

After all, we often seek novelty. And what creates more novelty than tapping into a big reservoir of culture we haven’t experienced at all yet?

Honestly, I was expecting this section to be longer than the previous one, but I guess I’ve made my case already. It’s pretty obvious, I guess. A more in-depth essay could carefully weigh the costs and benefits of cultural diversity vs. uniformity, but this is not it.

Also, I’m tired, and my keyboard spacebar troubles give me a convenient excuse.

So let’s stop here for now. We’ll resume next week with (if I’m feeling game) biology-related human diversity: race, sex, gender, and the like. Or maybe I’ll go the easy route and talk about diversity in abstract concepts like morals and finance. We’ll see!

Until then, I remain

Yours in trying to think of something to be yours in,

Étienne

So do Gen X, sorry for forgetting you when I first wrote that sentence

I can’t find it anymore, but years ago I read that some top math research institute in France was still publishing its discoveries in French, contrary to everyone else in the hard sciences. I believe it was claimed that working in French was one of the reasons they made so many new contributions.