The Value of Variety: Politics

Political diversity is unfortunately infuriating, but quite valuable 👑

Hello!

This is issue #32 of Light Gray Matters. We’re getting close to the end of my “value of variety” series; after today, I expect to write one more, next week, about diversity of thought and morality. Then I’ll let the matter rest and go back to posting about the most random topics.

But for today, a meaty topic: diversity in the context of politics.

Political diversity at the global scale

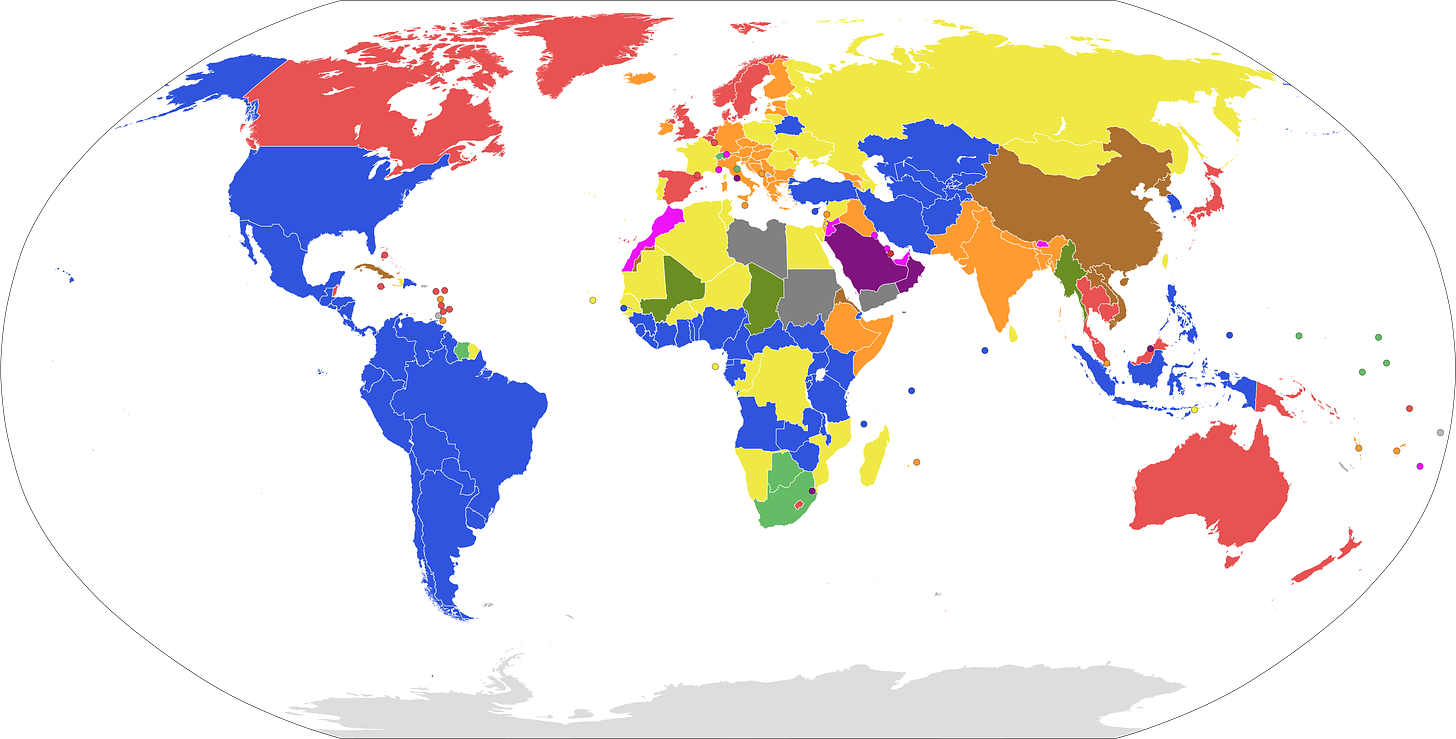

As I tweeted a long time ago, back when I had about 30 Twitter followers, the world is a political rainbow.

This map (from here) describes the forms of governments around the world. Blue, yellow, orange and pale green are various types of republics. Red, pink and purple are monarchies, ranging from constitutional to absolute. Brown means a one-party state. Gray and olive green are transitional and military governments.

This is a very superficial classification, depending mostly on how the head of state is selected (heredity, election, other) and how much power they have (absolute power to almost none at all, in the case of a constitutional monarch or ceremonial president). But then there are a thousand nuances we can add: Is there a parliament? How does it work? Does it have one or two chambers (or three)? How are its members chosen? How long do they serve? Are there political parties? How many? Is there a head of government distinct from the head of state? Is there a constitution? What does it look like? How are the executive, legislative and judicial branches divided? Are they divided? And so on.

We won’t get into the details of designing a political system — that sounds super complicated and better left to political scientists or whichever kind of person has what it takes to be a Founding Father. But let us note that the designs are super diverse. We have, among other oddities:

a tiny principality co-headed by a bishop in a neighboring country and the president of the other neighboring country (Andorra)

an elective monarchy whose king is a rotating position among a group of nine sub-rulers (Malaysia)

exactly one country ruled by an Emperor (Japan, down from three in the 1970s, when Ethiopia and Iran also had emperors)

a country with three capitals, a judicial one, a legislative one and an executive one (South Africa)

sixteen independent countries all ruled by the same woman (Antigua and Barbuda, Australia, the Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Canada, Grenada, Jamaica, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, and the United Kingdom)

Is there value in having a such diversity of political systems around the world?

It may be tempting to answer no — it’d be better to simply adopt the best political system everywhere. But then the question becomes: what is the best political system?

Constitutional monarchies like the UK, Canada, or Japan have been pretty successful countries by most standards. Does that mean everyone should have a constitutional monarch? Well, republics with a strong elected head of state have their own track record of success too, most notably, in recent history, the United States. And then there are the republics like Germany, with a ceremonial president who’s kind of like a monarch, except elected. OK, but all of those are democracies. Democracy is better than authoritarian regimes, right? Well, I think so, but Saudi Arabia’s been doing pretty well for itself with its absolute monarchs. So has China’s one-party system, for that matter. As someone with fairly standard Western liberal values, I’m pretty confident that China and Saudi Arabia’s governments aren’t great, but I suppose a lot of Chinese and Saudis wouldn’t agree with me. Plus, we could name countries that are in political turmoil for pretty much all of the above forms of governments.

“What political system is the best” is a question rife with uncertainty, influenced by personal values, and subject to political debate. Even if the population of a country were to agree on something (spoiler alert: that never happens), the next country might not. And even if the entire world agreed on some political system, they might still get it wrong.

The (instrumental) value of diversity in political systems is that the world, collectively, is trying a bunch of different methods. The rainbow is an experiment. There’s a lot of value in that — countries can copy what works elsewhere, or avoid what doesn’t work.

It’s thought that the city-states of Ancient Greece were successful for this reason: not united in a single polity, they could try different things (sometimes flatly bizarre, as in Sparta), which led to a golden age of science, art, and philosophy, and basically founding Western civilization.

(There aren’t very many city-states around today, but the main example, Singapore, happens to be doing pretty well.)

Of course, political diversity means that sometimes the people of a country may have it tough. North Korea seems to be a good example of how not to run a country. The rest of the world can therefore learn from the experience, but this is little consolation for the North Koreans who suffer from hunger, economic hardship, or downright oppression. I would prefer that a regime like North Korea’s didn’t exist — there’s no point to increasing political diversity by coming up with all sorts of stupid government systems that make life hard for people — but if it does exist, our knowledge of how the world works at least gets a bit richer.

And then there’s the aesthetic value. It’s kind of cool to have some queens and kings and an emperor alongside presidents and prime ministers. It’s interesting to compare political traditions and institutions. I wouldn’t say the aesthetic argument is very strong, but it’s there.

Political diversity at smaller scales

The question “What political system is best?” is only one of many political questions that can cause things on the scale from “mild disagreement” to “heated debate” to “flame war” to “actual war.”

There are tons of decisions human societies must make all the time, from what to do with taxes to how to punish crime to what species of endangered fish should we protect. That’s what politics is: decisions about the good of the collective.

Holding a political opinion means knowing the answer to one of those questions. It’s all good and fun until you meet someone who has a different answer. You’re obviously right and they’re wrong, but the problem is, for them, they’re obviously right and you’re wrong.

This is political diversity. It’s usually infuriating.

And yet it’s valuable! Because, as with political regimes, you can never be sure that your opinions are correct. I mean, yes, of course you’re sure they’re correct, but you’re actually wrong about that. It’s a simple mathematical truth: everyone has opinions that they’re certain about, but which will turn out, as society evolves, to be completely wrong.

The way to deal with that is epistemic humility — accepting that you don’t know much and will get a lot of things wrong. Epistemic humility is really hard, probably out of reach for most people, and the next best thing is accepting and embracing political diversity.

What does political diversity, at the scale of national or local politics, mean in practice?

It means pluralism — having different parties, competing for attention and votes, and defending different ideas. The more parties, the more diverse a political situation.

It means free speech — allowing ideas to be expressed openly, even the weird or distasteful ones.

It means decentralization — not having a single person or group decide everything, and giving local groups the capacity to take decisions.

There are, of course, exceptions. In a democracy, a party that would promise to cancel free speech or disallow other parties shouldn’t be allowed, because it would reduce future diversity, possibly in a disastrous way. As in anything, we don’t want to maximize diversity at the expense of everything else.

But by default, political diversity is good, even if it is annoying. It is good in the same way that the existence of mutations in biology is good, even if, individually, most mutations are harmful. Without mutations, there would be no evolution, and life as we know it couldn’t exist at all.

So political diversity means that sometimes (often), you’ll need to deal with people whose opinions sound horrible to you. It is infuriating, but it’s the only way the system as a whole can improve over time. Political diversity is the way to political progress.

Yours in hoping I don’t get too many political positions wrong,

Étienne

This is the basic thesis of multipartisan parliaments, and how American-style binary politics is bad. Unfortunately it is known that the EU might not be parity to its population regarding beliefs, and that diversity of within-party differences are still worth exploring.