Things I Learned From Ranking 1000 Historical Rulers

History ends up feeling repetitive when you look at all of it superficially 🫅

One of my obscure hobbies is contributing to a fan-made mod of a computer game that came out in 2005. The game is Civilization IV, and the mod is designed to simulate history more closely than the base game does. It is not my project, but sometimes I make modest contributions to the community in the form of historical research.

(By “historical research” I mostly mean, of course, digging into the Wikipedia mines.)

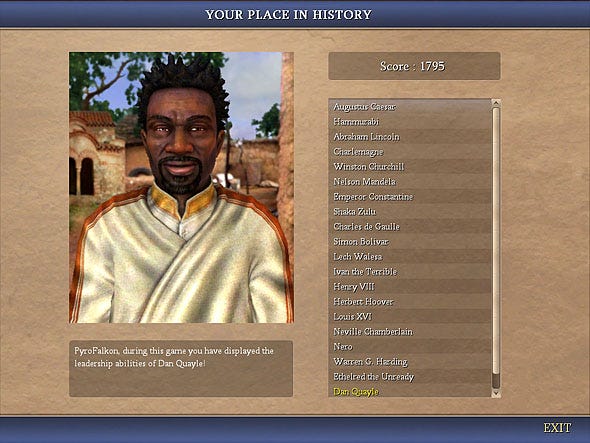

Lately, someone had the idea of making civilizations-specific rankings to score players at the end of a game. Traditionally, when you finish a Civilization game after numerous long hours, you get put on a scale that starts with Roman emperor Augustus Caesar, Babylonian king Hammurabi, and American president Abraham Lincoln, and ends with somewhat less prestigious historical figures such as British prime minister Neville Chamberlain, Roman emperor Nero, and American vice-president Dan Quayle.

This is fun and all, but one of the cool things about the mod, as opposed to “vanilla” Civilization IV, is that it crafts a more unique experience for each civilization in the game. If you play the Tibetans, then you’ll develop a small Buddhist empire in the Himalayan plateau while coexisting with your powerful and dangerous Chinese neighbor. If you play the Americans, then you start in 1776 and have to complete your manifest destiny. If you play the Egyptians, then you start at the dawn of history and probably build the Pyramids and eventually try to avoid being conquered successively by the Persians, Greeks, Romans, and Arabs. In that spirit, wouldn’t it be cool if the end-of-game rankings were also specific to the civilization you’re playing?

Yes, people thought, it would be cool. And also super time-consuming. Including upcoming additions, there are 60 different civilizations in the mod, from obvious ones like Japan and Spain to lesser-known cultures like the Hittites and the Kingdom of Kongo. Each ranked list should have 16 leaders from best to worst, for a total of (excluding two civilizations that are so obscure we don’t know enough leaders to make a list) 928 historical figures.

I took it upon myself to coordinate the project, which means in practice that I made most of the 58 lists and revised those that I didn’t make. Add in many leaders that I looked up but who didn’t make it into the lists, and I probably evaluated more than 1000 historical rulers over the course of the last few months.

(By “evaluating” I mostly mean, of course, skimming Wikipedia articles about the rulers and deciding on their ranking based on a combination of “how long the article is”, “does it have a portrait”, and “does the article include words like ‘greatest’, ‘worst’, ‘tyrant’, and so on”.)

The experience of ranking these leaders was surprisingly transformative. I didn’t dive deep into any specific point in history, but I skimmed about a thousand of those points distributed in time from ~3000 BC (Narmer, the first Egyptian pharaoh) to AD 2022 (Liz Truss, clearly the most ridiculous person to have governed the United Kingdom), and in space from Canada to South India to Easter Island. This gave me a rare and valuable, if imperfect, 2D view of history. Suddenly I could notice patterns. Here are some of them.

I. “Great leaders” almost always means “great conquerors”

This won’t exactly come as a surprise to anyone who has even passing familiarity with either history or grand strategy games, but it was still striking. The most common reason to end up near the top of a list is to have made large conquests and having brought your kingdom to its maximum extent.

Take my list of Assyrian kings1:

Ashurbanipal – last great king of Assyria; the empire reached its apogee and was the largest ever seen in the world thus far; founded the first known library

Tiglath-Pileser III — turned Assyria into a true empire; conquered Babylon

Sargon II — accomplished king, took the name of Sargon of Akkad, founded a new capital, conquered Babylon and stabilized the Levant

Ashur-uballit I — king who turned Assyria into a larger territorial state, marking the beginning of the Middle Assyrian period

Shamshi-Adad I — Amorite conqueror who made old Assyria the center of his Upper Mesopotamian empire

Outside of Ashurbanipal’s library project, all of these are known primarily for conquests and empire-building. Ashurbanipal gets the top spot, despite being remembered as cruel and possibly genocidal, because he made Assyria the largest empire seen at that point in history. How could it be otherwise? We don’t know that much about the moral character of these ancient persons. Even if we did, what criteria should we use, exactly? Across history, it is an uncomfortable truth that success has usually been measured in terms of controlled territory. Power and land are prestigious. And although it offers alternative paths, Civilization, like most strategy games, measures success in that way, too.

There are other ways to be great, of course, some of which we can see in the next part of the list: founding a country, building great cities and wonders of the world like the Hanging Gardens, developing trade, reigning for a long time, inventing the concept of zoos…

Puzur-Ashur I — probable founder of the Assyrian state in the 21st century BC

Sennacherib — moved the palace to Nineveh and made it a great city, maybe built the Hanging Gardens; famous for his role in the Bible; destroyed Babylon; was murdered

Tiglath-Pileser I — great king of late middle Assyria, sometimes identified as the first to have made it an empire; the greatest since Shamshi-Adad

Erishum I — king of Old Assyria who turned the state into a trade hub; ruled for 30 or 40 years

Esarhaddon — neo-Assyrian king who conquered Egypt; short and troublesome reign, but overall highly successful

Queen Shammuramat — only woman to rule Assyria; associated with legendary warrior-queen and heroine Semiramis

Ashur-bel-kala — kept the empire together during the Bronze Age Collapse period, but suffered from rebellions and invasions later in his reign; had one of the earliest known zoological collections

… but the most obviously low-ranked leaders are usually those who were involved with the end of an empire. Sometimes they lost part of it, often all of it. They were the antonym of great conquerors.

Ashur-uballit II — last ruler of Assyria, after the Fall of Nineveh; was never crowned

Ashur-nadin-ahhe I — one of the last kings of Old Assyria, when it became a vassal of Mitanni; murdered by his own brother

Sinsharishkun — king at the catastrophic Fall of Nineveh, shortly before the disintegration of the empire

Sardanapalus — fictional last king of Assyria, described in Greek sources as effeminate, ineffective, decadent, and having died in an orgy of destruction

The last spot in the rankings are often jokes or unusual in some way; here I selected a fictional caricature that the Greeks made up to sound particularly despicable. For other civilizations, the bottom spot is often taken by real but similarly contemptible leaders: incompetent tyrants whose mark on history is laughable, or would-be conquerors who failed and whose reigns and lives ended in humiliation.

The pattern of celebrating great conquerors repeats itself over most civilizations. A few historical leaders are ranked highly for humanitarian or cultural reasons — Gandhi, Abraham Lincoln, Lorenzo de’ Medici — but there’s plenty of Genghis Khans, Alexander the Greats, Julius Caesars, Queen Victorias, Napoleons, and so on. Though it is common, today, to somberly recall the ethical disasters of their conquests and colonial ventures, they still carry an air of greatness, their sins whitewashed away by historical distance, aesthetics, and myth-making.

II. It’s hard to rank “successful” leaders that were also clearly morally wrong

Despite the above, some more recent leaders have not had their sins whitewashed, perhaps because there hasn’t been enough time. I am talking about the dictators of the last century.

The prime example is Adolf Hitler. Clearly not “great”, but also clearly successful on many dimensions, although fortunately he ultimately lost. Where to rank him? I solved his case by deciding he was too controversial to put him on the German list at all. But it wouldn’t do to reserve this treatment to all the other dictators. Mao, Chiang Kai-shek, Stalin, Mussolini, Tojo, Franco, Salazar: they are an important part of history of their respective countries, not to be erased in the name of awkwardness. Besides, the main criterion to end up on a list, whether at the top or the bottom, is fame, and those dictators are certainly famous.

It helps when a dictator is widely seen as ineffectual and ridiculous, like Mussolini. What about ones who scored important victories like Stalin or founded successful new regimes like Mao, while also killing millions of people and causing immense economic suffering?

I don’t have a principled answer to this. I ranked Stalin highly, because as the Russian civilization you’re supposed to role-play the Soviet Union, so being compared to Stalin is a way to say you’ve succeeded. But I don’t feel great about it. I ranked Mao somewhere in the middle — he’s clearly not as “bad” in game terms as a leader like Empress Dowager Cixi, who precipitated the end of the monarchy she led, but there are many Chinese emperors of much fonder memory. Tojo, the prime minister of Japan during World War II, is ranked dead last in his list, because there’s frankly not much to redeem a Class-A war criminal whose country went on to lose the war anyway.

III. Female rulers are rare but there’s almost always a few of them

By my count, the lists include 84 women out of 928 leaders, so about 9%. This is probably a slight overrepresentation: I sometimes went out of my way to represent female leaders, mostly because they’re unusual and therefore interesting. It was probably not necessary to include Boran, a queen who ruled the Persian Empire for less than two years in the 7th century in a time of civil war and decline. But she’s more interesting than some equivalently middling male ruler, in part because there have been only three female monarchs in their own right over more than 2,500 years of Iranian history.

Most of my lists ended up with at least one female ruler. Some of them are highly ranked, like Queen Victoria, Isabella I of Spain, or Catherine the Great. Some ended up near the bottom, like Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi or Joanna the Mad of Castile. Spain is the civilization on which I placed the most women, with 5 out of 16.

It’s interesting how consistent the fraction of female rulers feels. In a long dynasty there’s always, like, one or two episodes of rule by a legitimate female monarch, but not more. There’s also commonly some period in which a woman ruled as a regent for her son, or was influential enough to be considered the true face of power instead of her legitimate husband. We see these patterns in ancient Egypt, in imperial China, in the Byzantine Empire, in 19th-century Brazil, basically everywhere. The most surprising exception was two small sultanates in Southeast Asia, Patani and Aceh, both of which were ruled at some point by no less than four consecutive female sultanas.

IV. We really don’t know much about a lot of history

Here’s another unsurprising observation that nevertheless became salient after doing a lot of amateur research: there’s so much history that basically no one pays any attention to.

In many cases it’s just that the information is not there. One of the 60 civilizations in the modded game is the Indus Valley Civilization, tied with Mesopotamia and Egypt as a cradle of civilization, in what is now Pakistan and India. We know very little about the IVC, because it doesn’t seem to have had writing, and it collapsed before any other civilization could document it. All that’s left is archeological remains. I couldn’t make a list for them: we know the name of exactly zero of their rulers. (Nor do we know, for that matter, the structure of their government.)

Fortunately, other than them and the Toltecs (a civilization in central Mexico that we aren’t even totally sure existed), I managed to find 16 rulers in all cases. In a way, I’m amazed that I did: it’s pretty surprising that we know the king lists of Phoenician and Maya city-states, or ancient countries like Nubia and the early Tamil dynasties in southern India. On the other hand, we often know very little about those rulers. Sometimes it’s an inscription on a sarcophagus, nothing more. As I worked on this project I was reminded that the well-documented reigns of some Egyptian pharaohs like Ramesses II, Greek politicians like Pericles, or Babylonian emperors like Hammurabi are the exception rather than the rule, even within their own culture. The vast majority of antiquity is just gone forever.

And even for those well-documented leaders, it’s not always clear what the quality of the documentation is! We don’t actually know with certainty the dates of Hammurabi’s reign. The great emperor of Persia, Cyrus, considered one of the most important figures of antiquity, is known to the west mostly through Greek writers and the Bible, both of which made him a somewhat legendary figure whose relationship to reality is at most speculative.

Nor is the paucity of information limited to the ancient world. Good luck finding much information about the sultans of the medieval Swahili Kilwa sultanate in East Africa, the pre-imperial kings of Cuzco in Peru, or the Christian kings of Kongo, in what is now Angola, up until the end of their kingdom in the early 20th century. And those are for civilizations that are big enough to have made it into the game. Countless smaller states and peoples get no representation at all.

V. Random fun bits of trivia

On the other hand, history does contain plenty of random stuff to have fun with. Did you know that:

Johan de Witt, the dominant statesman of the Dutch Golden Age, was cannibalized during a riot.

Fjölnir was a legendary ancient Viking king who is famous for having drowned in a big vessel full of mead.

The Maya civilization has 4 of the 25 monarchs with the longest verified reigns in history, including Pacal the Great in fifth place at 58 years. France still has the top spot with Louis XIV (71 years), followed by the UK with Elizabeth II (70 years). There are claims of reigns of more than 90 years elsewhere, like ancient Egypt, Burma, and Korea, but historians don’t really trust those.

One of the predecessors of Mansa Musa of the Mali Empire, possibly Mansa Muhammad, is said to have left to explore the Atlantic Ocean in the 1300s, never to return.

The emperor Huizong of the Song dynasty in China was probably a far better painter than emperor? And also calligrapher. And poet. And musician. I bet he could barely find the time to rule, which is probably why he stopped ruling at some point.

In the ancient kingdom of Axum in what is now Ethiopia, there was supposedly a king named 'Ayzur who was chosen because he was the most handsome man around, and proceeded to reign for a total of 7 hours before being strangled to death by a crowd. (Or something like that, this is barely documented other than in this Wikipedia page)

Irene of Athens was the first woman to ever rule the Roman Empire in her name, which the pope used as a pretext to crown Charlemagne as Emperor of the Romans in the year 800.

Beyond that, though, most leaders in my lists don’t come with that many super interesting tidbits — mostly they all conquered stuff or lost their empire. Oh, and they patronized the arts. There’s a lot of patronizing the arts. And a bunch of peaceful reigns with nothing much happening. There’s a semi-legendary ruler of the Incas whose rule is described as so uneventful that its highlight is “establishing a public market.”

You know how, when you see a same word many times, it starts looking strange and loses all meaning? This is called semantic satiation, and I think I now have something like that with historical figures. I have looked superficially at so many of them, across all times and places, that they have stopped being meaningful in their own right. Now I only see the structures of history: dynasties that rise and fall, succession crises, revolutions, hard times that create good men that create good times that create weak mean that create hard times, conquerors who legitimize their rule by becoming patrons of the arts, the perennial temptation of corruption, the prestige of unifying land into ever larger entities until it they become untenable and collapse. History is not exactly repetitive, but it certainly rhymes, as the apocryphal Mark Twain quote says.

I’m glad I got to feel this, thanks to my big spreadsheet of ranked leaders. Was it the best use of my free time? No, but it was fun, and it’s going to be used in the game, and as a bonus I got a cool blog post out of it.

if you happen to be a specialist in Assyrian history and disagree with any of it, I welcome feedback!

Very cool. This project basically measures status on Wikipedia:

https://pantheon.world/explore/rankings?show=people&years=-3501,2023&occupation=POLITICIAN,RELIGIOUS%20FIGURE,MILITARY%20PERSONNEL,NOBLEMAN,DIPLOMAT,PILOT,JUDGE,PUBLIC%20WORKER

Where is your list of 1000 figures?