These are short pieces of poetic prose I wrote years ago, when I lived and traveled in Europe. I was quite proud of them at the time but never got around to publish them anywhere. Since it is November 1st, it seemed appropriate to translate them to English and put them here.

Gamla Kyrkogården, Uppsala

All Saints’ Day, or as they call it in Sweden, alla helgons dag, is celebrated on November 1st by lighting candles on top of the family grave. As the day draws to a close — which, at such northernly latitudes in November, doesn’t keep you waiting long — the old cemetery of Uppsala turns into a constellation. A fire is lit near the centre, where visitors gather. They greet each other with silent nods.

From what time and place might the tradition of celebrating the dead in the middle of autumn come from? It certainly goes all the way to the early days of pagan Europe, but whether it is Celtic or Germanic in origin, no one truly knows; one mythology has shaped the other, and Christianity did the rest. Halloween in the Anglo-Saxon countries, the Día de Muertos in Mexico, and alla helgons dag in Scandinavia are the diverse, sometimes contradictory manifestations of a same ancestral idea.

Long before its evangelization, Uppsala was a place of worship of considerable importance for the ancient Swedish peoples. In the 11th century, the German chronicler Adam of Bremen described its temple as the most illustrious of Norse paganism: gold was ubiquitous, and on a triple throne sat the august statues of Thor, Odin, and Freyr. To Thor a sacrifice was made in case of famine; to Odin, in times of war; to Freyr, on the occasion of a wedding. Of this Old Uppsala there remains nothing, today, but a row of burial mounds for forgotten chieftains, to the north of the city, standing there like swellings of the belly of the earth.

Christianity, with its known tendency to assimilate the religions it aspires to displace, did not hesitate to build a church where there was a temple. Later still, on the hill at the centre of modern Uppsala, it erected a great cathedral, the mightiest in all of Scandinavia. It seemed natural that an archdiocese would establish itself in a place where paganism had flourished. The cathedral gave rise to the cemetery; it also led to the foundation of the university. In an indirect way, it is to Thor, Odin, and Freyr that I must credit my presence here as a student — and my visit to this old graveyard.

Of course, the worship of the Æsir, the Vanir, and the Dísir has long vanished from Sweden. No runic stones are to be found among the graves of Uppsala; no Viking boats are motionlessly carrying the dead towards Valhalla. Instead the vast majority of the tombs are either Christian or secular. Not all of them, however.

Like the rest of the Western world, Sweden in the 21st century is a land of immigration. Walking among the rows, I see here and there a recent grave, belonging to the Muslim faith. Then I arrive in front of an intriguing one: it is adorned with a strange symbol, half-man, half-bird, with a full beard and outspread wings. A kind of angel, perhaps. It is the Faravahar, a sacred emblem of Zoroastrianism.

Who still remembers anything about Zoroastrianism? It was one of the first monotheistic religions, and the state worship of the Persian Empire; it was practiced everywhere from Anatolia to India. Today only a few tens of thousands of followers remain. Just like the ancient pagan faiths of Europe in the face of Christianity, the teachings of Zarathustra were driven out of Iran by Islam. In a handful of places the Zoroastrians still tend to their holy fires, the oldest of which has been burning without interruption for a thousand and half years; but someday, inevitably, the fires as well as the religion itself will find themselves on the threshold of extinction.

In Uppsala, the night of All Saints’ Day, a candle illuminates the carved Faravahar just like others light up the Christian crosses. On the tombstone, someone put a picture of the deceased next to his name and the dates of his birth and death. He had been twenty-three years old.

A gust of wind makes the tiny flame flicker, but it doesn’t go out.

Vyšehradský hřbitov, Prague

To visit the most important cemetery of the Czech Republic, you have to climb all the way to the old fortress of Vyšehrad. This place falls under the radar of most tourists, who prefer to crowd into Prague Castle, Charles Bridge and the squares of the old city. We have ten days in Prague. It’s just after Christmas. We have time.

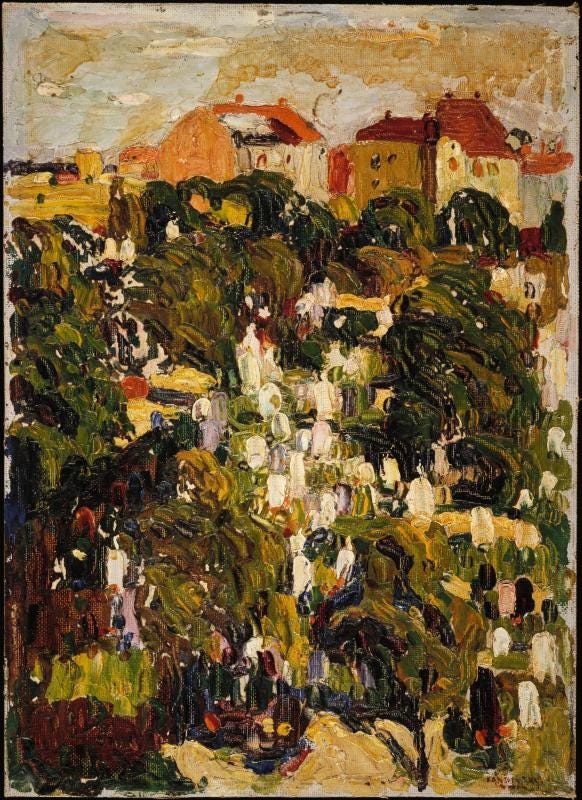

Vyšehrad is a vast thing of brick and snow that dominates Prague from the south, and in the centre of which rises the double steeple of the Basilica of St. Peter and St. Paul. From atop the fort’s walls, we are rewarded with a superb view of the city and of the Vltava river. The snow scrunches under our aimless steps, and we eventually wander into the graveyard. The tombstones are densely packed. Here are gathered some of the most celebrated Czech figures, from writers (Neruda, Čapek) to painters (Mucha) to classical composers (Smetana, Dvořák).

I linger in front of the grave of Bedřich Smetana, noticing a golden engraving on the black granite: a music staff on which a few notes seem to be dancing alongside a treble clef. Smetana was the creator of some of the most beautiful pieces of Czech patriotic music. During my (quickly abandoned) formal studies in music, many years ago, we had analyzed his best-known work, Vltava, or as the Germans call it, Die Moldau — a symphonic poem that tells of the river, its birth from the intermingling of mountain springs, the hunting and wedding scenes to which it provides a backdrop, the rapids where it turns into a violent rush, and finally the centre of Prague, through which it flows with imperial triumph.

But Smetana composed much more than Vltava. The second-most famous of his symphonic poems takes, as its subject, the stronghold where we currently stand: Vyšehrad recounts the tale of the old castle, its grandeur, its majesty, and its ultimate ruin. Among the rows of tombstones of this fallen fortress, the arpeggios of Smetana’s music are almost audible, like a faint echo. One hears the resounding past glory of this small country that was called Bohemia and now bears the name of Czechia.

Not too far from there, we spot the grandiose monument to Antonín Dvořák. Unlike Smetana, Dvořák’s likeness has been immortalized into a bust, sheltered under an arch with painted red and white domes. They say that Smetana understood more than anyone the true essence of Czech music, but beyond the borders of his country, the world only has eyes for Dvořák. Who has a full-size statue well positioned in front of the Prague opera? Dvořák. Who composed the immensely renowned Symphony of the New World and the immortal Slavonic Dances? Dvořák. Who is the author of that delightful Piano Quintet in A major that I sometimes listen to on repeat, when the sun is down and the profound blue of dusk fills the sky and the depths of my soul? Dvořák, of course.

I’ll admit it: of these two composers that I (wrongly) picture as rivals, I, just like everyone else, prefer Dvořák too.

We exit the cemetery and enter the Basilica of St. Peter and St. Paul. By a happy coincidence, a small concert is being presented. We mingle with the sparse crowd. Four or five musicians are playing some piece of chamber music that I don’t recognize. I’m pretty sure it is neither from Smetana, nor from Dvořák.

Waldfriedhof, Munich

Wald is German for forest; Friedhof means cemetery. The Munich Waldfriedhof is a hybrid, an in-between, a place of life and a place of death. Vast and solemn, and at the same time intimate and familiar. Visitors are rare; when they pass each other, they nod briefly, but keep their distances.

It is early January. A thin fog haloes the edges of the tombstones and the bark of the trees. Everything is a shade of green or grey. The noises from the city are softened by the damp vegetation. Soon enough, I realize I’m lost.

One does not wander through the Waldfriedhof as in any forest, or as in any graveyard. Here, more than anywhere else, living matter and dead matter have found how to coexist. A set of small wooden monuments, each and everyone of them showing a crucified Jesus or a maternal Virgin Mary, looks as if it had just sprouted from soil, like a patch of mushrooms in autumn. On top of luxurious tombstones, a luxuriant moss grows. At times, it seems that the graves dominate the landscape; moments later, the trees have clearly gained the upper hand. But what is happening has less to do with competition than with symbiosis. The trees feed on soil, which is made of the bodies underground that have decomposed down to mere bones and a name carved into stone. In return, the dead benefit from the most complete rest one could conceive of. Here reigns peace, which in German is Frieden.

The Austrian architect Friedensreich Hundertwasser was what we could call an eccentric. He loathed the straight line; he built undulating floors to imitate the irregularity of nature. He added colours where there had been nothing but the industrial grey of a waste incinerator. At the time of his death, he asked to be buried in a forest of New Zealand, naked, without a coffin, with a small tulip tree planted just above him. Today the tree has grown. It thrives.

Hundertwasser, despite (or thanks to) his eccentricity, touched upon something very fundamental. Who doesn’t have a loved one who expressed the wish that their ashes be dispersed in the immensity of the sea or sky? Better yet: one can now buy biodegradable funerary urns, containing the seed of an ash tree, a pine, or a Ginkgo biloba. Plant your beloved departed and watch them, over time, reincarnate into the maple tree at the bottom of the backyard. Nowadays the call of nature is being heard from beyond the grave.

The fog is lifting. A pale sun dapples the branches. A bird, coming from nowhere, lands on a wooden cross, and then immediately flies away to another nowhere. An old woman, standing still, gazes at the tombstone of someone she used to know. The tree nearby has grown taller than the rest and is almost touching the sky.

In the Munich Waldfriedhof, we are reminded that each tree is a funerary stela; that each monument is but a piece of rock pulled from the crust of the planet; and that each human body will one day become compost. At the time of my death, it is in a place like this that I want to end up.

I really enjoyed discovering Dvořák’s work by reading your magnificent texts. May I suggest that you include a musical prescription at the end of your blog posts in the future? I have confidence in your ability to find musical pieces that go well with your text. I think your knowledge of music is way above average and you could broaden the horizons of people who, like me, know nothing about music.

A beautiful, contemplative piece