I don’t visit Toronto often, but I was there for less than 48 hours last weekend on an impromptu, family-reasons-related trip. It was maybe my fourth time there. It so happened that I had nothing important to do for an entire day, so I just spent it walking around the city.

It was a beautiful summer Saturday. People were out and about. They sat in parks, had picnics, filled the coffee shops and restaurants, or prepared for an Indian food festival in front of City Hall. Some were enjoying the sun on the beaches that border Lake Ontario, next to the quaint neighborhood where the pianist Glenn Gould once grew up. You can see the spire of the CN Tower from there, in the distance.

We were staying in North York, at the end of the subway line. North York looks as if a little piece of East Asia had drifted and settled here in North America. Yonge Street in that area has dozens of tiny restaurants, little more than stalls, serving dishes of the Chinese, Korean, Japanese, or Vietnamese cuisines. I had the best tea-flavored ice cream I’d ever had, as well as some great Sichuanese food. Everyone around me was of Asian descent.

I heard at least a dozen languages. Only 55% of Torontonians speak English as their mother tongue. 47% were born outside of the country. This place is where the huge numbers of people who move to Canada choose to settle, about 100,000 per year, apparently. Of the world’s large cities, it is one of the most diverse, and possibly the one with the largest proportion of foreign-born immigrants.1

As I walked among these seemingly happy and extremely diverse people, a thought occurred to me: is this, perhaps, the closest we can get to utopia?

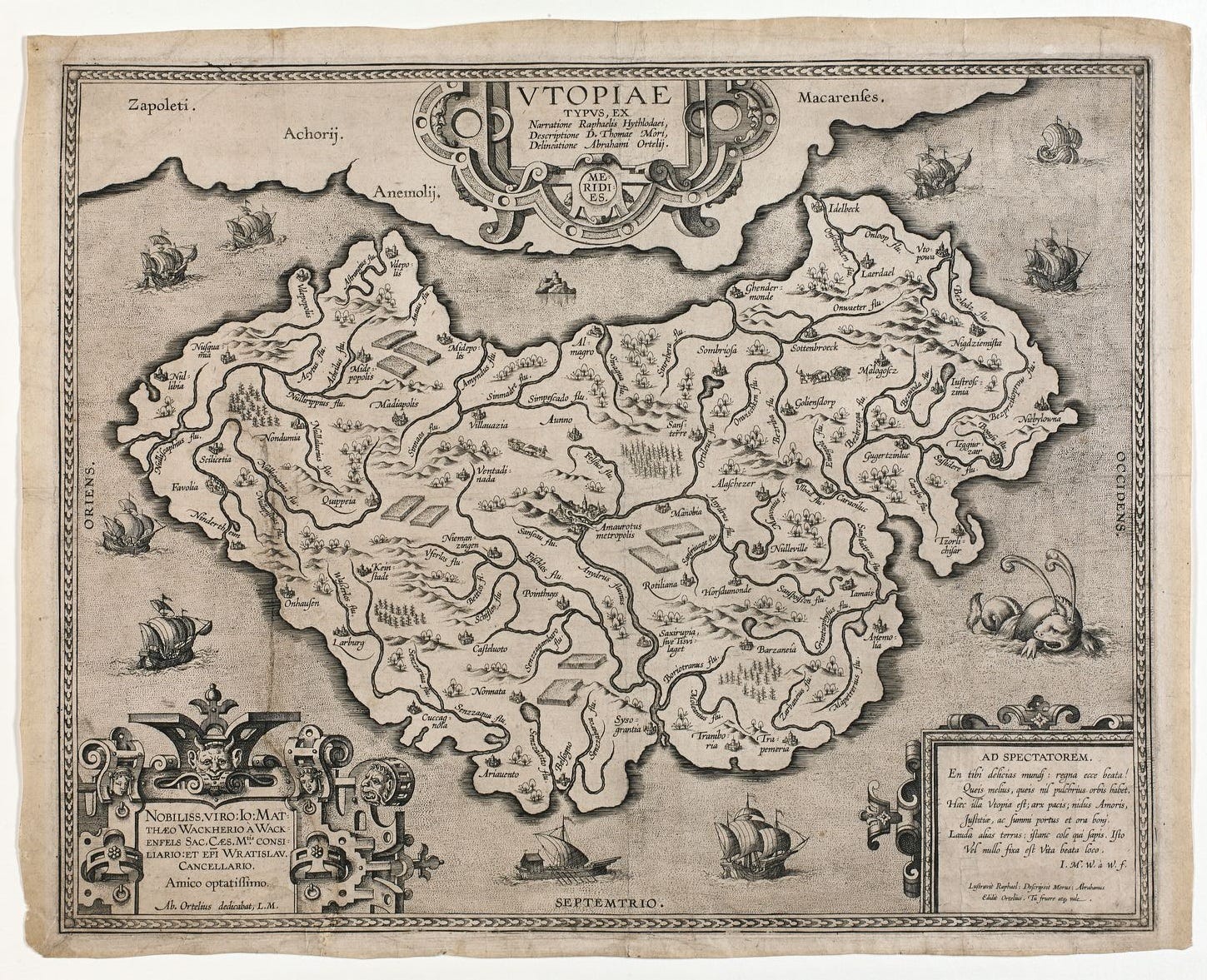

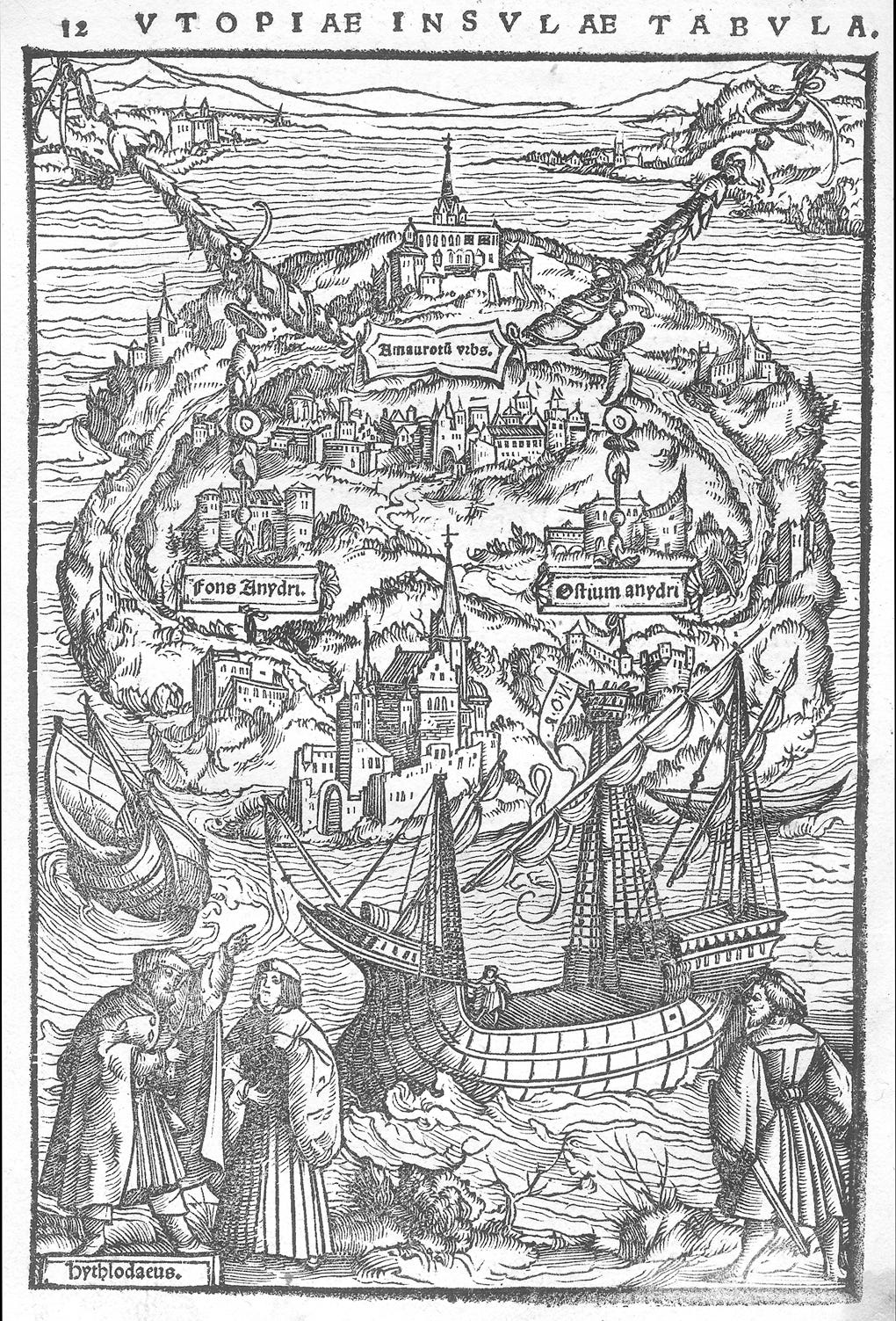

A utopia is supposed to be a perfect society. The word comes from Thomas More’s 1516 book of the same name, and it means no-place. More’s fictional Utopia is an island somewhere in the New World. It has a closely controlled population size, an elected prince, a welfare state with free hospitals, and access to euthanasia.2 It forbids private property, though it does have slaves, two per household, consisting mainly of prisoners. Meals are taken communally; there is little privacy, so that, in a way that echoes the later panopticon idea, citizens always remain on their best behavior. The Utopians practice several religions and are explicitly tolerant of each other; they even allow (though discourage) atheism. They avoid war when they can, and when they cannot, they try to take prisoners rather than kill their enemies.

Thomas More’s Utopia doesn’t exactly sound perfect (slaves? no property?), but it has some interesting elements, especially for 16th-century Europe. It inspired countless other attempts to design perfect societies, sometimes even implemented in real life. But typically, all these utopias, fictional or not, feel somewhat uncomfortable. The society in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World is supposed to be perfectly designed, but it feels disgusting enough that we call it a dystopia instead.

The reason might be that, having found the “perfect” rules for society to run well, utopias need to enforce those rules and disallow any deviation from them — since those deviations would be less perfect. The result is that utopias are, or at least feel, totalitarian. Stifling. Anti-human.

A true utopia, instead — and here I am paraphrasing a friend’s words — would necessarily be full of problems. Problems are, well, problematic, but they can be solved. This allows people to improve things, to grow. A totalitarian society that tried to solve all problems from the get-go would be static, depressing. Not to mention that it would certainly fail to predict all future problems, and without a capacity for self-correction, it would set itself up for catastrophic failure, the same kind of failure that befalls all totalitarian regimes in the long run.3

If perfectly well-designed utopias are actually dystopias, then true utopia might end up looking a lot like… a modern liberal democracy. One in which people are as free as possible to pursue whatever they like, and solve problems if they want to. Or not, if they don’t want to. One in which people of diverse ethnicities and religions live together in harmony. One in which we argue endlessly about what our government should look like, but where the arguing itself is considered important, if sometimes unpleasant.

Any liberal city or country could qualify, but I didn’t muse on utopia as I wandered around San Francisco or Paris or Austin or New York City. Why Toronto?

Where I live, in Quebec generally and in Montreal specifically, people consider Ontario generally and Toronto specifically to have somewhat of a poor reputation. They’re boring. Wealthy and big, sure, but nothing really exciting happens there. There’s no culture. You don’t go to Toronto to party, or have fun, or attend festivals; Montreal is a much better place for any of that.

In absolute terms this reputation is undeserved, at least today. There’s obviously a lot of culture in Toronto. Word on the street is that the city has begun to shed its reputation as a sleepy place, probably propelled by its massive immigration-fuelled growth. Torontonians have plenty of restaurants and art galleries and concerts and so on. Good for them!

But at the same time — what exactly is Toronto’s identity? It’s hard to come up with any clear answers other than Canadian multiculturalism. Toronto is a city with no individual identity, because its purpose is to accept everyone’s identities and allow them to mix however they want to.

Most utopias, being imaginary and ideal, have little going on in the realm of culture. We don’t really care about what kind of cuisine they eat, what their literature says, what language they speak and what architecture they build. Utopias are experiments in solving the mechanics of society, not in creating realistic and lively cultural identities. Besides, dynamic culture might well be incompatible with totalitarian enforcement of perfect laws.

So any place with a strong, identifiable culture will not feel like a utopia. That excludes most European cities, and Montreal, and also the major cities of the United States, which are the engines of Anglophone and global culture today. It excludes most of the world, really. Toronto, and to a lesser extent the rest of English-speaking Canada, could in fact be seen as an extremely unusual place — a perfect combination of being just outside the cultural behemoth of the US, and speaking the same language, which means that a lot of its cultural talent is drained there; and having adopted an ideology of multiculturalism that explicitly seeks to allow multiple cultures to live together without needing to share much more than the English language and adherence to local laws. The result is something unique, and even unique in its way to be unique.

Like any utopia, it is an experiment. To certain people, especially a certain kind of extremely online right-wing Americans, it is an experiment that is going badly — they write that Canada is sliding into authoritarianism (it isn’t) or that it is seeking to kill its own citizens with euthanasia (a nonsensical opinion, though there are valid issues to be raised). Most critiques of the sort are exaggerated, but it is true that the country and Toronto in particular have problems, most notably in housing. But that’s what a utopia is — a place where people are free to solve problems.

I come back from Toronto thinking that I don’t love it. I can’t say I’ve ever been attracted to it, when I’ve been attracted to New York and San Francisco and Paris and maybe even Austin. Maybe utopia isn’t for me.

But I also don’t hate it. In many ways, it is really nice, and I hope that the experiment turns out well.

The only contender is Miami. But the immigrants there are for the most part Cuban or otherwise Latin American, making it less diverse than Toronto.

One could draw a parallel with Canadian laws around medical assistance in dying, which have been the subject of much criticism and annoying Twitter conversations.

More’s Utopia, incidentally, does include something like a self-correction mechanism for religion and government:

In these [prayers] they acknowledge God to be the author and governor of the world, and the fountain of all the good they receive, and therefore offer up to him their thanksgiving; and, in particular, bless him for His goodness in ordering it so, that they are born under the happiest government in the world, and are of a religion which they hope is the truest of all others; but, if they are mistaken, and if there is either a better government, or a religion more acceptable to God, they implore His goodness to let them know it, vowing that they resolve to follow him whithersoever he leads them; but if their government is the best, and their religion the truest, then they pray that He may fortify them in it, and bring all the world both to the same rules of life, and to the same opinions concerning Himself, unless, according to the unsearchableness of His mind, He is pleased with a variety of religions.

I had this exact same feeling staying in Vancouver this summer! And I interviewed someone earlier in the year who thought Montreal was a utopian city! (I’m now planning a trip!)

Maybe Canadian cities are just utopian because they are so multicultural, and because they seem designed to be a good place to live (so much culture, so much greenery, so many bike paths and places to stroll!)

I definitely agree that Utopianism relies on two things: systems designed to be of the best benefit to the most people, but also the freedom for those people to live the way they want to within their local communities. So far, democratic socialism seems to provide some kind of happy medium there, but it will certainly never be perfect!

Utopia is an evolution not a destination! And many of our societies are much more utopian than More could have imagined!

as a torontonian I endorse this post