Two New Ways for the French to Be Smug About Food

Bringing cultural ancestry and demography into the French vs. American cuisine debate 🍟

I’m not sure there’s a topic that people online like arguing about more than “which country has the best cuisine?”. It’s like an undercurrent to all of culture, ever present, ever ready to erupt on the public stage. It somehow always involves French food, which is often pitted against Italian, Chinese, or American food, among many others.

Sometimes we get particularly intense eruptions, like two weeks ago when Philippe Lemoine went viral with this tweet:

which led to an extraordinary wealth of responses, including Nate Silver, and Zvi Mowshowitz, and also this extraordinary headline from New Zealand:

Pretty much every single opinion on the topic has been expressed, including classics such as “it depends on how you define the question”, “there’s more food diversity in the US”, “there’s a healthier food culture in France”, and “they’re both bad, Mexican/Italian/Chinese food is where it’s at”, so in theory there should be little that I can add. Yet there are two points that are almost never discussed, which is odd considering how important they seem in a conversation about ethnic cuisines. The first point is shared ancestry. The second is demographics.

I. The American and French Cuisines Are the Same Cuisine

What exactly is French food?

I can come up with a number of French culinary specialties, like the baguette, the macaron, escargot, onion soup, cheeses and wines, and so on. Yet none of that quite seems to capture the essence of French food the way I can summarize, say, Japanese food with “ramen, rice, raw fish, miso soup.” And while there are plenty of cuisines that I also can’t intuitively summarize (“What exactly is Uruguayan food?”), the French culinary tradition is unique in that it’s simultaneously widely recognized as one of the most influential in the world.

That apparent contradiction, however, easily resolves itself: French food is difficult to wrap one’s head around precisely because it is so influential.

With roots in the ancient and medieval world, the core of French cuisine is essentially the same as the rest of Europe: bread, roasted and boiled meat, pies, various dairy products and vegetables. But then it went on to develop a refined cuisine of its own, distinct from its neighbors in Germany, England, Spain, or Italy.

For reasons that probably have to do with the immense power and population (see below!) of France during the early modern period, the refinements of French cuisine went far beyond those of the surrounding countries, with the single exception of Italy. The country accumulated a lot of culinary prestige, which it still carries into the 21st century. This means that any highly refined Western dish (again, except for Italian) tends to be called French by default, or at least is highly French-influenced.

But the influence isn’t just in haute cuisine. A lot of basic features of Western cooking are essentially French — if not invented in France, then popularized there. This includes:

Salt and pepper as the default seasoning

Basic sauces such as mustard, mayonnaise, vinaigrette, and gravy

French fries (Belgium and Spain have a claim to have invented them, but it does seem that they’re actually as French as their name suggests)

Steak tartare, the forerunner to the hamburger steak (though one could equally say it’s German)

Sliced raw vegetables served as crudités

So if you’re sitting in a restaurant in the United States, eating a hamburger that has some mustard and mayonnaise, accompanied with fries, and there are salt and pepper shakers on the table, then you’re essentially eating French cuisine. In this scenario, only the concept of a hamburger sandwich is decidedly non-French (it’s either German or genuinely American).

Humans and chimpanzees, though obviously very different animals, share 99% of their DNA. Similarly, American food and French food share 99% of their cultural baggage. Or maybe 95%, it doesn’t matter, this is just a metaphor.

American cuisine and French cuisine are essentially the same cuisine: Western. Which happens to be French to a large extent.1

Of course, the remaining 1% or 5% is still pretty important, both for chimpanzees/humans and for French/American cuisine. That 5% contains the baguettes and macarons and escargots one one side, and hamburgers and Philly cheesesteak and Texas BBQ on the other. In other words, it contains the recent innovations that haven’t been adopted elsewhere, and the quirky specialities that depend on local ingredients or cultural practices. For example, whether there’s a taboo on eating horse meat, or snails, or raw meat.

It can be fun arguing about the 5%. It may even be meaningful to say that either the American or French 5% is better than the other. But remember, when you do so, that you’re arguing over a tiny sliver of culinary culture that floats at the surface of a much bigger common pool.

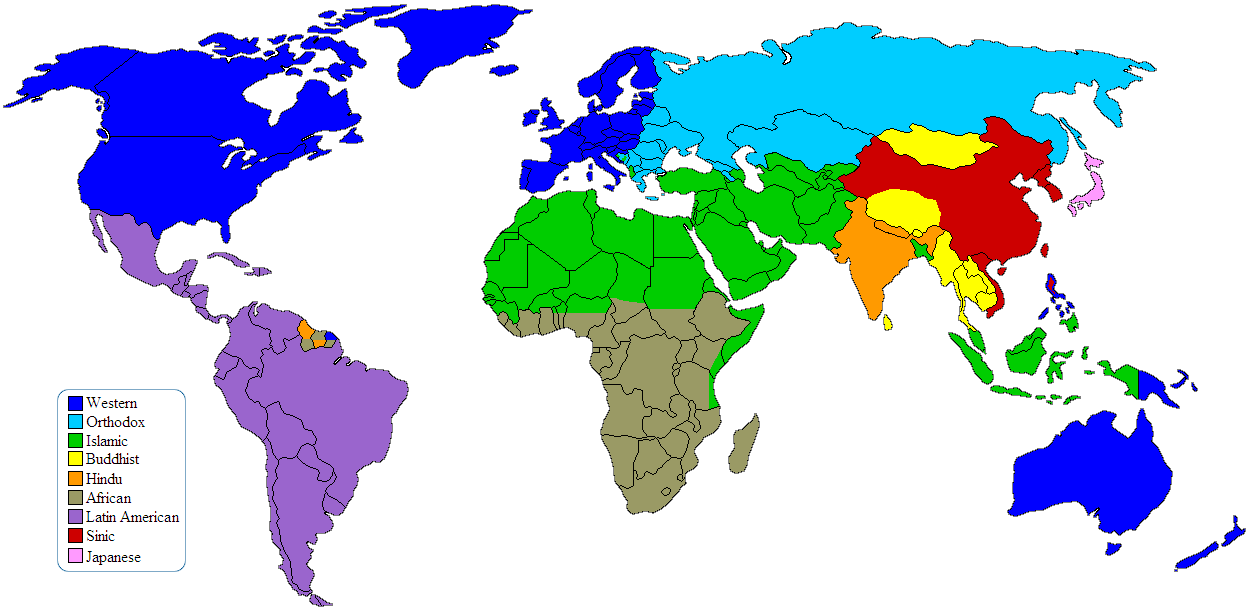

(As for comparisons with other cultures, the percentage can vary. Traditional Western food is very different from traditional Chinese or pre-Columbian Mexican food, both of which evolved separately — though there surely are commonalities coming all the way from prehistory. Meanwhile, Middle Eastern and Indian food share a bit more with the West. Ultimately this comes down to difficulties in defining what “the West” is.)

II. Demography Is Destiny

Whether for serious economic variables or silly debates over food, we tend to overuse “sovereign states” as a unit of analysis. The result is that it’s common to compare the cuisines of regions of the world that differ massively in terms of population, just because countries are easier to think about than subregions or macroregions. France (pop: 68 million) and Italy (pop: 58 million) thus often get pitted against giants such as China (1425 million), India (also 1425 million), and the US (340 million).

But it seems pretty clear that, other things being equal, having a larger population will tend to generate a more flourishing culinary culture. More people to invent dishes and to consume them. More wealth, which leads to more demand for haute cuisine, more imports of luxury foods like spices and exotic fruit, etc. More diversity, often, due to incorporating subregions with their own cultures, or accepting immigration, all of which allow remixes and fusion cuisine and the invention of new local delicious dishes.

So one would naïvely expect large countries to win cuisine contests by default. And indeed they’re often up there. Well, except for Indonesia (pop: 274 million), whose food nobody ever talks about.

To make things fairer, it’d be interesting to divide by population and determine the “best food per capita,” whatever that might mean. Countries like Indonesia and Brazil, with a large population and no strong food reputation, would sadly end up at the bottom of the list. The winner would probably end up being some tiny country with a strong culinary tradition, like Lebanon or Greece. I imagine that France and Italy would easily rank above China, India, and the US.

The true unit of analysis, though, isn’t sovereign countries: it’s “cultures,” which of course can be defined in all sorts of ways. You could do subnational cuisines: Sicilian, Provençal, Sichuanese, Texan, Tamil, Quebecois, etc. You could do supranational cuisines, too: Arab, Mediterranean, Western, South Asian, Andean, etc.

Here again we can use population as a guide: pick regions, whether subnational or supranational, with similar populations, and compare those. For instance, to pit France against opponents of its caliber, we could do:

France (68 million)

Italy (58 million)

Sichuan (81 million)

Northeastern US (58 million, counting Pennsylvania and everything northeast of it)

Korea (77 million, both North and South)

Tamil Nadu (72 million)

Which of these has the best food?

We could also want to compare large macroregions:

East Asia (1.6 billion)

South Asia (1.9 billion)

The Western World (the Americas + Europe + Oceania, 1.8 billion)

Again, which of those has the best food, when French and Italian and American ally against Japanese and Korean and Sichuanese and against North and South Indian and Pakistani and Afghan?

Of course, there is much more to the story than current demographics. To truly get a fair basis for comparison, we’d have to compare historical populations, too. France used to be one of the largest countries in the world, and the largest in Europe by far, which is a partial explanation for how it got so good at food.

We’d also want to add in a bunch of other variables, like economic strength, artistic and technological achievements, geographic extent, and military power, all of which can be summed into an aggregate measure that we might call influence. It is probably true that the countries with the best cuisines are those whose influence, summed across history, is the greatest.

The US, as of today, clearly wins on most of these variables. Its only weakness is its young age: it hasn’t had time to build culinary prestige that is clearly independent from France and the rest of the West. But it’s getting there, notably thanks to its melting pot of various immigrant cuisines. Give it a couple more centuries, and the American culinary tradition may well surpass the French and Italian and Chinese ones in popular global culture.

For now, though, if I were forced to make a choice, I would have to hand it to the French over the Americans. Sorry, Americans. You should innovate more — you’re pretty good at that!

I have too many parenthetical statements about Italy so here’s a footnote. Italian cuisine is interesting because Italy is clearly at the core of what it means to be Western — being the center of the Western Roman Empire and Western Christianity and the Renaissance and so on — and yet its cuisine is highly differentiated from the rest of Western cuisine. I’m not sure why its kept its identity separate from the West to a larger extent than France was. Maybe because it consisted of a bunch of small states for most of its history, unlike France?

> "I’m not sure why [Italy] kept its identity separate from the West to a larger extent than France was. Maybe because it consisted of a bunch of small states for most of its history, unlike France?" - It might also have to do with geography and climate. Italian food is highly dependent on the availability of Mediterranean produce (same as Greek food): olives, herbs etc. These could not easily be found when Roman culture expanded further north, so the converted Germanic tribes had to make do with whatever was available in their lands. French cuisine, being a much later development, could use the colonial infrastructure of modern times to access a wide variety of resources that were also available to the other colonial powers of the time. Another problem is that both Italian and Greek cuisine are actually not their original selves. Both today make heavy (almost defining) use of tomatoes, which are a South American import of newer times. Additionally, much of Greek cuisine is actually Turkish or Arabic, often even preserving the original names: Halva, loukoumi, imam, tzaziki and so on. These are not words in Plato’s tongue. So these are recent developments (Turkish occupation of Greece goes from 15th to 19th cent.) and the original cuisine of Greece (and much of pre-pizza, pre-tomato Italian cuisine) is today lost. Spaghetti too is rumoured to be a Marco Polo import from China, so what was pre-medieval Italian food? Probably just bread, onions and fish. Poor people's survival food, like in much of ancient and medieval Europe.

A good way to look at why Italy (and Iberia and Greece) are different is to look at the primary fat. In well watered NW Europe, one can water dairy cattle and you rely on butter. On the drier Mediterranean rim you end up with olive oil based cooking. You get some exceptions - like the Po valley in Italy where it is much more the well watered rolling planes like the Ile de France. There you see all sorts of crème and butter based Italian dishes. Otoh inFrance you get Provençal style cooking that is much more olive oil focused and does not use butter like it is an unlimited ingredient.