Innovation — in science, technology, economics, and society — is what will save us. All of the problems you can think of will be solved with ingenuity, provided that we don’t accidentally destroy ourselves. The only alternative is stagnation and pain.

We know this because innovation has done so many times in the past. In the 1970s, there was widespread concern with overpopulation: soon, it was thought, there would be too many humans, and we wouldn’t be able to feed them all. The 1973 dystopian movie Soylent Green epitomized this. At the same time, however, the Green Revolution in agriculture was underway. Major improvements in food production allowed our civilization to keep growing while famine has become rare.

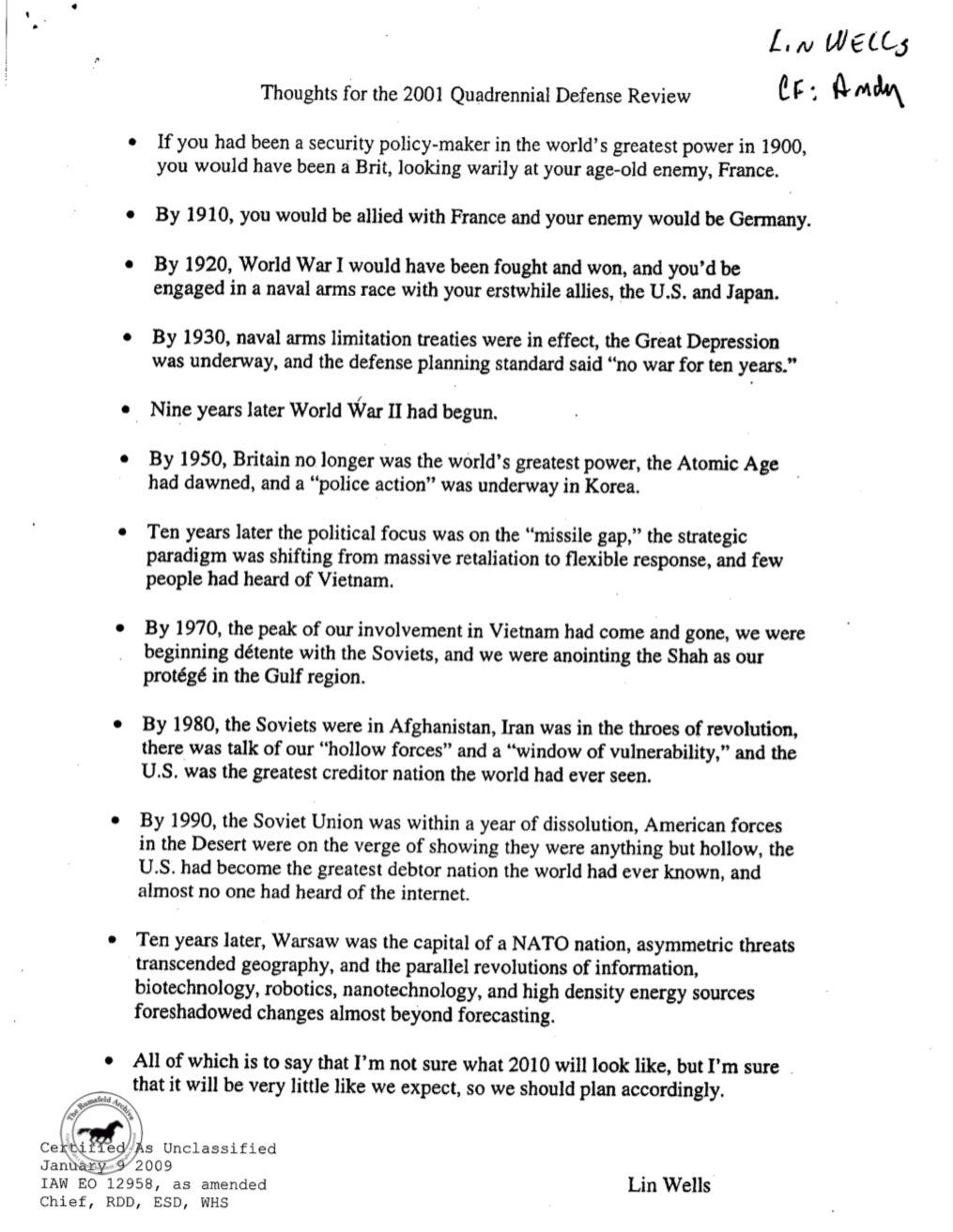

But in another sense, we don’t know. We have no idea what the eventual solutions to our problems will look like. If we did, that would amount to having solutions already, and the problems wouldn’t be real problems — it wouldn’t be innovation.1 Indeed, in many ways, progress is literally unpredictable. We can make educated guesses about future technologies and developments, but many of those guesses will be wrong in both nature and timing.

Given these two opposite forces, how reasonable is it to expect the unexpected?

To make it a concrete question: how reasonable is it that we’ll manage to solve (say) climate change, with technology — and thereby avoid the negative consequences both of doing nothing, and of doing things that would dramatically decrease the living standards of billions of people?

Some people think the answer is “very much not reasonable.” They liken belief in innovation to belief in magic, or in religious miracles. Sure, they’ll agree, if some technological miracle happened and did away with climate change, it would be nice. But we can’t count on such miracles. We have to do something now, with the solutions that currently exist.

On the other end of the spectrum, some people think the answer is “quite reasonable.” I count myself among them. I think that we’ll figure out a way to solve climate change (and many other hard problems) even though nobody, right now, can totally foresee it.2

To the people in the first group, this makes no sense: how can you count on something you can’t see coming? That sounds, as Jason Crawford put it, “fanciful and naive.” Whereas pessimism seems sober and wise.

Pessimism seems prudent, because miracles are unreliable. They are divine interventions; the result of forces that we can’t comprehend. They are something that happens to us rather than something that we do.

I think that the word “miracle” to describe innovation is extremely ill-chosen. Why, then, do technological pessimists use it? My guess is that it’s because they lack imagination. Not only can they not imagine the specifics of the solutions to our problems (which nobody can reliably do); they also cannot imagine that these solutions even exist. Perhaps more strikingly, they also certainly can’t imagine finding those solutions themselves — which, to be fair, is probably almost always right, since they’re pessimists. They have not studied the history of progress, they don’t know much about how technology works, including social and political technology. And so, to them, solving problems feels alien. It’s a force they can’t comprehend. Miracles.

As a result, they see solutions as just “happening.” They don’t have any sort of clear idea of what the people who invented writing, the bicycle, the telegraph, or penicillin, were doing — how they used their creativity to come up with solutions. Even when we have a good historical record, they don’t even know who the inventors were. To them, these inventions just happened.

But of course, innovation does not just happen. It is not made of god-given miracles,3 or strokes of pure luck (though luck plays a role). It is made of the work and creativity of people trying to solve problems.

Viewing innovations as “miracles” deprives humanity of agency. It is a failure of empathy with all inventors that have preceded us. And it has terrible consequences when it spreads through a population, for it is self-fulfilling: if we end up believing that innovation is always just a stroke of luck, then we may fully stop seeking it, like almost all societies before the Enlightenment. In such static societies, innovation is random and, indeed, almost miraculous.

But we’re not a static society, and I hope we never go back. And so we need to stop thinking that miracles will happen, just like we need to stop thinking that they won’t. We should reject the concept entirely. We can do better than miracles.

I’m hand waiving a lot of stuff here, obviously. Sometimes the solution is known but is hard to execute. But, alternatively, we can view this as requiring innovation in the realm of execution.

This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t do anything in the face of climate change or any other recognized problem. On the contrary! Innovation is all about finding solutions, and these solutions need not be technological. However, technological solutions very often have the benefit of improving welfare and leading to more innovation, which is better than “solutions” that involve reducing welfare and that lead to stagnation.

Arguing against the use of the word “miracle” gives a neat second meaning to Roger’s Bacon great post:

Einstein didn’t publish his four papers thanks to the visitation of an angel. Fuck miracle years, indeed.

There's an ethical dimension to this discussion as well: we have a responsibility to address the problems that we see in the world; to wait for miracles is to avoid that responsibility.

I feel the problem is which kind of innovation are we expecting there? I tend to agree with the idea that no technology could save us. Not that it's not possible to be saved by a technology, but because it would only postpone and probably deepen the problem.

The kind of innovation we need right now is a deep modification of the way we interact, both individually and collectively, with our environment.

There's a great french fantasy book titled "Winning the war", it's always struck me as our main problem : we've been winning the war for quite a long time now. And yet we still act as if we were under fire. But finding new weapon won't help.