Aesthetics as Epistemic Humility

AWM #92: Further thoughts on why effective altruists should care about beauty 🪼

A few months ago, I wrote an essay called Guided by the Beauty of One’s Philosophies, which examined the importance of aesthetics to organizations and movements. I used Effective Altruism as a case study: I argued that EA could do more good by having more intentional aesthetics. The essay generated a fair amount of reaction — I enjoyed this response post, for example.

Meanwhile, some people within Effective Altruism decided to launch a (very on-brand) criticism contest to encourage the best critiques of the movement. I considered submitting my essay, since it was published within the contest’s acceptance period. However, I hadn’t meant it to be a formal critique of Effective Altruism. It seemed pertinent, then, to write another piece that would formalize my thoughts around aesthetics and EA.

This is that piece. I am going to submit both, considered together, for the criticism contest. I will formally submit to the EA Forum a few days after having published this on my blog, so please feel free to comment and give feedback.

Compared to the original essay, this one spends more time examining the fundamentals of what beauty is and why it’s important. Then, having established that, I state my main criticism of EA and offer concrete suggestions. The piece is organized as questions-and-answers in five sections:

What beauty and aesthetics actually are

The benefits and caveats of caring about aesthetics

The aesthetic critique of EA

Concrete suggestions

Concluding remarks

1) First, we need some definitions. What exactly is beauty?

Beauty is a complex concept. The main difficulty in defining beauty is that it is incredibly general. All of the following are routinely described as beautiful (or ugly): people, food, houses, clothes, illustrations, abstract shapes, landscapes, astronomical phenomena, animals, plants, stories, sounds, mathematical concepts, personalities, theories, color combinations, body parts, machines, behaviors, scenes. A good concept of beauty must apply to everything in this list and more.

My current best encapsulation is that beauty is a mechanism to pay attention to whatever is good. “Whatever is good” is still incredibly general, but that’s a feature, not a bug: it simply refers to everything that a person wants or needs, consciously or not, at any given moment.

1.1) Does that mean that beauty is subjective?

Yes and no. The definition above does imply that beauty is not fully “objective” and should not be seen as a property of objects. Instead it is a property of the relation between you and an object. We could call that “subjective,” but that’s also an unsatisfactory term. Many things are almost universally good (among humans or sentient life) and therefore can be described as objectively beautiful.

A good example is novelty: it’s almost always useful to obtain new information, so we’re likely to perceive things we haven’t seen before as beautiful, unless they also have undesirable characteristics. And once the novelty wears off, and there’s no new information to be gained, we may stop perceiving beauty, unless the thing has other desirable characteristics.

1.2) Why does the ability to perceive beauty exist at all?

It seems plausible that our bodies evolved the perception of beauty as a way to pay attention to things like new information, unusual patterns, healthy mates, unspoiled food, dangerous predators, and so on. There are many “subspecies” of beauty, like cuteness, sexiness, and elegance, all emphasizing different ways things can be good.

It’s important to realize that this is not a fully conscious process. We often don’t immediately know why something feels beautiful, unless we take time to think about it.

This article from Wired contains some of the best encapsulations of beauty that I’ve come across, describing it as “a particularly potent and intense form of curiosity” and “a motivational force that helps modulate conscious awareness.” This essay by Kevin Simler is another great exploration of beauty as an evolutionary positive-sum game between, for instance, flowers and pollinators, or among humans.

1.3) You use the word aesthetics a lot. What is it?

“Aesthetics” is a fairly vague term that can refer to the philosophical study of beauty, or to abstract concepts like “style” or “culture.” In this essay I’ll use the word to mean, roughly, a deliberate effort at using beauty to maintain a coherent and recognizable style.

The word “deliberate” is important: it distinguishes my definition from the sense in which everything can be said to have an aesthetic just by virtue of existing, even if there’s no conscious attempt at maintaining it. A house in which no one put any effort at decoration doesn’t have an aesthetic in the definition used here.

Aesthetics, therefore, are a way to inject some awareness into the mostly unaware mechanisms of beauty.

2) All right. So. Why should we care about aesthetics?

The main reason to care about aesthetics is that beauty is a major source of moral intuitions. Moreover, with three caveats that I’ll get to in a moment, it is a particularly robust source of moral intuitions because it is never fully wrong.

Recall that beauty is an extremely general mechanism to pay attention to good things. Therefore, when you perceive something as beautiful, it is always because there is some good to be obtained from that thing, whether that’s satisfying a basic biological need like eating or mating, or something far more abstract such as novel information or a vague and pleasant feeling of familiarity.

Beauty is not a perfect moral signal, but it is a strong one, with the potential to play a large role in ethical decisions. That’s why it’s important to pay attention.

2.1) Okay, what about the caveats?

The first and most important caveat is that we always have diverse and contradictory needs and desires. Often two things are both “good” and simultaneously in flat contradiction with each other. So while beauty is never wrong about identifying goodness, it may very well point towards a kind of good that we’d deem less important than another good.

The second caveat is that good is pretty much always mixed with bad. You may get a valid aesthetic reaction to something because it is good in some sense, but that may also hide valid reasons to dislike it. (And vice-versa: you may get an ugliness or disgust reaction that hides something good.)

The third caveat is that there’s no guarantee that goodness can be perceived and therefore cause beauty. Beauty always points to something good (and ugliness always points to something bad), but the converse is not true: something good isn’t necessarily beautiful (and something bad isn’t necessarily ugly).

For example, imagine a beautiful painting, for sale at $200. My aesthetic appreciation may incentivize me to spend the money to buy it. But there are many other ways to spend $200, not all of which elicit the same aesthetic reaction. I could donate to a bland but effective charity that I consider to be better even though it sends a weaker aesthetic signal.

2.2) These sound like important caveats. Shouldn’t we just reject aesthetics as a source of moral intuition, then?

Well, you can try. I would argue that you are almost guaranteed to fail, and will make matters worse in the process.

Aesthetics are not optional. We are always sensitive to beauty, whether we like it or not. This would perhaps not matter too much if humans couldn’t manipulate aesthetics to achieve our goals, but we obviously can. There are people — in increasing order of negative connotation: artists, marketers, and propagandists — whose job it is to use beauty in order to influence others. It’s impossible to avoid such influence entirely, but you can resist it to some extent by being aware of it.

Furthermore, morality — the rules of what is good and bad — is an extremely difficult topic, as I’m sure most effective altruists are aware. All theories of ethics run into problems sooner or later, and it seems almost impossible to construct a moral framework that completely avoids repugnant conclusions. (Note that “repugnant” is an aesthetically loaded term!) If aesthetics provides a major and robust source of moral intuition, it would be counterproductive to reject it just because it is an imprecise and not-fully-conscious mechanism.

In fact, the semi-conscious nature of aesthetics is perhaps its most important property. Careful, rational, conscious analysis is an important tool to deal with moral matters, but it can only go so far. We never have complete information. We never fully know what we sacrifice in a tradeoff. As I wrote in an essay titled Effective-ish Altruism, “your list of things to optimize is never going to completely match the list of things you care about.”

Beauty happens partially outside our awareness, so it can “catch” things that rational analysis misses. It is not, as the caveats show, a perfect and complete signal, but it is an alternative one, one that can’t be deactivated or put under full conscious control. It is a precious tool in understanding what matters. If you spend some time finding an optimal solution to a problem, and despite all your efforts at optimization, you have an uneasy feeling in your gut, it may be a mistake to ignore that feeling.

Put differently, caring about aesthetics is a way to be epistemically humble. You can never be totally sure that you know what’s best, so you should hedge your bets. You should use alternative methods to figure out morality, and aesthetics are one such alternative — perhaps the best next to rational thought.

3) I can sort of guess at this point, but let’s spell it out: What does this all have to do with Effective Altruism?

The core principle of Effective Altruism is to do good better. “Better” here tends to mean “by carefully analyzing the impact of donations and careers in order to maximize good.” This stands in stark contrast with the more usual ways to make donations and pick a career, which rely on intuition and don’t seek to calculate precisely how much good they cause.

One can view EA as an attempt to deal with caveat #3 above. Many things are good but not particularly aesthetically attractive, such as donating malaria nets to African countries, or dealing with AI risk. So — goes the typical EA argument — we should reject our moral intuitions, aesthetic or otherwise, and coldly calculate the benefits of various choices in order to pick the most effective ones.

3.1) Then you’re about to say that that’s wrong?

Nope! I believe there’s immense value in this core principle. It’s not a coincidence that EA is now getting interest and funding from an increasing number of people: it really is, fundamentally, a good idea. Coldly calculating impacts is not done nearly enough. We do need to use reason and facts to do good. We cannot rely only on intuition.

Evidently, however, many people have problems with that. Erik Hoel says it contains a poison that must be diluted. Kerry Vaughan finds it dehumanizing. The authors of this Reboot essay are “scared” and argue for ineffective altruism. Multiple philosophers have written variations on the theme “against EA.”

I myself have been reluctant to identify as part of EA. The reasons have never been perfectly clear, but I have been suspecting that they are related to aesthetics. I further suspect that a good chunk of other people’s objections could be solved if EA were more aesthetically appealing.

As the movement becomes more widely known (and perhaps will, sometime soon, finally overtake Electronics Arts as the main meaning of the acronym “EA”!), the number of people who have an uneasy feeling in their gut is bound to increase greatly. The easy path for effective altruists would be to dismiss this concern: those people have simply not done the cold impact calculations. That would be a mistake. The uneasy feeling points to something real, and carries important information. The epistemically humble position — which is the difficult one — is to take it seriously.

3.2) What, then, is your main criticism of Effective Altruism, stated clearly?

To make everything as transparent as possible, let’s summarize everything so far in point form. The first premise is:

EA tries to maximize good.

Most people who try to “maximize” anything do so through careful, rational analysis.

But careful, rational analysis is never perfect, especially in the realm of morality. Effective altruists know this, and generally seek to be epistemically humble.

The second premise is:

Beauty is an imperfect but powerful signal of good.

It works semi-consciously, which allows it to capture things that rational analysis misses.

Therefore:

To achieve epistemic humility about moral matters, effective altruists should take aesthetics seriously.

This includes investing some time in resources into EA’s own aesthetics (how it presents itself to the world) as well as taking into account the aesthetics of movements and organizations it interacts with (i.e. the aesthetics of potential causes to support should be considered in addition to their more legible characteristics).

And yet:

EA does very little of that. It doesn’t do nothing — there is some amount of art, storytelling, design, etc. in the community — but it cares or appears to care about aesthetics far less than many other movements as well as for-profit companies.

As EA grows, the lack of aesthetics will prove a significant hurdle. It will empower opponents, weaken EA’s effectiveness, and make it lose influence compared to other movements.

To conclude:

It is now time for EA to make a real effort at aesthetics without reneging on its core principles.

4) Great! What do you suggest, concretely?

In the spirit of epistemic humility, I wouldn’t claim to know how exactly EA should do aesthetics. But we can brainstorm.

A starting point is my Guided by the Beauty of One’s Philosophies essay. Read it for more detail, but to summarize it quickly, I identified three main benefits of aesthetics for movements:

Marketing: attracting people and funding to the cause.

Avoiding the misery trap (Michael Nielsen has a good section on this in his critical essay on EA).

Defining EA values and making them legible.

So the first step might be to examine current problems in EA and see if aesthetics can help solve them. For instance, if there’s a PR problem, then we could study marketing strategies of successful movements and adapt them. If there’s a misery trap problem — people feeling burned out and unhappy as part of EA — then we could write posts emphasize that caring about art and beauty is also a way to be a good person, and should not be described as “less-than-maximally-effective.”

4.1) That’s still pretty vague, what else have you got?

Now I’m just going to throw ideas.

Some places have policies where publicly funded construction projects must devote a small percentage of their budget — where I live, it’s 1% — to the integration of public art. In a way, the government overrides the builders’ incentive to optimize their budget, and forces them to commit a small part of the money to aesthetics.

Some readers may be thinking, “Wait a minute, surely this increases construction costs. That doesn’t sound optimal!” Yes. That’s the point. The 1% policy is a small concession to suboptimality — a way to make everyone commit to devoting money to something (art) whose value is illegible. Having the government mandate it solves the coordination problem.

EA organizations that provide funding could adopt a similar policy. If your project gets a $1 million grant, perhaps it would be good if you were obliged, or strongly encouraged, to use $10,000 of the grant to commission a work of art or hold an artist residency.

Funding organizations could also commit to supporting a small number of artists directly. This could take the form of periodic art or storytelling contests, continuously having an artist in residence, or directly commissioning works from artists who seem aligned with EA values. There are good suggestions along these lines in this post. One example from the post worth mentioning is CERN’s artist residency program.

The most basic part of aesthetics is stuff like web design, logos, etc. I don’t think EA necessarily needs to pour more resources in that than it already does — the default minimal aesthetic of the core EA organizations like 80,000 Hours, Open Philanthropy, or the EA forums, does a decent job at the moment. I do think that perhaps EA-adjacent organizations should feel free to explore more intentional aesthetics in their marketing and design.

4.2) Should EA funders evaluate the aesthetics of organizations and projects before they fund them?

Probably not as a core criterion, but it might be a good idea to explicitly consider aesthetics as part of a grant evaluation. Since aesthetics are not optional, how attractive a project appears to whomever evaluates it will always bear upon the final decision, regardless of how careful and analytic they are. It’s better to show awareness of it instead of pretending that aesthetics have no impact.

One idea from a commenter is to use aesthetics as something like a tiebreaker. When it’s not possible to know perfectly which of several charities or projects should be funded based in impact calculations, then go with vibes (and acknowledge that).

4.3) How much of EA resources should we spend on aesthetics?

That’s a central question. I think it’s clear that it shouldn’t be a lot. We definitely do not want EA to become mostly or even substantially about art and aesthetics. There are probably enough non-EA philanthropists who do that already.

Just like the “rule” of donating 10% of one’s income to charity is an arbitrary but good Schelling point, a 1% “rule” of diverting EA philanthropy to the arts seem like a good number to rally around. But it could be something else. The important part is to signal that spending a small amount of resources on aesthetics with illegible value is something acceptable to an effective altruist, even if it doesn’t feel maximally effective in the moment.

4.4) What are some pitfalls to avoid?

The main trap would be to… try to optimize too much.

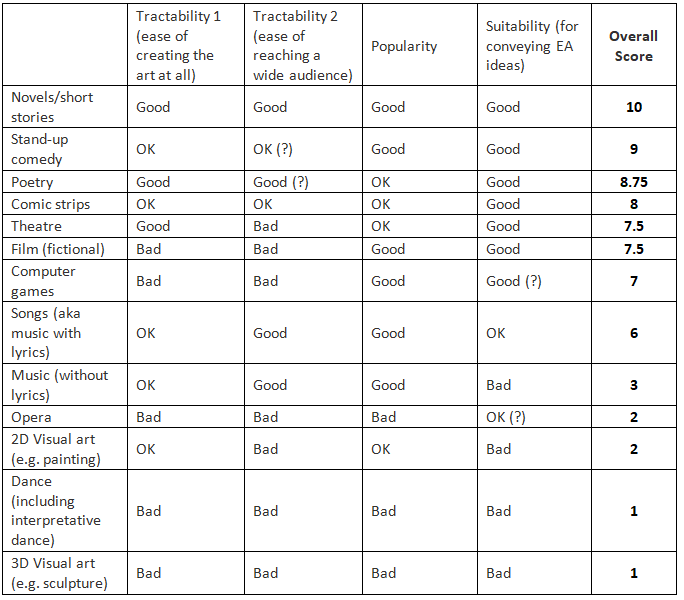

I can totally imagine a scenario in which someone agrees that aesthetics have all the benefits I named and then proceeds to write a long post analyzing the pros and cons of every possible art form. In fact, I don’t really have to imagine it, since this post does basically that. It’s a great post that I mostly agree with! But also, it’s symptomatic of the strong EA tendency to overthink things.

In a similar vein, the people using EA money to fund art could be tempted to pose a lot of conditions to artists. It may seem good to have mechanisms to ensure that the resulting works are aligned with EA, that they paint the movement in a positive light, and so on. I would warn against such top-down involvement. Art, like all creative work from fundamental scientific research to entrepreneurship, is best when it is as free as possible. Trying to control artists would lead to worse art and annihilate many of the benefits of funding them in the first place.

I’m not too worried about this, since EA is clearly fine with people criticizing it. But when money is involved, it becomes hard to resist the temptation of top-down control. So let’s at least be aware of it.

4.5) To sum it up, it sounds like you’re saying that aesthetics is… effective. Right?

Well, yes and no.

Yes, at the abstract, broader, meta level. I do believe that the good that EA will have done after several years will be higher in the universe where it assigned some of its resources to aesthetics, compared to the universe where it didn’t. So in that sense, caring about art and beauty is “effective,” yes.

But again, that is usually not the right way to think about this. At the moment of actually giving a grant to an artist, or setting up a residency program, those abstract considerations on the long-term benefits of creative freedom will almost always be swamped by shorter-term pressure to optimize. There’s always some more legible philanthropic effort you could send the money to instead.

(There’s a strong parallel with science, where it always feels safer and more optimal to fund an established scientist working on incremental research than a smart creative person who doesn’t exactly know what they’re doing — but of course major scientific advances are pretty much always the work of smart creative people who don’t know what they’re doing.)

So yes, caring about aesthetics is effective — but it almost never feels that way, especially not when calculating expected impact in spreadsheets.

5) Any concluding remarks?

The main challenge in thinking about beauty is that its value is illegible. It can never be calculated perfectly. This is not a good match for a movement like Effective Altruism.

But this illegibility — the dance of beauty with our consciousness, its ability to modulate our awareness — is also why beauty matters so much. It carries useful information about what is good.

Only an overconfident fool would reject that and put all their eggs in the basket of rational, mathematical analysis. Effective altruists can do better than this. They can seek to be epistemically humble, to agree that they don’t know everything, to devote a small part of their energy to examining their aesthetic intuitions.

Erik Hoel says that there’s a poison in Effective Altruism that makes it unpalatable to most. He claims that there are only two options: dilute the poison or swallow it whole. But he’s wrong. The antidote exists, and nothing is preventing us from adding a few drops of it to the mix.

I have personally been working through my own concerns with EA recently (particularly longtermism and its many repugnant conclusions). With that in mind, I'm intrigued by the idea of aesthetics as a source of epistemic humility, particularly in the cases of repugnant conclusions. The above article touches on this somewhat but I think that could almost be a separate aesthetics-related critique. So 1) EA should develop its own aesthetic/sense of beauty (main focus of the above article); 2) EA should incorporate aesthetic considerations as a guide to its core optimization calculus (almost like a tiebreaker in cases of uncertainty)