Charting a Course of Study in Neuroaesthetics

And why I think the neural basis of beauty is important 🧠

I once told a friend I was planning to research and write about neuroaesthetics — the neural basis of our perception of beauty.

“Don’t,” he said.

I was taken aback. This is a thoughtful friend, one who’s reflected about aesthetics a lot, and indeed earns a living doing something adjacent to that, and with whom I had several fascinating discussions on the topic. I would have expected that he’d encourage me to dig deeper in what seemed to me like an obviously fascinating line of inquiry.

I decided to dig deeper anyway.

I’ve written before that beauty, for something so ubiquitous and quotidian, is strangely mysterious. We experience it all the time, we debate it endlessly, and yet few of us would be able to really say what it is. We have confused intuitions. It seems acceptable to say that a building or work of art is objectively ugly when others genuinely find it beautiful, which doesn’t make a whole lot of sense: are the enjoyers “wrong” about their own internal state? To cover up the inelegance of such reasoning we invent complicated notions like “taste”; we surmise that beauty is subjective. It is a product of the observer. Yet there is also agreement among subjective aesthetic responses. It’s not random. Some objects are more beautiful than others.

It seems pretty clear to me that beauty really is both objective and subjective. It depends on the properties of an object — its colors, shapes, sounds, patterns, connotations, history, and so on. And it depends on the internal state of the observer: mood, previous exposure, and taste. Beauty (or lack thereof) is what arises from the interaction of these two forces. Remove the observer, and it doesn’t occur.

Here my friend would (I think) disagree: to him beauty is found in the properties of the thing only. A symphony by Mozart is beautiful regardless of who hears it, or whether anyone hears it.

There might be a deep sense in which he’s right. There might be clever arguments to be made based on the nature of consciousness and what it even means to exist without being observed. I don’t particularly want to go there; I just want to point out that some people, upon hearing the symphony, will find it beautiful, and some won’t.

Because it’s Mozart (as opposed to the “symphony” currently being played by the machine parked in front of my house, in the process of grinding dead tree branches), there will likely be more people who get a positive aesthetic reaction than those who get an indifferent or negative one. But all of these outcomes are possible. None of them is wrong. It’s also possible to find the tree grinding beautiful, even if that’s more unlikely. Those likelihoods exist because humans brains react to things in predictable ways — which is also why Mozart was able to compose music that we collectively recognize as “beautiful.”

So we go back to the brain. Somewhere in that gray jelly of neurons, electric currents are triggered when we react aesthetically to something, and only then. If we want to truly understand beauty — and I do — then we need to look into those.

It might be tempting to reject this line of thinking altogether. Beauty, some will say, isn’t meant to be studied like that. Perhaps it can’t be. We can think of all sorts of reasons: beauty might be too culturally mediated. It might be fake, in the sense that there isn’t really a distinct phenomenon that we can study. Reducing it to a physical process in the brain might be an infohazard of some kind, with the scary possibility that understanding beauty too well will lead to less of it.

I reject all of these. Even if beauty is cultural (and it certainly is to a large degree!) there’s still something going on in the brain when you see an aesthetically pleasing picture. I very much doubt that this something can’t be identified as a distinct phenomenon — my perception of beauty definitely feels like a thing — but we don’t know that, and the way to know is to study it more. As for the part where understanding beauty might be bad, I think that’s wrong as a matter of general principle. Understanding mysteries makes the world more wondrous, not less.

My friend’s objection to neuroaesthetics was something else. He simply thinks that neuroscience isn’t a very interesting way to examine beauty. It doesn’t tell us much. Putting a patient in an fMRI machine, showing them images of the Mona Lisa or putting on a Mozart symphony, and detecting some kind of increased neural activity in this or that part of the brain, isn’t super enlightening.

This is true, but I think the primary problem is that neuroscience isn’t advanced enough. We often have no idea how to translate “increased neural activity in this or that part of the brain” into actually useful knowledge. This is even more true when it comes to a phenomenon as general and as poorly understood as beauty.

But neuroscience can still provide useful insights. If most of what we call beauty has a clear correlation with some kind of brain activity, while a smaller part (to take a dumb example, the perception of the color green) has nothing to do with that, then that’s a sign that we should refine our theories and maybe stop considering the enjoyment of green as the same phenomenon as the enjoyment of other colors. I don’t predict this would happen with colors, but it might with more subtle concepts.

I am not in a position to advance neuroaesthetics in an experimental way, but I think there’s value in looking into the existing literature to figure out what we know, since the field is young and largely unstructured. Perhaps eventually I can even contribute a little theory.

Here’s a list of concepts, like so many paths I may take in the future as I explore the topic.

Artistic vs. natural beauty. It seems like a lot of philosophical and scientific effort goes into understanding art, which makes sense: everyone likes art, and art is a big economic activity. There’s even a fancy formal definition of neuroaesthetics that says it is “the scientific study of the neural bases for the contemplation and creation of a work of art.” However, that seems too specific to me. There’s plenty of beauty to be found in nature or non-artistic human activities, and I doubt that there’s a fundamental difference: art is just what happens when people make things with the intention of tapping into our natural instincts for beauty. But studying the exact difference between those might be productive: do our brains react to a human-made work of art differently from a beautiful landscape (or an AI-made work of art)?

Abstract vs. representational art. Abstract art, in a way, is “purer.” Studies focusing on that might be helpful at distinguishing how we react to basic concepts like colors and shapes. Is there a fundamental neural difference with art that represents people or things?

The five senses. When we think of beauty we tend to think of visual beauty. A person is “beautiful” if they’re pretty to look at. But beauty definitely applies to sounds, too (cf. Mozart). It’s less commonly used for smell, taste, or touch, but it seems easy enough to figure out analogs: “tasting good” might be the same phenomenon as “being pretty to look at.” Is it? What happens in the brain when we get pleasurable reactions from the various senses? What about the beauty of not strictly sensory inputs, like stories, math, or behavior? Most interestingly, what is common between them?

Individual vs. collective beauty. Does the perception of beauty happen consistently the same way in the brains of everyone? I assume so, but it would be really interesting if it turned out not to be the case. What if everyone’s neural perception of beauty happened in an individualized way as they grow up? This would give credence to the “beauty is subjective” side of the spectrum. Conversely, if beauty is neurally very fixed, then we should be able to make strong predictions on what is “objectively” beautiful or not.

Beauty for other animals. Can other animals perceive beauty? If they have the same neural activations as us, they might. What is the minimal neural architecture needed? Can a Caenorhabditis elegans and its 302 neurons have an aesthetic experience? Is there a way to tell? Could this have implications on animal moral status?

Beauty for artificial minds. From animals there is but a small jump to artificial minds, which may or may not exist in a meaningful sense at the moment. Can GPT-4 perceive beauty? Is such perception one of the missing pieces before we can call an artificial intelligence truly intelligent? In “The Overfit Theory of Everything,” I wrote:

“And so a true sign of intelligence might be the ability to find beauty in novelty. If an entity didn’t, it would be way too vulnerable to overfit, and as a result be less intelligent than it otherwise could be.”

Is this true? Can we check? Are there potential consequences on whether we can make AIs that are safe and aligned with human values (which often are correlated with what we find beautiful)?

Emotion. It’s obvious that being in a certain emotional state or another influences our perception of beauty. What happens in the brain when we’re afraid, angry, joyful might have some consequences on the parts that react to beauty, too. Or perhaps beauty should be understood as an emotion itself?

Cuteness, elegance, kitsch, and other subspecies of beauty. I wrote about these in a post I called “A Taxonomy of Beauty.” It was a theoretical and speculative essay, but there’s no reason to stop there. Do each of these subspecies of beauty cause the same kind of brain activity, or not at all? Is it a mistake to classify them together?

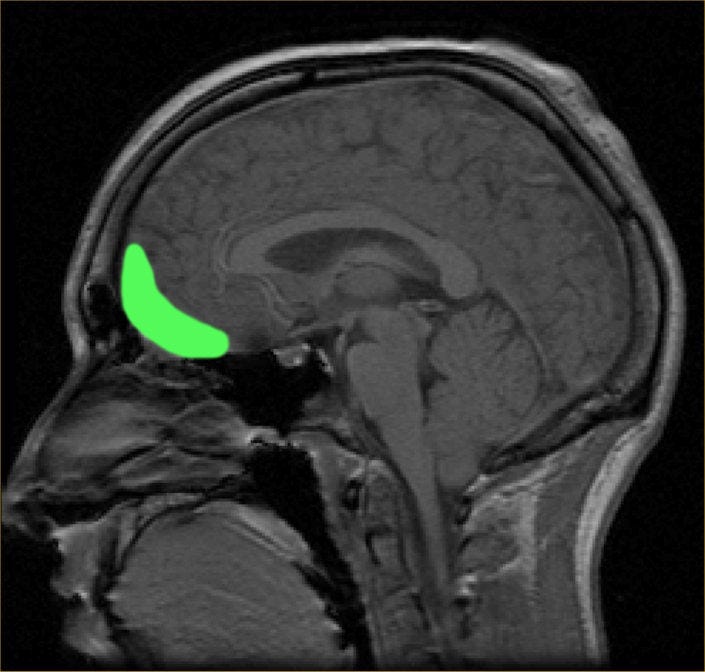

Ugliness. Is the opposite of beauty a distinct phenomenon, or just a lack of beauty? From my early readings (Wikipedia) it seems that it is the latter: the orbito-frontal cortex is simply not activated when we look at something ugly; there isn’t a separate “ugliness center.” I’d be curious to see how this fact interacts with the basic emotion of disgust.

Interestingness and boredom. I have long suspected that beauty is simply a subset of interestingness — specifically, the subset where the interesting thing is also seen as positive is some way. Seems straightforward to check if interestingness is similarly correlated to beauty (assuming some researcher bothered to).

Sex. A very important subset of our usage of the word “beautiful” refers to attraction to other people, which is easily explained in terms of evolutionary biology. But because we care about the appearance of people in a very different way than we care about some random visual (or auditory, etc.) stimuli, we might ask whether this is really the same as general beauty. Are there clues in the brain? This is potentially a fruitful line of research, because, of course, people care a lot about sexual attraction, so a lot has been written.

Ramachandran's eight laws of artistic experience. These are straight from Wikipedia on neuroaesthetics. The eight laws are:

Peak shift principle: We react more to supernormal stimuli, exaggerated lines, etc.

Isolation: An element of a larger whole (a painting, etc.) is often more aesthetically pleasurable when it’s easily distinguished from the other

Grouping: There’s enjoyment in grouping together some elements as a single entity

Contrast: We notice abrupt changes more easily and they can therefore be more pleasing.

Perceptual problem solving: Having to do a bit of work to understand what we look at is more enjoyable than obvious. See also “classic style” in writing.

The generic viewpoint: We prefer images where we can assume an infinity of viewpoint. (I’m not sure I get this one.)

Visual metaphors: Deep meanings between apparently unrelated visual elements are fun.

Symmetry: From biology, noticing symmetry is good both for detecting danger (predators are often symmetric) and lack of disease in others.

I’m not sure these eight concepts make more sense than other frames; they might be an example of why neuroaesthetics is often criticized for making grand claims. But they’re potential building blocks for more solid theories.

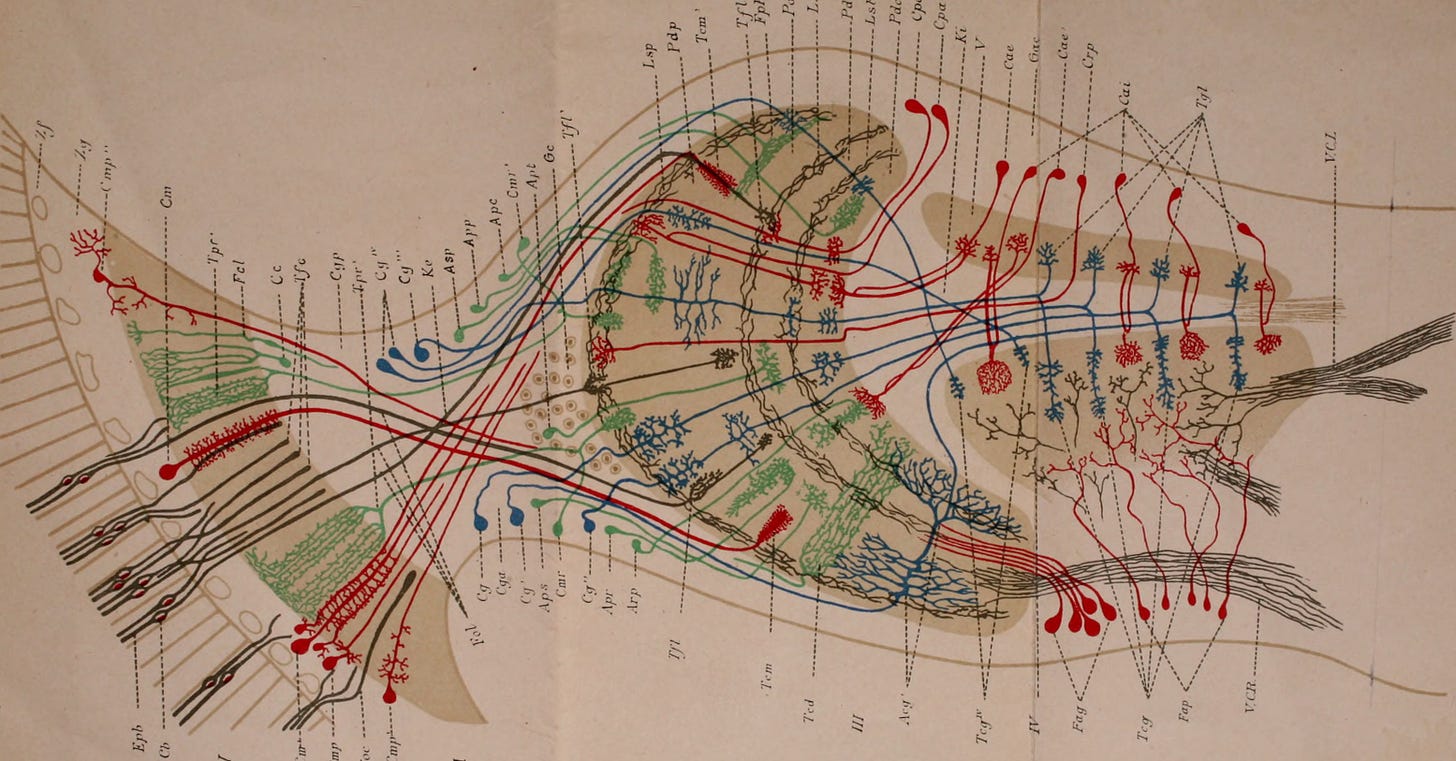

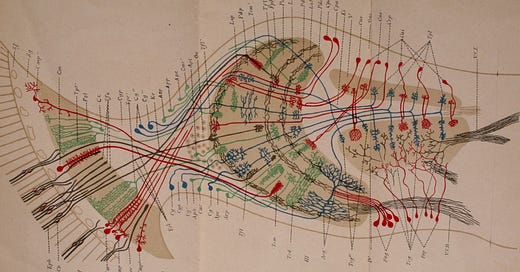

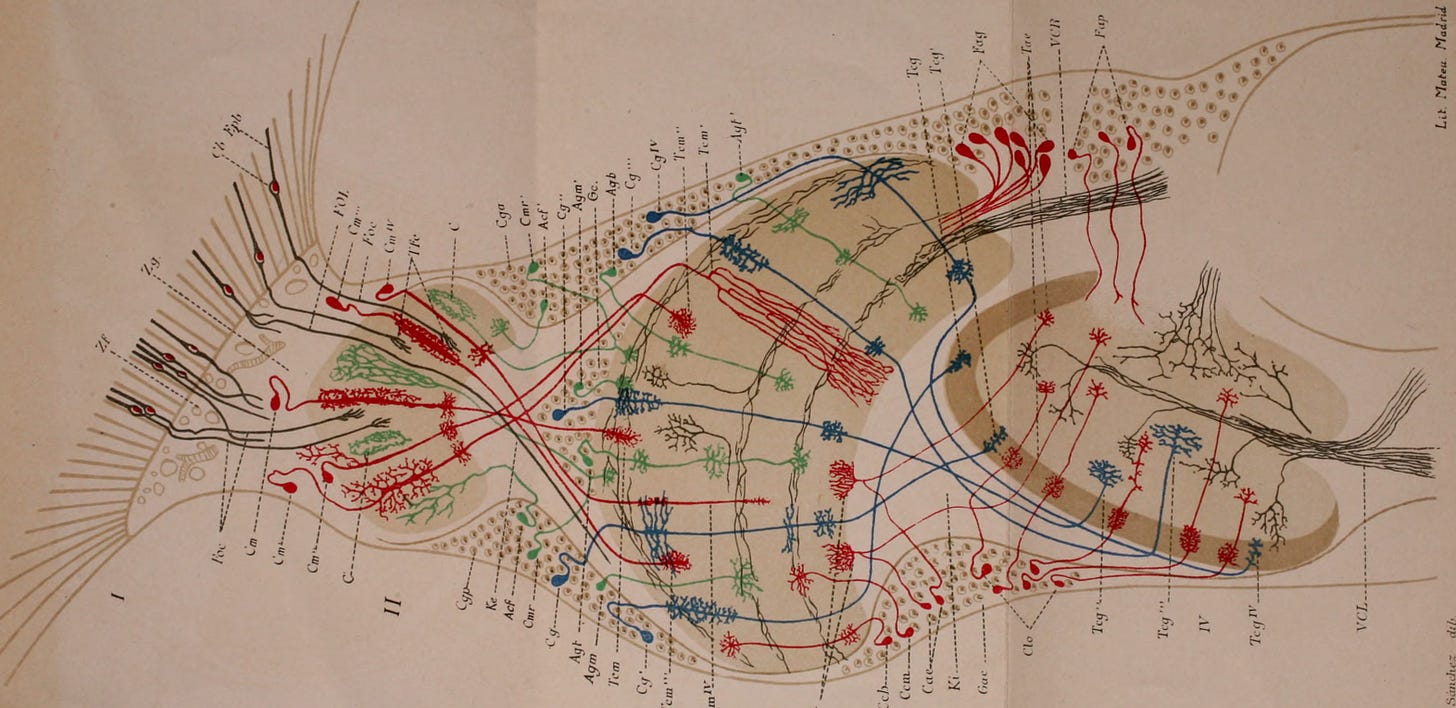

The aesthetic triad. Also from Wikipedia: some researchers believe that aesthetic experiences “are an emergent property of interactions among a triad of neural systems that involve sensory-motor, emotion-valuation, and meaning-knowledge circuitry.” This suggests that the answers are going to be highly complex, as you’d expect from something with such a general scope as aesthetics.

Well, that’s a lot. At least this list makes clear that my original ambition of summarizing the whole field of neuroaesthetics in one quickly written blog post was totally foolish.

Ultimately I’m most interested in this as a way to perhaps bring an original viewpoint in the current AI debate. We’re at the stage in history where, for the first time, we might be creating truly intelligent yet alien minds. We don’t really know, in a deep sense, how they work, just like we don’t really know how our minds work beyond the simple mechanics of neurons. Because beauty seems so foundational, I suspect it might provide some clues that could be useful.

I don’t know what clues yet, of course, and there’s certainly a danger in theorizing too much, to the point of creating entirely fictional ones. At least neuroaesthetics provides a grounding of some sort, a way to distinguish between good and bad ideas using reality. I’m excited to dig deeper soon.

Taken in the larger sense "neuroaesthetics" is the study of the neurological basis of perception, and of course, useful for medical and other reasons. In the sense you mean - studying art and beauty - it has been a going discipline for a long time (at least since the late 1980's), with its own journals, conferences, etc. Definitely publishable - anything that begins with "neuro'" has been publishable in philosophy for a long time (cf. "neuroethics"). For me, I can't even imagine, much less have I seen, a theory or established claim in this field that strikes me as philosophically interesting. It doesn't mean there is nothing to discover - I'm sure that if the "rule of thirds" in photography is a good general principle for creating attractive images, there is some neurological background that helps explain this. But I am interested in the phenomenon itself, how it relates to other aspects of photographic art, why it is a general but not universal guide, etc. The answer to these questions is never, for me, going to lie in neurological facts. Add to that the fact that the alleged neurological basis of any mental phenomenon is almost always defeasible (cf "mirror neurons"). There may be a neurological basis for both Kantian and utilitarian ethics too, but Thompson's study of the trolley problem gives us insights into our ethical intuitions in a way that I can't see any neurological study coming up with. I've read half a dozen books on consciousness by cognitive scientists and neuroscientists and they don't even have anything enlightening to say about that allegedly biological phenomenon. Emotion is a more borderline subject - I'm not sure it belongs in philosophy at all, so I wouldn't be surprised if neurological studies were more useful than philosophical ones.

Perhaps your friend who said "Don't" simply wanted you to focus on something that might be considered philosophically important rather than seeing your work get buried in a million other neuro-this and neuro-that studies. Reading Lessing or Hegel or Mary Mothersill on beauty is always going to be more helpful than reading neuroaesthetic studies.

Consider reading over the propositions in the neuroscience section of this paper on Harmony: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S240587262200003X

And this paper on resonance, written with several neuroaestheticians ;)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9097027/

Love your posts, always excellent.