Ethics and the Complexity of Models

With a title like that, absolutely no one will read my article 🚋

Most philosophers agree that there are, broadly speaking, three kinds of ethics — three big ways of deciding what’s good and what’s not. There’s deontology, where an action is considered good if it respects some sort of established moral rule. There’s consequentialism, where an action is judged according to its outcomes: a good action is one that maximizes some measure of goodness. And there’s virtue ethics, where the focus is on people rather than actions; a good action is one that is consistent with being a virtuous person.

Part of me likes this holy trinity. It’s elegant. But another part of me has long suspected that it’s a bit meaningless. It’s too easy to rewrite each view into any of the other two.

If you were following some deontological rule and you began to notice it kept having terrible consequences on yourself and the people around you, you’d start asking questions — and suddenly you wouldn’t be a deontologist anymore, but a consequentialist. Or you might become a virtue ethicist if your steadfast deontological rule made you feel like a virtueless asshole.

If instead you started out as a consequentialist, calculating the pros and cons of everything you do, you’d quickly realize that you can’t do this for everything, and come up with a number of heuristics — rules, or models of virtue — to actually function in society. Deontological rules and virtues both require some justification, and it seems very dubious to completely divorce those justifications from the the rules’ or virtues’ consequences.

And if you were a virtue ethicist, how exactly do you determine what is a virtue without resorting to consequences or rules?

In a sense, it’s not exactly surprising or strange that the three ethical views often look similar — they all have to deal with the same human morality, and they all involve rules, consequences, and virtues. The differences between them only come out when discussing edge cases and thought experiments, like the trolley problem.

Yet many smart people seem to think that the distinction between the three is highly meaningful. It might just be that they’re philosophers and are pedantically obsessed with edge cases and thought experiments, but it’s probably safer to assume that I’m missing something.

Recently something clicked, and I feel I have a potentially satisfactory answer. The difference between the three views is the complexity of the models they rely on.

Deontology has the simplest model. Everything is either right or wrong according to a rule, or set of rules. Depending on the deontological theory we’re dealing with, those rules might take only a few words. Kant’s categorical imperative is simply, “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.” You can write entire books about it if you want (and Kant sure did!), but at its core it’s a very simple thing. Religious deontology also tends to be of the form “follow these approximately 10 commandments and you’ll be fine.” At most your deontology will be a couple books, e.g. codes of laws or religious doctrine. Once you’ve learned the rules, you can follow them relatively mindlessly.

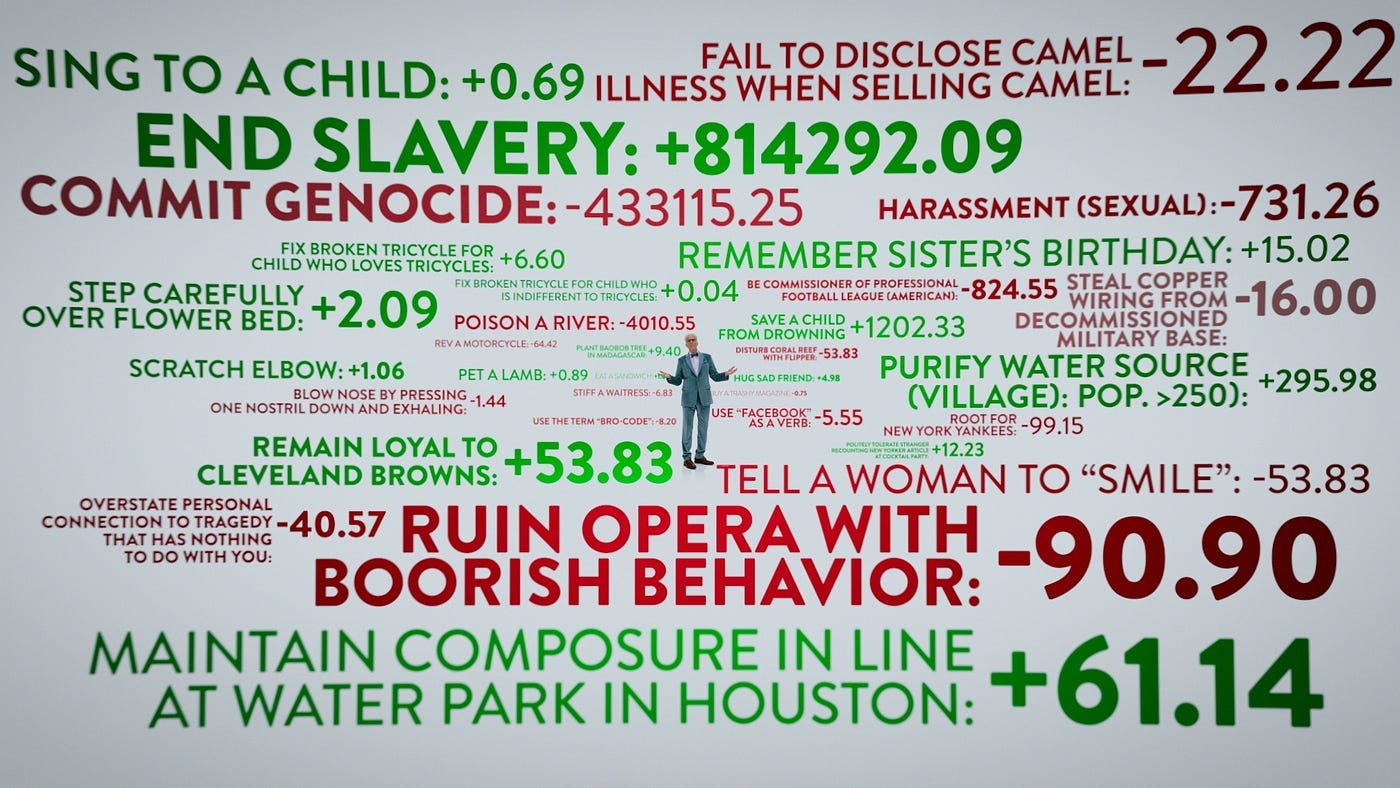

Consequentialism implies a much more complex model. It initially seems deceptively simple: just maximize something you care about, such as well-being or happiness. But to be able to maximize that, you need to know a lot about the world. Everything causes a bunch of consequences, some of them predictable and some not, not to mention that the consequences have consequences of their own, and so on. This can be much better than using simple rules, since it allows you to consider special cases. On the other hand, true, full consequentialism — the kind that doesn’t reduce to a deontological heuristic — essentially requires omniscience. You might settle for an imperfect yet reasonable approximation of that, but even then, it’s a lot of work.

Put this way, deontology and consequentialism contrast in interesting fashion. On one side, the simplistic, dumb, irrational view where you just have to follow the rules; on the other, the view that embraces the complexity of the world, and says we can use intelligence and math to become more ethical. Or — on one side, the wise, distilled morals from past generations, easy to teach and follow; on the other, the hubristic, dangerous tendency of those who believe they can calculate and control everything. Depending on your sensibilities, you can decide which of deontology and consequentialism is the thesis and which is the antithesis.

And what about virtue ethics? I like to view it as the synthesis: it’s the view that accepts the complexity and intractability of the world, yet doesn’t try to condense it into a simple model. Instead, it relies on existing models.

To be virtuous is to act like a virtuous person. A virtuous person necessarily has a good model of the world and of morality, presumably acquired through their education and experiences — but the details don’t matter too much. Once you’ve identified a paragon of virtue, you can just seek to act the way they would. Of course, your own personal model of that person is necessarily imperfect. And of course, in practice you’ll want to have multiple paragons of virtue. But at no point are you building a model yourself. Thus you avoid the pitfalls of being either simplistic or hubristic.

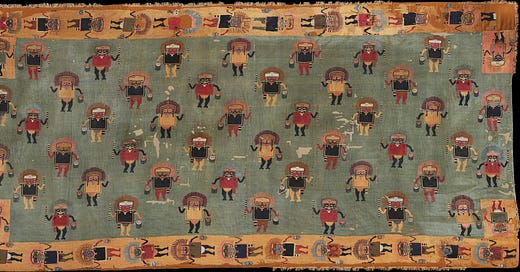

For virtue ethics to work, there must be existing models; we need to know what virtues are. In a virtual environment with no preexisting history, that wouldn’t be possible, and you’d need to go back to either rules or consequences. But fortunately, in the real world, there has been a lot of accumulated experience — sifted through the mechanism of cultural evolution. Virtue ethics is the view that deliberately taps into that.

I wouldn’t necessarily conclude that it is superior to the other two approaches. But if I’m honest, part of me does think so. I’ve never been very convinced by deontological theories, probably because it’s always easy to see them fail in corner cases; and consequentialism, though attractive, always leaves me with a weird aftertaste. Virtue ethics offers a way out — but that, in itself, isn’t sufficient to embrace it. It has to be truly justified.

I think that my point about models does a substantial part of the justification work. Now I understand a little better why virtue ethics feels right to me. It fits with some of my other views, for instance that aesthetics is a useful alternative signal to reason in determining what’s good (we can view aesthetics as being a proxy for virtue). Or that cultural evolution is a major, if not the main force in explaining human behavior, by encoding extremely complex norms through adaptation over generations.

This line of thinking also reminds me of a small book by a Quebecois philosopher I read and reviewed1 a few years ago. It argued that to make ethical AI systems, we might want to rely on virtue ethics rather than the other two views. We should teach robots to look for paragons of virtue rather than encode moral rules directly (deontology) or tell them to maximize some objective function through reinforcement learning (consequentialism). That seems broadly right, and in line with the Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback approach that has become popular in AI in the past few years, as well as recent projects like Democratic inputs to AI and Meaning Alignment. We’re not trying to specify morals into code; we’re asking the AI to learn it from existing people who already have developed their models throughout their lifetime.

Contrary to what this image says, my ideas about model complexity certainly don’t solve everything. They certainly don’t allow us to discard deontology and consequentialism. In fact I still suspect that consequences are somewhat more important than virtues. Also, maybe I’ll learn more about virtue ethics and change my mind. Who knows! But at least I feel more clarity now, which I guess is pretty important when it comes to ethics.

The book is called Faire la morale aux robots, by Martin Gibert (2020). I reviewed it here (in French).

I'm not sure Kant's rule (and its companion in idea, the Golden Rule) are actually deontological. Such a rule feels different in kind from "thou shalt not commit adultery." It actually is a rule that looks at the consequences of one's actions--will the choice you make be something you can take yourself if that choice is applied to you? It doesn't depend on any model of virtue. So it seems to be in its own category. Are there really only three categories for looking at ethics?

It has its limits. In the parking/bike lane example mentioned elsewhere in this discussion, the decision maker's use of it can depend on whether s/he cares about parking. "I wouldn't mind losing parking since I don't drive" slants the decision to bike lanes. But the broader question might be framed as "would you agree that a long-standing situation (that you relied on to make your choice of where to live) should be overturned for the greater good of people who didn't make choices based on that reliance." That might lead to a different application of the Golden Rule by even those who don't drive.

Seems to me that the whole conundrum shows the limits of using models to describe anything complex without taking into account the boundaries of the model.

I have a silly example, but it is something that got me thinking about freedom/ethics in the world and has been with me ever since. I'd want to see whether this contributes anything to our conversation.

So you've probably have witnessed this in gradeschool: little Sally wants to use the restroom. She asks the teacher "Can I use the restroom?" she inquires of the teacher. "I don't know, Sally, *can* you?" says the teacher. So Sally realizes what she really means is "may I". The ability (can) to do then is only hindered by some obvious obstruction (like something physically barring Sally from just walking to the bathroom). In a world absence of ethics there is just pure ability (can) in the world, especially when there is nobody else involved. You get other people involved and then after you have determined you could do the thing, the next thing, ethically, is whether you ought to do it or not.

Determining whether Sally is allowed to use the restroom involves considering both deontological and consequentialist elements.

For example, asking if she may use the restroom rather than can acknowledges there are rules or norms (deontology) governing her freedom in this situation. Simply being able to use the restroom physically (can) differs from having permission (may).

However, the rules around giving children permission also take into account consequences. For example, allowing breaks prevents accidents but also ensures learning isn't unduly disrupted.

Most real-world ethical decisions involve balancing different considerations in a nuanced way. You may say in this situation that both the rules (deontology) and outcomes (consequentialism) matter.

Virtue ethics, as you point out, provides a framework for navigating complex situations by drawing on accumulated wisdom and examples of virtuous behavior over time. Determining what response is virtuous involves understanding both norms/rules and consequences.

So let us say that Sally passes step one that she use can physically go to the restroom without obvious obstruction, but she could bypass step two by sneaking out of the classroom and sneaking back in. If she were successful at that would a consequentialist be concerned here? Maybe, until one day she gets caught then Sally realizes it was more trouble than just asking and dealing with whether she was allowed to or not.

She would recognize there are norms/rules around asking permission that reflect virtues like obedience, respect for authority, and orderliness. Simply going to the bathroom without asking risks consequences like getting in trouble if caught, which could undermine virtues like honesty and responsibility. Sneaking away risks even more negative consequences from getting caught, being very much at odds with virtues of integrity, trustworthiness, etc.

A virtuous person's model in this case would likely be one who follows the rules/norms, even if it means a brief delay, as that aligns more closely with being a good student and trustworthy individual.

Sally's goal under virtue ethics wouldn't just be avoiding permission, but acting in a way that exemplifies virtues overall based on her understanding of role models and social norms. Virtue ethics doesn't just consider rules/consequences in isolation, but how following or subverting them impacts one's character and virtues holistically. There are rarely simple or single-factor answers when real virtue is at stake.

The bathroom scenario Sally faces illustrates how virtue ethics navigates complexity better than other approaches. While she could physically access the bathroom, simply following her ability (can) ignores norms of permission (may). Granting permission considers outcomes like learning disruption. However, virtue ethics goes further.

As you note, virtue ethics relies on internalized models of virtuous behavior. In Sally's role as student, she models obedience and respect for authority by asking first. Though a brief delay, this aligns with virtues of responsibility and orderliness. Alternatively, sneaking away risks negative consequences of getting caught undermining honesty and trustworthiness.

By drawing on accumulated wisdom of virtues, Sally recognizes the most ethical choice exceeds rules or consequences alone. It requires acting consistently with her virtuous role to maintain integrity and trust over self-interest. This holistic perspective is why virtue ethics provides the most satisfactory framework in navigating real-world dilemmas with nuance rather than simplistic models. Sally's scenario demonstrates virtue ethics' superiority in balancing complex factors.

The obvious limitation with my example is of course we're talking about a grade school kid with a brain not yet fully developed, but at that age I think we all had some idea of these ethical principles and consequences to actions, I just did not have the vocabulary to describe them as I do now and as we interact with the world we gradually learn more.