I participated in the Astral Codex Ten book review contest thrice. The first time I wrote about the history of the scientific journal Nature and became one of the fifteen finalists. The second time I wrote about Jane Jacobs, cities, and separatism, and somehow I was a winner, although barely: I got third place, and only because Scott Alexander, who runs the contest, disqualified his own entry, which readers had voted as the winner. The third time was this year; I wrote about ancient Egypt and the religion of pharaoh Akhenaten. This won me no spot on the shortlist, which is just as well — it’s probably better if some other writers get the visibility instead. Still, somebody in the comments below the finalist announcement said this of my review:

I'm pretty sure that was actually by Scott. It was funny and clever and maybe suffered from not having any great idea to reveal (and it also suffered from me knowing this stuff already) but there was a lot of interesting info and I got a feel for how little data we've got to deduce anything about the period and how shaky the deductions can get.

Not gonna lie, being mistaken for Scott Alexander’s “funny and clever” writing feels pretty great.

I’m going to post that book review next week, probably. But today I want to discuss the contest itself, because it is, on its own, an interesting cultural artifact.

I’m writing it as a How To Win guide, which I guess I have a little bit of expertise in, though I’m afraid I can’t make any guarantees as to whether any of this will help you win. Maybe, if you’re very lucky, you can get a third place, by a hair.

I. The (Very Basic) Basics

The Astral Codex Ten book review contest barely has any rules. This is the bulk of them, as of the 2024 edition:

Write a review of a book. There’s no official word count requirement, but previous finalists and winners were often between 2,000 and 10,000 words. There’s no official recommended style, but check the style of last year’s finalists and winners or my ACX book reviews (1, 2, 3) if you need inspiration. Please limit yourself to one entry per person or team.

(Plus a lot of words about making sure you submit a Google Doc that has the correct sharing permissions and no information allowing readers to deduce who you are.)

Two of the four sentences in that paragraph are explicitly anti-rules: you can write however many words you want, and in any style you want. The fourth sentence is an actual rule: can’t submit multiple entries. And then there’s the first sentence, “Write a review of a book.”

It would be reasonable to infer from this sentence that to win, or at least to enter, you need to write a review of a book. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Okay, I’m exaggerating a tiny bit. If your review is selected as a finalist, it’ll be published under the title “Your Book Review: BOOK TITLE”, so you do need a BOOK TITLE to put in there. And readers will expect BOOK TITLE to be discussed in the piece. But beyond this, you can basically do whatever you want. You can, for example, write a review of an imaginary book.1 You can write a review of multiple books; my 3rd-place winning entry was one such. You can write something that’s about a book but isn’t really a review, or a review that isn’t really about the book. You can — in fact, as we’ll see, you are almost expected to — sort of review the book, and then use it as an excuse to write a whole essay about related ideas that are decidedly not in the book.

Still, I would recommend not being too experimental. Because the way the contest is judged in the first round is that the 150 entries or so are put into a bunch of public Google Docs, and then readers of the ACX blog are asked to sample from them and give them a 1-10 rating. So the main success criterion is whether ACX’s readership like your work. (Scott Alexander himself has a lot of discretionary power since it’s his blog, of course, but it’s unknown to what extent he uses it or even votes on his own contest.)2

The second round, to select winners out of finalists, works similarly, except that finalists are posted to the main blog and get a lot more visibility. Then anyone can vote and also participate in a prediction market because of course there’s going to be a prediction market for something ACX-related.3 Ultimately it’s still whatever readers like, though. There are no predefined criteria.

So you have a lot of freedom — but if you truly want to win, you have to exercise it wisely.

II. Choosing Your Topic and Book

The book you pick can be about anything. Past book reviews have been about anything. Past winners have been about anything.

Actually, let’s look at those more closely. There’s a handy database made by a member of the ACX community that lists all the book reviews ever entered in the contest. Filtering by the “winner” tag, we get 12 winning entries (1st, 2nd, or 3rd place) over the years. They’re about (see footnote for the titles):4

Economics and social theory (winner in 2021)

Memoir, poverty

Greco-Roman medicine

Geopolitics

Anthropology and global history (winner in 2022)

Chinese history

History of music, human biology

Nuclear physics

International politics

Education (winner in 2023)

Fiction, allegory of nazism, aesthetics

Economics and politics

(We could also consider Scott Alexander’s self-disqualified Njáls Saga review, and therefore add Medieval Icelandic history and law to the list.)

Most of this is non-narrative nonfiction, but there’s a memoir by George Orwell and an allegorical fictional work by Ernst Jünger. I notice a fair amount of history in various flavors, and several books about, broadly, “society.” Less common, but present, are books about science, art, and education. I’ll let you figure out the topics that have no representation at all among winners.

Another interesting dimension of books is their publication year. Unlike your typical journalistic book review, books reviewed on the contest needn’t be recent. For the same list of winners, the publication years are 1879, 1933, the 2nd century, 2020 and 2018, 2021, 1981, 2014, 2018, 2017, 1997, 1939, and 1984 and 1980 (and Njáls Saga dates from around 1270-1290). Half are 21st century, a few are from the 80s and 90s, and several are older, all the way to antiquity.

Sadly, none of this shows any clear trend you can follow to win your prize. Maybe you’ll have a better shot with a book about some combination of economics, politics, and history, but it’s hard to say. What actually matters, instead, is that your book and topic are interesting. This is, of course, frustratingly vague. What will the ACX readers find interesting? One way to figure it out is to read the blog and some of the comments: build a model, even an imperfect one, of what the community wants. An even better way is to already be the kind of person who likes the blog, read many books, and review the one you found the most interesting.

But if I were to attempt an actual answer, I’d say that the contest favors topics that are broad. Books that give a glimpse into the nature of the world as a whole. Hence the winning The Dawn of Everything entry; or the The Educated Mind one, which is ostensibly about education but dives deep into philosophical truths. Of the three entries I submitted, the most successful one had a theory of cities and countries that applies to the entire world, as opposed to the more specialized topics of scientific publishing or ancient Egyptian religion.

Or maybe that’s not quite right — the book can be highly specialized, like On the Natural Faculties (on the practice and philosophy of medicine according to Roman Imperial-era physician Galen) or The Future of Fusion Energy (on, unsurprisingly, fusion energy). Maybe the book can be about something narrow, but what matters is what you do with it, i.e. show that it can lead to a far more general insight.

Which brings us to our next point. You have picked a book, read it, and found it interesting enough to spend hours writing a review of it. What should you actually put in that review?

III. The Content: What Exactly Is a Book Review, Anyway?

People have all sorts of opinions on what a “book review” should be. At one extreme, a review can be a single integer: a score between 1 and 5. At the other extreme, a review can be a sprawling essay that is longer than the book itself and only tangentially related to it.

I very much doubt you can win with a review that is a single integer. I think you can win with a sprawling essay that is longer than the book itself and only tangentially related to it, but that’s hard. So most likely you’ll want to fall somewhere in between the two extremes. But even then there are lots of distinct opinions on the idealized book review. Some readers rate highly the reviews that make them buy the book — which implies that the review should be positive and not too revealing. Others want the exact opposite: if the review is so good that it makes reading the book unnecessary to grasp its insights, then that’s a win, especially if the book itself isn’t a fun read.

In practice, I think it’s reasonable advice to say you should balance the following three elements: a summary of the book, a critique of it, and your own original ideas. Lacking too much of any of them will doom your review to the land of non-finalists:

Without a good summary, readers will just be confused. You picked this book because it was interesting in some way, so we expect you to show that! You might be able to skip the summary if you’re reviewing a very well-known book, but even then, I wouldn’t recommend it.

Without a critique, it isn’t really a review. We want to know what you thought of the book!

Without original ideas, you can have a very competent book review, but nobody will be particularly impressed. And you do need to impress if you want to be shortlisted. I think this is what doomed my submission about ancient Egypt: there wasn’t any grand insight to be made (I tried to find one and there just wasn’t any). So while my review is informative and “funny and clever,” it’s missing that extra spark, so to speak.

This last point is important. Original ideas aren’t necessarily expected of a traditional book review. But people don’t read Astral Codex Ten because they like books; they read it because they like big ideas. The book review contest is just an excuse to discuss those. It’s a good excuse — books have been known to contain big ideas on occasion — but some contestants make the mistake of thinking this is secondary. Even I made that mistake, and after having previously won 3rd place!

Well. It wasn’t a mistake per se. I was actually hoping, and expecting, to come up with some mindblowing insight from reading about pharaoh Akhenaten’s sun cult. But the more I read, the more I realized that wouldn’t happen. I decided to write the review anyway, because it’s a fun topic, and I didn’t care very much about trying to be a finalist this time. But if you wanted actual advice to win, I’d tell you to write a review of a book that genuinely gave you a mindblowing insight when you read it. Otherwise you’re starting with the deck stacked against you.

Interlude: Would It Be Better to Drop the Book Pretense and Just Call This an Essay Contest?

If what matters is the big idea behind the book, and if there aren’t really any criteria for how “book review-y” entries need to be, should this be a more generic contest?

I mean, if Scott wants to, sure, why not. I seem to recall he considered the idea for this year (and evidently decided against it). But I think it’s good if the contest remains ostensibly about books, for a few reasons:

Having constraints is good! Even if, as we’ve seen, the constraints are light, being prompted to write a book review as opposed to anything is a good way to get the creative juices flowing.

It’s also a good prompt to read an interesting book and pay really close attention to it. When you read a book about Nature’s history, Jane Jacobs’s views on cities, or Akhenaten’s religion, you can learn a lot of stuff, but you also forget many of the details. When you write a 9,000-word book review on the book, you truly learn those details and can then forever enjoy a level of mastery on the topic that almost no one else has.

For readers, a well-written book review is great to get acquainted with books most of us would never read, including obscure but interesting ones like On the Natural Faculties.

In a way, an ACX book review is almost… like a specific genre of essay? One that is distinct from “book reviews” in general, and also doesn’t really exist anywhere else. A generic essay contest would get essays written in all sorts of genres, which is nice, but “essays in all sorts of genres” is already a good description of the blogosphere. Meanwhile there aren’t any other places where you can go read ACX-style book reviews, so it’s good that the contest provides more of that.

IV. Length: Take Advantage of the Non-Existent Word Limit

Each time a new contest is announced, some people say that Scott should institute a word limit. Last year some of the reviews were really out of control!

Each time a finalist review is posted on the blog and it’s more than a few thousand words, some people say that Scott should institute a word limit. Come on! This review is basically a book in itself, this is getting ridiculous!5

Each time voting concludes and the winners are announced, it turns out that the most popular one is by far the longest. The review of The Dawn of Everything had 9,500 words. This was remarkably short for a winner: Progress and Poverty had 20,600 words, and The Educated Mind, which won last year, had almost 25,000.

(For reference, a typical book might have between 50,000 and 80,000 words, and the blog post you’re reading, about 4,000.)

So the people complaining about length turn out to be hilariously wrong. The readers, they love long reviews. We have to remember that we’re talking about Astral Codex Ten here — a blog already known for lengthy but extremely well-written walls of text. Know your audience!

(Also, maybe Scott should revise his statement that “previous finalists and winners were often between 2,000 and 10,000 words.”)

Should you aim for 20,000 words? Maybe not, since very long pieces can be risky: they take a lot of both time and skill. Captivating people’s interest for the equivalent of 100 pages isn’t easy. But I think it’s correct that, unlike on most public platforms where you can publish essays, you should err on the side of giving more information rather than less. If you write well, and about interesting things, readers will feel more rewarded if there’s more of your writing.

Of course, this implies our next point —

V. Style: Be Better Than the Book

— which is that your review must absolutely be a delight to read.

There isn’t much to say. Just write good. Aim to make your review more enjoyable to read than the book you’re reviewing, since otherwise there isn’t much point in reading your review: people should just read the book instead.

(This does suggest that writing a review of a book that’s already fun to read is a risky proposition. I’m not sure how true this is.)

One attractive strategy to score high in the contest is to emulate Scott’s style. It is obvious that the people voting on the contest enjoy Astral Codex Ten’s usual mix of cleverness, microhumor, and awkwardly inserted parenthetical paragraphs. However, this has pitfalls. Copying someone’s style can come across as gauche. Some commenters have been known to complain about what they perceived as pastiches of the blog.

So I wouldn’t recommend deliberately doing it. But if you have a decent understanding of ACX and its audience, you may find that writing for the contest “shifts” your usual way of writing to fit the mold. That’s what happened to me, I think, and why my first review was described by a commenter as “injected … with as much ACX-bait as possible” and why my third one got mistaken for Scott’s own writing. None of that was on purpose, I swear!

VI. Dumb details

Some boring advice in closing, because no one told me this:

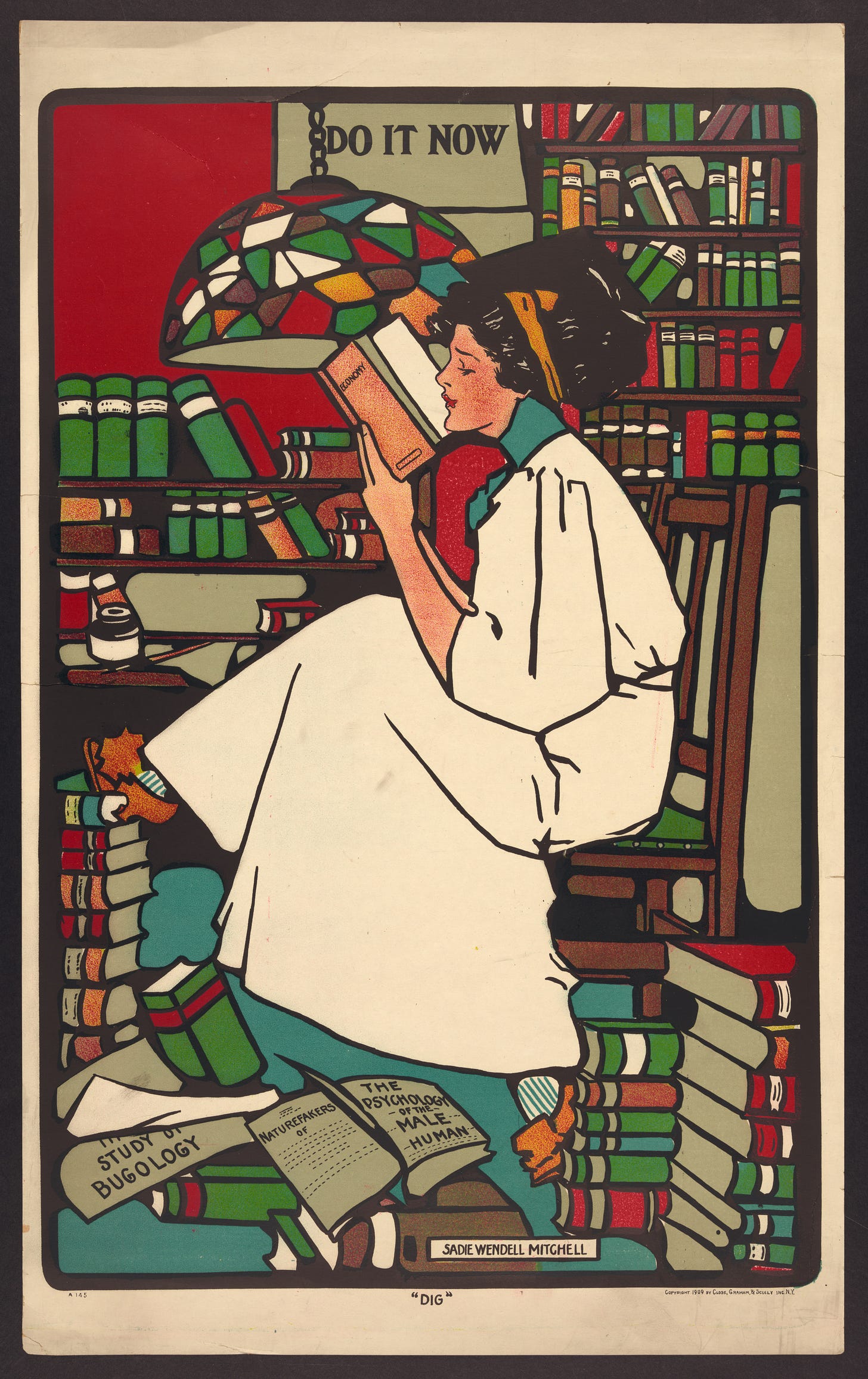

If you make it to the finals, your essay will be copy-pasted from a Google Doc to a Substack post without you being able to perform a quality check. Sometimes this causes problems. Certain images disappear for some reason. In my Making Nature review, Scott added an image that the text referred to because mine had vanished, and sadly I think it made a point (about the quality of the cover of the journal Cell) seem weaker. The review of The Castrato by friend-of-the-blog Roger’s Bacon somehow has most of its images duplicated with different sizes. Bizarre. So I recommend you test the Google-Doc-to-Substack conversion (which will be useful too if you post it on your own Substack). When I tried this with my Egypt post a few weeks ago I found that almost all images came out too big. Fixing it didn’t really matter because the review wasn’t selected — but I would have been quite annoyed at the overly wide pictures if it had been.

Also, if you want to use block quotes

like this,

just indent the relevant paragraphs in the Doc. And finally I have no idea how to make image captions in Google Docs that become image captions on Substack. If you figure it out let me know.

I’m glad the ACX contest exists, and not just because it allowed me to get some visibility for this blog twice. Like I said, it’s an interesting cultural artifact. ACX itself is a unique place, and the contest gives readers a chance to be part of it, while encouraging participants to learn something very in-depth. I think it’s worth trying even if you don’t think you’ll get anywhere near the finals.

The finalist entries for 2024 will be posted starting this Friday and, if it’s like last year, every week for the next fifteen weeks. If you happen to have written one of them, good luck! And if not, there’s always next year. (Well, maybe. Possibly Scott gets tired of it. In which case this essay would be completely useless. That’s fine.)

Some Handy Links, For Archive Purposes

2022 rules, final voting round, winners

2023 rules, initial voting round, finalists, final voting round, winners

2024 rules, initial voting round, finalists

Scott himself said:

Sure, feel free to write a review of an imaginary book. I think grabbing people's interest with this will be much harder than with a real book, but you can try if you want.

This year he said he’d do a bit of affirmative action to make sure there’s at least one finalist in some less represented categories, like fiction and poetry.

For most of the last days of the market in 2023, my review of Cities and the Wealth of Nations + The Question of Separatism was somehow the top predicted winner. That really got my hopes up for a while.

These topics correspond to these actual books, listed by contest year and then decreasing contest rank:

Progress and Poverty (first place in 2021)

Down and Out in Paris and London

On the Natural Faculties

Disunited Nations: Succeeding in a World Where No One Gets Along and The Dawn of Eurasia: On the Trail of the New World Order

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (first place in 2022)

1587: A Year of No Significance: The Ming Dynasty in Decline

The Castrato: Reflections on Natures and Kinds

The Future of Fusion Energy

The Internationalists: How a Radical Plan to Outlaw War Remade the World

The Educated Mind: How Cognitive Tools Shape Our Understanding (first place in 2023)

On the Marble Cliffs

Cities and the Wealth of Nations; The Question of Separatism (mine!)

Thanks for writing this! I completely agree with your comments, that to win a review needs to (a) clearly state the thesis of the book; (b) critique it, either with original thoughts or original data. I'd also add (c) have a clear structure and clear formatting - a surprising number of the reviews failed on this and were rather less enjoyable to read than they could have been. Write 10,000 words if you want, but don't write a wall of text.

For some cases, you also need (d) give some basic context to the book and justify why the book/topic is worth reviewing. The Rhyming Dictionary did this par excellence; the review of Asquith was a mostly well-written review which is nevertheless utterly incomprehensible even to most people with a strong interest in UK politics, let alone to the average ACX reader.

I would also agree that in order to be in the top running you need to choose a book which there is something to learn from in order to really get the high marks. There were a few books which tried to draw life lessons from a book which didn't really have anything to offer, or where the author is wildly unreliable (e.g. Dan Ariely, Peter Turchin). Perhaps the best review I read which didn't have life lessons, but which did have something of a critique, was The Hunt for Red October.

I read 61 of the reviews, including three of the eventual finalists, two honourable mentions, and yours. In my notes I gave yours 7/10 (I considered 8+ to be finalist-worthy); my notes suggest I thought it was well-written and generally pretty clear about what we do and don't know but that, since you quote a bunch of highly speculative and frankly ridiculous theories about Akhenaten, you could have done more to poor cold water on them. Plus, not a major thing but the neither the bust of Nefertiti nor King Tut's death mask is the most famous ancient Egyptian artefact (see https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=nefertiti%2Crosetta%2Ctutankhamun&year_start=1800&year_end=2019&corpus=en-2019&smoothing=3).

Good writeup. I entered the contest and struggled with it. In part because I just couldn't muster the effort to write a massive essay/"review" of a difficult book. I got bored trying to summarize the book for an audience of people that hadn't read it, and found it difficult to write anything original without giving a proper summary first.

It does seem to me that the choice of book is crucial. ACX is written by a psychiatrist, and many of its readers are programmers. So you want it to be something *adjacent* to those fields, but not directly *in* them. Too close and it will get nerd-swiped by people arguing with you, too far away and no one will care. It's kind of telling that no one has won for reviewing a classic programming book like "The Art of Computer Programming" and that he promised extra attention for fiction this year but still one of the few fiction books to make it in was... comic books.

I'm worried that what people want is a false confidence in some sort of crank theory. Like, the Georgian economics book review. Great essay! Really made me aware of Georgian economics for the first time and made it seem like a great idea. At the same time, I am keenly aware that I am *not* an economist, and that most mainstream economists don't really buy into Georgian economics all that much. So many the pros know something that I don't...? I hope this book review contest doesn't become a vehicle to push fringe views onto an audience that is smart but naiive.